Anxiety is a universal human experience that includes feelings of apprehension, uneasiness, uncertainty, or dread resulting from a real or perceived threat.[1] Fear is a reaction to a specific danger, whereas anxiety is a vague sense of dread to a specific or unknown danger. However, the body reacts physiologically with the stress response to both anxiety and fear.[2] See an artistic depiction of a person facing their feelings of anxiety from a perceived threat in Figure 9.1.[3] Review the stress response in the “Stress, Coping, and Crisis Intervention” chapter.

Levels of Anxiety

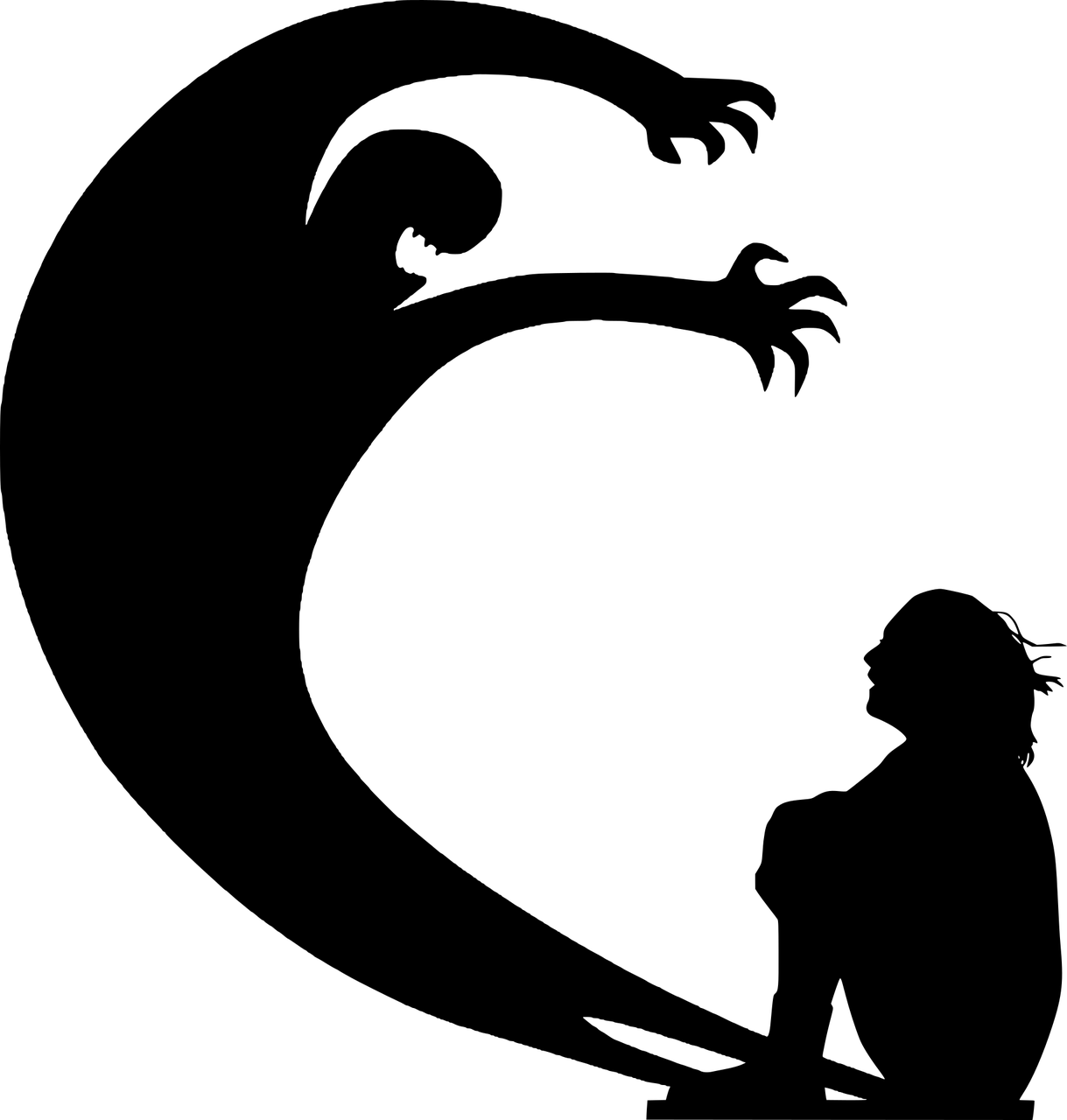

Hildegard Peplau, a psychiatric mental health nurse theorist, developed a model describing four levels of anxiety: mild, moderate, severe, and panic. Behaviors and characteristics can overlap across these levels, but it can be helpful to tailor interventions based on the level of anxiety the client is experiencing.[4]

