Working with children and adolescents is very different from working with adults. Young people are often reluctant participants who have been brought for care they did not seek on their own. Additionally, their communication skills are limited based on their developmental stage. In addition to gathering information from the child, information must also be obtained from the parent or caregiver.[1]

The first step to successful care is to create a therapeutic nurse-client relationship. A therapeutic alliance can typically be created if the young person feels noticed, heard, and appreciated. It is often helpful to start the conversation with a relatively neutral question like, “Your mom said that you go to ____ school. What is that school like?” School, friends, family, and favorite activities are low-stress conversation starters. For a very young child, a conversation starter could be a simple observation like what they are wearing. For example, “I see you are wearing blue tennis shoes; did you pick those out yourself?”[2]

For young people who seem reluctant to start talking, it may be helpful to describe something you saw that shows you have been paying attention to them. For example, “It looked as though it was hard for you to sit and do nothing while your dad and I were talking. Am I right about that?”[3]

When caring for adolescents, it is helpful to gather data from the parent or caregiver, and then ask to speak with the adolescent alone. Reinforce that the conversation is “conditionally confidential” and invite the adolescent to sit alone with you to talk. A 1:1 conversation with an adolescent typically creates a better therapeutic alliance with more honest answers obtained.[4]

A more subtle strategy to build a therapeutic-nurse relationship with children and adolescents is to shape how you speak so you are perceived as a responsive problem-solving partner rather than an authority figure who will judge them. Building a therapeutic nurse-client relationship with a young person should lead to learning their true chief complaint because the chief complaint of an adolescent may be different from their parents’ complaints.[5] Furthermore, goal setting and treatment plans will be more effective when the adolescent’s concerns are addressed.

Privacy, Confidentiality, and Mandatory Reporting

Confidentiality should be discussed with the adolescent client and their parent/guardian before beginning an assessment or related conversations, and circumstances should be defined for when confidentiality is “conditional” for children and adolescents. State laws determine what information is considered confidential and what requires reporting to law enforcement or Child Protective Services. Examples of what must be reported to law enforcement include child abuse, gunshot or stabbing wounds, sexually transmitted infections, abortions, suicidal ideation, and homicidal ideation. Some state laws make it optional for clinicians to inform parents/guardians if their child is seeking services related to sexual health care, substance abuse, or mental health care. Nurses should be aware of the state laws affecting the confidentiality of child and adolescent care in the state in which they are practicing.[6]

Although it is important for nurses to respect adolescent clients’ privacy and confidentiality, it is also important to encourage the adolescent to talk with their parents/guardians about personal issues that affect their health even if they feel uncomfortable doing so. Parent/guardian support can help ensure the adolescent’s health needs are met.[7]

Research your state’s laws regarding adolescent clients’ rights.

Here is a link to Wisconsin Department of Health Services’ Client Rights for Minors.

Assessment

Parents and caregivers typically bring a child or adolescent in for mental health evaluation due to common concerns, such as the following:

- Poor academic performance

- Developmental delays

- Disruptive or aggressive behavior

- Withdrawn or sad mood

- Irritable or labile mood

- Anxious or avoidant behavior

- Recurrent and excessive physical complaints

- Sleep problems

- Self-harm and suicidality

- Substance abuse

- Disturbed eating

Poor academic performance is a common concern. Keep in mind that assessing a child’s/adolescent’s ability to function in school is like assessing an adult’s ability to function at work. Many factors can affect a young person’s performance at school, such as their ability and effort, the classroom environment, life distractions, or a mental health disorder.

Recall that ability may be impacted by hearing or visual impairments, learning disorders, or cognitive impairments. The nurse may assist with performing vision or hearing tests or providing a developmental rating scale. Signs of abuse, neglect, or bullying are important for the nurse to observe and report. Read more about abuse and neglect in the “Trauma, Abuse, and Violence” chapter.

