9 Terrorism in Canada: An Analysis of Pierre Trudeau’s Response to the FLQ and the 1970 October Crisis

Kara Sirke

Introduction

Tension and unease were words commonly used to summarize the experience of Canadians, and, indeed, citizens throughout much of the Western world, as they struggled during an era of social change in the 1960s.[1] In a period of sustained economic growth that had marked much of the world since the end of the Second World War, violence became the norm as marginalized groups protested for equality, basic freedoms, and their rightful place alongside the majority. It was a period of decolonization, especially in the developing world as citizens fought to remove imperial powers from their homelands. Canada was not immune to the social unrest and the violence that often accompanied the demand for radical change. Much of the tension and social unrest in Canada centered on a minority of Québécois who had grown increasingly frustrated with their English-speaking counterparts who, for decades, dominated the political, economic, and social spheres of the province of Quebec. The history of struggle between the French and English-speaking nations is older than Canada itself, and by the 1960s it appeared to some Quebec extremists that all previous attempts at establishing greater autonomy within the confines of the Canadian democratic system, had failed. In 1963 an extremist guerilla group, the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) was founded, and its members vowed to end the marginal and disadvantaged status of French-speaking Québécois. The aim of the FLQ was a separate Quebec state, and the means required to achieve its goal were violence and terror.[2] It was a development that shook the very foundations of Canada.

With a terrorist presence threatening Canadian democracy, it was the role of the federal government to preserve the democratic system and bring order to the social unrest. Moreover, the federal government had a duty to preserve the rights and freedoms of all Canadians.[3] In 1968, towards the end of what had been a tumultuous decade, Canada elected Pierre Elliott Trudeau, a new prime minister. Trudeau envisioned a Canada that rejected the negative consequences of ethnic nationalism, and he embraced a culture of bilingualism and multiculturalism that recognized and promoted the inclusion of all of Canada’s ethnic communities. He was also a champion of all forms of individual rights.[4] The new prime minister mixed his concerns with rights and freedom with a charisma that gave him celebrity status and led him to the first majority government in Canada since 1958. He came to office with a knowledgeable perception of the separatist crisis in Quebec and was prepared to bring his vision of Canada to fruition for the betterment of all Canadians, including the Québécois.[5] But, in 1970, a tragedy, now known as the October Crisis, shocked the nation and tested Trudeau’s vision of a united Canada.

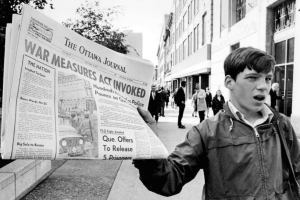

In early October 1970, two separate FLQ cells turned from violence through bombings and robberies to the kidnappings of political dignitaries, namely James Cross, British Trade Commissioner, and Pierre Laporte, Quebec Deputy-Premier and Minister of Labour. With the lives of Cross and Laporte in jeopardy, and with the fear of further kidnappings and violence, Trudeau and his cabinet faced a threat unlike anything before it in Canada.[6] This essay is an analysis of Trudeau’s discourse and actions throughout the October Crisis, and it explores how his policies demonstrated the necessity to protect the parliamentary and democratic system and maintain a united front against the threat of insurrection. Trudeau rejected the FLQ’s demands for a separate nation in Quebec; in his vision of Canada, there was no place for revolutionaries. Trudeau fought to protect Canadians’ right to safety and individual freedom through a strict policy of determined state action. The escalation of violence by the FLQ, coupled with the threat of insurrection, forced Trudeau to deploy the army and invoke the War Measures Act, emergency legislation never before used during times of peace. Ultimately, Trudeau’s actions were successful for his policies permanently nullified the FLQ threat, and he successfully achieved his objective of keeping the democratic system intact and Canada united.

Circumstances Prior to the 1970 October Crisis

The October Crisis did not occur in a vacuum; its origins can be traced to the Quiet Revolution, a period of great social and political change that occurred in Quebec during the 1960s. The period for change was reflected in the Liberal Party of Quebec’s rallying cry, maîtres chez nous, or “masters in our own home.” Elected in 1960, the Liberal Party of Quebec replaced the earlier government of former Union Nationale leader Maurice Duplessis. Under the leadership of Premier Jean Lesage, the Liberals supported numerous social movements, such as student activism and feminist and gay rights, and made major reforms in social and economic policy.[7] In the 1960s, Francophones took control of their own affairs. The Quebec dream of “two equal collectivities” (English-speaking Canada and French-speaking Quebec) and the promotion of Quebec nationalism and patriotism became main objectives of the Quiet Revolution. There emerged the belief that social change led by Quebecers and control by French-speaking Quebecers over their own affairs in all spheres of government, economy, and society was possible only if the province had greater autonomy.[8] In essence, Quebec saw Canada as dual nations, one French-speaking and the other English-speaking, and one whereby the Francophone population in Quebec would enjoy greater autonomy. The Quiet Revolution was a manifestation of Québécois nationalism and while some supported the incremental, democratic approach to achieving greater control of its affairs, others believed that such a process was too slow and wanted to accelerate Quebec’s new sense of nation.[9]

Quebec’s dream of an autonomous nation also inspired the formation of separatist groups committed to an extreme version of Quebec nationalism. The most vocal and dedicated to that version was the terrorist group known as the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ). Founded in 1963, the FLQ and its members fought for reform and a separate Quebec. While once believed to have been connected to international Marxist or socialist factions, the FLQ had few such connections and had uniquely emerged from within the social and political environment of Quebec. Its members shared a distinct vision of a Quebec worker’s state and sought to preserve French culture and language.[10]

