1 “To Convince the Red Man that the White Man Governs:” John A. Macdonald and Canadian Indian Policy in the North-West

Jack J. Nestor

Introduction

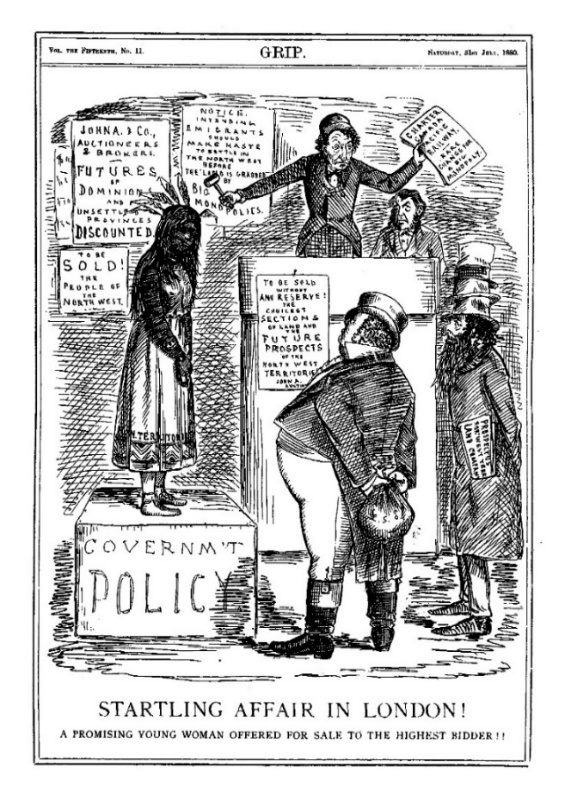

The prevailing historiography of Canadian Indian policy in the North-West posits that its architects endeavoured to assimilate First Nations into Canadian society.[1] As Minister of the Interior and Superintendent-General of Indian Affairs for much of the period after the Dominion of Canada’s acquisition of the North-West in 1869, Prime Minister John A. Macdonald has figured prominently in this historiography. Buttressed by myriad distortions of the historical record, strict fidelity to Macdonald’s public rhetoric and legislative articulation in crafting Indian policy in the North-West has produced the conclusion that, despite its failures, Indian policy in the region was well-intentioned.[2] However, Macdonald’s private correspondence with Dominion officials in the North-West, and the behaviour of Indian policy administrators at Macdonald’s behest, prior to, amidst, and after the North-West Resistance of 1885 undermine this conclusion. Rather than seeking to assimilate the First Nations of the North-West, Macdonald, together with subordinate policy architects, and Department of the Interior/Department of Indian Affairs employees manipulated the political climate of the North-West to foster and maintain the subjugation of First Nations, and thus ensure the certainty of Canadian sovereignty in the region.

Perhaps the most flagrant distortion of the historical record is that the Dominion applied the same Indian policy that existed in Central and Eastern Canada to the context of the North-West.[3] Although widely accepted in the existing historiography, this assertion fails to account for the unique circumstances which prevailed in the North-West upon and after the Dominion of Canada’s purchase thereof in 1869.[4] It became immediately apparent that the First Nations population in the North-West was both more numerous and more powerful than Dominion officials initially believed. The lowest population estimate of the North-West during the treaty-making period (1871-1877) was provided by the Oblate Father Albert Lacombe in 1875 at 9,340.[5] When settlers endeavoured to encroach upon Indigenous territory in Manitoba, a band of Saulteaux under Yellow Quill forcibly prevented their advance west of Portage la Prairie and warned them not to harvest firewood until a treaty was negotiated.[6] The repelling of Canadian immigrants (and Dominion survey and telegraph line crews) was observed by the non-Indigenous population as an existential threat to the Dominion in the North-West.[7] Thus, missionaries, traders, and Dominion officials in the North-West lobbied aggressively for treaty negotiations—frequently with the understanding that the First Nations desire for treaty was precarious so long as they remained dominant in the territory.[8]

It is difficult to overstate the dominance of First Nations in the North-West. Indeed, the historical record demonstrates that First Nations were sufficiently obstructive to cast the Dominion’s acquisition of the North-West into doubt.[9] In 1873, Lieutenant-Governor Alexander Morris reported a population of 140,000 west of Fort Ellice could field a force of 5,000 warriors armed with repeating rifles.[10] In the same year, the military force at Fort Garry numbered only 72, and isolated from reinforcements in Central Canada, were as Patrick Robertson-Ross said of the Saskatchewan territory, “living by sufferance, as it were, entirely at the mercy of the Indians.”[11] The mobilization of the North-West Mounted Police (NWMP) in warfare against First Nations would have undermined the nature of their role without substantially altering the balance of power given that the number of enlisted men and officers plateaued at 500 in 1886.[12] Further, while the United States was spending $20 million annually on Indian wars the Dominion budget was $19 million.[13] Only after it was made apparent that the Dominion could not militarily subdue the First Nations of the North-West did it concede that “it is better to feed than to fight them.”[14] The dominance of First Nations in the North-West—in conjunction with the economic duress confronting the Dominion—allowed First Nations to wield substantial power in the negotiations of seven Numbered Treaties between 1871 and 1877.[15]

The principal objective of First Nations negotiators was to secure their futures in the face of rapidly declining bison herds. However, that the dominance of First Nations in the North-West was shattered with the demise of the bison herds in 1878-79 constitutes another perversion of the historical record.[16] To be sure, the collapse of the staple of Plains First Nations’ economies provoked a crisis among these peoples. By November 1878 so destitute were First Nations that many had resorted to eating their own dogs when denied access to rations.[17] Prior to 1878 and the return of the Macdonald Liberal-Conservatives, Allan McDonald and M.G. Dickieson were effectively the only distributors of relief in the North-West superintendency—comprising some 206,000 square miles.[18] Dickieson admitted that to properly assist First Nations, the Dominion would have to go beyond the terms of the treaty in recognition that “we are on the eve of an Indian outbreak which will be caused principally by starvation.”[19]