Psychosocial Assessment and Mental Status Examination

Specific signs and symptoms of a mental health disorder should be assessed as part of the “health history” component of a comprehensive nursing assessment. While asking questions about specific symptoms and obtaining a health history, the nurse should also be simultaneously performing a mental status examination. The mental status examination includes these items:

- Appearance and General Behavior

- Speech

- Motor Activity

- Affect and Mood

- Thoughts and Perceptions

- Attitude and Insight

- Cognitive Abilities

Review details of a mental status examination in the “Application of the Nursing Process in Mental Health Care” chapter.

Family Dynamics

Family dynamics refers to the patterns of interactions among family members, their roles and relationships, and the various factors that shape their interactions. Because family members typically rely on each other for emotional, physical, and economic support, they are one of the primary sources of relationship security or stress. Secure and supportive family relationships provide love, advice, and care, whereas stressful family relationships may include frequent arguments, critical feedback, and unreasonable demands.[8]

Interpersonal interactions among family members have lasting impacts and influence the development and well-being of children. Unhealthy family dynamics can cause children to experience trauma and stress as they grow up, known as adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Conflict between parents and adolescents is associated with adolescent aggression, whereas mutuality (cohesion and warmth) is shown to be a protective factor against aggressive behavior.[9]

Effectively assessing and addressing a client’s family dynamics and its role in a child’s or adolescent’s mental health disorder requires an interprofessional team of health professionals, including nurses, physicians, social workers, and therapists. Nurses are in a unique position to observe interaction patterns, assess family relationships, and attend to family concerns in clinical settings because they are in frequent contact with family members. Collaboration among interprofessional team members promotes family-centered care and provides clients and families with the necessary resources to develop and maintain healthy family dynamics.[10]

Life Span Considerations

Review theories of development across the life span in the “Application of the Nursing Process in Mental Health Care” chapter.

Adolescence is a time of exploration regarding gender identity, gender roles, and sexual orientation. As previously discussed, assuring conditional confidentiality is the first step in establishing basic trust and a therapeutic nurse-client relationship with an adolescent patient. Most adolescents require privacy to talk candidly about their gender identity and sexuality, so parents/guardians should be asked to leave the examination room at some point during the visit.[11]

Cultural Considerations

The Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI) is a structured tool in the DSM-5 used to assess the influence of culture on a client’s experience of distress. See the following box for an adapted version of the CFI tool for children and adolescents.[12]

Adapted Cultural Formulation Interview for Children and Adolescents[13]

- Suggested introduction to the child or adolescent: We have talked about the concerns of your family. Now I would like to know how you are feeling about being ___ years old.

- Feelings of age appropriateness in different settings: Do you feel you are like other people your age? In what way? Do you sometimes feel different from other people your age? In what way?

- If they acknowledge sometimes feeling different: Does this feeling of being different happen more at home, at school, at work, and/or some other place? Do you feel your family is different from other families? Does your name have special meaning for you? Is there something special about you that you like or are proud of?

- Age-related stressors and supports: What do you like about being at home? At school? With friends? What don’t you like at home? At school? With friends? Who is there to support you when you feel you need it? At home? At school? Among your friends?

- Age-related expectations: What do your parents or grandparents expect from a person your age in terms of chores, schoolwork, play, or religion? What do your teachers expect from a person your age? What do other people your age expect from a person your age? (If they have siblings, what do your siblings expect from a person your age?)

- Transition to adulthood (for adolescents): Are there any important celebrations or events in your community that recognize reaching a certain age or growing up? When is a youth considered ready to become an adult in your family or community? What is good about becoming an adult in your family? In school? In your community? How do you feel about “growing up”? In what ways are your life and responsibilities different from your parents’ life and responsibilities?

