2 “Upon Grounds Appealing to the Conscience of All Men” Laurier, Bowell, Tupper, and the Manitoba School Question

Isaac Farrell

Introduction:

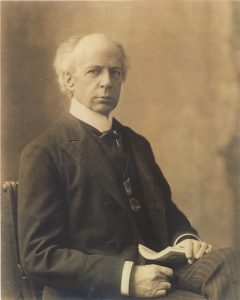

Few political issues have dominated Canadian politics to the degree that the Manitoba School Question did between 1890 and 1896. Centred around education funding for a French Catholic minority that was rapidly declining in both population and influence, the Manitoba School Question essentially began with the 1890 Manitoba Schools Act, which removed public funding from confessional schools and abolished the dual-denomination system.[1] However, due to its mishandling by a federal Conservative government that had been weakened by the death of Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, and growing tensions between Canada’s French and English-speaking populations, the Manitoba School Question quickly evolved from a regional dispute over language and education rights into a direct challenge on the national stage, with the constitutional authority of both the federal and provincial governments serving as the battlefield. The controversy was only heightened by subsequent actions taken by the government of Manitoba led by Premier Thomas Greenway, whose government acted to eliminate French as an official language in nearly every aspect of Manitoba life, including in its legislation.[2] The Manitoba School Question became a career-defining moment for several Canadian politicians as it grew in importance through two federal election campaigns and at least five separate federal mandates. For the governments of Prime Ministers Mackenzie Bowell and Charles Tupper, their inability to handle the situation spelled the premature end of their time in office and ultimately defined their legacies. On the other hand, no one benefited more from the Manitoba School Question than Liberal Party leader Wilfrid Laurier. Laurier’s skillful political maneuvering, highlighted by a series of colourful speeches in 1895 and 1896 in which he appealed to the “conscience of all men” and showed a willingness to take the “Sunny Way”[3] of political compromise, earned him the first of four majority election victories in 1896 and kickstarted the beginning of his record-setting fifteen consecutive years in office. The Laurier-Greenway Compromise followed five months later and ended the Manitoba School Question in the short term, but failed to address its underlying causes. However, it was also an early example of the diplomatic approach that would soon make Laurier a giant in Canadian politics for the rest of his life.

Background History:

Although the School Question officially began in 1890, its roots stretched back at least twenty years to the founding of Manitoba as a province. Changes in demographics were almost certainly the most significant cause of the crises. At the time of the Manitoba Act of 1870, the population in the province stood at roughly 12,000, of which fifty-four percent were French-speaking Metis.[4] Thus, when the first Manitoba School Act of 1871 regulated education under a Board of Education that was “divided” into two “largely autonomous”[5] Protestant and Catholic sections, a separate school system was not only sustainable but “absolutely necessary and logical.”[6] However, the population dynamics changed almost immediately, and within a decade there were more Manitobans who had been born in Ontario than those who were born in Manitoba.[7] By 1881, French speakers only represented twelve percent of Manitoba’s population, which had ballooned to over 65,000, of which “fewer than 10,000 were French.”[8] In the province’s largest settlement, Winnipeg, a city that grew from 700 in 1871 to 23,000 in 1891 and 200,000 by 1916, French speakers constituted less than five percent of the population by 1881.[9] By 1891, the membership of the Presbyterian, Methodist, and Anglican churches alone made up sixty-four percent of Manitoba’s population, while the Roman Catholic portion represented less than ten percent.[10] Thus, to the Anglo-Canadian majority, by 1875 the separate school system had become merely “convenient” to keep around, by 1878 it was a “nuisance,”[11] and by 1889 it was inefficient and unsustainable. After the North-West Territories Act failed to give French official status in 1875,[12] similar bills were introduced in Manitoba to repeal the separate school system as early as 1875 and 1876, and although they failed to gain momentum, a bill to remove French as an official language would have succeeded in 1879 if not for the presence of a French Catholic Governor General, who vetoed it.[13] Tensions only increased throughout the period, as the 1870s saw the highly-publicized Red River trials as well the movement of the anti-Catholic Orange Order into the province.[14] As a result, while French rights in Manitoba were not officially challenged again until 1889,[15] the wheels for a major conflict were already turning at least a decade earlier.