Mild

Mild anxiety is part of everyday living and can help an individual use their senses to perceive reality in sharp focus. Symptoms of mild anxiety include restlessness, irritability, or mild tension-relieving behaviors such as finger tapping, fidgeting, or nail biting.[5]

Moderate Anxiety

As anxiety increases, the perceptual field narrows, and the ability of the individual to fully observe their surroundings is diminished/reduced. The person experiencing moderate anxiety may demonstrate selective inattention where only certain things in the environment are seen or heard unless they are pointed out. The individual’s ability to think clearly, learn, and problem solve is hampered, but can still take place. The physiological stress response kicks in with symptoms such as perspiration, elevated heart rate, and elevated respiratory rate. The individual may also experience headaches, gastric discomfort, urinary urgency, voice tremors, and shakiness; however, they may not be aware these symptoms are related to their level of stress and anxiety.[6]

Severe Anxiety

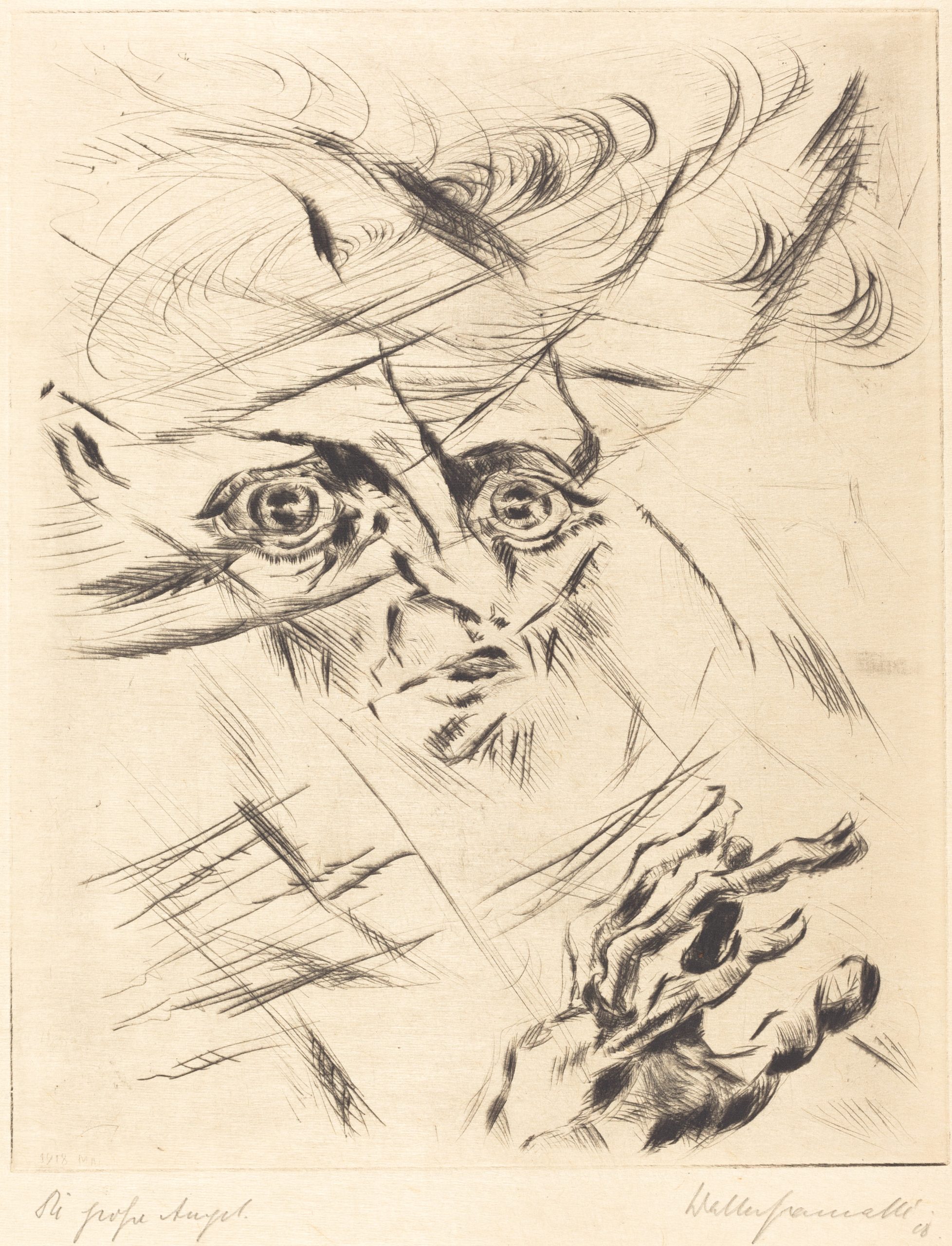

The perceptual field of a person experiencing severe anxiety is greatly reduced. They may either focus on one particular detail or on many scattered details. They often have difficulty noticing what is going on in their environment, even if it is pointed out; they may appear dazed or confused with automatic behavior. Learning, problem-solving, and critical thinking are not possible at this level. Symptoms of the stress response intensify and may include hyperventilation, a pounding heart, insomnia, and a sense of impending doom.[7] See Figure 9.2[8] for an artist’s rendition of severe anxiety.

Panic

Panic is the most extreme level of anxiety that results in significantly dysregulated behavior. The individual is unable to process information from the environment and may lose touch with reality. They may demonstrate behavior such as pacing, running, shouting, screaming, or withdrawal, and hallucinations may occur. Acute panic can lead to exhaustion.[9]

Coping with Anxiety

Individuals may use several strategies to cope with anxiety. Coping strategies are an action, a series of actions, or a thought process used to address a stressful or unpleasant situation or modify one’s reaction to such a situation. Coping strategies are classified as adaptive or maladaptive. Adaptive coping strategies include problem-focused coping and emotion-focused coping. Problem-focused coping typically focuses on seeking treatment such as counseling or cognitive behavioral therapy. Emotion-focused coping includes strategies such as engaging in mindfulness, meditation, or yoga; using humor and jokes; seeking spiritual or religious pursuits; engaging in physical activity or breathing exercises; and seeking social support. Maladaptive coping responses include responses such as avoidance of the stressful condition, withdrawal from a stressful environment, disengagement from stressful relationships, and misuse of alcohol or other substances.

