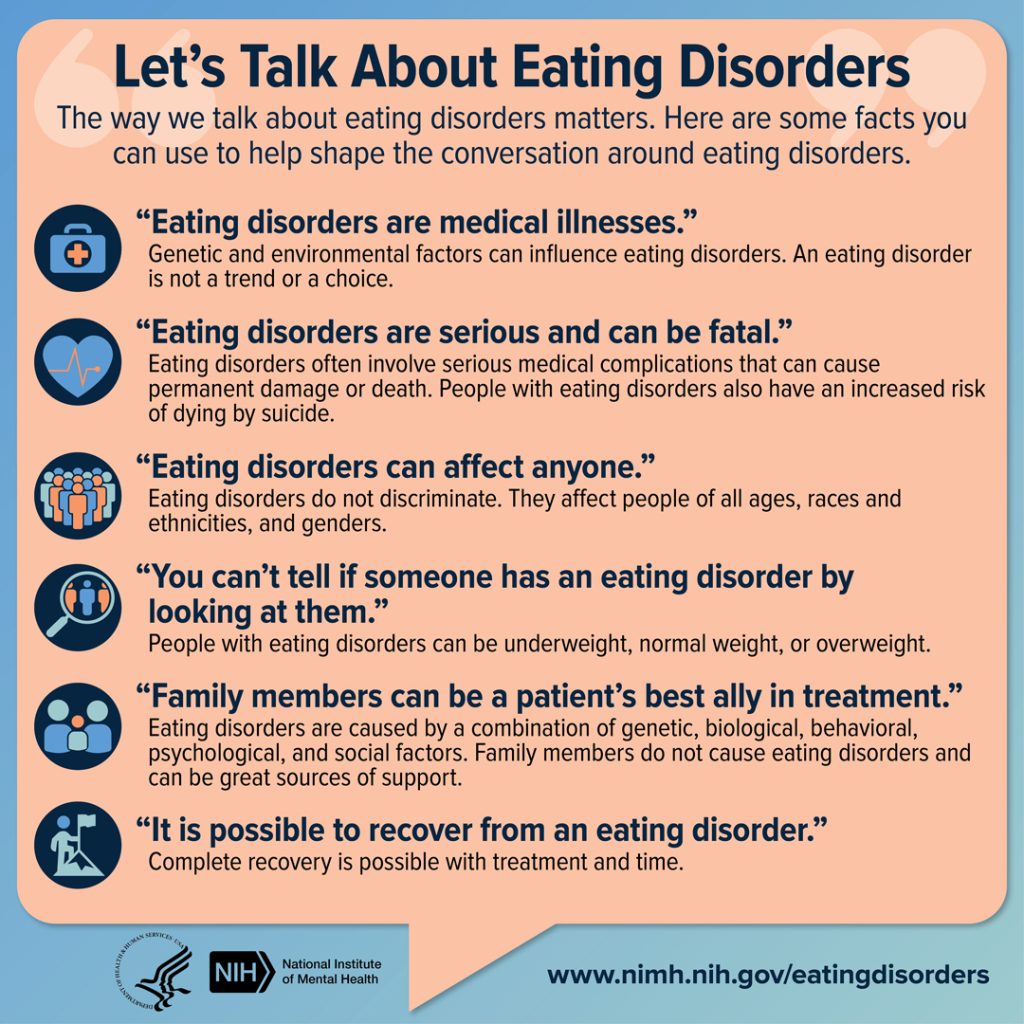

Eating disorders are serious medical illnesses, and the way we talk about them with others matters.[1] See Figure 13.1[2] with facts nurses can use to help shape the conversation around eating disorders.

Common Eating Disorders

Common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder.[3]