What made the FLQ volatile was its membership structure and methods of promoting its objectives. It was comprised of various radical cells and by members that joined and left at random (often due to prison sentences for their criminal activity) and worked in secret and independently to achieve its different objectives.[11] The fluid movement of members and secrecy left authorities speculating about the actual size of membership of the FLQ. During the 16 October 1970 House of Commons debate, while the Crisis was ongoing, several ministers argued the FLQ was a small group of a few dozen, while others speculated a much greater membership of three thousand or more.[12] And who were these members? New Democratic leader, Tommy Douglas argued its membership was of the “disadvantaged” and “unfortunate” in Quebec, but Quebec MP and Social Credit leader, Real Caouette, disagreed with that interpretation. He insisted that FLQ membership was mostly from the educated middle-class.[13] Between 1963, when it was formed, and the October Crisis of 1970, the FLQ’s revolutionary actions in public escalated and were often unpredictable. Banks were common targets of armed robberies as well as assaults on buildings that the FLQ claimed symbolized Francophone oppression. In fact, the FLQ bombed and torched two hundred buildings during this period,[14] including the Montreal Stock Exchange in February 1969 in an attack that injured twenty-seven people. It had been the ninth bombing incident that year.[15] The FLQ did not only cause injuries. In the seven years between 1963 and 1970, five innocent people were killed by FLQ bombings.[16] As the decade progressed and FLQ violence became more severe and sporadic, a state of paranoia emerged amongst the people of Quebec who did not know what might happen next.

It was into this unstable political environment that Canada elected the stylish and captivating, Pierre Elliott Trudeau. Born in Montreal on 18 October 1919, Trudeau inherited both French-Canadian and Scottish lineage. He studied law at l’Université de Montréal, political economy at Harvard University, and he continued his education in schools in both Paris and London. Self-identifying as “citizen of the world”, Trudeau’s travels gained him a special appreciation and global identity, however, it perhaps negatively impacted his identification with both his English and French roots. His bilingualism would aid him in his career in politics, however, his allegiance to the Francophone culture was always tainted by his English Canadian heritage at home in Quebec and, as such, he never fully embraced the ideals of Quebec nationalism that were espoused by many engaged in Quiet Revolution.[17]

Trudeau held a negative opinion of traditional Quebec nationalism based on ethnicity and language, and argued that it was “unnecessary, wrong-headed, and…immoral.” He asserted that Francophone nationalism “imprisoned” French-speaking Canada from the rest of Canada and many of the nations around the globe. As a result, Trudeau was “uncomfortable” with much of French-speaking Quebec, and he viewed those who harboured a notion of Quebec independence as “politically backward.” To Trudeau, too many in Quebec were stuck in its ancien regime heritage with its anti-democratic views, authoritarian clergy, and its inability to recognize that its nationalism was dangerous and prevented Quebec from changing for the betterment of its people.[18] To Trudeau, traditional French-Canadian nationalism rejected liberal values and was “the enemy of democracy, individual rights, and social and economic justice.”[19] The best form of government, Trudeau believed, ensured its citizens personal freedom and protected the rights of all individuals. States that had embraced those ideas were said to have also embraced civic nationalism.[20] In contrast to nations that embraced a regime of rights and individual freedom, other forms of nationalism privileged collective rights, which, later in Trudeau’s career, he argued created a hierarchy of citizens based on characteristics such as race and language.[21] Those were values associated with ethnic nationalism, and Trudeau believed that the promotion of ethnic nationalism, or one collectivity over another, would create an unequal society, as it favored and prioritized certain groups within that society to the exclusion of others.[22] Finally, Trudeau argued that ethnic nationalism often led to war and governments based on that form of nationalism based its decisions on emotion and prejudice rather than logic and reason.[23]

Trudeau valued reason as the foundation for politics and offered federalism as a superior alternative to nationalism. Nationalism works to divide, he insisted, whereas federalism, with its divided jurisdiction between two orders of governments, functions to unite both levels of government to maintain the integrity and independence of both federal and provincial governments.[24] Trudeau argued that the unemotional dimensions of federalism made it the more inclusive and harmonious option for any state, especially those that were ethnically diverse.[25] Additionally, Trudeau valued federalism as he argued its division of powers was well-suited in Canada’s diverse, multiethnic society. Trudeau envisioned a federalized Canada that was “balanced”, neither predominately centralized nor decentralized, but a system that promoted the well-being of its workers and all citizens.[26] Trudeau’s sense of nation was one that was united and equal. No ethnicity or group was above another or received special autonomy or special status. As a result, Trudeau vehemently opposed Quebec separatism and the idea of Canada as two-nations. In the case of Quebec, Trudeau feared that to grant the province special jurisdiction that other provinces did not have, or to allow it sovereign status, would place minorities in a French-speaking Quebec in a difficult situation. He argued new minority problems would arise in a separate Quebec if French nationalism continued to dictate decision making and policies.[27]

Trudeau had clear hopes for the nation that elected him, however it would be a long road to achieve his goals. Trudeau’s support of federalism was central in his vision for Canada, however, for federalism to work, Trudeau theorized that all provinces must support an important role for the central government. Trudeau had the difficult task of securing the favor of many Quebecers who distrusted the federal government. Many in Quebec felt that the federal government treated the French-speaking minority as subordinate to the English population, and as a result the federal government gave English-speakers preferential treatment.[28] Moreover, with the state of nationalist fervor in 1960s Quebec, winning positive support for federalism proved to be an immense challenge for Trudeau.

