Hearing Loss and Central Auditory Processing

52

Learning Objectives

Understand the conditions in which cochlear implant can be an option.

Understand how cochlear implants are implemented.

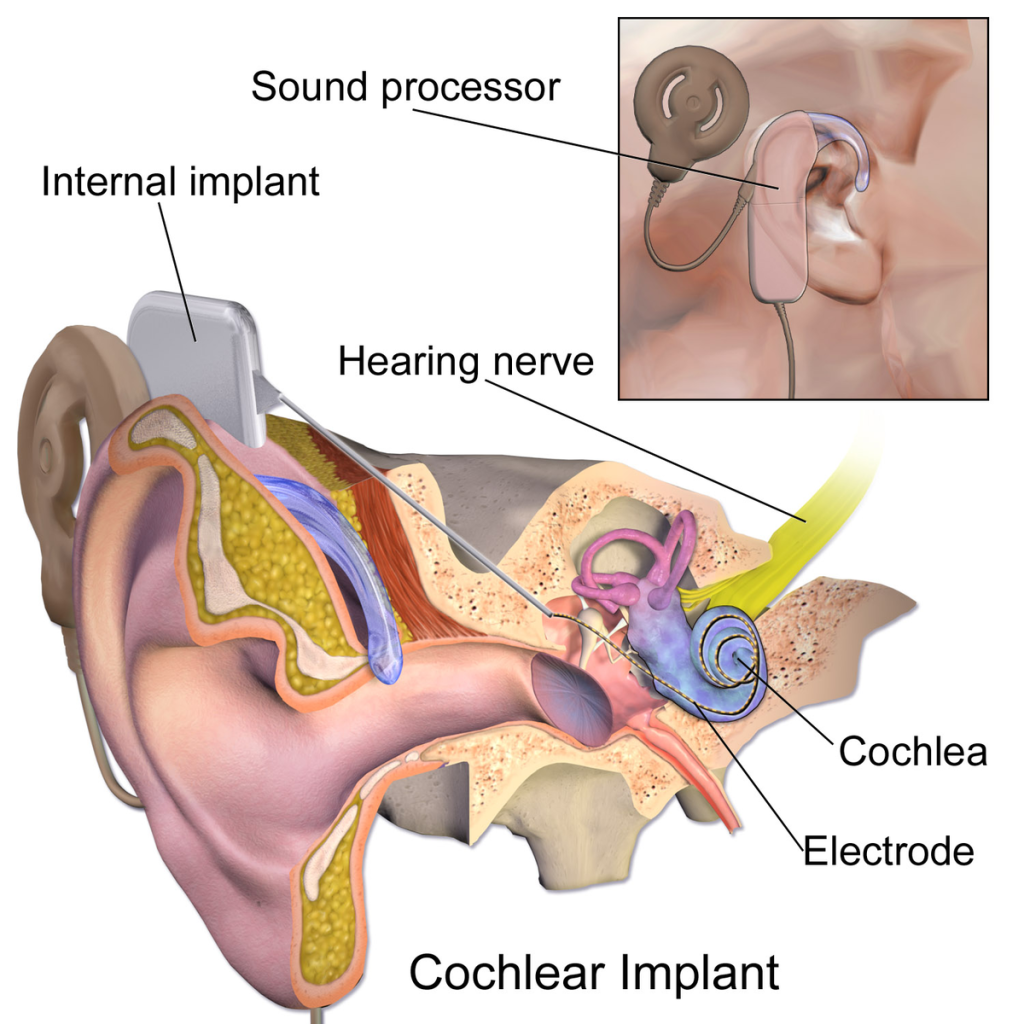

When the hearing problem is associated with a failure to transmit neural signals from the cochlea to the brain, it is called sensorineural hearing loss. One disease that results in sensorineural hearing loss is Ménière’s disease. Although not well understood, Ménière’s disease results in a degeneration of inner ear structures that can lead to hearing loss, tinnitus (constant ringing or buzzing), vertigo (a sense of spinning), and an increase in pressure within the inner ear (Semaan & Megerian, 2011). This kind of loss cannot be treated with hearing aids, but some individuals might be candidates for a cochlear implant as a treatment option. Cochlear implants are electronic devices that consist of a microphone, a speech processor, and an electrode array. The device receives incoming sound information and directly stimulates the auditory nerve to transmit information to the brain.

A cochlear implant is very different from a hearing aid. Hearing aids amplify sounds so they may be detected by damaged ears. Cochlear implants bypass damaged portions of the ear and directly stimulate the auditory nerve. Signals generated by the implant are sent by way of the auditory nerve to the brain, which recognizes the signals as sound. Hearing through a cochlear implant is different from normal hearing and takes time to learn or relearn. However, it allows many people to recognize warning signals, understand other sounds in the environment, and understand speech in person or over the telephone.

Children and adults who are deaf or severely hard-of-hearing can be fitted for cochlear implants. Use of a cochlear implant requires both a surgical procedure and significant therapy to learn or relearn the sense of hearing. Not everyone performs at the same level with this device. The decision to receive an implant should involve discussions with medical specialists, including an experienced cochlear-implant surgeon. The process can be expensive. For example, a person’s health insurance may cover the expense, but not always. Some individuals may choose not to have a cochlear implant for a variety of personal reasons. Surgical implantations are almost always safe, although complications are a risk factor, just as with any kind of surgery. An additional consideration is learning to interpret the sounds created by an implant. This process takes time and practice. Speech-language pathologists and audiologists are frequently involved in this learning process. Prior to implantation, all of these factors need to be considered. As of December 2012, approximately 324,200 registered devices have been implanted worldwide. In the United States, roughly 58,000 devices have been implanted in adults and 38,000 in children. (Estimates provided by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA], as reported by cochlear implant manufacturers.)

CC LICENSED CONTENT, SHARED PREVIOUSLY

OpenStax, Psychology Chapter 5.4 Hearing

Provided by: Rice University.

Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/4abf04bf-93a0-45c3-9cbc-2cefd46e68cc@5.103.

License: CC-BY 4.0

National Institutes of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD), Cochlear Implants

URL: https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/cochlear-implants

License: public domain

Adapted by: Yichen Dai