The suggestion by Dickieson, although made to the outgoing Alexander Mackenzie Liberals, did not accord with the ambitions of the incoming Macdonald Liberal-Conservatives. It is therefore unsurprising that Dickieson left the Department of the Interior shortly after the appointment of Edgar Dewdney as Indian Commissioner in May 1879.[20] By the time of Dewdney’s appointment, the Interior portfolio was deemed of such significance that Macdonald assumed the position himself.[21] The importance of the Interior portfolio is explained by Macdonald’s National Policy which required docility in the North-West to facilitate the construction of the Canadian Pacific Railway mainline and to encourage agricultural settlement near the mainline.[22] Accordingly, the Numbered Treaties were reconfigured by Macdonald and Dewdney as instruments to control obstructive elements. First Nations that persisted outside of the treaty relationship, beyond the reach of Macdonald and Dewdney, needed to be brought into treaty and therefore under control. To accomplish this subjugation, Macdonald and Dewdney operated in concert to weaponize the distribution of relief.[23]

From the perspective of Macdonald and Dewdney, the principal agitators in the North-West were Big Bear, Piapot, and Little Pine whose collective band membership composed more than half of the entire First Nations population in Treaties 4 and 6.[24] All three leaders had refused to take treaty at the initial negotiations in 1874 and 1876.[25] Consequently, when the Dominion failed to uphold its obligations towards its treaty partners and starvation set in, the popularity of Big Bear, Piapot, and Little Pine grew substantially.[26] As swiftly as First Nations support coalesced around the leaders, Dewdney’s announcement that only First Nations who had taken treaty would be eligible for rations served to erode this support once the Plains Cree were denied access to the dwindling bison herds.[27] Additionally, Dewdney’s initiative to acknowledge any man that could procure the support of 100 followers as a chief damaged the authority of the holdouts from treaty as band members formed their own bands or joined others under treaty.[28]

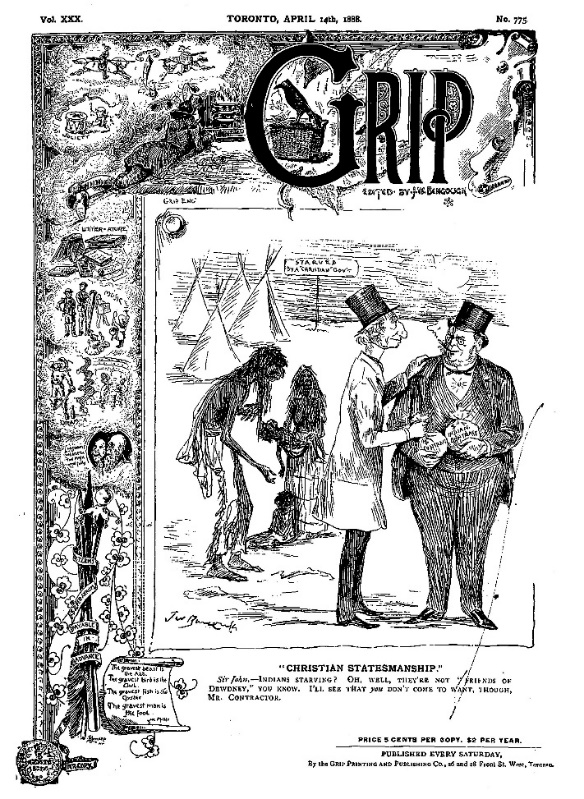

In 1882, a year after Dewdney became Lieutenant-Governor, all three leaders had been brought under treaty.[29] The taking of treaty by Big Bear, Piapot, and Little Pine did not end the agitating by the Plains Cree leadership or the weaponization of food to quell this agitation. Ostensibly to rationalize liberal expenditures amidst heavy criticisms, Macdonald explained in the House of Commons on 27 April 1882 that, “the agents as a whole, and I am sure it is the case with the Commissioner, are doing all they can, by refusing food until the Indians are on the verge of starvation, to reduce the expense.”[30]

Donald B. Smith has cited Macdonald’s explanation of rationing as proof of the goodwill which he exhibited towards First Nations by placing it in the context of Liberal accusations of financial mismanagement.[31] Absent from Smith’s argument are the dishonesty of ration supply contracts and the deliberate withholding of rations. When the deaths of members of an Assiniboine band were caused by poor quality rations, Macdonald responded to Liberal claims that the Government and First Nations were being defrauded by stating, “[i]t cannot be considered a fraud on the Indians because they were living on Dominion charity… and, as the old adage says, beggars should not be choosers.”[32] Erstwhile, rations were known to have gone to waste when employees in the service of the Department of Indian Affairs refused to issue them.[33] Adherence to a strict work-for-rations policy also encouraged instances of violence.

Perhaps the most infamous incident occurred in the Crooked Lakes Agency which demonstrated the prevailing weakness of the Dominion in the North-West.[34] Farm instructor Hilton Keith—who replaced James Setter in 1883 after the latter’s failure to conform to rationing policy—proved willing to uphold the rationing policy of the Department of Indian Affairs even during instances of widespread starvation.[35] Consequently, on 18 February 1884, when Keith refused rations to starving Plains Cree at the storehouse on the Sakimay Reserve, a group of 25 armed warriors under the leadership of Yellow Calf seized the storehouse and distributed rations amongst themselves.[36] The inability of the NWMP to make arrests on the Sakimay Reserve required Assistant Indian Commissioner Hayter Reed to negotiate a settlement to the issue.[37] In exchange for the evacuation of the storehouse, Reed agreed to increase rations—a radical departure from the behaviour which had earned him the moniker “Iron Heart” among the First Nations of the Battleford region.[38]

In explaining this course of action to his superiors, Reed reported that the First Nations were aware of the power they wielded in the region. More particularly, Reed observed that First Nations “knew that the White mans (sic) iron horse is useless when the rails on which it travels have been torn up.”[39] Thus, the decline of the bison failed to affect the reversal of the power dynamics of the North-West in the Dominion’s favour. On the contrary, incited by the Dominion’s attempts to manufacture this reversal, the desperation of First Nations encouraged greater willingness to exert their power in pursuit of securing themselves against privation. Until an opportunity presented itself to shatter the power of First Nations in the North-West, Indian policy reverted to avoiding a costly and cataclysmic Indian war.[40]