The October Crisis

The October Crisis began 5 October 1970 when four FLQ members armed with guns stormed into British diplomat James Cross’s Montreal home and abducted him from his bedroom.[29] The kidnapping severely tested Trudeau’s ability to act during a national crisis, and the terror that unfolded was unlike anything ever experienced in Canada. According to The Globe and Mail, Mr. Cross was the first foreign diplomat to be kidnapped by a terrorist organization in Canada, but the twelfth in the Western Hemisphere since 4 September 1969.[30] Immediately after the kidnapping, the FLQ released its set of demands that were to be met by officials in Ottawa and Quebec City within 48-hours. The series of demands included $500,000 in gold bars, the publication of the FLQ manifesto, and the release and safe passage to Cuba or Algeria[31] of FLQ “political prisoners” detained in Canada.[32]

The initial statements by the press reported an optimistic tone by the federal government. External Affairs Minister Mitchell Sharp was the first to address the public. He announced he was “hopeful” Mr. Cross would be released safely without the government needing to make any concessions to his FLQ kidnappers.[33] Later, in Trudeau’s 1993 memoirs, Trudeau revealed a different tone when he stated the kidnapping shocked the federal government who “were badly equipped to deal”[34] with the seriousness of domestic terrorism. The abduction made clear to the government that the FLQ had changed their tactics to kidnapping, ransom, and the potential assassination of diplomats to have their demand for Quebec independence met.[35] After the kidnapping of Mr. Cross, Trudeau reiterated Mr. Sharp’s hopeful statements to the House of Commons on 6 October, but his inability to offer much in the way of details suggested his Cabinet was still coming to grips with the complexity of the situation. Trudeau admitted that the government considered a reward payment, and that he was in close contact with the Quebec Premier, Robert Bourassa, who, along with Quebec police, were handling the situation.[36] Some opposition members in Parliament argued that the federal government was too silent on the matter and should not delay,[37] however, the quiet response from the federal government in the days after Cross’s abduction suggested Trudeau and his cabinet took the matter very seriously but chose to proceed with caution. By 7 October, Trudeau made his position regarding the FLQ demands clear to the public when The Montreal Gazette publicized his statement that Ottawa would not allow a “minority group” to use violence and blackmail to force demands on the majority, and the government would not, in any way, bargain with the terrorists. Furthermore, Trudeau conceded that his decision was difficult since Mr. Cross’s life hung in the balance, but, ultimately, the government’s “commitment to society” was “greater than anything else.”[38] At this stage of the crisis, Trudeau appeared confident and hopeful that he would bring the ordeal to a swift conclusion.

The seriousness of the FLQ intentions was made more horrifyingly clear when just days later, on 10 October, Quebec’s Minister of Labour, Pierre Laporte, was abducted outside his home by a separate FLQ cell.[39] Laporte’s kidnapping heightened the gravity of the situation for it became evident that the actions of the FLQ had increased in its unpredictability and that the potential for further kidnappings of politicians and government officials was extremely likely. According to a report from The Globe and Mail, the situation for Mr. Cross and Mr. Laporte was cause for great concern. Two separate letters, secretly left by the separate groups of kidnappers, revealed what would happen to both men if the updated set of FLQ demands were not met. For Mr. Cross to be returned “safe and sound” required the “liberation of political prisoners and an “end to the massive police manhunt.” The FLQ cell that captured Mr. Laporte “insisted” they would “kill Mr. Laporte unless” the government did not accept the FLQ’s original conditions.[40] Included with the conditions was a handwritten letter from Mr. Laporte that offered a disturbing glimpse into his current state. He pleaded for a safe return home and stated each meal felt like his last but that he hoped to soon be free. He was hopeful that the government would meet the FLQ demands, and he thanked those who had “contributed to this reasonable decision” to give in to the FLQ terms for his release. If all worked out, he would be back at work tomorrow, he wrote.[41]

Even after the kidnapping of Mr. Laporte, the federal government still had no intentions to give in to the FLQ demands. On the same day the letters were found, the federal government had decided to enlist the Canadian Army to guard federal property in Ottawa and protect potential targets.[42] The need for extra protection in Ottawa coincided with the fact that cabinet ministers and Members of Parliament had returned to work after the Thanksgiving weekend.[43] While the 400 troops were used for protection, their presence on Canadian streets during a time of peace was an uncomfortable sight for many. Some felt that the troops only added to the public’s anxiety and might antagonize the FLQ, prompting them to commit more, or worse, acts of terror or harm. Trudeau responded to the increase in public tension and fear outside Parliament the following day on 13 October. CBC reporters waited for his arrival and for the perfect opportunity to probe the prime minister on his response to the crisis. This spontaneous interaction with journalists became one of Trudeau’s most defining interviews, for the chance to hear the prime minister speak frankly, without a rehearsed script, is a rare opportunity indeed.[44]

Trudeau’s words and demeanor throughout that seven-minute interview revealed a great deal about his opinion on the FLQ, the kidnappings, and his response to the terrorist threat as well as his approach to governing in a crisis. In true Trudeau fashion, he did not hold back or equivocate, but rather chose to engage in the reporter’s banter and defend Parliament’s actions to the developing state of emergency. Trudeau was presented with challenging questions and concerns, but he responded to all with a sense of confidence and fortitude that could have been interpreted as arrogance. To the reporter’s concern over a police state, Trudeau replied with “don’t be silly” and argued that the army were only there to be “agents of peace” and to free up the responsibilities of the police so that they could concentrate on locating Mr. Cross and Mr. Laporte. Trudeau appeared to have little patience for those who were opposed to the extra protective measures and referred to those worried about the army as “bleeding hearts” and “weak-kneed” who could “go on and bleed”. Trudeau believed the “natural” and most important response to terror and blackmail was to rid society of those committing that violence, and it was the government’s “duty” to “protect government officials and important people” who were being used as “tools in this blackmail.” To the reporter’s question of how far he was willing to go, he infamously replied “just watch me.” He ended the engagement in characteristic fashion: “This society must take every means at its disposal to defend itself against the emergent of a peril of power which defies the elected power of this country” and “so long as there is a power…which is challenging the elected representative of the people, I think that power must be stopped.”[45]

