Substance-Related Disorders

Prolonged, repeated misuse of substances can produce changes to the brain that can lead to a substance use disorder. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), substance use disorder (SUD) is an illness caused by repeated misuse of substances such as alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants (amphetamines, cocaine, and other stimulants), and tobacco. All of these substances taken in excess have a common effect of directly activating the brain reward system and producing such an intense activation of the reward system that normal life activities may be neglected. Nonsubstance related disorders such as gambling disorder activate the same reward system in the brain.[1]

Substance use disorders are diagnosed based on cognitive, behavioral, and psychological symptoms. See the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria used for SUD in the following box. SUD can range from mild to severe and from temporary to chronic.[2]

DSM-5 Criteria for Substance Abuse Disorder

SUD diagnosis requires the presence of two or more of the following criteria in a 12-month period[3]:

- The substance is often taken in larger amounts or over a longer period than intended.

- There is a persistent desire or unsuccessful efforts to cut down or control substance use.

- A great deal of time is spent in activities necessary to obtain the substance, use the substance, or recover from its effects.

- There is a craving, or a strong desire or urge, to use the substance.

- There is recurrent substance use resulting in a failure to fulfill major role obligations at work, school, or home.

- There is continued substance use despite having persistent or recurrent social or interpersonal problems caused by or exacerbated by the effects of the substance.

- Important social, occupational, or recreational activities are given up or reduced because of substance use.

- There is recurrent substance use in situations in which it is physically hazardous.

- Substance use is continued despite knowledge of having a persistent or recurrent physical or psychological problem that is likely to have been caused or exacerbated by the substance.

- Tolerance develops to the substance, as defined by:

- A need for markedly increased amounts of the substance to achieve intoxication or the desired effect.

- There is a markedly diminished effect with continued use of the same amount of the substance.

- Withdrawal symptoms occur when substance use is cut back or stopped following a period of prolonged use.

The disorder is classified as mild, moderate, or severe. Individuals exhibiting two or three symptoms are considered to have a “mild” disorder, four or five symptoms constitute a “moderate” disorder, and six or more symptoms are considered a “severe” substance use disorder.

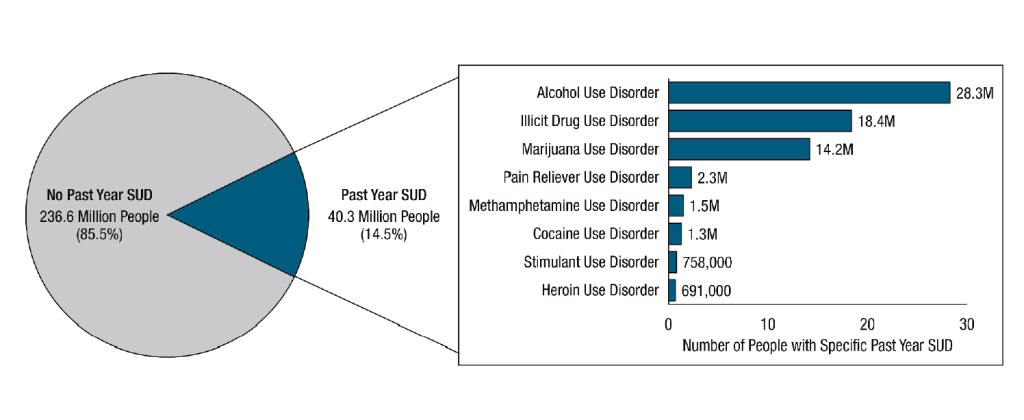

Millions of Americans are diagnosed with SUD. See Figure 14.6[4] for a graphic of the number of people aged 12 and older with a substance use disorder in 2020.

SUD often develops gradually over time due to repeated misuse of a substance, causing changes in brain areas that control reward, stress, and executive functions like decision-making and self-control. Multiple factors influence whether a person will develop a substance use disorder such as the substance itself; the genetic vulnerability of the user; and the amount, frequency, and duration of the misuse.

Severe substance use disorders are commonly referred to as addictions. Addiction is associated with compulsive or uncontrolled use of one or more substances. Addiction is a chronic illness that has the potential for both relapse and recovery. Relapse refers to the return to substance use after a significant period of abstinence. Recovery is a process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential. Although abstinence from substance misuse is a primary feature of a recovery lifestyle, it is not the only healthy feature.[5] The chronic nature of addiction means that some individuals may relapse after an attempt at abstinence, which can be a normal part of the recovery process. Relapse does not mean treatment failure. Relapse rates for substance use are similar to rates for adherence to therapies for other chronic medical illnesses. There are a variety of medications that can be prescribed to assist with relapse prevention.[6]

Individuals with severe substance use disorders can overcome their disorder with effective treatment and regain health and social function, referred to as remission. When positive changes and values become part of a voluntarily adopted lifestyle, this is referred to as “being in recovery.”[7] Among the 29.2 million adults in 2020 who have ever had a substance use problem, 72.5 percent considered themselves to be in recovery.[8]

Many individuals seeking care in health care settings, such as primary care, obstetrics and gynecology, emergency departments, and medical-surgical units, have undiagnosed substance use disorders. Recognition and early treatment of substance use disorders can improve their health outcomes and reduce overall health care costs.[9]