While Dewdney moved earnestly to placate First Nations in the North-West, the arrival of Louis Riel in July 1884 threatened to undermine Dewdney’s efforts. The attendance of Riel at the Duck Lake council later that month had convinced Dewdney and other authorities in the North-West that Riel was seeking to encourage the prospect of an uprising among the First Nations.[41] Although Reed issued a public statement declaring that the potential of an Indian war was limited, Dewdney expressed great fear to Macdonald—and David McPherson who had assumed de jure responsibility for the Interior profile in 1883—and officials in the North-West over the severity of the situation.[42] To ascertain the possibility of a joint First Nations-Métis uprising, Dewdney and Reed canvassed opinion among the Plains Cree.[43] The information gathered by Dewdney and Reed did much to relieve anxieties as it demonstrated the minimal influence which Riel enjoyed amongst the First Nations.[44] However, Dewdney and Reed became acutely aware of a growing campaign among the Plains Cree—who were now making overtures to the Blackfoot Confederacy—to renegotiate the treaties.[45] The power that a Plains Cree-Blackfoot Confederacy general alliance could exert would render Dominion control of the region untenable.[46] Thus, architects of Indian policy moved to implicate First Nations leadership in the impending North-West Resistance in order to stem their diplomatic initiatives.

In reality, officials in the Department of Indian Affairs had been attempting to discredit the leaders of these initiatives prior to the outbreak of violence in the spring of 1885. As early as 1879, rumours circulated of an alliance between Big Bear and the militant Sioux chief Sitting Bull, demonstrating to Dewdney the importance of limiting Big Bear’s influence.[47] Accordingly, Big Bear was swiftly labelled as both troublesome and dangerous by the Department of Indian Affairs.[48] Within his band, Big Bear’s influence was waning as support for the more assertive tactics of the war chief Wandering Spirit blossomed.[49] On 1 April 1885, Wandering Spirit assumed control of the band and took hostages from Frog Lake and the surrounding area after the refusal of Indian Agent Thomas Quinn to issue rations.[50] The circumstances of the situation at Frog Lake paralleled that at the Sakimay Reserve in the previous year. However, when Quinn—at this point a prisoner of Wandering Spirit—stubbornly refused to comply with the orders of Wandering Spirit, he provoked an outbreak of violence which left himself and eight others dead.[51]

According to Blair Stonechild and Bill Waiser, the Frog Lake Massacre was undertaken independently of the Métis.[52] However, they concede that Métis agitators had encouraged the resorting to violence.[53] Regardless of the degree to which Métis influence had contributed to the violence, the Frog Lake Massacre was carried out in retaliation for grievances independent of the Métis cause.[54] Nonetheless, the temporal proximity of the massacre to the Métis victory at Duck Lake on 26 March 1885 allowed both architects of Indian policy and the press (most notably P.G. Laurie’s Saskatchewan Herald) in the North-West to establish a link between the actions of Wandering Spirit’s band and that of Riel’s Adjutant-General Gabriel Dumont.[55]

A connection between the actions of the Métis and Poundmaker’s band of Plains Cree-Assiniboine appeared to stand on a firmer basis. On 29 March 1885, Poundmaker—who as early as 1881 was labelled a troublemaker by the Department of Indian Affairs and who Reed recommended be removed as chief in 1883—travelled to Battleford to express loyalty to the Queen and have his band’s grievances addressed.[56] Upon his arrival, Poundmaker found Battleford evacuated, owing to pervasive paranoia among the residents over the intent of the First Nations—fostered by Laurie and the Department of Indian Affairs.[57] Consequently, when a number of settlers and Métis engaged in the looting of the abandoned town-site, Poundmaker and his band were implicated in the ‘siege’ by Dominion officials and the people of Battleford.[58] That Riel had sent an unrequited call to arms to take Battleford constituted proof of Poundmaker’s complicity.[59]

A more dubious piece of evidence was discovered by Colonel William Otter upon his relief of Battleford on 24 April.[60] A letter from Poundmaker to Riel was produced appearing to prove collusion. However, as Stonechild and Waiser demonstrated, the letter was crafted under duress by the farm instructor Robert Jefferson who was compelled by Oopinowaywin—a headman of Poundmaker’s—to add Poundmaker’s signature.[61] Citing the letter, Otter proposed an attack on Poundmaker’s camp at Cutknife Creek to General F.D. Middleton—who held supreme authority over military action during the North-West Resistance.[62] Middleton responded that such an attack would have been ill-advised.[63] Rather than comply with this order, however, Otter telegraphed Dewdney and received permission to attack.[64]

The result of Otter’s assault on Poundmaker’s band at Cutknife Creek on 2 May 1885 demonstrated the precariousness of the Dominion’s continuity in the North-West.[65] Failing to take Poundmaker’s band by surprise and frustrated by the tactics of the Plains Cree-Assiniboine warriors, Otter’s forces suffered substantial losses.[66] While Otter would later claim that losses were light in comparison to the purported 100 lost by Poundmaker, this account was employed to salvage the attack and Otter’s legacy. Rather, Otter’s force suffered eight deaths and 14 seriously wounded compared to five dead among the Plains Cree-Assiniboine.[67] It has been argued that had Poundmaker not interceded, the Plains Cree-Assiniboine warriors would have wiped out the entire battalion.[68]

The restraint and mercy exercised by Poundmaker at Cutknife Creek was rarely, if ever, reciprocated by Dominion forces. For example, an individual Cree warrior at the Battle of Frenchman’s Butte on 26 May 1885 was cut down by Dominion forces while surrendering under a white flag.[69] This instance preceded more institutionalized betrayals of good faith. After the Métis defeat at Batoche on 12 May 1885, and the ‘surrenders’ of Poundmaker and Big Bear on 26 May and 4 July 1885, the latter two leaders—along with One Arrow (a principal leader of the Woods Cree) who was forced at gunpoint to Batoche by followers of Riel—were put on trial for treason-felony.[70] Each leader received a sentence of three years in Stony Mountain Penitentiary—and, with the exception of Poundmaker, endured the humiliation of having their hair cut—effectively extinguishing First Nations recalcitrance in the North-West.[71]