Tensions between the two sides grew as the British nature of Western Canadian society became more pronounced after the 1885 North-West Rebellion and the subsequent execution of Louis Riel, which caused tensions between French and Anglo-Canadians to reach an all-time high. Anglo-Canadians felt betrayed by French Canada’s overwhelming support for both the rebellion and Riel,[16] and this sentiment led territorial politicians to try and do away with the French language and separate school guarantees across the country under the motto “one nation, one language.”[17] Newspapers such as the Brandon Sun and the Winnipeg Free Press were influenced by the gradual “influx” into the province of “numerically dominant, racially proud, and socially intolerant” British Protestants, who were “strongly supportive of both secular schools and the attempt to eliminate all cultural differences among the general population,”[18] and began to call for an end to the school system in late 1888 and, more frequently, after May 1889.[19] Thus, while the School Question may have come unexpectedly “out of a clear blue sky” to those outside Manitoba,[20] for Manitobans the process was a gradual “outgrowth of firmly entrenched local conditions.”[21]

The Manitoba School Act and the Official Language Act:

A new “local outgrowth” came with the appointment of new Liberal Premier Thomas Greenway in 1888. Greenway was asked to fill the position after Conservative Premier John Norquay was forced to resign in December 1887 due to his mishandling of Manitoba’s railway transfer crisis, and after Norquay’s initial replacement, David Howard Harrison, failed to form a new government within the first week of his appointment.[22] After his appointment, Greenway called and subsequently dominated a provincial election later that year, but as his government struggled to resolve those same railway transfer issues during the summer and winter of 1888,[23] Greenway needed a distraction. That distraction came as early as January and in the form of education reform. By that point, the strains of the separate school system were starting to become a matter of concern for the English-speaking and Protestant-believing majority, who had contributed an increasingly large portion of both the enrolment numbers and the taxes that went towards the school board.[24] Thus, in an announcement of a planned review of education funding, Greenway stated: “Owing to peculiar circumstances, the charge upon the taxpayers for educational purposes is abnormally heavy [and so] the Government will devise means whereby the schools will receive a much larger money grant than has heretofore been given.”[25] The concern of the majority grew into anxiety when the government review learned of a Catholic “contingency fund” that amounted to nearly $14,000.[26] This discovery caused the Catholic Section to fear for its future and the Protestant Section to believe their counterparts had “received favourable treatment in the distribution of government funds,” and thus this discovery arguably “marked the beginning of the Manitoba School Question.”[27] As a result, the Greenway government decided to “economize” by replacing the inefficient separate system with one that placed “Roman Catholic schools under much stricter control”[28] by “abolish[ing] the Board of Education and plac[ing] educational affairs directly under the administration of a minister of the crown,” a system similar to the one adopted in Ontario in 1876.[29] However, as this plan did not propose to remove religious education, it caused “considerable apprehension to the board and its two sections”[30] in roughly equal amounts. It was not until August that the debate turned towards abolishing Roman Catholic schools altogether, a turn that caused anxieties within the Roman Catholic community to reach a fever pitch.

On 5 August 1889, D’alton McCarthy, a Conservative Member of Parliament visiting Manitoba and the North-West Territories from Ontario and a “spokesman for the Equal Rights Association,”[31] gave a speech in Portage la Prairie. In response to the 1888 Jesuit Estates Act, which monetarily reimbursed Jesuits in Québec for the land confiscations and cultural suppression that had been imposed on them by the British after 1763, the ardently anti-Catholic and anti-French McCarthy “encouraged his audience to support an attack on the French Roman Catholic minority” to resist similar “inequalities”[32] from occurring to the English of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. While McCarthy said nothing of the school system, his speech “vastly increased” the “tone and bitterness”[33] of the debate. Additionally, it was followed by a similar speech given by Manitoba Attorney General, Joseph Martin, in which Martin pledged that the Greenway government would put an end to both French as an official language and the separate school system in the province.[34]

Initial Response to the Manitoba School Act:

The Manitoba School Act and the Official Language Act were immensely popular with most Protestants and English Canadians,[35] not only in Manitoba — where they helped propel Greenway to another majority in 1892 — but also across Canada. Conversely, the opposite was true of French Canadians and Catholics. Backlash towards the two Acts came almost immediately, primarily from local French and Roman Catholic communities but also from Quebec, where the development took many by surprise and was perceived as a push towards making Western Canada, which at that time was seen as representing the future of Canada, culturally and linguistically English. However, as the community was pressed both by time and resources,[36] they were forced to choose between contesting the Official Language Act or the Manitoba School Act. As education was crucial to linguistic and religious retention, they chose the latter.