Diagnoses

Health care professionals use the guidelines in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) to diagnose mental health disorders in children.[14]

Nurses customize nursing diagnoses based on the child’s or adolescent’s response to mental health disorders, their current signs and symptoms, and the effects on their and their family’s functioning. Here are common nursing diagnoses related to childhood and adolescent disorders[15],[16],[17]:

- Anxiety

- Chronic Low Self-Esteem

- Disabled Family Coping

- Impaired Social Interactions

- Ineffective Impulse Control

- Risk for Delayed Development

- Risk-prone Health Behavior

- Risk for Impaired Parenting

- Risk for Spiritual Distress

Outcome Identification

Broad goals focus on reducing symptoms of mental health disorders that interfere with the child’s or adolescent’s daily functioning and quality of life. SMART outcomes stand for outcomes that are specific, measurable, achievable, and realistic with a timeline indicated. They are customized according to each client’s diagnoses and needs. Read more about SMART outcomes in the “Application of the Nursing Process in Mental Health Care” chapter.

For example, a SMART outcome for a child diagnosed with attention deficit disorder is, “The client will demonstrate reduced impulsive behaviors, as reported by parents and their teachers, within two weeks of initiating stimulant medication.”

Planning Interventions

A public health approach to children’s mental health includes promoting mental health for all children, providing preventative measures for children at risk, and implementing interventions.[18]

Prevention

It is not known why some children develop disruptive behavior disorders, but children are at greater risk if they are exposed to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Toxic stress from ACEs can alter brain development and affect how the body responds to stress. ACEs are linked to chronic health problems, mental illness, and substance abuse. Children with three or more reported ACEs, compared to children with zero reported ACEs, had higher prevalence of one or more mental, emotional, or behavioral disorders (36.3% versus 11.0%).[19]

Preventing ACEs can help children thrive into adulthood by lowering their risk for chronic health problems and substance abuse, improve their education and employment potential, and stop ACEs from being passed from one generation to the next.[20]

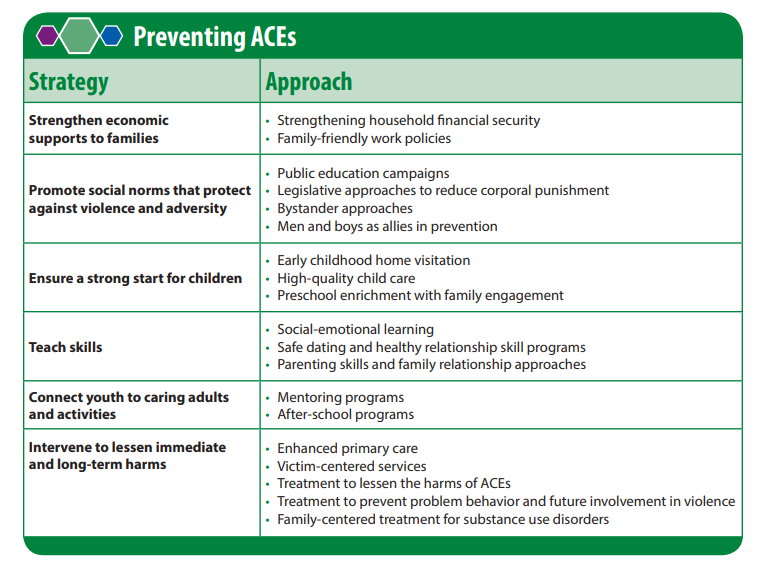

Raising awareness about ACEs can help reduce stigma around seeking help for parenting challenges, substance misuse, depression, or suicidal thoughts. Community solutions focus on promoting safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments where children live, learn, and play. In addition to raising awareness and participating in community solutions, nurses should recognize ACE risk factors and refer clients and their families for effective services and support. See Figure 12.8[21] regarding strategies to prevent ACEs.

Read Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences PDF by the CDC with evidence-supporting interventions.

Planned Interventions

The following interventions can be planned by nurses for children and adolescents in a variety of settings, including inpatient, outpatient, day treatment, outreach programs in schools, and home visits.[22]

Behavioral Interventions

Behavioral interventions reward desired behaviors to reduce maladaptive coping behaviors. Most child and adolescent treatment settings use structured programs to motivate and reward age-appropriate behaviors. For example, the point or star system may be used where the child receives points or stars for desired behaviors, and then specific privileges are awarded based on the points or stars earned each day.[23]

Read more about interprofessional behavioral interventions for the child, parents/caregivers, and teachers in the “Psychological Therapies and Behavioral Interventions” section.