Trudeau would not stand for any form of violence that threatened the unity of the nation or Canada’s system of democracy. His response to the FLQ was to assure its members that he would do everything in the government’s power to stop its threat to the democratic state, for he was obligated, as prime minister, to do exactly that. The FLQ threat was not limited to Quebec, Trudeau maintained, as Canada was a united nation and any threat to its unity in any one part of Canada was a national concern. As the FLQ appeared to gain support, and with potentially an escalation of its acts of violence, Trudeau urged Canadians, including the press, to work alongside the government to put an end to this collective threat. However, as the interview described above made clear, some members of the press questioned the federal government’s approach to the crisis. Trudeau acknowledged at the end of that interview that the reporters play “devil’s advocate” and that it was one “hell of a role.” Trudeau was offended by the press’s commitment to challenge the federal government rather than support its decisions. Trudeau revealed exactly how difficult it was to manage a crisis by stumping the interviewer with the interviewer’s own questions. For example, the reporter stated his discomfort over the presence of the military and asked Trudeau if he was worried that the army was not large enough to protect everyone and would only cause more harm in an already tense situation. Trudeau replied sarcastically with: “So what do you suggest? That we protect nobody?” This forced the reporter to rephrase his position on the matter. Furthermore, Trudeau argued that it was the press who had judged the situation incorrectly and had responded poorly, not the federal government. Trudeau stated that the goal of the FLQ was to receive publicity, and the press played a complicit role by providing it the publicity it sought. Trudeau called on the press to stop using the FLQ term, “political prisoners” and call them what they were — convicted criminals. Trudeau called them “bandits” and “outlaws,”[46] and in doing so called on the Canadian public to recognize the distinction. Throughout the interview Trudeau presented himself clearly, firmly, and without hesitation – as a determined and forceful leader. Overall, Trudeau’s language and firm approach implied that he spoke as if his audience were FLQ members, and that a clear message had been sent that the federal army would not stand down or give in to its acts of terror.[47] The interview reflected one aspect of Trudeau’s approach to managing a crisis.

Throughout the crisis, Trudeau kept in constant communication with the RCMP, Montreal police, and all levels of government in Quebec, and it was clear that not everyone agreed on the best course of action. The kidnappings had placed Trudeau in a complicated situation, for while the actions had taken place in Quebec, the kidnapping of a British diplomat made the crisis a federal issue. In his memoir, Trudeau writes “Just as our government counted on foreign governments to protect Canadian representatives when they were on their soil, it was our [federal] duty to protect their diplomats on ours.”[48] Nonetheless, Trudeau depended upon the RCMP, as it was its mandate to ensure the safety of Canada, as well as the better judgement of the Mayor of Montreal, Jean Drapeau, and Premier Bourassa to make decisions that were best for their city and province. During a crisis, it is easy to predict that consulting with this many forms of leadership may lead to confusion and even disastrous outcomes if all advice is followed. Prominent labour and political leaders, for instance, including Parti Québécois leader René Lévesque, called on Bourassa to “free the ‘political prisoners’ to save Laporte.” Mayor Jean Drapeau and Premier Bourassa recommended that all suspected FLQ members and sympathizers be detained. During a Cabinet Committee on Security and Intelligence meeting to discuss the federal government’s response, RCMP Commissioner William Higgitt stated that provincial authorities only wanted “action for the sake of action” and he suggested that no further legislation was required.[49] Based upon these very different opinions surrounding the situation and ideas for which to proceed, one leader had to take charge and make the difficult decision.

During two meetings on 15 October, Trudeau’s Cabinet was told the conditions in Montreal were dire. The Quebec government had called on the federal government to enact special legislation to deal with the ongoing crisis. Authorities knew the FLQ had in their position dynamite and explosives and, combined with the growth of public support for the FLQ and the very real threat of insurrection, time was running out for the government to act. In fact, the federal government needed to “act as soon as possible.”[50] Furthermore, Trudeau argued that the more time the federal government allowed opinion makers in Quebec to negotiate the release of FLQ prisoners, “the more we stood to lose.”[51] The release of FLQ criminals was not an option for Trudeau. In Trudeau’s 1993 memoirs he reiterated his position to never negotiate with terrorists, “not even to obtain the release of a hostage.” Trudeau explained that to do so would begin an endless chain of violence and kidnappings for it would have taught the FLQ one thing: they could continue to be arrested on acts of violence because all that was needed to be set free was to kidnap again and demand their safe release.[52] Trudeau made it clear that he would avoid insurrection at all costs, for insurrection would be the ultimate defeat of democracy and political stability, and the only way to prevent it was to act before the FLQ had a chance to succeed.[53] Trudeau and his cabinet considered and debated their special legislative options and reached a consensus that evening. All ministers agreed to invoke the War Measures Act as it was the best means to, as Trudeau explained in his memoirs, “prevent the situation from degenerating into chaos”.[54] The War Measures Act, however, would have limits in its “duration” and “scope,” and would not become official until the federal government received an authorized written request from the Quebec levels of government stating there was “no alternative” but to invoke emergency powers.[55] On 16 October, Trudeau addressed the House of Commons with the cabinet’s decision. Later that same day, Trudeau delivered a speech to the nation which explained the reasoning for the government’s decision to invoke the War Measures Act, and reminded the nation that the federal government was in charge of the situation.