Anorexia Nervosa

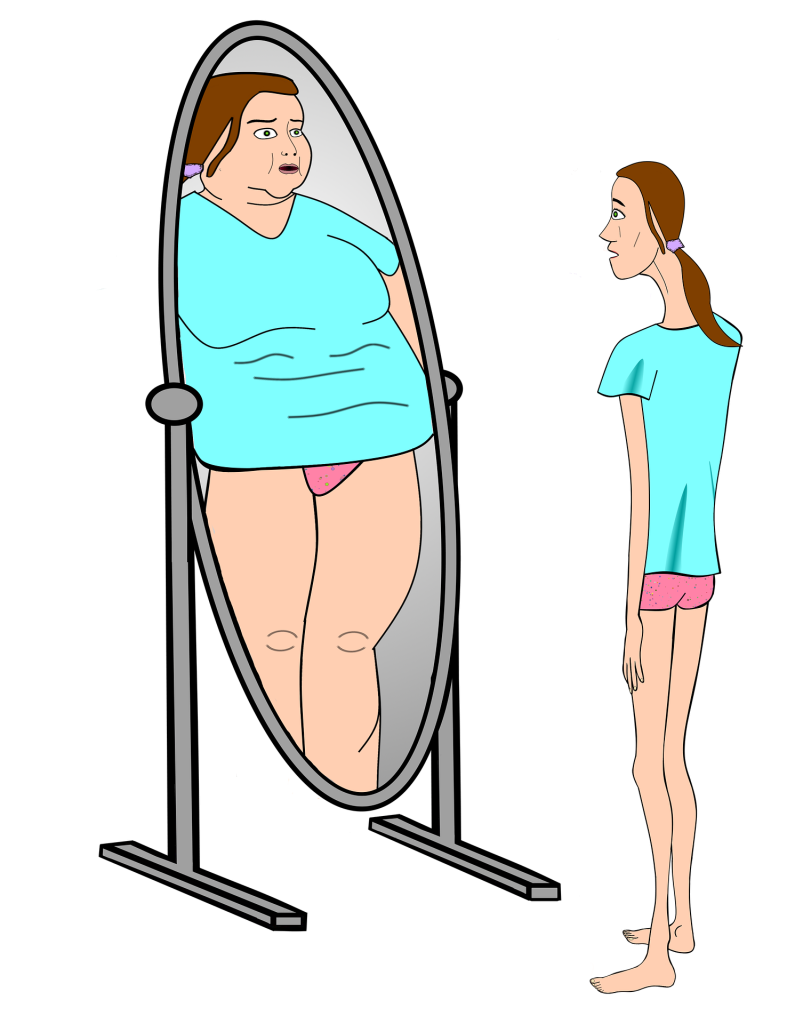

Anorexia nervosa is a condition where people avoid food, severely restrict food, or eat very small quantities of only certain foods. They have an intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat, even if they are significantly underweight. People with anorexia nervosa often have distorted body image and view themselves as overweight.[4] See Figure 13.2[5] for an illustration of how a person with anorexia nervosa may perceive themselves.

There are two subtypes of anorexia nervosa: restricting type and a binge eating/purging type. People with the restrictive subtype of anorexia nervosa severely limit the amount and type of food they consume or engage in excessive exercise. People with the binge-purge subtype have binge eating and/or purging episodes. Binge eating episodes refer to eating large amounts of food in a short period of time with a feeling of a loss of control. Purging episodes refer to eating large amounts of food in a short time followed by self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas to eliminate what was consumed.[6],[7]

Anorexia nervosa can be fatal due to medical complications associated with starvation. It has an extremely high mortality (death) rate compared with other mental health disorders. Young people between the ages of 15 and 24 with anorexia have 10 times the risk of dying compared to their same-aged peers. Males represent 25% of individuals with anorexia nervosa and are at a higher risk of dying because they are often diagnosed later than females.[8],[9]

Signs and symptoms of anorexia nervosa include the following[10]:

- Severely restricted eating

- Extreme thinness (also referred to as emaciation)

- A relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a healthy weight

- Intense fear of gaining weight

- Distorted body image where a person’s self-esteem is heavily influenced by their perception of their of body weight and shape

- Denial of the seriousness of low body weight

Other signs may develop over time, including these issues[11]:

- Thinning of the bones (i.e., osteopenia or osteoporosis)

- Anemia

- Muscle wasting and weakness

- Brittle hair and nails

- Dry and yellowish skin

- Growth of fine hair all over the body (lanugo)

- Severe constipation

- Low blood pressure

- Slowed breathing and pulse

- Drop in internal body temperature, causing the person to feel cold all the time

- Lethargy, sluggishness, or feeling tired all the time

- Infertility

- Damage to the structure and function of the heart

- Brain damage

- Multiorgan failure

See the following box for criteria used to diagnose anorexia nervosa according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Disorders (DSM-5).

DSM-5 Criteria for Anorexia Nervosa[12]

- Restrictions of energy intake relative to requirements, leading to significantly low body weight in the context of age, sex, developmental trajectory, and physical health. Significantly low weight is defined as weight less than minimally normal, or in children and adolescents, less than that minimally expected.

- Intense fear of gaining weight or becoming fat or persistent behavior that interferes with weight gain, even though already at a significantly low weight.