Led by Archbishop Alexandre Tache of St. Boniface, Manitoba, and his “astute legal counsel,” J.S. Ewart,[37] the Roman Catholic community in the province first appealed to the Manitoba court system through Barrett v. the City of Winnipeg, a case in which Ewart represented John Barrett, a Winnipeg resident who “refused to pay the municipal tax for the support of the public schools … alleging that, as a Roman Catholic, his constitutional rights … were being violated.”[38] After Ewart lost in the first hearing, the case was appealed, first, to the Court of the Queen’s Bench of Manitoba, which found the Manitoba School Act to be intra vires, and then to both the Supreme Court and the federal government of Conservative Prime Minister John A. Macdonald, to whom they argued that the new public school system in Manitoba was “in reality a continuation of the Protestant school” system in the “guise” of a secular one, one in which Catholic children were forced to go to Protestant schools by the closing of Catholic schools. Thus, they argued that “only the Roman Catholics had been forced to make significant changes and endure hardships.”[39] Ewart claimed this made the “new laws unconstitutional”[40] under Section 23 of the Manitoba Act and Subsections 1 and 2 of Section 93 of the British North America Act, which included guarantees that established separate education rights for minorities in Upper and Lower Canada.[41]

Ewart and Tache’s federal appeal was met more with “sympathy than direct action.”[42] Macdonald initially “refused to interfere with the school law of the province,”[43] and instead deferred becoming involved until the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, the highest court in Canada at the time, made a decision. In his response, which McCarthy (who by then had switched allegiances to the Liberals) would later describe as the last action taken by the government which he could “commend,”[44] Macdonald said:

If the appeal should be successful these acts will be annulled by judicial decision, the Roman Catholic minority in Manitoba will receive protection and redress. The acts purporting to be repealed will remain in operation… if the legal controversy should result in the decision… being sustained, the time will come for… the petitions which have been presented by and on behalf of the Roman Catholics of Manitoba for redress… under section 22 of the Manitoba Act… and which are analogous to the provisions made by the British North America Act.[45]

Thus, Macdonald sent Ewart away with a promise that “if the law turned out to be within the constitutional power of the province to pass, the Government here would entertain the question”[46] in regards to the Manitoba constitution. This was a promise that would soon have drastic implications. After a separate hearing in 1891 on the Manitoba School Act, the Privy Council inconclusively ruled that “Manitoba had acted within its rights but that the federal government also had the right to issue its own replacement legislation” and that it had “affected the minority’s rights adversely.”[47] The issue was thereby pushed out of the courts and into the realm of politics.[48] Ewart and Tache turned once more to the Macdonald government, which responded by ordering the Greenway government to provide public support to the Catholic schools.[49] Greenway ignored the order, and the “legislation proposed by King’s government to address the issue was interrupted by the 1891 federal election,” because King was concerned that forcing the issue could potentially hurt his chances of re-election.[50] Macdonald defeated Leader of the Opposition Wilfrid Laurier, who was making his first election appearance, but it would be the last Conservative victory until 1911.

The Manitoba School Question:

Macdonald suffered an untimely stroke on May 27, the same day the Supreme Court first heard Ewart’s appeal in the Barrett case,[51] and died on June 6, only three months after the 1891 election. On October 28, Supreme Court sided with Ewart and against both the Manitoba government and the Manitoba courts, which they said had acted ultra vires.[52] This, too, was appealed to the Privy Council with a hearing set for 1892, and as the country awaited the Council’s decision, debates over the Manitoba School Question stalled.[53] By the time the Barrett decision finally came in mid-1892 and handed the problem back to the federal government,[54] the health of Macdonald’s successor, John Abbott, was already in decline,[55] putting the Conservative Party in a state of unstable leadership for the first time in decades. Abbott resigned in November and was replaced by John Thompson, who was the first Catholic Prime Minister;[56] this soon became a matter of particular contention regarding the School Question, as he had converted from Protestantism as an adult.[57] Thompson’s first action was to appeal to the Privy Council once again,[58] this time through Brophy v. the Attorney-General of Manitoba. His second action was to force his government to “reluctantly [take] a stand”[59] against the Manitoba government. However, what that stand would look like was yet to be determined. On 28 November, the Ottawa World captured Thompson’s lack of clarity, as well as the total uncertainty which surrounded the case, with the following:

Sir John Thompson… is unpledged publicly or privately in the matter, and he is not now going to pledge himself or his party on a question that cannot come up as a political issue for a few years [due to the Brophy case]… For the present, separate schools for Manitoba are impossible, and the Roman Catholics must accept it as such. This really relieves [Thompson] and his party of a troublesome question and gives him a free hand.[60]