Defense mechanisms are reaction patterns used by individuals to protect themselves from anxiety that arises from stress and conflict. Adaptive use of defense mechanisms can help people achieve their goals, but excessive or maladaptive use of defense mechanisms can be unhealthy.[10] Excessive use of defense mechanisms are associated with specific mental health disorders.

Risk Factors for Anxiety Disorders

Occasional anxiety is an expected part of life. It is common to feel anxious when faced with a problem at work, before taking a test, or before making an important decision. However, anxiety disorders involve more than temporary worry or fear. For a person with an anxiety disorder, the anxiety does not go away and can worsen over time, and their symptoms can interfere with daily activities such as job performance, schoolwork, and relationships.[11]

Researchers have found that both genetic and environmental factors contribute to the risk of developing an anxiety disorder. Although the risk factors for each type of anxiety disorder can vary, some general risk factors for all types of anxiety disorders include the following[12]:

- Temperamental traits of shyness or behavioral inhibition in childhood

- Exposure to traumatic life or environmental events in early childhood or adulthood

- A history of anxiety or other mental health disorders in biological relatives

Some medical conditions (such as thyroid problems, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and angina) or substances (such as caffeine, certain prescribed medications, or illicit drugs) can also cause symptoms of anxiety. When a client is initially evaluated for anxiety, a physical health examination is performed to rule out other potential causes of their anxiety symptoms.

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- “fear-g84d457182_1280” by mohamed_hassan on Pixabay.com is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- “Walter_Gramatté,_Die_Grosse_Angst_(The_Great_Anxiety),_1918,_NGA_71292.jpg” by Walter Gramatté is licensed in the Public Domain ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Halter, M. (2022). Varcarolis’ foundations of psychiatric-mental health nursing (9th ed.). Saunders. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., & Kamitsuru, S. (Eds.). (2018). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2018-2020. Thieme Publishers New York. ↵

- National Institute of Mental Health. (n.d.). Any anxiety disorder. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/any-anxiety-disorder ↵

A universal human experience that includes feelings of apprehension, uneasiness, uncertainty, or dread resulting from a real or perceived threat.

The most extreme level of anxiety that results in significantly dysregulated behavior.

An action, series of actions, or a thought process used in meeting a stressful or unpleasant situation or in modifying one’s reaction to such a situation.

Reaction patterns used by individuals to protect themselves from anxiety that arises from stress and conflict.