To prevent the emergence of other leaders, the Dominion government sought to make an example out of eight perpetrators of the Frog Lake Massacre. Macdonald maintained publicly that the hangings of the eight perpetrators were an exercise of justice.[72] However, a similar fate did not befall Métis perpetrators of violence during 1885.[73] Of 26 Métis sentenced as a cohort by Judge Hugh Richardson, 11 were sentenced to seven years, three were sentenced to four years, four were sentenced to one year, and eight were acquitted.[74] The disparity between the treatment of First Nations and Métis perpetrators of violence is explained by private communications between Macdonald and Dewdney. Following requests by Dewdney to have the executions carried out as a public spectacle, Macdonald agreed, adding “the executions… ought to convince the Red Man that the White Man governs.”[75] In this pursuit, students from the Battleford Industrial School were made to watch in hopes, as Reed expressed, that the hangings would “cause them to meditate for many a day.”[76]

The Battleford Hangings—arguably the harshest instance of state-sponsored violence in Canadian history—were thus the final act of retribution for the apparent violence perpetrated against the Dominion by First Nations in the North-West.[77] The Resistance had not only imperilled the security the Dominion of the North-West but cost in the neighbourhood of $5 million to quash.[78] In his analysis of the Resistance, Macdonald stated in the House of Commons on 6 July 1885: “forgetting all that the Government, the white people and the Parliament of Canada had done for them, in trying to rescue them from barbarity… they rose against us.”[79] Macdonald thus portrayed the violence of 1885 as a military confrontation but admitted to Governor General Lansdowne that, “[w]e have certainly made it assume large proportions in the public eye. This has been done however for our own purposes, and I think wisely done.”[80]

In the House of Commons, Macdonald maintained that the purposes of Indian policy in the North-West were assimilatory. For example, in 1887, Macdonald argued that “the great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as possible.”[81] Macdonald’s public articulations of Indian policy belied the content of such policy, policy which took as its “great aim” the subjugation of the First Nations of the North-West and the maintenance of this subjugation—ambitions that Macdonald held well before the outbreak of violence in 1885.[82]

The development of post-1885 Indian policy did not occur in Ottawa. Instead, Reed compiled a series of recommendations which weaved its way through the chain of command to Macdonald.[83] The genesis of Indian policy in the North-West has prompted Richard Gwyn to assert that Macdonald resented the character of Indian policy after 1885.[84] However, the Prime Minister either marked his approval or modified the recommendations to suit his understanding of the North-West.[85] For example, Macdonald expanded the scope of Reed’s pass system to apply to all First Nations, regardless of loyalty during the North-West Resistance.[86] Although separation from the dominant society was imagined as a way to protect First Nations from the deprivations of settler society, the success which First Nations enjoyed as labourers without experiencing such deprivations would seem to render such protection obsolete.[87] Further, Indian policy in Central Canada had rejected separation as early as the 1850s when architects (among them Macdonald) found it counterproductive to the goal of assimilation.[88]

The NWMP also proved reticent to enforce the pass system.[89] It was well-known by Macdonald that the pass system constituted a blatant violation of the terms of the Numbered Treaties.[90] Knowing that inconsistent enforcement of the pass system could bring the authority of the Department of Indian Affairs into question—and therefore invite further challenges to this authority—Macdonald cautioned: “no punishment for breaking bounds can be inflicted & in case of resistance on the grounds of Treaty rights should not be insisted on.”[91] At the same time that First Nations were being prevented from accessing economic activity off-reserve, Reed sought to curtail economic activity on-reserve.

In Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (1990), Sarah Carter observed that agricultural activity on Indian reserves met with considerable success when competent farm instructors were supplied, and First Nations farmers were given adequate implements. For example, Louis O’Soup—who had earlier helped to de-escalate the Yellow Calf Incident—regularly produced yields comparable to settler farmers.[92] So successful were First Nations farmers that in 1888 Reed was regularly visited by settlers in Battleford complaining of unfair competition for markets.[93] To limit this competition Reed invoked two measures. First, in order to sell surplus agricultural yields (and any other produce on-reserve), permission had to be attained from the local Indian Agent.[94] Second, to limit the possibility of producing surplus yields, Reed invoked the language of Social Darwinism through the peasant farming policy. Reed reasoned that First Nations had to progress through the social evolutionary stages of agriculture to become properly assimilated, and thus, were relegated to the position of ‘peasant’ farmers.[95]

Macdonald employed a similar logic in launching an assault on the future labour power of First Nations. As early as 1883, Macdonald reasoned that the only way to ensure the success of assimilating First Nations children “would be to put them in central training industrial schools where they will acquire the habits and modes of thought of white men.”[96] The outwardly assimilationist conception of Residential Schools belies the nature of the instruction of, and the desired outcomes for, pupils. Although the prevailing historiography has identified the origins of Canadian Residential Schools in American Indian Industrial Schools, it has failed to investigate the origins of the latter institutions.[97] The Carlisle Industrial School, which Nicholas Flood Davin had visited while preparing his report advising the creation of Residential Schools in Canada, was modelled on institutions for the education of formerly enslaved Black Americans.[98] The Hampton Institute, for example, sought to provide freedmen with an education level suitable for a lower-class existence.[99] Dewdney’s preference for Industrial Schools, modelled on institutions for delinquent children, was thus part of an overall strategy to relegate the economic activities of Residential School graduates to a stature of inferiority.[100]