As the debate over the School Question centred around the intentions behind the making of Section 93 of the British North America Act, politicians from both parties did their best to challenge the clarity of the constitutional guarantees. The issue stemmed from whether or not the guarantees covered religious minorities across the country or solely those in Ontario and Quebec, and whether or not the provincial governments had the power to revoke those guarantees.[61] These guarantees were, in fact, “explicit and unambiguous,” as the Official Language Act was eventually ruled unconstitutional in 1979,[62] and the Manitoba Act only succeeded because “notions of constitutionalism and ‘constitutional guarantees’ were vague and subject to a variety of interpretations.”[63] Those interpretations often centred around racial stereotypes, with the intellectual capacity of the Métis involved in the drafting of the Manitoba Act being questioned. For example, Bishop A.B. Bethune of Toronto based his argument against the Metis on a description from 1871:

“The French half breed, called also Métis… is an athletic, rather good-looking, lively, excitable, easy-going being. Fond of a fast pony, fond of merry-making, free-hearted, open-handed, yet indolent and improvident, he is a marked feature of border life.” It is this wild and intractable, but still attractive, child of the plains who, we are asked to believe, was so calculatingly solicitous to secure the permanency of Roman Catholic separate schools. “As different as is the patient roadster from the wild mustang, is the English-speaking half-breed from the Métis.”[64]

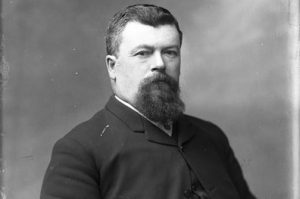

Early on, opposition leader Wilfrid Laurier was critical of the Conservative Government’s handling of the case, but he did not become directly involved. However, when discussions over a potential remedial order started to dominate Parliament in the spring of 1893, Laurier chose to pressure the government on the issue, starting with a speech given to Parliament in March 1893.[65] Framing the situation as the “simplest issue” and one in which the government simply needed to “express an opinion” one way or the other, Laurier “arraign[ed] [the] government for their arrant cowardice,” an expression he claimed was in no way “too strong” in the face of such “flimsiness” on behalf of the Conservatives.[66] Laurier claimed the Conservatives had avoided taking a stance on the issue for over three years when he could have addressed it in only one, which Laurier said proved there was not “in this government the courage equal to the duty of the hour.”[67] Laurier then accused Thompson of personally avoiding the issue, and sarcastically commended Thompson for his ability to “speak for two hours without having told the House what his policy was.”[68] While he described Thomas as an “able lawyer”[69] whose legal skills were well-known, Laurier argued that Thompson should have been disqualified from being involved in the case due to his personal history with both religions.[70] He also used the opportunity to begin discrediting the Conservative ministers tasked with handling the School Question. This included Mackenzie Bowell, the Minister of Trade and Commerce and a newspaper publisher, who had allegedly “never distinguished [himself] by [his] legal studies.”[71]

Using his legal background to full effect, Laurier framed the Manitoba School Question as a straightforward question of provincial versus minority rights, with his speech structured to sound like he already had a solution to the problem.[72] However, he did so without disclosing which side he agreed with. Comparing the situation of the French in Manitoba to that of the English Protestants in Québec, Laurier opined that the Fathers of Confederation had intended to ensure minority rights and that they not only guaranteed a separate school system but also separate school boards, saying “if the Catholic claim is true, though my life as a political man should therefore be ended forever… the minority has been subjected to a most infamous tyranny.”[73] However, he also reminded Parliament that the BNA Act empowered local legislatures to be “almost independent” in most policy areas and that in the case of separate schools, the federal government held only a “supervisory power.”[74]

This was the limit to which Laurier was willing to commit. While he agreed that the Catholics had the right to appeal and that the government was failing in its duty to honour that appeal, Laurier did not outright support the Catholics, and in fact, expressed sympathy for Greenway. He was also careful not to criticize the late Macdonald, instead highlighting how the high-ranking members of the Conservative Party had failed to follow the groundwork Macdonald had set on the issue: Laurier recalled that the Catholics had been instructed by Macdonald to appeal to the courts first, and if they failed, Macdonald had promised them his government was “endowed with judicial powers” and could “sit as a court”[75] on their issue. Thus, Laurier contended that the Conservatives had an obligation to the Catholics even after Macdonald’s death, and went so far as to accuse the government of “resort[ing] to every possible subterfuge in order to avoid coming to a decision.”[76] The Conservatives may have underestimated the significance of the Manitoba School Question, but Laurier made it clear he did not. In his closing remarks, Laurier blamed the governments of both Abbot and Thompson for “even now not having done sooner what they should have done” before going on to predict that, whenever the government “at last” made a decision, “the population will by that time have been excited to such a pitch that the condition will be scarcely distinguishable from open rebellion to the law… and when that decision comes… great disappointment is sure to result, and an impression will prevail that a great injustice has been done.”[77] Therefore, in using the case of the Catholics to appeal to the moral and religious fibre of every man in Parliament, Laurier, who had already made significant gains in the 1891 federal election, was setting the groundwork for his 1896 campaign.