Play Therapy

Children develop physically, intellectually, emotionally, and socially through play. Play therapy encourages children to express feelings such as anxiety, self-doubt, and fear through their natural play. It also allows them to work through painful or traumatic memories. For example, nurses often use dolls or other toys to help children work through feelings of fear prior to a medical procedure.[24] See Figure 12.9[25] for an image of children with special needs playing at a school for autism.

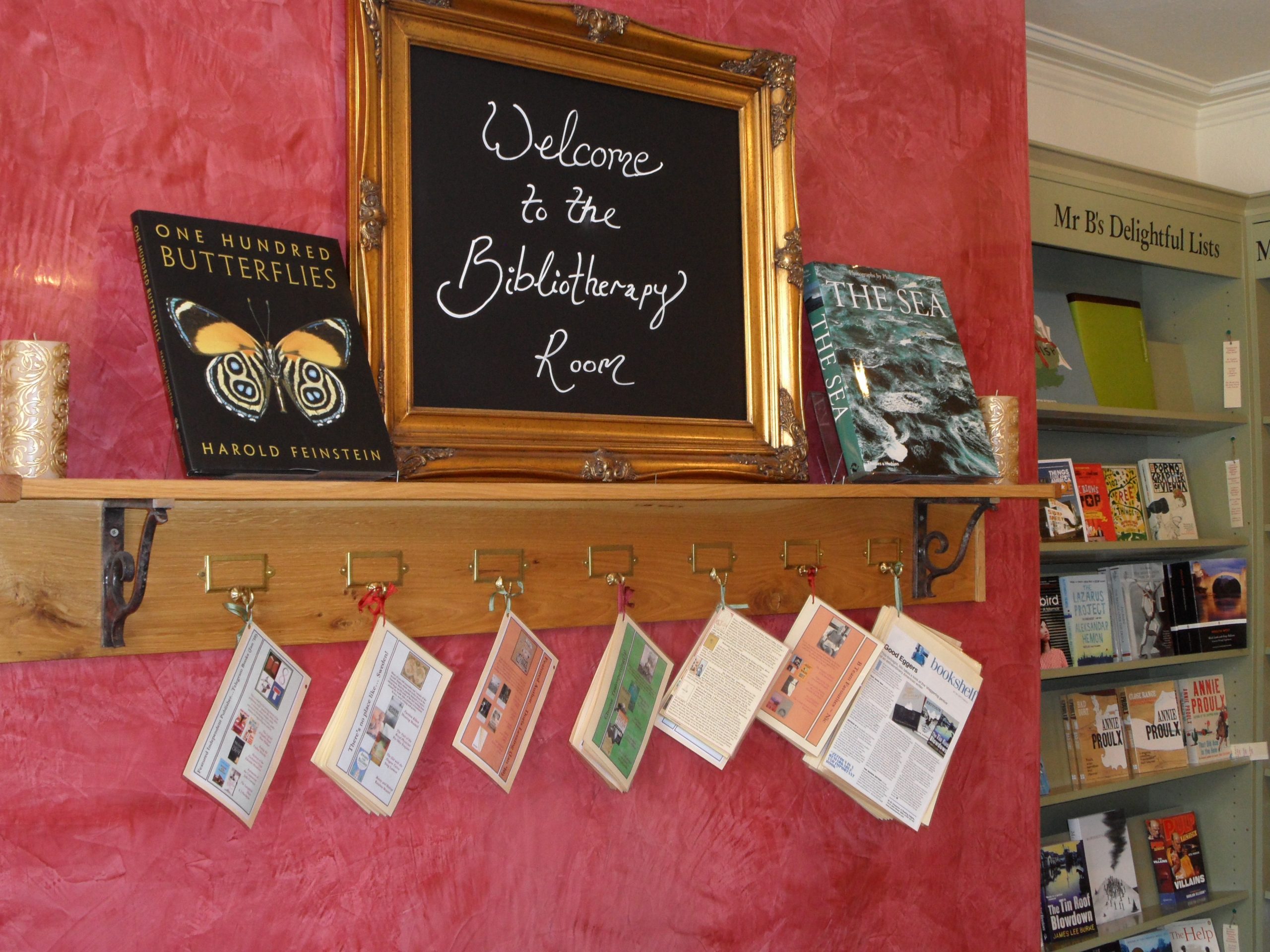

Bibliotherapy

Bibliotherapy uses books to help children express feelings in a supportive environment, gain insight into feelings and behavior, and learn new ways to cope with difficult situations. When children listen to or read a story, they identify with the characters and experience a catharsis of feelings. Stories and books should be selected based on the child’s cognitive and developmental levels that reflect the situations or feelings the child is experiencing and their emotional readiness for the topic.[26] See Figure 12.10[27] for an image of bibliotherapy.

Expressive Arts Therapy

Art provides a nonverbal method of expressing difficult or confusing emotions. Drawing, painting, and sculpting with clay are commonly used art therapies. Children who have experienced trauma often show the traumatic event in their drawing when asked to draw whatever they wish.[28]

Journaling

Journaling is an effective technique for older children and teenagers. Journaling is a tangible way to record emotions and begin dialogue with others. A daily journal is also helpful in setting goals and evaluating progress.[29]

Music Therapy

Music has been recognized for centuries as having healing power. Music therapy is an evidence-based approach to improve an individual’s physical, psychological, cognitive, behavioral, and social functioning when listening to music, singing, or moving to music.[30] See Figure 12.11[31] for an image of music therapy.

Family Education and Support

Education of family members is a key component for treating child and adolescent mental health disorders. Read more about “Parent Training in Behavior Management” in the “Psychological Therapies and Behavioral Interventions” section. Nurses can help family members develop specific goals and identify interventions to achieve their family’s goals.

Family members can also be encouraged to attend support groups or group education. Group education can be useful for learning how other families solve problems and build on strengths while developing insight and improved judgment about their own family.[32]