- Disturbance in the way in which one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight.

The type is specified as follows:

- Restricting type: Weight loss is accomplished primarily through dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise. During the last three months, the individual has not engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behavior.

- Binge eating/purging type: During the last three months, the individual has engaged in recurrent episodes of binge eating or purging behavior (i.e., self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or enemas).

Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is a condition where people have recurrent and frequent episodes of binge eating (i.e., eating unusually large amounts of food in a short amount of time while also feeling a lack of control over these episodes). Binge eating is followed by behaviors used to eliminate the excess food such as forced vomiting, excessive use of laxatives or diuretics, fasting, excessive exercise, or a combination of these behaviors. People with bulimia nervosa may be slightly underweight, normal weight, or overweight.[13]

Signs and symptoms of bulimia nervosa include the following[14]:

- Chronically inflamed and sore throat

- Swollen salivary glands in the neck and jaw area

- Worn tooth enamel and increasingly sensitive and decaying teeth as a result of exposure to stomach acid

- Acid reflux disorder and other gastrointestinal problems

- Intestinal distress and irritation from laxative abuse

- Severe dehydration from purging of fluids

- Electrolyte imbalance (sodium, calcium, potassium, and other minerals) that can lead to dysrhythmias and cardiac arrest

See the following box for DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing bulimia nervosa.

DSM-5 Criteria for Bulimia Nervosa[15]

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating. A binge eating episode is characterized by both of the following:

- Eating in a discrete period of time (e.g., within any two-hour period) an amount of food that is definitely larger than what most individuals would eat in a similar period of time under similar circumstances.

- A sense of lack of control overeating during the episode (i.e., feeling that one cannot stop eating or control what or how much one is eating).

- Recurrent inappropriate compensatory behavior to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting; misuse of laxatives, diuretics, or other medications; fasting; or excessive exercise.

- The binge eating and inappropriate compensatory behaviors both occur, on average, at least once a week for three months.

- Self-evaluation is unduly influenced by body shape and weight.

- The disturbance does not occur exclusively during episodes of anorexia nervosa.

Binge Eating Disorder

Binge eating disorder is the most common eating disorder in the United States.[16]Binge eating disorder is a condition where people lose control over their eating and have recurring episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food. However, unlike bulimia nervosa, periods of binge eating are not followed by purging, excessive exercise, or fasting. As a result, people with binge eating disorder often are overweight or obese.[17]

These are the signs and symptoms of a binge eating disorder[18]:

- Eating unusually large amounts of food in a specific amount of time, such as a two-hour period

- Eating even when feeling full or not hungry

- Eating at a fast pace

- Eating until uncomfortably full

- Eating alone or in secret to avoid embarrassment

- Feeling distressed, ashamed, or guilty about eating

- Frequent dieting, possibly without weight loss

See the DSM-5 criteria for diagnosing binge eating disorder in the following box.

DSM-5 Criteria for Binge Eating Disorder[19]

- Recurrent episodes of binge eating.

- The binge eating episodes are associated with three (or more) of the following:

- Eating much more rapidly than normal.

- Eating until feeling uncomfortably full.

- Eating large amounts of food when not feeling physically hungry.

- Eating alone because of being embarrassed by how much one is eating.

- Feeling disgusted with oneself, depressed, or very guilty afterward.

- Marked distress regarding binge eating is present.

- The binge eating occurs, on average, at least once a week for three months.

- The binge eating is not associated with the recurrent use of inappropriate compensatory behavior, such as in bulimia nervosa, and does not occur exclusively during the course of bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa.

Other Eating Disorders

Pica is another type of eating disorder in which an individual repeatedly eats things that are not considered food and have no nutritional value, such as paper, dirt, soap, hair, glue, or chalk. Individuals with pica do not usually have an aversion to food, and ingested items vary with age. The behavior is inappropriate to the developmental level of the individual and is not part of a culturally supported practice. A person diagnosed with pica is at risk for potential intestinal blockages or toxic effects of substances consumed (such as lead in paint chips). Treatment for pica involves testing for nutritional deficiencies and addressing them if needed. Behavioral interventions used to treat pica may include redirecting the individual from the nonfood items and rewarding them for setting aside or avoiding nonfood items.[20]