The effects of the pass system, permit system, peasant farming policy, and Residential School system compounded in frustration and destitution. That the Department of Indian Affairs lamented such frustration and destitution is not indicated by the historical record. Officials that attempted to offer relief were promptly dismissed. Charles Adams’ dismissal from the Prince Albert Agency in 1886 is demonstrative of the ill intent of the Department of Indian Affairs.[101] After the Inspector of Indian Agencies, T.P. Wadsworth had reported on irregularities “contrary to the rules of the Department” in Adams’ agency to Dewdney—which included the issuing of extra rations to a sick child and her mother—the Indian Commissioner reasoned that as a half-breed, Adams did not have the “firmness and tact” requisite of an Indian Agent.[102] F. Laurie Barron—the sole scholar to investigate Adams’ dismissal—accepted the reasoning of Dewdney as authentic.[103] However, the racial explanation does not accord with the fact that Adams was a patronage appointment as the brother-in-law of Macdonald’s Manitoba ally: Premier John Norquay—himself an English ‘mixed-blood.’[104]

Similar racial reasoning was employed in explaining the dismissal of Indian Agent Joseph Finlayson from the Touchwood Hills Agency in 1894.[105] In enforcing the peasant farming policy, Reed—who had ascended to the position of Indian Commissioner in 1888 when Dewdney joined Macdonald’s cabinet—barred the use of labour-saving machinery even when it could salvage a critical harvest.[106] Finlayson’s refusal to comply with this policy resulted in his dismissal.[107] In Reed’s recommendation for his dismissal, it was stated that as “one of the natives of the country” Finlayson was “imbued with Indian ideas.”[108] Curiously, scarcely more than a year before his dismissal, Finlayson was given only a “severe reprimand” following an investigation of intemperance—demonstrative of the fact that deviant social behaviour could be tolerated so long as it was not accompanied by the encouragement of progress among First Nations.[109]

When Macdonald’s Indian policy failed to facilitate the assimilation of First Nations, the onus was placed on the deficiencies of First Nations character. For example, Macdonald explained on 6 July 1885 in the House of Commons “that a savage was still a savage… until he ceased to be a savage.”[110] On 26 February 1886, Macdonald, in response to the Liberal M.C. Cameron’s indictment of the Department of Indian Affairs, explained that Indian policy was designed not to “render them still more idle and unwilling to do work than all Indians are.”[111] Scholars of Canadian Indian policy have accepted the authenticity of Macdonald’s claims. John L. Tobias reasoned that Macdonald’s Indian policy was consistent with the goals of Indian policy in Central Canada: namely, “protection, civilization, [and] assimilation.”[112] Similarly, in his analysis of Reed, Robert James Nestor argued that the pervasive racial thinking of the Victorian era shaped the formation of this policy.[113]

The deviation from stated policy and the truncation of First Nations economic progress—even over the objections of settlers—demonstrated the Department of Indian Affairs’ insincerity with regard to assimilation. For example, amidst the violence of 1885, the editor of the Prince Albert Times vehemently objected to the encouragement of hunting, fishing, and trapping as a supplement to rations since it was contrary to the goal of assimilation through agriculture.[114] In effect, the guiding principle of Indian policy in the North-West was to sow destitution and limit progress even at the cost of unnecessary expenses.

Still stronger evidence that Indian policy was not genuinely predicated on race and the goal of assimilation are the ethnic identity of many of its administrators and the inconsistency which characterized its application. Despite the reasoning of Dewdney and Reed with regard to the dismissals of Adams and Finlayson, English ‘mixed-bloods’ were regularly employed as farm instructors.[115] Further, amidst the demise of the bison herds in the late 1870s, the Dakota were left undisturbed and able to partake in productive economic activities.[116] Similarly, while Poundmaker, Big Bear, and One Arrow were sentenced to prison terms, Whitecap—the foremost leader of the Dakota in Canada—was acquitted despite the striking similarity between the circumstances of his arrest and those of the incarcerated leaders.[117] The minimal force with which Indian policy was applied to the Dakota may be explained only by the fact that these bands did not pose an immediate threat to the Dominion’s control of the North-West.[118]

Conclusion

In spite of overwhelming evidence, the prevailing historiography on Canadian Indian policy in the North-West has maintained the notion of its benevolent intent. For example, Gwyn cited the Electoral Franchise Act of 1885 as an “offer to Indians of enfranchisement, without any loss of their distinctive rights.”[119] While partially correct, this characterization neglects the fact that the legislation would have applied only to First Nations east of Lake Superior.[120] By Macdonald’s own admission, Canadian Indian policy in the North-West was informed principally by the balance of power in the region and his “fear [that] if Englishmen do not go there, Yankees will, and with that apprehension I would gladly see a Crown colony established there.”[121] The power which First Nations yielded in the region dissuaded Macdonald from pursuing an authentic policy of assimilation as in Central and Eastern Canada. Thus, while maintaining an assimilationist agenda in the public discourse, Macdonald acknowledged that “the whole thing is a question of management” until such time as the power of First Nations could be shattered.[122] Thus, the rhetoric of assimilation was employed to justify increasingly repressive measures in a social climate where notions of assimilation were more palatable to citizens literate in the tenets of Social Darwinism.[123] Erstwhile, officials in the Department of Indian Affairs under Macdonald’s direction employed Canadian Indian policy to foster (and ensure) destitution among First Nations to secure Dominion control of the North-West.

- John L. Tobias, “Protection, Civilization, Assimilation: An Outline History of Canada’s Indian Policy,” in The Prairie West: Historical Readings, 2nd ed., eds. R. Douglas Francis and Howard Palmer (Edmonton: Pica Pica Press, University of Alberta Press, 1995), 207. For the purposes of this paper, the North-West refers to the territories comprising Alberta, Saskatchewan, Manitoba, and parts of Northwestern Ontario. See J.R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada, 4th ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 170. ↵

- See Timothy C. Winegard, For King and Kanata: Canadian Indians and the First World War (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 2012), 22; D. Michael Jackson, The Crown and Canadian Federalism (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2013), 50; Richard Gwyn, “Rediscovering Macdonald,” in Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies, eds. Patrice Dutil and Roger Hall (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2014), 447; Raymond B. Blake, Jeffrey Keshen, Norman J. Knowles, and Barbara J. Messamore, Conflict & Compromise: Post-Confederation Canada (North York: University of Toronto Press, 2017), 32; Greg Piasetzki, “Sir John A. Macdonald Saved More Native Lives Than Any Other Prime Minister,” C2C Journal: Ideas That Lead, November 27, 2020, https://c2cjournal.ca/2020/11/sir-john-a-macdonald-saved-more-native-lives-than-any-other-prime-minister/. ↵