The first portion of Trudeau’s speech over the entire CBC network was to deliver a clear overview of the current situation with the aim to ensure Canadians knew the facts. Until this moment, most of the information Canadians had received came through the press. Therefore, Trudeau’s speech provided the public the prime minister’s perspective. Trudeau connected to the deeper emotions and fear of Canadians and offered a national warning. He described the kidnappers as “violent and fanatical” who were “attempting to destroy the unity and freedom of Canada.” As such, Canada was in a “grave crisis” and the safe return of Mr. Cross and Mr. Laporte was of “utmost gravity” to the government. While the FLQ worked to divide Canada, Trudeau’s address to the nation worked to unite Canadians. Trudeau also hoped to dismantle any public support or sympathy for the FLQ members by presenting them as murderers, not martyrs, who were to pay for their violent crimes against democracy and the freedom of all individuals. While Trudeau described Canadians as “tolerant” and “compassionate,” the federal government was showing leadership with a firm approach to a growing crisis. Ottawa would not give in to FLQ blackmail to release criminals for if it did Canada’s legal system would “breakdown” and, Trudeau warned, would be replaced by “the law of the jungle.” Trudeau played on the public’s fear to paint a picture of a chaotic future if the FLQ were supported or were victorious, but he did acknowledge that there was work needed to fix Canada’s deeply rooted social issues. Violence, however, was not the answer to enact change. Democracy needed to be preserved, for if Canadians disagreed with its government, they were free to elect others to replace it through peaceful means. Finally, Trudeau concluded the first portion of his speech with a clear message: if harm were to come to Mr. Cross or Mr. Laporte, it would be the fault of the FLQ, not the government, and “only the most twisted form of logic could conclude otherwise.” This statement was an attempt to remind the nation that its enemies were the FLQ, not the federal government, and that the government did not stand for violence against individuals or individual liberties but acted in Canadians best interest.[56]

The final portion of the speech to the nation highlighted the seriousness of the crisis, and the government’s reasoning for invoking the War Measures Act. Trudeau used clear language to explain how the government planned to use the Act, and dramatic language to justify its necessity. Trudeau compared the armed revolutionaries to a “cancer” that needed to be destroyed to protect Canadian freedoms. Trudeau realized there would be opposition to the War Measures Act, and his attempt to deflect blame made it clear that the federal government was “reluctant” to invoke such powers. The Act was only invoked at the request of the Quebec government which made it “crystal clear” that there was no other alternative to control the situation. Trudeau acknowledged that the “strong powers” were “distasteful” but necessary to effectively prevent the “violent overthrow of [the] democratic system” by allowing the police more freedom to do their job. The government was accountable for any action taken while the Act was in place, and the legislation providing for the Act would be revoked as soon as it was deemed necessary. Trudeau called on Canadians not to become “obsessed” with the government’s decision, but to recognize that the “vicious game” was started by the revolutionaries. The government was only acting to defend a Canadian society free from hate. Finally, Trudeau presented a clear message for anyone who was still unsure about the use of emergency powers. The War Measures Act would protect the life and liberty of all Canadians and make clear to “kidnappers, revolutionaries, and assassins” that “laws are made and changed by the elected representatives of all Canadians,” not “self-selected dictators.” Trudeau’s speech ultimately presented to Canadians that their interests and freedoms were protected in its current state, and an FLQ victory would be a nightmare, for all those who gain power through terror rule through terror.[57]

On 18 October, two days after the War Measures Act was invoked, the crisis peaked after Pierre Laporte was found executed in a trunk of a car at St. Hubert Airport.[58] Trudeau addressed the nation again, only this time the tone of his speech was somber as he shared the same shock felt by all Canadians. Trudeau’s address was brief. He called Mr. Laporte’s assassins “cowards” and his death a “cruel and senseless shame” that should never have occurred. He ended with an expression of deep regret to Mr. Laporte’s family and called on all Canadians to “stick together” in this “very sorry moment in our history.”[59] The outcome of Laporte’s murder united Canadians and as a result Trudeau received significant support. Trudeau opened the 19 October House Debates with a message that the FLQ had revealed it had “no mandate but terror, no policies but violence, and no solutions but murder” and had “sown the seeds of its own destruction.” The death of Laporte would become a symbol for Canada’s “opposition to division, disunity, and hatred,” and Canadians shared “passion for justice” would bring an end to the terrorism and “find peace and freedom.”[60] While some opposition towards the use of the War Measures Act was expressed in the House of Commons, ultimately all members agreed that it was important to stand together in Canada’s time of mourning,[61] and the House of Common’s passed a motion in support of the War Measures Act.[62]