Avoidant restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is a condition where individuals limit the amount or type of food eaten. Unlike anorexia nervosa, people with ARFID do not have a distorted body image or extreme fear of gaining weight. ARFID is most common in middle childhood and usually has an earlier onset than other eating disorders. Many children go through phases of picky eating, but a child with ARFID does not eat enough calories to grow and develop properly, and an adult with ARFID does not eat enough calories to maintain basic body function.[21]

Signs and symptoms of ARFID include the following[22]:

- Dramatic restriction of types or amount of food eaten

- Lack of appetite or interest in food

- Dramatic weight loss

- Upset stomach, abdominal pain, or other gastrointestinal issues with no other known cause

- Limited range of preferred foods that becomes even more limited (i.e., “picky eating” that gets progressively worse)

ARFID does not include food restriction related to lack of availability of food; dieting; cultural practices, such as religious fasting; or developmentally normal behaviors, such as toddlers who are picky eaters. Food avoidance or restriction commonly develops in infancy or early childhood and may continue in adulthood, but it can start at any age. Regardless of the age of the person affected, ARFID can impact families, causing increased stress at mealtimes and in other social eating situations. Treatment for ARFID involves an individualized plan and may involve several specialists, including a mental health professional and a registered dietician.

Body Mass Index

Body mass index (BMI) is a person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. BMI is an easy screening method to determine if an individual’s weight is classified as underweight, healthy weight, overweight, or obese. However, it is important to remember that BMI is a screening method and does not take into account muscle mass, bone density, overall body composition, racial, and sex differences.[23] See Table 13.2a for adult weight status according to BMI ranges.

Table 13.2a Adult Weight Status by BMI[24]

| BMI | Weight Status |

|---|---|

| Below 18.5 | Underweight |

| 18.5 – 24.9 | Healthy Weight |

| 25.0 – 29.9 | Overweight |

| 30.0 or higher | Obese |

For children and teens, the interpretation of BMI depends upon their age and sex. After BMI is calculated for children and teens, it is expressed as a percentile obtained from either a percentile calculator or growth chart. See categories of weight status based on BMI percentiles in Table 13.2b. Links to calculators and growth charts are provided in the following box.

Table 13.2b Child or Adolescent Weight Status by BMI Percentile[25]

| BMI Percentile | Weight Status |

|---|---|

| Less than 5th Percentile | Underweight |

| 5th Percentile to Less Than 85th Percentile | Healthy Weight |

| 85th Percentile to Less Than 95th Percentile | Overweight |

| 95th Percentile or Higher | Obese |

Calculating BMI

The CDC’s Adult BMI Calculator conveniently calculates a person’s BMI based on their height and weight. The following formulas can also be used to calculate a person’s BMI[26]:

- weight (kg) / [height (m)]2 or

- weight (lb) / [height (in)]2 x 703

The CDC’s BMI Percentile Calculator for Children and Adolescents conveniently calculates a child’s or adolescent’s BMI percentile based on their height, weight, gender, and age. Otherwise, gender growth charts are used to determine BMI percentiles and then their weight status is determined using the appropriate table below:

Risk Factors

The exact cause of eating disorders is not fully understood, but research suggests that a combination of genetic, biological, behavioral, psychological, and cultural factors can increase a person’s risk. Eating disorders are hereditary. Researchers are working to identify DNA variations that are linked to the increased risk of developing eating disorders. Brain imaging studies are also providing a better understanding of eating disorders. For example, researchers have found differences in patterns of brain activity in women with eating disorders in comparison to healthy women. This kind of research can help guide the development of new means of diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders.[27]

Although genetics increases the risk for developing eating disorders, the individual’s environment plays a significant role. Onset can occur at nearly any point in the life span, but eating disorders commonly start in adolescence and young adulthood when there can be exceptional pressure from peers, social media, advertisements, etc., to diet or lose weight. For those genetically vulnerable to eating disorders, initial weight loss may reinforce a reward feedback mechanism and establish a maladaptive eating behavior pattern. Physiological and sensorial changes result in alterations in hunger and satiety, gastrointestinal motility, and decision-making around food and eating.

