Hearing in Complex Environments

72

Learning Objectives

Understand the separate roles of respiration, phonation, and articulation.

Know the difference between a voiced and an unvoiced sound.

The field of phonetics studies the sounds of human speech. When we study speech sounds, we can consider them from two angles. Acoustic phonetics, in addition to being part of linguistics, is also a branch of physics. It’s concerned with the physical, acoustic properties of the sound waves that we produce. We’ll talk some about the acoustics of speech sounds, but we’re primarily interested in articulatory phonetics—that is, how we humans use our bodies to produce speech sounds. Producing speech takes three mechanisms.

- The first is a source of energy. Anything that makes a sound needs a source of energy. For human speech sounds, the air flowing from our lungs provides energy.

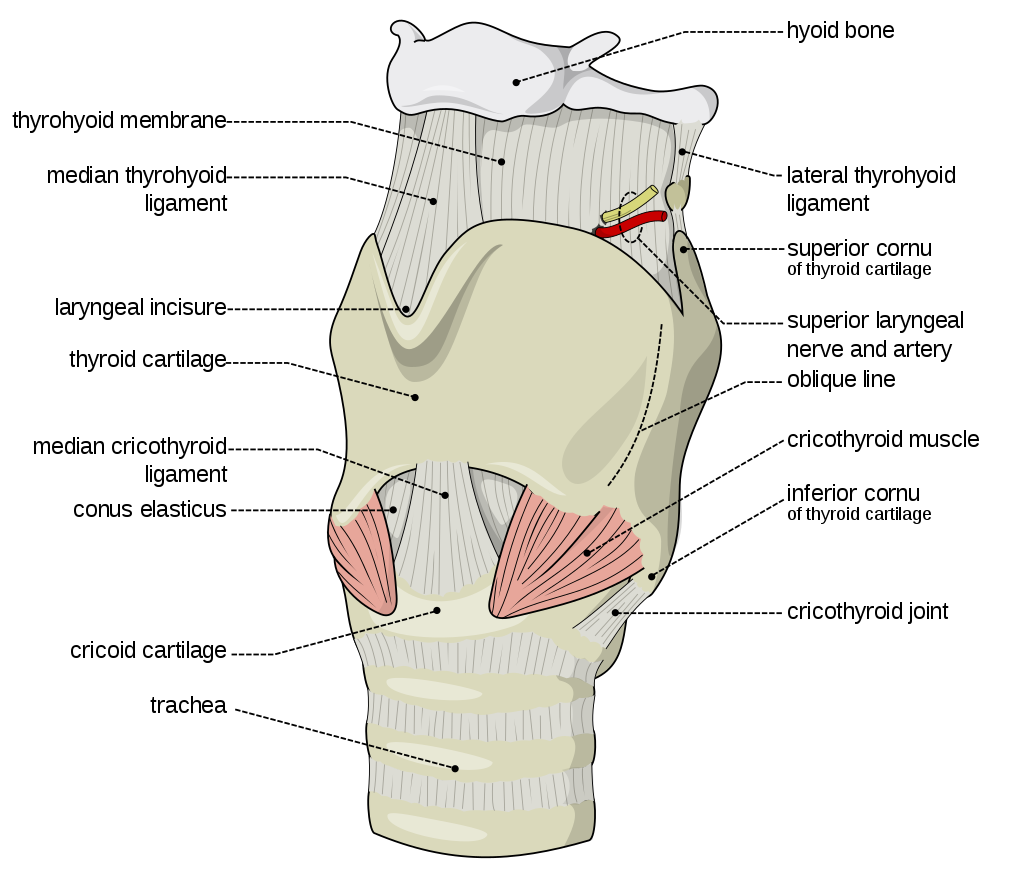

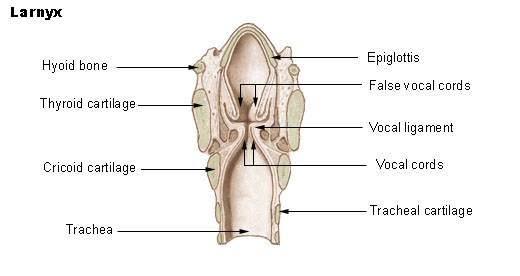

- The second is a source of the sound: air flowing from the lungs arrives at the larynx. Put your hand on the front of your throat and gently feel the bony part under your skin. That’s the front of your larynx. It’s not actually made of bone; it’s cartilage and muscle. This picture shows what the larynx looks like from the front:

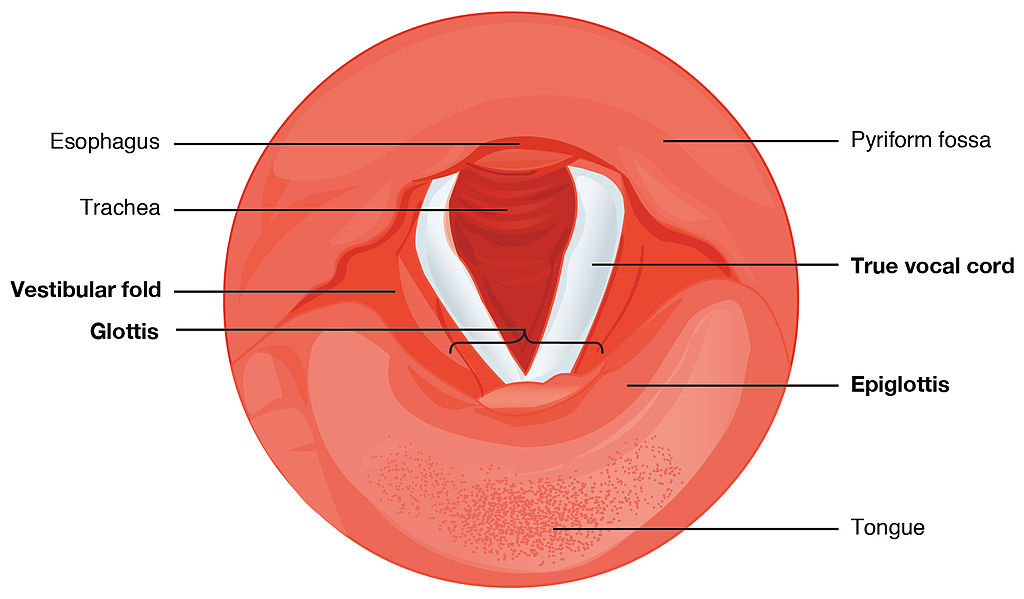

What you see here is that the opening of the larynx can be covered by two triangle-shaped pieces of tissue. These are often called “vocal cords” but they’re not really like cords or strings. A better name for them is vocal folds. The opening between the vocal folds is called the glottis.

We can control our vocal folds to make a sound. Try this out:

First I want you to say the word “uh-oh.” Now say it again, but stop half-way through (“uh-“). When you do that, you’ve closed your vocal folds by bringing them together. This stops the air flowing through your vocal tract. That little silence in the middle of uh-oh is called a glottal stop because the air is stopped completely when the vocal folds close off the glottis. Now I want you to open your mouth and breathe out quietly, making a sound like “haaaaaaah.” When you do this, your vocal folds are open and the air is passing freely through the glottis. Now breathe out again and say “aaah,” as if the doctor is looking down your throat. To make that “aaaah” sound, you’re holding your vocal folds close together and vibrating them rapidly. When we speak, we make some sounds with vocal folds open, and some with vocal folds vibrating. Put your hand on the front of your larynx again and make a long “SSSSS” sound. Now switch and make a “ZZZZZ” sound. You can feel your larynx vibrate on “ZZZZZ” but not on “SSSSS.” That’s because [s] is a voiceless sound, made with the vocal folds held open, and [z] is a voiced sound, where we vibrate the vocal folds. Do it again and feel the difference between voiced and voiceless. Now take your hand off your larynx and plug your ears and make the two sounds again. You can hear the difference between voiceless and voiced sounds inside your head.

There are three crucial mechanisms involved in producing speech, and so far we’ve looked at only two (listed as the first two below):

- Energy comes from the air supplied by the lungs.

- The vocal folds produce sound at the larynx.

- The sound is then filtered, or shaped, by the articulators.

The oral cavity is the space in your mouth. The nasal cavity, as we know, is the space inside and behind your nose. And of course, we use our tongues, lips, teeth and jaws to articulate speech as well. In the next unit, we’ll look in more detail at how we use our articulators.

So to sum up, the three mechanisms that we use to produce speech are:

- respiration at the lungs

- phonation at the larynx

- articulation in the mouth

Essentials of Linguistics, Chapter 2.1 How Humans Produce Speech by Catherine Anderson

URL: https://essentialsoflinguistics.pressbooks.com/chapter/2-2-how-humans-produce-speech/

License: CC BY SA 4.0

Adapted by: Lilly McLaughlin