10 How the West was Lost: Pierre E. Trudeau’s 1980-1985 National Energy Program and Western Alienation

Jesse Fuchs

Introduction

It is the summer of 1973 in North America. Marvin Gaye and Jim Croce are topping the music charts, the United States has ended its war in Vietnam, pride events are taking place in cities across Canada for the first time in history,[1] the President of the United States was insisting he is not a crook,[2] and the international price of oil is a cool $3.40 a barrel.[3] Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, in the Middle East, a conflict is mounting between Israel and an Arab coalition led by Egypt and Syria. The conflict escalates to war when the Arab Coalition attacks Israel on the Jewish holy day, Yom Kippur. Global oil prices spike three-fold. Hostilities would eventually end between Israel, Egypt, and Syria, and global oil prices remained steady until 1979, when a revolution in Iran caused global oil prices to climb once again.

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the Western provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, Canada’s major producers of oil, exported most of their oil east to either Ontario and Quebec or south to the United States at world prices.[4] The world price of oil is the calculated by taking the average of the West Texas Intermediate market, the Fateh Petroleum Market, and The Dated Brent Petroleum Market.[5] That all changed in the 1970s, when the Organization of the Petroleum Export Countries (OPEC) oil embargo and the Iranian Revolution of 1979, saw oil prices soar from around three dollars in the early 1970s to over $34 in 1980.[6] The oil-rich provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan began to enjoy healthy profits as the US increased the volume of oil imported from Canada. The two provinces that had once struggled economically, looked to capitalize further on oil revenue by creating financial safe guards. In 1975, Saskatchewan NDP Premier Allan Blakeney created SASKOIL, a crown corporation to capture a greater share of oil production revenues for the province.[7] In 1976, Alberta was flush with cash and created a Heritage fund, where 30 percent of oil revenue would be deposited for future generations. [8] [9] Not all of Canada was enjoying the financial windfall of high oil prices. While the Western provinces were generating increased tax revenues from exporting excess oil reserves, Eastern Canada, which was dependent on oil imports, suffered under the financial strains of high gasoline prices. The situation became a crisis in Canadian federalism.

On 18 February 1980, the Liberal Party won the federal election with Pierre E. Trudeau at the helm. The Liberals won a majority government with 147 seats but lacked representation west of Manitoba, where Conservatives dominated the vote. Although Trudeau had resigned as Liberal leader after losing the 1979 election to the Progressive Conservatives and Joe Clark, he returned in 1980 with an ambitious political agenda. For the next four years, his goals consisted of quashing the French separatist movement, patriating the constitution, creating a charter of rights and freedoms, developing a national identity based on bilingualism and multiculturalism, and navigating a decade-long global energy crisis that had inflated the cost of importing oil and created an economic crisis in Eastern Canada. One of his most challenging issues on his agenda was to deal with the national energy crisis. Without western representation in his cabinet,[10] Prime Minister Trudeau and his Minister of Energy, Marc Lalonde, created a plan to make Canada self-sufficient in oil by increasing national ownership of oil and gas companies, to set the price of oil from Alberta and Saskatchewan to half the rate of international prices for domestic imports, to impose new taxes on oil exported from the Western provinces to the United States, and to use federal revenue to subsidize prices in Eastern Canada.[11] Such policies became the foundation of the National Energy Program (NEP) that was revealed eight months later, in October 1980.[12] The NEP reignited feelings of western resentment towards the Prime Minister and the federal government, while creating a national unity crisis that threatened the Canadian nation.

Not so Quiet on the Western Front: History of Western Resentment Towards Ottawa

Western resentment towards the central provinces of Canada and the federal government was not a recent phenomenon. It can be traced to the mid-1800s shortly after Confederation. In the late 19th century, the Canadian government was concerned with securing land for resources and keeping the Americans out of the northwest. Canadian westward expansion was achieved in 1870, when Ottawa purchased Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company, annexing it to Canada. The First Nations, Metis people, and the colonial trappers living on Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territory were not consulted on either the purchase or the transfer of ownership of the large swaths of land to the Dominion. The North-West Rebellion of 1885, led predominantly by Metis in the region, was fueled by the discontent and distrust of the central Canadian government.[13] Colonization ensued when the uprising was defeated during the Battle of Batoche, and the west became, in many ways, an economic colony of central Canada.[14] The Western feeling of being considered a colony was accentuated by John A. Macdonald’s National Policy in 1879, which Saskatchewan Premier Allan Blakeney described in 1980 as “an act of political will which pushed Canadian settlement west beyond the shield” but led to the region being controlled and exploited by resource and railways interests of Central Canada.[15]