Trudeau deflected blame for any criticism the federal government received for invoking the War Measures Act on Quebec police, and alternatively argued that the federal government responded the best it could under abnormal circumstances precipitated by the crisis. By 28 October, due to the police’s power to arrest freely, almost 400 people were detained on suspicion of FLQ affiliation, and of that total number 259 were eventually released without charges.[63] In Trudeau’s 1993 memoir, he takes no responsibility for those arrests and argued it was the job of the Montreal and provincial police to properly verify its list of suspects. He acknowledged that mistakes happen, especially in a time of crisis, therefore forgiveness and understanding should be given to the police.[64] This made for a strong argument and proved Trudeau’s intentions were not dictatorial when he invoked the War Measures Act, for he allowed each branch of police the freedom to act without federal intervention. Furthermore, the federal government followed through on its promises to defend Canadians and revoked its emergency powers as soon as the crisis ended. The government, still unsure of FLQ popularity and depth at the time, introduced new legislation on 2 November 1970 when it replaced the War Measures Act with the Public Order (Temporary Measures) Act. This act came into effect 3 December 1970 and lasted until 30 April 1971 and was a more direct legislation as it dealt specifically against the FLQ.[65] In the end it was discovered that the FLQ “masterminds” reaping havoc on the state consisted of “two rag-tag gangs of radical misfits.”[66] While in hindsight this information provides strong evidence against the necessity of the War Measures Act, this was only discovered after the crisis had already reached its conclusion. Trudeau responded with the information that was provided to him and Parliament by Quebec and the RCMP. Based on that information, there was a strong argument for insurrection, therefore, the government’s decision to act quickly and invoke the Act was justified.

Just before 1970 concluded, the October Crisis came to an end. Beginning on 6 November and continuing into December 1970, the kidnappers of Mr. Cross and Mr. Laporte were arrested.[67] On 4 December James Cross was released “in good shape” in exchange for the safe passage of his three kidnappers and their four family members to Cuba which had agreed to accept them. Trudeau, however, did not grant Mr. Laporte’s murderers the same leniency.[68] Just before New Year’s Eve, those responsible for Laporte’s murder were arrested and detained in Canada bringing an official end to the Crisis.[69] The October Crisis brought Canadians together over the country’s shared mourning of Mr. Laporte’s death and over its strong support for democracy. It was clear that the anxiety and fear created by the FLQ’s actions were not limited to Quebec and Ottawa. The Regina Leader Post reported on 31 December that the abduction of Cross cast a “shadow [that] fell across all Canada” and that people from across the nation came together to share in a collective suffering. For example, during Sunday morning service at Knox United Church in the remote town of Gull Lake Saskatchewan, the congregation paused to sing O Canada in an act of public support.[70]

When the chaos ended, the country reflected upon the government’s and Trudeau’s response to the October Crisis. Public support for the War Measures Act was “powerful and immediate,” including in the Prairie Provinces.[71] A November 1970 Gallup survey found Canadians approved of the invocation of the War Measures Act to control the crisis. Worried and fearful for Mr. Cross’s safety and of a terrorist uprising,[72] an overwhelming 87 percent of Canadian’s supported the government’s use of the emergency legislation. In the same poll, 60 per cent of Canadians said that their opinion of Trudeau increased as a result of his actions and language throughout the crisis. In contrast, 49 per cent said that their opinion of opposition leader Robert Stanfield, who opposed Trudeau’s response to the crisis, declined.[73] The only individuals who seemed to oppose the Act were members of the opposition.[74] NDP leader Tommy Douglas stated the Act was akin to “using a sledgehammer to crack a peanut.”[75] Trudeau responded best to Douglas’s statement by stating in his memoir: “peanuts don’t make bombs, don’t take hostages, and don’t assassinate prisoners. And as for the sledgehammer, it was the only tool at our disposal.”[76] John Turner, the Minister of Justice from 1968 to 1972, initially contemplated the need to use the War Measures Act, and, in a private letter to a friend stated “…a threat to the very structure of society can only be met sometimes by a temporary suspension of some of the ordinary rights to which we are accustomed.” Upon reflection Turner concluded that if the government had let matters escalate with no intervention for just a few more hours that things “might have been disastrous.”[77] While hypotheticals offer little justification, what is certain is that the federal government won popular support for its actions during the October Crisis.

Conclusion

Trudeau’s disdain of nationalism and his prediction of its adverse consequences was evident during the FLQ crisis that threatened the very unity of Canada. Furthermore, Trudeau’s preference for federalism proved, in this case, to be the successful alternative of ardent nationalism. The handling of the crisis was a joint effort between the federal and Quebec governments, and Trudeau and his cabinet did not make any decision unless requested or approved first by Quebec.[78] Whether or not individuals agree with the policies Trudeau and his government followed during the October Crisis, Trudeau’s unwavering leadership and firm opposition to the crisis created by the domestic terrorism that threatened Canadian unity can be admired. While Trudeau’s value of the rights of the individual was, ironically, tested and compromised during the invoking of the War Measures Act, he assured all Canadians that the emergency powers were temporary and limited in scope. For the federal government, time was of the essence for the lives of Mr. Cross and Mr. Laporte were in jeopardy. The primary focus was the elimination of the FLQ, which had used violence for almost a decade and had proven itself an unpredictable guerilla group. Temporary emergency powers that could restrict individual freedom was a limited price to pay for eliminating further violence and possible insurrection. Trudeau’s answer to the FLQ was a defensive strategy to deploy Canadian troops and use emergency powers through the War Measures Act. The use of both measures came at a moment when all Canadians were called upon to trust that their government would not abuse its power but use it instead to protect the nation. Trudeau succeeded in doing that. Support for the FLQ, and its overall existence, ended with the invoking of the War Measures Act and after the appalling murder of Mr. Laporte. And, while Quebec separatism continues to be an ongoing discussion in Canada, violence, like that experienced at the hands of the FLQ, has not since occurred in Quebec.[79]

In a 1972 CBC interview Trudeau was asked to reflect upon his first four years as prime minister. The reporter asked Trudeau how he felt about being labelled as “arrogant” and how this label has contributed to his negative image. Trudeau considered the question carefully and replied that having a strong central government and a strong constitution was essential for Canada “to have a real existence.” Trudeau believed he had to be strong, and unfortunately sometimes that appeared as arrogance. He hoped this was not true, but if he had made mistakes, he was just an ordinary person for “no man is without sin.”[80] While judged upon his actions, Trudeau acted in the interest of Quebec, and in accordance with what he felt was best for Canada. Trudeau and his cabinet faced a crisis unique and unprecedented in Canada, and their actions sent a strong message and set a standard for dealing with future threats to Canadian democracy.