Find support groups for many disorders near you at Psychology Today’s Support Groups.

Implementation

Treatment of mental health disorders in children and adolescents typically requires a combination of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Read about specific multidisciplinary treatments for various disorders in the “Psychological Therapies and Behavioral Intervention,” “Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder,” and “Autism Spectrum Disorder” areas of this chapter. Nurses should recognize and capitalize on the client’s and family’s strengths as they develop a nursing care plan and provide education and referral to resources as appropriate.

Disruptive Behavior Management

Nurses can manage a child’s or adolescent’s disruptive behaviors by implementing many different types of interventions[33]:

- Behavioral contract: A verbal or written agreement is made between the client and other parties (e.g., nurses, parents, or teachers) about behaviors, expectations, and needs. The contract is periodically reviewed with positive and negative reinforcement provided.

- Collaborative and proactive solutions: The identification of problematic behaviors, their specific triggers, and mutually agreeable solutions.

- Role playing: The nurse or client acts out a specific role to practice new behaviors or skills in specific situations.

- Planned ignoring: When behaviors are determined to be attention-seeking and not dangerous, they may be ignored. Positive reinforcement is provided for on-task actions.

- Signals or gestures: An adult uses a word, gesture, or eye contact to remind the child to use self-control. For example, placing one’s finger to one’s lips and making eye contact may be used to remind a child to remain quiet during a quiet activity.

- Physical distance: It may be helpful to move closer to a child for a calming effect. However, some children may find this agitating and require more space and less physical closeness.

- Redirection: The engagement of an individual in an appropriate activity after an undesirable action.

- Humor: Appropriate joking can be used as a diversion to help relieve feelings of guilt or fear.

- Restructuring: The process of changing an activity to reduce stimulation or frustration.

- Limit setting: The process of giving direction, stating an expectation, or telling a child what to do or where to go. Caregivers and/or staff should do this firmly, calmly, and consistently without anger, preferably in advance of problem behavior occurring. For example, “I would like you to stop turning the light on and off.”