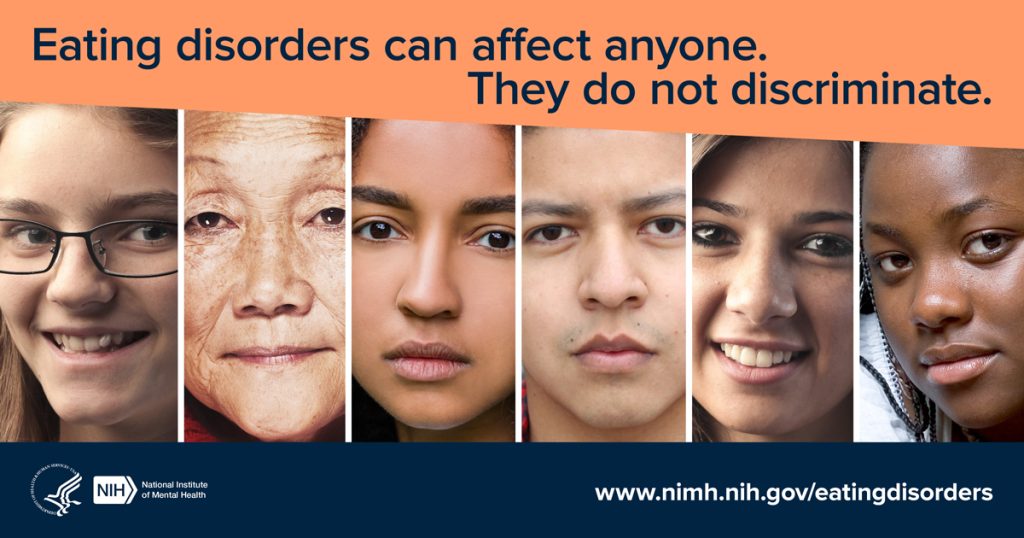

As you consider the genetic, environmental, and social influences of eating disorders, recognize that a combination of these factors can affect the severity and presenting characteristics for each client. Additionally, although eating disorders are commonly thought of as affecting young women, it can affect people of all genders, ages, races/ethnicities, body weights, and socioeconomic statuses. People with body weight or BMI within normal ranges can have eating disorder behaviors. See Figure 13.3[28] for an illustration of its diverse impact. Some individuals are mildly affected throughout their lives but then triggered by a significant physical or emotional life event that manifests clinical worsening.

Cultural Considerations

Cultural beliefs impact self-concept and satisfaction with body size. Anorexia nervosa is associated with cultures that value thinness. Furthermore, studies indicate that social media significantly influences these beliefs. For example, one study found that participants with higher use of social media had significantly greater odds of having eating concerns.[29] See Figure 13.4[30] for an image of an extremely underweight fashion model in a culture that values thinness.

Black and Hispanic teenagers are more likely to suffer from bulimia nervosa. Additional considerations are the influences of some sports cultures on athletes where weight is a consideration, such as in wrestling, gymnastics, figure skating, and body building. [31]

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- “2020_eatingdisorderinfographics_final.jpg” by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health is in the Public Domain ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- “maxpixel.net/Bulimia-Anorexia-Nervosa-Skimmed-Delusional-4049661.png” by unknown author is licensed under CC0. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- National Eating Disorders Association. (n.d.). Statistics and research on eating disorders. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics-research-eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2021, March). What are eating disorders? https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- Nordqvist, C. (2022, January 19). Why BMI is inaccurate and misleading. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/265215 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, August 27). About adult BMI. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#Interpreted ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, August 27). About adult BMI. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#Interpreted ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, August 27). About adult BMI. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/adult_bmi/index.html#Interpreted ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2021, December). Eating disorders. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/eating-disorders ↵

- “eating-disorders-everyone-sm.jpg” by U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health is in the Public Domain ↵

- Sidani, J. E., Shensa, A., Hoffman, B., Hanmer, J., & Primack, B. A. (2016). The association between social media use and eating concerns among us young adults. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 116(8), 1465-1472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2016.03.021 ↵

- “7991065935_8f05b38f46_k” by Farrukh is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0. ↵

- National Eating Disorders Association. Statistics and research on eating disorders. https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/statistics-research-eating-disorders ↵

A condition where people avoid food, severely restrict food, or eat very small quantities of only certain foods.

Eating large amounts of food in a short period of time with a feeling of a loss of control.

Eating large amounts of food in a short time followed by vomiting or using laxatives or diuretics to eliminate what was consumed.

Extreme thinness.

Growth of fine hair all over the body.

A condition where people have recurrent and frequent episodes of binge eating.

A condition where people lose control over their eating and have recurring episodes of eating unusually large amounts of food.

Type of eating disorder in which an individual repeatedly eats things that are not considered food and have no nutritional value, such as paper, dirt, soap, hair, glue, or chalk.

A condition where individuals limit the amount or type of food eaten.

A person’s weight in kilograms divided by the square of height in meters.