Substance Use Disorder in Nurses

Health care professionals are not immune to developing SUD. SUD is a chronic illness that can affect anyone regardless of age, occupation, economic circumstances, ethnic background, or gender. The National Council of State Boards of Nursing (NCSBN) created a brochure called A Nurse’s Guide to Substance Use Disorder in Nursing. This brochure states that many nurses with substance use disorder (SUD) are unidentified, untreated, and may continue to practice when their impairment may endanger the lives of their clients. Because of the potential safety hazards to clients, it is a nurse’s legal and ethical responsibility to report a colleague’s suspected SUD to their manager or supervisor. It can be hard to differentiate between the subtle signs of SUD and stress-related behaviors, but three significant signs include behavioral changes, physical signs, and drug diversion.[10]

Behavioral changes include decreased job performance, absences from the unit for extended periods, frequent trips to the bathroom, arriving late or leaving early, and making an excessive number of mistakes including medication errors.[11]

Physical signs include subtle changes in appearance that may escalate over time; increasing isolation from colleagues; inappropriate verbal or emotional responses; and diminished alertness, confusion, or memory lapses. Signs of diversion include frequent discrepancies in opioid counts, unusual amounts of opioid wastage, numerous corrections of medication records, frequent reports of ineffective pain relief from clients, offers to medicate coworkers’ patients for pain, and altered verbal or phone medication orders.[12]

Drug diversion occurs when medication is redirected from its intended destination for personal use, sale, or distribution to others. It includes drug theft, use, or tampering (adulteration or substitution). Drug diversion is a felony that can result in a nurse’s criminal prosecution and loss of license.[13]

The earlier that a nurse is diagnosed with SUD and treatment is initiated, the sooner that client safety is protected and the better the chances for the nurse to recover and return to work. In most states, a nurse diagnosed with a SUD enters a nondisciplinary program designed by the Board of Nursing for treatment and recovery services. When a colleague treated for an SUD returns to work, nurses should create a supportive environment that encourages their continued recovery.[14]

View the NCSBN PDF pamphlet A Nurse’s Guide to Substance Use Disorder in Nursing.

Nonsubstance-Related Disorders

Nonsubstance-related disorders are excessive behaviors related to gambling, viewing pornography, compulsive sexual activity, Internet gaming, overeating, shopping, overexercising, and overusing mobile phone technologies. These behaviors are thought to stimulate the same addiction centers of the brain as addictive substances. However, gambling disorder is the only nonsubstance use disorder with diagnostic criteria listed in the DSM-5. See the DSM-5 criteria for the diagnosis of a gambling disorder in the following box. Additional research is being performed to determine the criteria for diagnosing other nonsubstance-related disorders.[15]

DSM-5 Criteria for Gambling Disorder[16]

Gambling disorder is defined as persistent and recurrent problematic gambling behavior leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as indicated by four or more of the following criteria in a 12-month period. Additionally, the gambling behavior is not better explained by a manic episode.

- Needs to gamble with increasing amounts of money to achieve the desired excitement

- Is restless or irritable when attempting to cut down or stop gambling

- Has made repeated unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back, or stop gambling

- Is often preoccupied with gambling (e.g., persistent thoughts of reliving past gambling experiences, planning the next venture, or thinking of ways to get money with which to gamble)

- Often gambles when feeling distressed (e.g., helpless, guilty, anxious, or depressed)

- After losing money gambling, often returns another day to get even (otherwise known as “chasing one’s losses”)

- Lies to conceal the extent of involvement with gambling

- Has jeopardized or lost a significant relationship, job, or educational or career opportunity because of gambling

- Relies on others to provide money to relieve desperate financial situation caused by gambling

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- This image is a derivative of “People Aged 12 or Older with a Past Year Substance Use Disorder (SUD); 2020” table by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (HHS Publication No. PEP21-07-01-003, NSDUH Series H-56). Rockville, MD: Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Used under Fair Use. Retrieved from https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-nsduh-annual-national-report ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2022). Drugs, brains, and behavior: The science of addiction treatment and recovery. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugs-brains-behavior-science-addiction/treatment-recovery ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2021). Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 national survey on drug use and health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality, Substance Abuse, & Mental Health Services Administration. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/ ↵

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, & Office of the Surgeon General. (2016). Facing addiction in America: The surgeon general's report on alcohol, drugs, and health. United States Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK424857/ ↵

- NCSBSN. (2018). A nurse’s guide to substance use disorder in nursing [Brochure]. https://www.ncsbn.org/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- NCSBSN. (2018). A nurse’s guide to substance use disorder in nursing [Brochure]. https://www.ncsbn.org/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- NCSBSN. (2018). A nurse’s guide to substance use disorder in nursing [Brochure]. https://www.ncsbn.org/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- Nyhus, J. (2021). Drug diversion in healthcare. American Nurse. https://www.myamericannurse.com/drug-diversion-in-healthcare/ ↵

- NCSBSN. (2018). A nurse’s guide to substance use disorder in nursing [Brochure]. https://www.ncsbn.org/SUD_Brochure_2014.pdf ↵

- National Institute on Drug Abuse, & National Institutes of Health. (2019, May). Methamphetamine drugfacts. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/methamphetamine ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

An illness caused by repeated misuse of substances such as alcohol, caffeine, cannabis, hallucinogens, inhalants, opioids, sedatives, hypnotics, anxiolytics, stimulants (amphetamines, cocaine, and other stimulants), and tobacco.

Associated with compulsive or uncontrolled use of one or more substances.

The return to substance use after a significant period of abstinence.

A process of change through which individuals improve their health and wellness, live a self-directed life, and strive to reach their full potential.

Individuals with severe substance use disorders can overcome their disorder with effective treatment and regain health and social function.

When medication is redirected from its intended destination for personal use, sale, or distribution to others.

Excessive behaviors related to gambling, viewing pornography, compulsive sexual activity, Internet gaming, overeating, shopping, overexercising, and overusing mobile phone technologies.