- J.R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens, 172. ↵

- Gerald Friesen, The Canadian Prairies: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987), 110-113. ↵

- Noel Evan Dyck, “The Administration of Federal Indian Aid in the North-West Territories, 1879-1885” (master’s thesis, University of Saskatchewan, 1970), 4. ↵

- A variety of efforts paralleled that of Yellow Quill’s band although tactics could vary. The Plains Cree obstructed the Geological Survey and threatened to violently prevent the construction of telegraph lines. Others, such as Henry Prince (the son of the renowned Peguis), used the Nor’wester (ironically the most vocal proponent of Dominion annexation of the North-West) to diplomatically assert their rights. See J.M.S. Careless, Brown of the Globe: Volume II: Statesman of Confederation, 1860-1880 (Toronto: The Macmillan Company of Canada Limited, 1963), 7; Laura Peers, The Ojibwa of Western Canada, 1780-1870 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1994), 46 and 203; Arthur J. Ray, Jim Miller, and Frank J. Tough, Bounty and Benevolence: A History of Saskatchewan Treaties (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2000), 103-104; J.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-Making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009), 153; Aimée Craft, Breathing Life into the Stone Fort Treaty: An Anishinabe Understanding of Treaty One (Saskatoon: Purich Publishing Limited, 2013), 43. ↵

- Ray, Miller, and Tough, Bounty and Benevolence, 98-99. ↵

- Garrett Wilson, Frontier Farewell: The 1870s and the End of the Old West (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina, 2007), 176. ↵

- Michael Asch, On Being Here to Stay: Treaties and Aboriginal Rights in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014), 155. ↵

- Ray, Miller, and Tough, Bounty and Benevolence, 99-101. ↵

- Canada, Report on the State of the Militia of the Dominion of Canada (Ottawa: I.B. Taylor, 1874), xi. ↵

- Jack F. Dunn, The North-West Mounted Police, 1873-1885 (self-pub., 2017), xiv and 5. ↵

- R.C. Macleod, “Canadianizing the West: The North-West Mounted Police as Agents of the National Policy, 1873-1905,” in The Prairie West: Historical Readings, 2nd ed., eds. R. Douglas Francis and Howard Palmer (Edmonton: Pica Pica Press, University of Alberta Press, 1995), 227. Significantly, Macdonald acknowledged in the House of Commons that the losses of life and public revenues sustained during the American Indian wars were substantial and regrettable. See Canada, House of Commons Debates: Third Session—Fifth Parliament, 6 July 1885 (John A. Macdonald) (Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co., 1885), 3119. ↵

- Dyck, “Federal Indian Aid,” 42. ↵

- The ramifications of this correction of the historical record are substantial. Since the Dominion attempted to settle the North-West without negotiating the extinguishment of Indian title pursuant to the Royal Proclamation, the impetus of the Numbered Treaties lies outside the parameters of the Royal Proclamation—bringing its applicability in the North-West into question. ↵

- Walter Hildebrandt, Views from Fort Battleford: Constructed Visions of an Anglo-Canadian West (Regina: Canadian Plains Research Centre, University of Regina, 1994), 15. ↵

- James Daschuk, Clearing the Plains: Disease, Politics of Starvation, and the Loss of Aboriginal Life (Regina: University of Regina Press, 2013), 108. ↵

- A.J. Looy, “Saskatchewan’s First Indian Agent, M.G. Dickieson,” Saskatchewan History 32, no. 3 (Autumn 1979): 104. ↵

- Looy, “M.G. Dickieson,” 112. ↵

- Ibid., 113. ↵

- Hugh Shewell, ‘Enough to Keep Them Alive’: Indian Welfare in Canada, 1873-1965 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004), 13. ↵

- Sarah Carter, Lost Harvests: Prairie Indian Reserve Farmers and Government Policy (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1990), 22. ↵

- John L. Tobias, “Canada’s Subjugation of the Plains Cree, 1879-1885,” in Sweet Promises: A Reader on Indian-White Relations in Canada, ed. J.R. Miller (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 212-239. ↵

- Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 215. ↵

- Ibid., 214-215. ↵

- Ibid., 216. ↵

- Ibid., 216-217. ↵

- Ibid., 216. ↵

- Ibid., 217. ↵

- Canada, House of Commons Debates: Fourth Session—Fourth Parliament, 27 April 1882 (John A. Macdonald) (Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co., 1882), 1186. ↵

- Donald B. Smith, “Macdonald’s Relationship with Aboriginal Peoples,” in Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies, eds. Patrice Dutil and Roger Hall (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2014), 75. ↵

- Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 140. ↵

- Such was the case in the agency of Indian Agent Robert J.N. Pither who, in 1880, withheld rations from First Nations leading to their spoliation having stayed in the storehouse for two years. In the same year, Indian Affairs was given its own department although it remained the responsibility of the Minister of the Interior. See Department of Indian Affairs. Annual Report for the Department of Indian Affairs for the Year Ended 31st December 1880 (Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co., 1881), 60; Brian Titley, The Indian Commissioners: Agents of the State and Indian Policy in Canada’s Prairie West, 1873-1932 (Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 2009), 7. ↵

- Isabel Andrews, “Indian Protest Against Starvation: The Yellow Calf Incident of 1884,” Saskatchewan History 28, no. 2 (Spring 1975): 41. ↵

- Ibid., 43. ↵

- Maureen K. Lux, Medicine That Walks: Disease, Medicine, and Canadian Plains Native People, 1880-1940 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 43. ↵

- Titley, The Indian Commissioners, 98. ↵

- Andrews, “Yellow Calf Incident,” 47; Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 37. ↵