The Conservative response to Laurier’s remarks was lacklustre, and further development throughout 1893 and 1894 was limited to debating the viability of a remedial order while the country waited on the Brophy case. The remedial order, which would theoretically force the Manitoba government to repeal both the Official Language Act and the School Act, was an issue that the Liberals adamantly opposed and that the Conservatives were split over. Matters were further complicated when Thompson suddenly and unexpectedly died at the age of 49 in December 1894, only a month before the Brophy decision was to be delivered. While Charles Tupper, High Commissioner to the United Kingdom, was believed to be the candidate best suited to be Thompson’s replacement, a combination of his “ill health” and the fact that “Governor General Lord Aberdeen and his influential wife disliked him,”[78] caused Mackenzie Bowell to become Prime Minister instead. That decision would soon prove to be a costly one.

The Election of 1896:

On 31 January 1895, the Privy Council ruled the Manitoba School Act constitutional but confirmed that, through a remedial order, the federal government was responsible for protecting the Catholic minority of Manitoba.[79] After deliberating on the decision for nearly two months, the Bowell government controversially issued a remedial order on 21 March demanding the Manitoba government to “restore the educational rights of its Catholic decisions”[80] that had been in place before 1890, a decision fervently critiqued by Laurier’s Liberals.[81] After discussions with Martin and the rest of his cabinet that lasted another two months, Greenway rejected the remedial order on 5 June. Greenway argued that the inefficiencies of the separate system made it impossible to comply, but that “with more information and negotiation, some compromise could be reached.”[82]

Bowell now had a full-blown crisis on his hands. Greenway’s refusal was a direct challenge to federal authority, but as Bowell’s party had already been split on the issue even before the remedial order, his options were limited. In July, Senator Auguste-Real Angers, Bowell’s Minister of Agriculture and a key representative from Quebec, handed in his resignation, and with two other French Canadian ministers threatening to do the same, Bowell was unable to replace him.[83] By December, “the government had lost two critical by-elections in Quebec over the school issue… and Nathaniel Clarke Wallace… the great anti-remedial in the ministry, had resigned.”[84] When another remedial bill was introduced to Parliament in January 1896, seven more threatened to resign from their cabinet positions if Bowell was not replaced by Tupper (and then temporarily did),[85] and, with his government falling apart around him, Bowell attempted to resign several times. However, since Tupper was still the clear choice to succeed him, these attempts were all rejected by Aberdeen.

Ever the politician, Laurier used this opportunity to transform his criticisms into an electoral strategy throughout 1895. With the Conservatives less unified than ever over the remedial order and with their 1891 mandate nearing its end, Laurier launched his election campaign with a speaking tour in the fall.[86] The tour peaked on 8 October, when Laurier gave what would become among the most famous speeches in Canadian history and the one that would most define his legacy: the “Sunny Way” speech. After stating that he was “not here to solve the question, because it [was] not in [his] province to solve it” but that he was not “afraid” to speak on it, Laurier invoked an Aesopean fable “in which the sun, representing kindness, and the wind, representing severity, [held] a contest”[87] to remove a traveller’s cloak by either warming them so that they willingly removed the coat or by blowing it off of them. Framing the Conservatives as the wind and Greenway as the traveller, Laurier vowed to try “the sunny way,” saying:

I would approach Greenway with the sunny ways of patriotism, asking him to be generous to the minority, in order that we may have peace amongst all the creeds and races… Do you not believe that there is more to be gained by appealing to the heart and soul of men rather than compelling them to do a thing? I intend to do so… to satisfy… every sensible man. [Greenway], I will meet you halfway.[88]

While Laurier continued to play his hand close to the chest by not “leaving the lines” until it was advantageous to do so,[89] his intent was clear: he was extending an olive branch to Greenway in the form of compromise. The response to this speech was rapturous, and from then on Laurier had a clear advantage heading into 1896. By this point, popular sentiment for English Canada had adopted the mantra that “the Manitobans of 1870 had no right to bind the Manitobans of 1895,”[90] and so in issuing the remedial order Bowell had surrendered much of the English vote. However, it had also taken so long for the Conservatives to adopt a stance that in their indecisiveness, they had already lost Quebec as well.[91]

By March of 1896, Laurier was adamant in placing the blame entirely on Bowell, and it seemed the rest of the country agreed. On 3 March, Laurier gave another powerful speech, in which he committed to taking a stand “not upon grounds of Roman Catholicism, not upon grounds of Protestantism, but upon grounds which can appeal to the conscience of all men… upon grounds which can be occupied by all men who love justice, freedom, and toleration.”[92] The reaction to Laurier’s speech was once again overwhelming, and with the time since the last election fast approaching the five-year mark, Aberdeen’s hand was forced. The government called for a new election on the 25th, and the next day, Bowell’s resignation was finally accepted.[93] Tupper had less than three months to campaign before the election, and with the remedial order on hold, the impending election essentially became a referendum on the issue.