Western alienation is the term used to describe the feelings of western resentment towards Ottawa. Western alienation is unique since provincial and municipal governments in Manitoba, Alberta, and Saskatchewan do not face the same level of resentment from their citizens as the federal government does.[16] Author Helen Mackenzie describes Western alienation as the “… sense of estrangement from central Canada economically, politically, and, to an extent, culturally.[17]” This feeling of estrangement is pervasive in Western Canada as it transcends age, education, class, or occupation. It has led to a distinctive culture and government policy from governments in Western Canada that have been based on a sense of political isolation from, and the exploitation by, the more populous regions in the Canadian federal political system.[17]

Pierre E. Trudeau had few supporters west of Ontario, especially after the late 1970s. Although generally more conservative in their beliefs than the eastern provinces, Alberta and Saskatchewan’s issues with Trudeau’s government were not merely cultural and ideological. Liberal policies, such as access to abortion, homosexuality, bilingualism and even the metric system, pushed some western voters away but the greatest resentments and dissatisfactions were over fiscal and economic matters, and particularly over resource-development policies.[18] It is common for people living west of the Canadian Shield to believe that their economic development has been impeded by national tariffs, freight rates, transportation policies, federal disallowance, agriculture policies, and national energy management, all imposed by what, at times, seemed to be an insensitive federal government.[19] Moreover, Trudeau was not afraid to challenge the Western provinces and doing so further strained relationships with the region. Within Saskatchewan, his last bridge may have been burned when he asked “Well, why should I sell the Canadian farmers’ wheat?[20]” at a Winnipeg Liberal gathering in 1968.

During the 1970s and the 1980s, western frustration with the federal government was, however, mainly centered round the federal government’s colonial attitude regarding natural resources, which had become a significant source of revenue for western provinces, as well as the belief that the federal government was attempting to restrain economic growth there. Before the 1973 oil crisis, Ottawa had little interest in helping the struggling western provinces by, for example, applying taxes to the Eastern province’s main exports of timber, nickel, gold, or hydroelectric power and use that tax revenues to supplement the Western economies. Ontario and Quebec began exporting hydroelectric power to the United States at the turn of the last century. In the west, electricity prices were five times that of Ontario, but federal energy policy was not adjusted – or energy exports to the US taxed aggressively — to reduce higher power rates in Saskatchewan and Alberta.[21] It was not until Western provincial revenue grew sharply in the 1970s from oil extraction that the federal government adjusted national policies to target provincial earnings on resource exports. And then, the revised policy only applied to western oil exports[22] and not the offshore resources under federal jurisdiction being developed in the Atlantic region.[23] The anger and resentment brewing in Western Canada was captured in an article by Mark Lisac in the Edmonton Journal. He identified the inconsistency of Trudeau’s policy choices and their impact on the western provinces, when he wrote, “He [Trudeau] saw no need to sell farmers’ wheat. He did see a need to intervene in energy pricing, foreign investment and wage and price levels. Each choice, interventionism or not, seemed to go against western interests.[24]”

From Have not to Have – Global Oil Shocks and Western Canadian Oil Revenue

Prior to 1973, despite growing US demands for oil , Canadian federal energy policy focused on ensuring Canadian reserves could meet domestic requirements.[25] Ottawa began limiting oil exports and applied a tax of $0.40 a barrel to oil headed south to the US.[26] Ian Muller describes the changes as focusing “… on the need for Canada to protect Canadian reserves from international oil shortages as well as insulating the domestic price from a volatile world market.[27]” For domestic trade, the price of oil was capped at $3.80 a barrel. [28] An imaginary line was drawn at the Ottawa Valley that would dictate what part of the country was supplied by international imports and what side was supplied by Alberta. Areas west of the line was supplied by Alberta crude, and the portions of the country east of it was primarily supplied by Middle Eastern oil brought in through the United States.[29]

In October 1973, the situation changed. The United States provided Israel with substantial military aid after Syria and Egypt attacked Israel on 6 October 1973. The following day, Saudi Arabia and the Arab members of OPEC reduced international oil exports and placed an embargo on oil shipments to Israel’s supporters. Global oil prices rose from $2.90 to $11.65 a barrel,[30] and oil-exporting nations had to rely on conserving domestic reserves instead of exporting to embargoed nations.[31] The cost of importing oil rose drastically for the United States and Canada, and the price of gasoline at the pumps followed suit. Higher oil prices were good news for Canada’s oil-rich provinces that exported substantial quantities of crude to their neighbours to the south. With oil prices skyrocketing, profits were at an all-time high. Canada’s smaller population meant less demand for oil, creating less dependency on imported energy, and the detrimental effects of the embargo in Canada paled in comparison to that of the United States.