- Andrews, “Yellow Calf Incident,” 47. Reed’s comments appear to have disproved the reasoning of Dewdney earlier in 1884 when he arranged for Crowfoot and other Blackfoot leaders to travel to Winnipeg on the railway. Dewdney intended that the visit would impress upon the leaders, “the supremacy of the white man and the utter impossibility of contending against his power.” See Dyck, “Federal Indian Aid,” 74. ↵

- Noel Dyck, “An Opportunity Lost: The Initiative of the Reserve Agricultural Programme in the Prairie West,” in 1885 and After: Native Society in Transition, eds. F. Laurie Barron and James B. Waldram (Regina: University of Regina, Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1986), 128; There appears to have been divergence in the opinion of policy architects over the futility of satiating First Nations. On the eve of the North-West Resistance, Reed and Dewdney requested more resources to attend to First Nations concerns. Macdonald replied that “no amount of concessions will prevent starving people from grumbling and agitating.” See Jean Bernice Drummond Larmour, “Edgar Dewdney, Commissioner of Indian Affairs and Lieutenant Governor of the North-West Territories, 1879-1888” (master’s thesis, University of Saskatchewan, Regina Campus, 1969), 171-172. ↵

- Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 225. ↵

- Larmour, “Edgar Dewdney,” 171; Beal and Macleod, Prairie Fire, 122; Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 225. ↵

- Larmour, “Edgar Dewdney,” 178. ↵

- Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 225. ↵

- Dempsey, Big Bear, 82; Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 225-226. ↵

- To some extent, this fear was misguided. Although warfare between the Plains Cree and Blackfoot Confederacy had ceased after the latter’s victory at Belly River in 1870, historic enmities prevented a productive alliance from forming. In fact, during the North-West Resistance, Macdonald had inquired about fielding a force of Blackfoot under Canadian command. See Hugh A. Dempsey, Red Crow: Warrior Chief (Saskatoon: Western Producer Prairie Books, 1980), 153; John S. Milloy, The Plains Cree: Trade, Diplomacy and War, 1790 to 1870 (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press, 1988), 117. ↵

- Dempsey, Big Bear, 82. ↵

- Dyck, “Federal Indian Aid,” 67. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 109. ↵

- Hildebrandt, Views from Fort Battleford, 72. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 116-117. ↵

- While referring to the violence at Frog Lake as a ‘massacre’ certainly aided Macdonald and the Dominion’s efforts to discredit First Nations, there is no indication that use of this term was consciously selected. On the contrary, little scholarship on the North-West Resistance departs from the term—which explains its use in this paper. See J.R. Miller, “The Northwest Rebellion of 1885,” in Sweet Promises: A Reader on Indian-White Relations in Canada, ed. J.R. Miller (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 251-252. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 115. ↵

- Dempsey, Big Bear, 159-160. ↵

- Miller, “The Northwest Rebellion of 1885,” 252. For an example of newspaper contributions to the hysteria of 1885, consider the Saskatchewan Herald’s argument that failing to take a hard stance against First Nations was “making them quite saucy and independent.” See Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 38. ↵

- Dyck, “Federal Indian Aid,” 64; Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 86. ↵

- Hildebrandt, Views from Fort Battleford, 67. ↵

- A. Blair Stonechild, “The Indian View of the 1885 Uprising,” in Sweet Promises: A Reader on Indian-White Relations in Canada, ed. J.R. Miller (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1991), 265. ↵

- George F.G. Stanley, The Birth of Western Canada: A History of the Riel Rebellions (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1963), 334-335. ↵

- Hildebrandt, Views from Fort Battleford, 75. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 139. ↵

- Hildebrandt, Views from Battleford, 77. ↵

- Beal and Macleod, Prairie Fire, 242. ↵

- It would appear that insubordination was pervasive under Middleton’s command. For example, during the Battle of Batoche, officers initiated the final assault against the orders of Middleton. See Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 163. ↵

- Carter, Lost Harvests, 126. ↵

- Beal and Macleod, Prairie Fire, 249. ↵

- See Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 143. ↵

- Stonechild, “The 1885 Uprising,” 269. ↵

- Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 201. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 72, 162, 166, 191. ↵

- The significance of hair in Plains First Nations cultures rendered this action a humiliation as it signified the subjugation of First Nations by the Dominion. Poundmaker was spared from this humiliation on the initiative of his adoptive father Crowfoot—the foremost Blackfoot chief and Dominion ally. Additionally, the imprisonment of First Nations leadership was undertaken not out of mercy but out of an understanding by Dewdney that First Nations resented imprisonment more than death. See Hugh A. Dempsey, Big Bear: The End of Freedom (Vancouver: Greystone Books, 1984), 184 and 192; Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 221; Shelley A.M. Gavigan, Hunger, Horses, and Government Men: Criminal Law on the Aboriginal Plains, 1870-1885 (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2012), 127; Bill Waiser, In Search of Almighty Voice: Resistance and Reconciliation (Markham: Fifth House Publishers, 2020), 19. ↵

- Smith, “Macdonald’s Relationship with Aboriginal Peoples,” 75. ↵

- Gwyn, Nation Maker, 476. ↵

- Prior to the North-West Resistance, Macdonald had encouraged administrators of justice in the North-West to co-operate with Dewdney’s goal of subjugation by rendering verdicts conducive to this goal. Judge C.B. Rouleau, who presided over the trial of the eight men hanged at Battleford, required no such cajoling. While initially sympathetic to First Nations grievances, the destruction of his property during the Resistance encouraged retribution from Judge Rouleau. See Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 227; Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 210. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 221. ↵

- Daschuk, Clearing the Plains, 156-157. ↵

- Larger numbers had been executed at once (for example, 12 men were hanged in the aftermath of the Lower Canadian Rebellion of 1873). However, the fact that public executions were no longer in practice by 1870 and that children were made to watch renders the Battleford Hangings still harsher. See Canada, An Act respecting procedure in Criminal Cases, and other matters relating to the Criminal Law, 1869, Vict. 33-34, p. 285, s. 109; F. Murray Greenwood, “The General Court Martial at Montreal, 1838-39: Operation and the Irish Comparison,” in Canadian State Trials, Volume II: Rebellion and Invasion in the Canadas, 1837-1839, eds. F. Murray Greenwood and Barry Wright (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2002), 299. ↵