- Simple restitution: The individual is expected to correct the adverse effects of their actions, such as apologizing to the people affected or returning upturned chairs to their proper position.

Restrictive Interventions

Restrictive interventions are only implemented after attempting less restrictive interventions that did not successfully manage the client’s behavior. As a last resort, restrictive interventions, including seclusion or restraints, may be implemented to keep the client or others around them safe.[34]

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and The Joint Commission (TJC) define seclusion as the involuntary confinement of a client alone in a room or area from which the client is physically prevented from leaving. Restraint is defined as any manual method, physical or mechanical device, material, or equipment that immobilizes or reduces the ability of a patient to move their arms, legs, body, or head freely. A drug is considered a restraint when it is used as a restriction to manage the patient’s behavior or restrict the patient’s freedom of movement and is not a standard treatment or dosage for the patient’s condition.[35]

Seclusion is viewed as less restrictive than restraints, but seclusion and restraint are psychologically harmful and can be physically dangerous. Nurses must vigilantly follow agency policy when implementing seclusion or restraints. Members of the health care team who assist with seclusion or restraint of children or adolescents must receive specific training to decrease the risk of injury to the youngster and themselves.[36]

Seclusion and restraints should be discontinued as soon as possible. Clients in seclusion or restraints must be continuously monitored. Hydration, elimination, comfort, and other psychological and physical needs must be monitored regularly and addressed per agency policy.[37]

After the child or adolescent is calm, staff should include the child in a debriefing session and discuss the events leading up to the restrictive interventions to explore ways it may have been prevented.[38]

Evaluation

Evaluation focuses on monitoring a child’s and adolescent’s progress towards meeting their individualized SMART goals and the revision of the nursing care plan as needed. Client progress monitoring may include symptom management, behavior management, academic performance, activities of daily living, and socialization. The nurse also monitors effectiveness of interprofessional treatments, support groups, and community resources for the client’s families.

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Hilt, R. J., & Nussbaum, A. M. (Eds.). (2016). DSM-5 pocket guide for child and adolescent mental health. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9781615370511 ↵

- Middleman, A. B., & Olson, K. A. (2021, August 10). Confidentiality in adolescent health care. UpToDate. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- Middleman, A. B., & Olson, K. A. (2021, August 10). Confidentiality in adolescent health care. UpToDate. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Jabbari & Rouster and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Jabbari & Rouster and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Jabbari & Rouster and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Middleman, A. B., & Olson, K. A. (2021, August 10). Confidentiality in adolescent health care. UpToDate. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from www.uptodate.com ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Jabbari & Rouster and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Jabbari & Rouster and is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Ackley, B., Ladwig, G., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnosis handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care (12th ed.). Elsevier. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 23). Therapy to improve children’s mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/parent-behavior-therapy.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, February 24). Data and statistics on children’s mental health. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019, November 5). Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/aces/index.html ↵

- This image is derived from “Preventing Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs): Leveraging the Best Available Evidence” by National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Violence Prevention and is in the Public Domain ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- “4885680339_721cd1843e_k” by World Bank Photo Collection is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- “Bibliotherapy.jpg” by Shelley Rodrigo is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- “103909417_f36b60ceec_k” by midiman is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Knox, D. K., & Holloman, G. H., Jr. (2012). Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: Consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA seclusion and restraint workgroup. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6867 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Knox, D. K., & Holloman, G. H., Jr. (2012). Use and avoidance of seclusion and restraint: Consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project BETA Seclusion and Restraint Workgroup. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 13(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2011.9.6867 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

Traumatic circumstances experienced during childhood such as abuse, neglect, or growing up in a household with violence, mental illness, substance use, incarceration, or divorce.

Encourages children to express feelings such as anxiety, self-doubt, and fear through their natural play.

A behavioral intervention that uses books to help children express feelings in a supportive environment, gain insight into feelings and behavior, and learn new ways to cope with difficult situations.

An evidence-based approach to improve an individual’s physical, psychological, cognitive, behavioral, and social functioning when listening to music, singing, or moving to music.