When the Levy Breaks: The National Energy Program

In 1980, as Pierre E. Trudeau’s Throne Speech addressed energy and resource policy, he emphasized the importance of Canadian ownership of oil and using Canada’s own reserves to benefit the entire country.[32] In October, 1980, the Trudeau government unveiled a new approach to energy policy in the National Energy Program (NEP). The NEP had three main objectives:[33] provide security of energy supply for Canadians, offer Canadians the opportunity to participate in the petroleum industry, and establish oil pricing and revenue sharing that was fair to all Canadians. The 120-page document accompanying the new policy outlined the problems, program, and the impacts. The NEP looked to achieve its main objectives by creating federal incentives for developing new oil projects, offering programs for promoting energy conservation and alternative energy sources, requiring a 50 percent Canadian ownership in companies involved in new production, and engaging global partners on renegotiating international trade agreements. [34][35]

Ottawa’s share of energy revenue grew with new revenue-sharing strategies that restricted the amount and frequency of price increases, and with new taxes and incentives, including the Petroleum and Gas Revenue Tax (PGRT), the Natural Gas and Gas Liquids Tax (NGGLT), and the new Petroleum Incentive Program (PIP) which encouraged oil development by Canadian companies.[36] Perhaps the most controversial objective of the NEP was the blended pricing system. The blended pricing system restricted the cost of domestic oil imports to 75 percent of global prices. Blended pricing kept Western Canadian oil shipped to Central Canada below the world price to redistribute and equalize the burdens and benefits of pricing across the entire country.[37] The federal government’s policies clearly represented a more interventionist stance towards an increasingly profitable oil industry.[38]

The provincial response to the NEP varied, but the Western provinces that had been benefiting financially from oil exports offered the most critical response.[39] In a province-wide address in reaction to the NEP, Alberta Premier Peter Lougheed called the Federal budget and the NEP “stupid” and “the worst economic and financial decision in (Canadian) history.” He blamed a “select group” within Ottawa for not allowing Alberta to be even “moderately independent” and used the word “storm” to describe the inevitable forthcoming political climate being created as Western provinces responded to the restrictive NEP.[40] Although lacking the strong language that Lougheed used, Saskatchewan’s NDP Premier Allen Blakeney’s response was just as critical. In a speech at Toronto’s Osgoode Hall Law School, Blakeney described the history of the relationship between Western Canada and the federal government, outlining past and present policies that he claimed restricted economic growth within the west while favouring the central provinces’ economic and social agendas.[41]

It was all the more disturbing to Lougheed and Blakeney as Section 109 of the British North America (BNA) Act concedes ownership and control of natural resources to the provinces.[42] In response to the NEP, they often cited the BNA Act and argued that the PGRT, for instance, was a well-head tax that infringed on provincial rights.[43] Alberta called the NEP a “Canadianization” policy that bolstered federal power within the Canadian energy industry while destroying Alberta’s economy.[44] The Alberta government retaliated to the NEP by reducing oil shipments to Eastern Canada, challenging the constitutionality of the PGRT and NGGLT taxes in court, and withholding approval of new mega projects in the northern Alberta oil sands.[45]

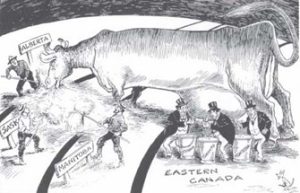

Western Canadian resentment of Eastern Canada and the federal government grew substantially after the NEP was fully implemented. At the heart of the NEP, the Western premiers believed, was money and power.[46] In 1980, prior to the NEP, federal oil and gas revenue share was 13.1 percent of the total national revenue. After the NEP was put in place in 1982, the federal government’s share of oil and gas revenues more than doubled to 27.4 percent. At the same time, the provincial government’s share of oil and gas revenues dropped from 45.7 to 32.3.[47] From 1980 to 1984, the price of Canadian oil was held at half the global price while the federal government used its new share of profits from the oil industry in Alberta and Saskatchewan to subsidize oil imported for the rest of the country. Lost revenue for Alberta alone was estimated to be as high as $60 billion.[48] The NEP was blamed for multinational energy companies deciding to leave Canada, further reducing investment for oil producing provinces and resulting in the loss of thousands of jobs in Western Canada.[49] Western newspaper columnist Norm Ovenden describes the 1980 Liberal budget that introduced the NEP as “… one of the most disastrous budgets in Canadian history; a fiscal blueprint which deepened the western suspicion of all things Liberal, plundered the Alberta treasury.”[52] Ovenden captured the sentiments of an entire province when he wrote, “Alberta was treated as a colony which could not be allowed to keep the windfall profits of soaring petroleum prices at the expense of Canada’s manufacturing heartland.”[50]