- Larmour, “Edgar Dewdney,” 186. ↵

- Canada, House of Commons Debates: Third Session—Fifth Parliament, 6 July 1885 (John A. Macdonald), 3119. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 221. ↵

- J.R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Native-Newcomer Relations in Canada, 4th ed. (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018), 207. ↵

- Shewell, ‘Enough to Keep Them Alive’, 13. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 221. ↵

- Gwyn, Nation Maker, 488. ↵

- Lawrence Vankoughnet, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs to John A. Macdonald, 17 August 1885, Library and Archives (LAC), RG 10, Vol. 3710, File 19,550-3. ↵

- F. Laurie Barron, “The Indian Pass System in the Canadian West, 1882-1935,” Prairie Forum 13, no. 1 (Spring 1988): 28. ↵

- Barron, “Indian Pass System,” 31. ↵

- Tobias, “Protection, Civilization, Assimilation,” 209-210. ↵

- Carter, Lost Harvests, 153-154. ↵

- Barron, “Indian Pass System,” 28. ↵

- Vankoughnet to Macdonald, 17 August 1885, LAC, RG 10, Vol. 3710, File 19,550-3. ↵

- Despite substantial success, reserve agriculture was also mired by insufficient funding and the patronage appointments that populated the Department of the Interior/Department of Indian Affairs—many of whom were ill-equipped in a region largely devoid of agriculture prior to the 1870s. See Andrews, “Yellow Calf Incident,” 46; Carter, Lost Harvests, 85-86 and 113. ↵

- Sarah Carter, “Two Acres and a Cow: ‘Peasant’ Farming for the Indians of the Northwest, 1889-97,” Canadian Historical Review 70, no. 1 (1989): 36. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/573338. ↵

- Carter, Lost Harvests, 156. ↵

- Ibid., 212-213. ↵

- Canada, House of Commons Debates: First Session—Fifth Parliament, 9 May 1883 (John A. Macdonald) (Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co., 1883), 1108. ↵

- J.R. Miller, Shingwauk’s Vision: A History of Native Residential Schools (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1996), 101. ↵

- E. Brian Titley, A Narrow Vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the Administration of Indian Affairs in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1986), 76. ↵

- K. Tsianina Lomawaima, They Called It Prairie Light: The Story of Chilocco Indian School (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 4. ↵

- Titley, The Indian Commissioners, 74. ↵

- Waiser, Almighty Voice, 37. ↵

- T.P. Wadsworth to Edgar Dewdney, 16 November 1886, LAC, RG 10, Vol. 3773, File 35764. ↵

- F. Laurie Barron, “Indian Agents and the North-West Rebellion,” in 1885 and After: Native Society in Transition, eds. F. Laurie Barron and James B. Waldram (Regina: University of Regina, Canadian Plains Research Centre, 1986), 142. ↵

- L.W. Herchmer, Inspector of Indian Agencies to Dewdney, 14 February 1886, LAC, RG 10, Vol. 3736, File 27218; W.L. Morton, Manitoba: A History (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1967), 196-197; W.G. Hardy, From Sea Unto Sea: The Road to Nationhood, 1850-1910 (Garden City: Doubleday Canada Limited, 1960), 399. ↵

- Hayter Reed, Memorandum for the Information of the Superintendent General, Relative to Mr. Agent Finlayson, of Touchwood Hills Agency, 26 July 1894, LAC, RG 10, Deputy Superintendent General (DSG) Letterbooks, Vol. 15, p. 382. ↵

- Carter, Lost Harvests, 222. ↵

- Ibid., 223. ↵

- Reed, Mr. Agent Finlayson, LAC, RG 10, DSG Letterbooks, Vol. 15, p. 382. ↵

- Reed, Memorandum, 24 February 1893, LAC, RG 10, Vol. 3900, File 99,079. ↵

- Canada, House of Commons Debates: Third Session—Fifth Parliament, 6 July 1885 (John A. Macdonald), 3119. ↵

- Canada, House of Commons Debates: Fourth Session—Fifth Parliament, 26 February 1886 (John A. Macdonald) (Ottawa: Maclean, Roger & Co., 1885), 22. Emphasis added. ↵

- Tobias, “Protection, Civilization, Assimilation,” 207. ↵

- Nestor, “Hayter Reed,” 28. ↵

- A.J. Looy, “The Indian agent and his role in the administration of the North-west superintendency, 1876-1893” (doctoral thesis, Queen’s University, 1977), 232-233. ↵

- Tobias, “The Plains Cree,” 226. Additionally, Thomas Quinn (whose commitment to rations policy cost him his life) was of partly Sioux ancestry. See Dempsey, Big Bear, 116. ↵

- Peter Douglas Elias, The Dakota of the Canadian North-West: Lessons of Survival (Regina: University of Regina Press, Canadian Plains Research Centre, 2002), 56-57. ↵

- Stonechild and Waiser, Loyal till Death, 148-149 and 210. ↵

- J.W. Daschuk, Paul Hackett, Scott MacNeil, “Treaties and Tuberculosis: First Nations People in late 19th-Century Western Canada, a Political and Economic Transformation,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History 23, no. 2 (Fall 2006): 322. https://doi.org/10.3138/cbmh.23.2.307. ↵

- Gwyn, “Rediscovering Macdonald,” 446. ↵

- Tobias, “Protection, Civilization, Assimilation,” 217 ↵

- J.R. Miller, “Macdonald as Minister of Indian Affairs: The Shaping of Canadian Indian Policy,” in Macdonald at 200: New Reflections and Legacies, eds. Patrice Dutil and Roger Hall (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2014), 319. ↵

- Ged Martin, John A. Macdonald: Canada’s First Prime Minister (Toronto: Dundurn Press, 2013), 167. ↵

- Titley, The Indian Commissioners, 206. ↵