Throughout the campaign, Laurier blasted the Tupper government for not “issuing a commission to ascertain the facts of the case,” claiming it was “impossible” to deal with this question without an investigation.[94] In response, Tupper argued that notion had been “completely swept to the wind”[95] by his government. He justified the lack of an investigation, and also the Conservative’s refusal to negotiate with Greenway directly, by arguing Manitoba had forfeited its exclusive jurisdiction over education when it “legislated to take away the rights or privileges enjoyed by the minority as they had existed”[96] before 1890. On 14 April, Laurier promised that “if the People of Canada, carry me to power … I will settle this question to the satisfaction of all the parties interested … I assure you that I will succeed in satisfying those who suffer at present,”[97] and carry Laurier they did. While Tupper put together a remarkably strong campaign and even managed to claw back enough of the electorate to win the popular vote 46 to 45 percent,[98] the damage had already been done. Laurier easily won the seat count, and the election saw the Liberals achieve a swing of fifty-eight seats over the Conservatives, with Quebec carrying the election by “giving sixteen seats to the bishops” and the other “forty-nine to Laurier.”[99]

With the election finally out of the way, Laurier wasted no time in reaching out to Greenway, and over the summer and fall of 1896 the two sides negotiated a compromise. When the provincial and federal governments finally agreed to the Laurier-Greenway Compromise on 16 November 1896, the political hotbed surrounding the Manitoba School Question came to a rather abrupt end. Among several other things, the Compromise “contained a provision allowing instruction in a language other than English in bilingual schools” where enough students spoke the language, allowed Catholic teachers to be employed in schools with at least forty Catholic children, and allowed religious instruction for the last half hour of each day.[100]

Historical Significance:

For all the trouble it had caused Canadian politicians, the controversy surrounding the Manitoba School Question was all but settled by the end of the year. The Compromise did little to satisfy Catholics in Manitoba and to even get the Catholic Church to accept the Compromise, Laurier had to first appeal to the Pope. However, as far as the rest of the country was concerned, the Manitoba School Question had been answered. What officially began in 1890 as a provincial issue over education and taxation bylaws soon evolved into a fierce debate over the role that the majority and minority, the Protestant and the Catholic, and the Anglophone and the Francophone would each play in Canada’s future. It was a debate that was just as much about the future status of language, religion, and culture as it was about education and one just as much about the constitutional relationship between the provincial and federal levels of government as it was about the relationship between Manitoban Roman Catholics and Protestants.

The influence that the Manitoba School Question had on Canadian politics during the 1890s is rivalled by only a handful of issues in Canadian history. It defined the politics of Manitoba throughout the decade, and as early as 1893, it had become the most pressing political concern in the country. Politically, the Manitoba School Question and the election it defined marked a significant crossroads in Canadian history. Disagreements over how to respond to the Question caused the Conservative Party to internally split in two, especially after the death of John A. Macdonald left the party without a clear leader for the first time in decades. It impacted the political careers of countless politicians, including at least two provincial premiers and five Prime Ministers, and it gave birth to the mandates of Tupper, Bowell, and Laurier, while also ending the mandates of the first two. Laurier’s victory in the 1896 election conclusively ended the Macdonald era and the Conservative Party dominance that had defined Canada for much of its early history. It also marked the beginning of a new era, one defined by Laurier’s record of fifteen consecutive years holding the office of the Prime Minister. The “Sunny Way” promised by Laurier in 1895 and 1896 and implemented throughout negotiations for the Laurier-Greenway Compromise was, in many ways, an early glimpse into what this time in office would look like, and Tupper’s inability to regain Canada’s confidence in the election of 1900 paved the way for Robert Borden to become the leader of the Conservative Party in 1901.