All for One and One for All: Trudeau’s Response to Western Disdain

Pierre Elliott Trudeau’s legacy is a polarized one. On the positive side, Trudeau advocated for human rights and equality. He was intelligent, charismatic, and a dynamic politician that inspired many. His speeches were calculated and direct, often powerful enough to impress even the most fractious opponents.[51] He is credited with quelling the Quebec sovereignty movements in the 1960s and 1970s in the name of national unity by introducing such policies as bilingualism with the Official Languages Act in 1969. He cemented fundamental freedoms as well as the democratic, mobility, legal, equality, and language rights of Canadian citizens by including the Charter of Rights and Freedoms in the patriated Constitution Act of 1982.[52] On the negative side, many regarded Trudeau as stubborn and arrogant, not afraid of inciting national controversy for his beliefs and for his staunch support of Canadian federalism. He saw Canada as a nation, a collective greater than the sum of its parts, and rejected special status for any province. [53]

Trudeau’s quest to assert the federal government’s power following the decentralization of the 1960s and 1970s has been described by author Bruce Pollard as a “new federalism”.[54] It consisted of replacing provincial consultation with unilateral decision-making. Pollard contends, “One area which exemplified the “new federalism” approach was energy policy.”[55] In 1969, during a television interview with the CBC, Trudeau affirmed his approach to unity and nationalism. When asked if “…the prime minister understand[s] the western point of view?” by the CBC interviewer, Trudeau responded by acknowledging that the immense geographical size of Canada can create regional loyalties where provinces feel disconnected from national issues. He said it was the federal government’s responsibility to make hard decisions: “It’s normal that a government, a central government in a large country like this, will have to make decisions which will sometimes favour one part of the country and sometimes favour another…” In that interview, Trudeau foreshadows the NEP by mentioning oil specifically, saying “…whether it be with tariffs or with oil… we are always making some allocation of resources which means we are taxing one part of the country to help another or putting tariffs on one part of the country to help another…” Trudeau’s frustration with a province-first rhetoric was clear, and he acknowledged that, in his opinion, too often in Canada people forget that they are a part of a nation, and that Canadians should “… pull up our sleeves and not just gripe and bitch [but] get in there and make sure we are taking the decisions” that benefit the whole national community. [56]

In his memoirs, Trudeau acknowledges the role of government to create a fair and equitable society for all citizens or, in his own words, to “take from the rich and give to the poor.” During the international oil crises of the 1970s and early 1980s, he believed he was managing the crisis by doing precisely that – redistributing wealth from one region of Canada to another. He viewed Western provinces as rich, and feared they were taking advantage of the high energy prices without regard for the hardship it created in the central provinces of Quebec and Ontario. In the West, many voters believed that Trudeau was making a political decision to appeal to the larger populations that had ensured the Trudeau-led Liberals of their majority government in 1980.[57] In a sense, it might be argued that Canada as a whole was mainly unaffected during the international oil crises, but they paved the way for a domestic crisis that was, ultimately, the result of the federal government’s actions and Trudeau’s approach to the crisis. By attempting to mitigate the price increases for Canadians dependant on imported oil at the expense of the energy-producing provinces, Trudeau created serious divisions in the country. The domestic crisis resulted from the 1980 National Energy Program and the interprovincial turmoil that followed its creation.

There are many ways a prime minister can navigate a crisis. Pierre E. Trudeau chose to maintain the status quo in oil pricing that Canada had adopted years earlier. He believed he was championing national unity through his new nationalist policy. Those views had been evident during a speech during the first session of the thirty-second Parliament on 15 April 1980. It was a powerful speech, one that reaffirmed the sentiments he expressed during the 1969 CBC interview on western alienation eleven years prior. Trudeau disregarded regional loyalties and promoted national pride, saying, “Very often we hear Quebeckers or Albertans say “I am a Quebecker” or “I am an Albertan,” but if you really press them and examine them, they will always say “I am a Canadian first and a Quebecker second” or “an Albertan second.” What he advocated was a national duty and asked “… that disagreement not be based on regional interests, on the fact that it might be the duty of provincial governments to serve but be based on the concept of the whole which we try to serve in our different ways.” In true Trudeau fashion, he did not deviate from his core idealism of a unified Canadian national interest and a strong federal presence. He went on to state, “… the concept of sharing can only be guaranteed, I repeat, if there is a national government which is prepared to state that the national interest must prevail in any situation of conflict over regional differences.”[58]