- “Pierre Trudeau’s War Measure Act Speech during the October Crisis,” CBC Archives, 1970, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1558489391. ↵

- William Tetley, The October Crisis, 1970: An Insider’s View (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007), 4. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, 4. ↵

- Robert Wright, Trudeaumania: The Ride to Power of Pierre Elliot Trudeau (Toronto: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd, 2016), xiv. ↵

- Wright, Trudeaumania, xiv. ↵

- Pierre Elliott Trudeau, Memoirs: Pierre Elliott Trudeau (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 1993), 134. ↵

- Dominique Clément, “The October Crisis of 1970: Human Rights Abuses Under the War Measures Act,” Journal of Canadian Studies 42, no. 2 (2018): 162. ↵

- Guy Laforest, Trudeau and the End of a Canadian Dream (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1993), Electronic Version, 5. ↵

- Consult Corey Safinuk’s article within this Pressbook titled “Pearson and His Response to Quebec Separatism” for more information on Quebec nationalism and the 1960s Quiet Revolution. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, 18. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, 18. ↵

- Canada, “16 October 1970,” Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada: Third Session – Twenty-eighth Parliament: Volume 1 (Library of Parliament, 1970), 199 – 201, https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.debates_HOC2803_01/. ↵

- Canada, “16 October 1970,” 200 – 201. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, xxxvi. ↵

- Special to The New York Times, "Bomb Explodes in Montreal Stock Exchange, Wounding Many," New York Times (1923-), Feb 14, 1969, 8, https://www.proquest.com/docview/118729920/EBD0683B30784617PQ/1?accountid=13480. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, XXVI & 39. ↵

- Kenneth McRoberts, Misconceiving Canada: The Struggle for National Unity (Toronto: Oxford University Press), Electronic Version, 56. ↵

- McRoberts, Misconceiving Canada, 56 – 57. ↵

- McRoberts, Misconceiving Canada, 58. ↵

- Raymond B. Blake, We Are Canadian: Prime Ministers Build Canada’s Story, From Mackenzie King to Justin Trudeau (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, Forthcoming 2023), 5. ↵

- Paul Litt, Elusive Destiny: The Political Vocation of John Napier Turner (Vancouver: UBC Press), 131. ↵

- Raymond B. Blake, We Are Canadian: Prime Ministers Build Canada’s Story, From Mackenzie King to Justin Trudeau (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, Forthcoming 2023), 5. ↵

- McRoberts, Misconceiving Canada, 59. ↵

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia, “Federalism,” Encyclopedia Britannica, February 7, 2023, https://www.britannica.com/topic/federalism. ↵

- McRoberts, Misconceiving Canada, 62. ↵

- Allen Mills, Citizen Trudeau: An Intellectual Biography, 1944 – 1965 (Toronto: Oxford University Press), 330 – 333. ↵

- Allen Mills, Citizen Trudeau: An Intellectual Biography, 1944 – 1965, 126. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, 12. ↵

- Ronald Lebel, "Ransom for Kidnapped Diplomat: FLQ Demands 0,000 in Gold, Free Prisoners, Part of Terms," Globe and Mail (1936-), Oct. 06, 1970, 1. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1242196429/2C5EE74663D3472APQ/1?accountid=13480. ↵

- Ronald Lebel, “Ransom for Kidnapped Diplomat: FLQ Demands 0,000 In Gold, Free Prisoners, Part of Terms," Globe and Mail (1936-), Oct. 06, 1970, 1. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1242196429/2C5EE74663D3472APQ/1?accountid=13480. ↵

- Cuba and Algeria had histories of class struggles against colonialism and imperialism in addition to previous accounts aiding foreign revolutionaries. The FLQ believed that either country would be sympathetic to their cause and would aid FLQ prisoners. Consult Chapter 4 and Chapter 5 of William Tetley, The October Crisis, 1970: An Insider’s View (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2007) for further history. ↵

- “Note sets 48-hour Deadline,” The Ottawa Citizen (1954-1973), Oct. 06, 1970, 1. https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/october-6-1970-page-1-56/docview/2338776826/se-2. ↵

- Greg Connolley, “Anxious MPs Grill Minister," The Ottawa Citizen (1954-1973), Oct. 06, 1970, 1. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2338776826?parentSessionId=MXtxki80eEwowCZCPSmT64+zkhMmVLKGi8ZqZfheyDA=&accountid=13480. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 134. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 134. ↵

- Canada, “6 October 1970,” Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada: Second Session – Twenty-eighth Parliament: Volume 8 (Library of Parliament, 1970), 8,801, https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.debates_HOC2802_08/1. ↵

- Canada, “6 October 1970,” Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada: Second Session – Twenty-eighth Parliament: Volume 8 (Library of Parliament, 1970), 8,801, https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.debates_HOC2802_08/1. ↵

- “October 8, 1970 (Page 8 of 40),” The Gazette (1867-2010), (Montreal, Canada), Oct 08, 1970, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2199044435/5F8BC98194E44B8PQ/1?accountid=13480. ↵