It also had a significant impact on the provincial level: in Manitoba, English soon became the official language of the province with 1899’s Manitoba Language Act, and the already diminishing presence of dedicated French-language education all but vanished in the province as a result. With the national focus being placed on Manitoba for the better part of a decade, the School Question perhaps represents the province at its most relevant to national politics, and this relevance indicated the increasingly important role the Prairies would play for the next thirty-odd years as it became one of Canada’s fastest-growing regions. The concessions made in the Laurier-Greenway Compromise eventually resurfaced in the Manitoba provincial election of 1900, as the Compromise’s unpopularity was among the many reasons that Greenway was voted out. The failure of the Compromise to provide a viable framework for minority education in other provinces, in conjunction with Laurier’s unwillingness to take a firm stance on the matter, had repercussions that lasted for decades and affected several provinces. The issues of education funding, control over curriculum, and segregation of schools for religious and linguistic minorities resurfaced less than a decade later, first in the negotiations for founding Alberta and Saskatchewan in 1905,[101] again in 1911 with Ontario’s Regulation 17, and finally in 1916 when the Manitoba School Question resurfaced for the second -but arguably not final- time under future Prime Minister Borden.[102]

Conclusion:

The political contexts that made the Manitoba School Question relevant in the 1890s inevitably faded with time, and in retrospect, the situation pales in severity to many of the other crises Canadian Prime Ministers have faced that are covered elsewhere in this textbook, including the related Conscription Crisis covered by Stephen Lylyk. Indeed, the Manitoba School Question was not the first political crisis to prematurely end a Prime Minister’s career or dominate an election. It was not the first to deal with the growing divides within Canada: between French and English, Protestant and Catholic, ‘West’ and ‘East,’ and provincial and federal government. It was not the first issue related to linguistic and education rights, or even with the French in Manitoba alone. Nor would it be the last — or the most significant — instance of these issues challenging Canadian Prime Ministers. For these reasons and more, while the Manitoba School Question attracted “considerable attention” from Canadian historians in the first half of the twentieth century, the subject has been mostly overlooked over the last fifty years. However, the Manitoba School Question was unique in that it was essentially the first to encapsulate nearly all of these topics — which together account for many of the biggest political challenges in Canadian history — in a single political controversy. It was also the first, and to date, the only federal election predicated on a court decision, and this decision not only “vindicated [the Supreme Court] as a truly impartial court of justice”[103] but set a precedent for the future of provincial-federal relations. In this way, the Manitoba School Question and the 1896 election marked a significant moment in Canadian history and served as a precursor for many of the religious, linguistic, and cultural divides that would define Canada in the twentieth century. It is also a reminder of what a single individual who is willing to compromise can accomplish, of the ramifications such compromises can have, and perhaps that is what makes the Manitoba Schools crisis still worth studying today.

- Alan H. Child, “The Board of Education, Joseph Martin, and the Origins of the Manitoba School Question: A Footnote,” Canadian Journal of Education Vol. 2, no. 3 (1977), 37. ↵

- “Official Language Act (1890).” Compendium of Language Management in Canada. University of Ottawa. https://www.uottawa.ca/clmc/official-language-act-1890. ↵

- Jamie Bradburn. “‘Try the sunny way’: How Laurier and the Liberals ended 18 years of Conservative rule.” TVOntario Today. September 9, 2021. ↵

- A.B. Bethune, “Is Manitoba Right?” A Question of Ethics, Politics, Facts, and Law. A Complete Historical and Controversial Review of the Manitoba School Question. (Winnipeg, Manitoba: Tyre Bros Printers, May 18, 1896). 18. ↵

- Child, 1. ↵

- Nelson Wiseman. “The Questionable Relevance of the Constitution in Advancing Minority Cultural Rights in Manitoba.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 25, no. 4 (1992): 700. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3229684. ↵

- Ibid., 701. ↵

- Ibid., 705. ↵

- Ibid., 701. ↵

- Christopher Hackett, The Anglo-Protestant Churches of Manitoba and the Manitoba School Question. (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 1988), 4. ↵

- Wiseman, 700. ↵

- Bill Waiser, “Teaching the West and Confederation: A Saskatchewan Perspective.” The Canadian Historical Review 98, no. 4 (2017): 756. ↵

- Wiseman, 700. ↵

- J.R Miller, “D’Alton McCarthy, Equal Rights, and the Origins of the Manitoba School Question.” The Canadian Historical Review 54, no. 4, (December 1973), 381. ↵

- Wiseman, 698-700. ↵

- Waiser, 753. ↵

- [17] Ibid., 757. ↵

- Wiseman, 699. ↵

- Miller, “D’Alton McCarthy, Equal Rights, and the Origins of the Manitoba School Question,” 385. ↵

- Hackett, 10. ↵

- Ibid., 150. ↵

- J.E. Rea, “Greenway, Thomas,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 13. (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/greenway_thomas_13E.html ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Child, 39. ↵

- Ibid., 38. ↵

- Ibid., 41. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- D.J. Hall, Clifford Sifton, Volume 1: The Young Napoleon, 1861-1900. (Vancouver, CA: UBC Press, 1981), 42. ↵

- Child, 38. ↵

- Ibid., 41. ↵

- Hackett, 9. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Child, 58. ↵

- Hackett, 10, ↵

- Wiseman, 699. ↵

- Hackett, 12. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Richard A. Olmsted, Decisions of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Relating to the British North America Act, 1867 and the Canadian Constitution 1867-1954, Vol. 1, Ottawa, Department of Justice, 1954, 739p., pp. 272. ↵

- Hackett, 10-1. ↵

- Ibid., 48. ↵

- Wiseman, 697. ↵

- Ibid., 14. ↵

- House of Commons Debates: Speech of Mr. D'Alton McCarthy, M.P., on the Manitoba school question. 7th Parl, 5th Sess, Wednesday, 16 July, 1895. CIHM/ICMH microfiche series; no. 33947, 1. ↵

- Ibid., 39. ↵

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates: Speech of Mr. Laurier, M.P., on Separate Schools in Manitoba. 7th Parl, 1st Sess, (Ottawa: Printer S.E. Dawson, Wednesday, 8th March 1893). CIHM/ICMH microfiche series; no. 46308., 12 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Child, 37. ↵

- House of Commons Debates: Speech of Mr. D'Alton McCarthy, M.P., on the Manitoba School Question, 2. ↵

- Child, 58. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Gordon Bale, “Law, Politics and the Manitoba School Question: Supreme Court and Privy Council, 1985,” Canadian Bar Review 63-3 (Sept. 1985). 476 ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 479-84. ↵

- Ibid., 493 ↵

- Carman Miller, “Abbott, Sir John Joseph Caldwell,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12. (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/abbott_john_joseph_caldwell_12E.html. ↵

- P. B. Waite, “Thompson, Sir John Sparrow David,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 12. (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Hackett, 14. ↵

- “The Manitoba School Question.” The Ottawa World, November 28th, 1892. 2. ↵

- Bale, 485-97. ↵

- Wiseman, 697. ↵

- Ibid., 704. ↵

- Bethune, 19. ↵

- Canada, Parliament, House of Commons Debates: Speech of Mr. Laurier, M.P., on Separate Schools in Manitoba. 7th Parl, 1st Sess, (Ottawa: Printer S.E. Dawson, Wednesday, 8th March 1893). CIHM/ICMH microfiche series; no. 46308., 12 ↵

- House of Commons Debates: Speech of Mr. Laurier, M.P., on Separate Schools in Manitoba, 1-3. ↵

- Ibid., 59. ↵

- Ibid., 3. ↵

- Ibid., 9. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., 13. ↵

- House of Commons Debates: Speech of Mr. Laurier, M.P., on Separate Schools in Manitoba, 3. ↵

- Ibid., 10-1. ↵

- Ibid., 4. ↵

- Ibid., 12. ↵

- Ibid.,11. ↵

- House of Commons Debates: Speech of Mr. Laurier, M.P., on Separate Schools in Manitoba, 14. ↵

- Phillip Buckner, “Tupper, Sir Charles,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, (University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003), accessed April 3rd, 2023. ↵

- Bale, 503. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Opinions of Liberal members on Manitoba School Bill: from "Hansard" of 1896. Canadiana CIHM/ICMH microfiche series no. 11437. http://online.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.11437. 2-4. ↵

- Waite, “Bowell, Sir Mackenzie.” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.” Accessed April 10, 2023. http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/bowell_mackenzie_14E.html. ↵

- Buckner. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Bradburn. ↵

- Nelle Oosterom, “A Day For Laurier,” Canada's History. September 12, 2016. ↵

- Arthur Milnes, "Wilfrid Laurier: “The Sunny Way” Speech, 1895." The Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Canada. Article published July 12, 2017; Last edited July 12, 2017. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Wiseman, 704. ↵

- Buckner. ↵

- Bradburn. ↵

- Buckner. ↵

- Speech of Sir Charles Tupper, M.P., on the Winnipeg Negotiations. (7th Parl, 6th Sess, 14th April, 1896). CIHM/ICMH microfiche series; no. 900562, 8 https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.46308/1 ↵

- Ibid., 2. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Bruce Cherney, Bruce. "Manitoba School Question - Controversy Threatened to Tear Nation Apart,” Winnipeg Regional Real Estate News. March 30, 2007, https://www.winnipegregionalrealestatenews.com/publications/real-estate-news/616. ↵

- Buckner. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- “Laurier-Greenway Compromise.” Compendium of Language Management in Canada, University of Ottawa. https://www.uottawa.ca/clmc/laurier-greenway-compromise-1896. ↵

- “Language Debate Rages On.” The Daily Herald, November 4, 1905, 2. ↵

- Hackett, 16. ↵

- Bale, 518. ↵