- Edward Cowan, “Asked Men Seize Quebec Official; Briton Still Held: Kidnapping Comes Minutes After Government Offer for Cross's Release Masked Men Take Quebec Minister," New York Times (1923-), Oct 11, 1970, https://www.proquest.com/docview/117862347/86C3E70E18B4513PQ/1?accountid=13480. ↵

- Ronald Lebel and Lewis Seale, “Cabinet’s Lawyer Talks to Lemieux,” Globe and Mail (1936 -) (Toronto, ON), Oct. 13, 1970, https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/cabinets-lawyer-talks-lemieux/docview/1242206893/se-2. ↵

- P.L., “Typewritten Message Sent to Station CKAC: Texts of Chenier Cell Communique and Laporte Letter to Premier of Quebec,” Globe and Mail (1936 -) (Toronto, ON), Oct. 13, 1970, https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/typewritten-message-sent-station-ckac/docview/1242212925/se-2. ↵

- Tetley, “The October Crisis,” 4. ↵

- David Crane, “Federal Ministers’ Homes Protected: Troops Called in to Guard Ottawa; Quebec Starts FLQ Negotiations RCMP Gets Help in Security Move,” Globe and Mail (1936-) (Toronto, ON), Oct. 13, 1970, https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/historical-newspapers/federal-ministers-homes-protected/docview/1242206857/se-2. ↵

- “1970: Pierre Trudeau says ‘Just watch me’ during October Crisis,” CBC Archives, 1970, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2565499342. ↵

- “1970: Pierre Trudeau says ‘Just watch me’ during October Crisis,” CBC Archives, 1970, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2565499342. ↵

- “1970: Pierre Trudeau says ‘Just watch me’ during October Crisis,” CBC Archives, 1970, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2565499342. ↵

- “1970: Pierre Trudeau says ‘Just watch me’ during October Crisis,” CBC Archives, 1970, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/2565499342. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 135. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 123. ↵

- “The FLQ Situation,” Cabinet meeting, October 15, 1970, 9:00 a.m., 4, Cabinet conclusions, LAC, RG 2, Privy Council Office, Series A-5-a, vol. 6359, http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=CabCon&id=137&lang=eng. ↵

- “The FLQ Situation,” Cabinet meeting, October 15, 1970, 9:00 a.m., 5, Cabinet conclusions, LAC, RG 2, Privy Council Office, Series A-5-a, vol. 6359, http://central.bac-lac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=CabCon&id=137&lang=eng. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 134. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 143. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 143. ↵

- “The FLQ Situation,” Cabinet meeting, October 15, 1970 (p.m. Session), 8, Cabinet conclusions, LAC, RG 2, Privy Council Office, Series A-5-a, vol. 6359, http://central.baclac.gc.ca/.redirect?app=CabCon&id=138&lang=eng. ↵

- “Pierre Trudeau’s War Measure Act Speech during the October Crisis,” CBC Archives, 1970, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1558489391. ↵

- “Pierre Trudeau’s War Measure Act Speech during the October Crisis,” CBC Archives, 1970, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1558489391. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 128. ↵

- “Pierre Laporte Crisis,” Fed Vid, March 29, 2011, video, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A-Oia6N5600. ↵

- Canada, “19 October 1970,” Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada: Third Session – Twenty-eighth Parliament: Volume 1 (Library of Parliament, 1970), 331, https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.debates_HOC2803_01/. ↵

- Canada, “19 October 1970,” Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada: Third Session – Twenty-eighth Parliament: Volume 1 (Library of Parliament, 1970), 331 – 332, https://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.debates_HOC2803_01/. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 128. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 128. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 146 – 147. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 128. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 129. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 129. ↵

- Jay Walz, “Cross Free as Kidnappers Fly to Cuba: Briton Rescued in Montreal After being Held for 59 Days,” New York Times (1923 -), (New York, N.Y.), Dec 04, 1970, https://www.proquest.com/docview/118971488/7A9916903B79495CPQ/1?accountid=13480. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 129. ↵

- “December 31, 1970 (Page 8 of 32),” The Leader Post (1930 – 2010), (Regina, Saskatchewan), Dec 31, 1970, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2217854742?parentSessionId=9SH8gWvm3CZM2juDk08JiP8Js/b8qNerXIFgfI755g4=&accountid=13480. ↵

- “December 31, 1970 (Page 8 of 32),” The Leader Post (1930 – 2010), (Regina, Saskatchewan), Dec 31, 1970, https://www.proquest.com/docview/2217854742?parentSessionId=9SH8gWvm3CZM2juDk08JiP8Js/b8qNerXIFgfI755g4=&accountid=13480. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 128. ↵

- Gallup Canada, 2019, “Canadian Gallup Poll, November 1970, #344”, Borealis, V1, https://doi.org/10.5683/SP2/IWGCOC. ↵

- “December 31, 1970 (Page 8 of 32),” The Leader Post (1930 – 2010), (Regina, Saskatchewan), Dec 31, 1970. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2217854742?parentSessionId=9SH8gWvm3CZM2juDk08JiP8Js/b8qNerXIFgfI755g4=&accountid=13480 ↵

- Canada, “16 October 1970,” Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada: Third Session – Twenty-eighth Parliament: Volume 1 (Library of Parliament, 1970), 198. ↵

- Trudeau, Memoirs, 143. ↵

- Litt, Elusive Destiny, 130. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, 188. ↵

- Tetley, The October Crisis, 188. ↵

- “A 1972 CBC Weekend Interview with Pierre Trudeau,” CBC Archives, 1972, video, https://www.cbc.ca/player/play/1844713021. ↵