Trudeau’s determined stance towards naysayers and his usually impenetrable exterior would eventually soften on energy policy, perhaps in the interests of maintaining national unity during the energy crisis. Although Trudeau and the federal government dismissed Western disdain and threats of separatism, the infamous “Let the Eastern bastards freeze in the dark” bumper stickers that began circulating in the early 1980s struck a chord with the Prime Minister. He would regret the negative response to the NEP in the West and worried that “kind of negative attitude could hurt national unity.”[59] Within a year of the NEP, changes were made to soften the economic impact on Western provinces. Understanding the importance of national unity, Lougheed and Trudeau agreed on a pricing and revenue sharing in 1981. The change would ease regional tensions that the NEP had created but maintained most of the intentions of the original NEP. Bruce Pollard writes, “The agreement [was] formed out of necessity.”[60]

Conclusion

The Yom Kippur War Oil Crisis of 1973 and the Iranian Revolution Oil Crisis of 1979 fueled regional resentment and conflict in Canada between the Western provinces and the federal government. During the 1970s in the midst of the international oil crises, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau considered Alberta and Saskatchewan’s revenue from international oil exports as a benefit for all Canadians and believed that it should be used to mitigate the high cost of importing oil in the eastern provinces and ease the financial burden. Trudeau fancied himself a modern-day Robin Hood, who believed that the nation’s wealth had to be shared by all Canadians, and in 1981, created the National Energy Program to provide security of energy supply for Canadians, offer Canadians the opportunity to participate in the petroleum industry, and establish an oil pricing and revenue sharing arrangement that he considered fair to all Canadians.[61] The NEP effectively transferred greater control of natural resources in the provinces to the federal government, and infuriated Western Canada, where the policy was regarded as an attack on their economy. [62] It was described in Alberta and Saskatchewan as the “single worst economic decision of Canada’s 20th century.”[63] The West rejected Trudeau’s insistence that oil was Canada’s resource, regardless of where it was produced and that oil revenue should benefit all Canadians. The creation of the NEP cost Trudeau’s Liberal party dearly in the 1984 election, when the Progressive Conservative party won the greatest number of seats ever in any federal election, including every seat in Alberta and Saskatchewan.[64] In fact, the memories of Pierre Trudeau and his controversial energy policy remain vivid even today, as demonstrated with a recent conversation with an Albertan oil industry worker: “I will never forget… I’d never support the federal or provincial Liberals because of that. [That bill essentially] stole about $60 billion from Alberta to benefit Ontario and Quebec.”[65] Politicians, too, still use the NEP in their campaigns. Former Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper, whose roots are in Alberta, described the NEP as a product of not only a regional misunderstanding, but also the poor response to a crisis by a greedy federal government whose “ideological motivations directly or indirectly [were] hostile to Alberta and its society.” [66] That is the way Trudeau’s response to the energy crisis is remembered in Western Canada. Without a doubt, his approach to the energy crisis renewed a sense of alienation in the West and, in the process, threatened to tear apart the Canadian national fabric.

- For the first time, national gay rights events are taking place in major Canadian cities across the country. https://www.queerevents.ca/canada/pride/history ↵

- In the summer of 1973, President Richard Nixon was in the midst of the Watergate scandal and refusing to turn over presidential tape recordings. It was not until November when he famously states, “I am not a crook.” https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/nixon-insists-that-he-is-not-a-crook ↵

- Government of Canada, The National Energy Program, 1980, 24. ↵

- Ian Muller, "Evolving Priorities: Canadian Oil Policy and the United States in the Years Leading Up to the Oil Crisis of 1973." Order No. MR43753, University of Waterloo, Ontario. 2008,18. ↵

- https://www.ibisworld.com/us/bed/world-price-of-crude-oil/990007/ ↵

- https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2019/03/05/what-irans-1979-revolution-meant-for-us-and-global-oil-markets/ ↵

- https://web.archive.org/web/20100130044541/http://esask.uregina.ca/entry/blakeney_allan_e_1925-.html ↵

- https://www.alberta.ca/heritage-savings-trust-fund.aspx ↵

- https://greatcanadianspeeches.ca/2019/11/28/peter-lougheed-albertas-oil-october-1980/ ↵

- Bruce G Pollard, “Canadian Energy Policy in 1985: Toward a Renewed Federalism?” Publius: The Journal of Federalism, Volume 16, Issue 3, Summer 1986,165. ↵

- Ibid.,165. ↵

- Nor. Ovenden, “Now THIS Was a Tax Revolt; When Pierre Trudeau Decided to Redistribute the Country’s Oil Wealth, Alberta Really Got Mad: FINAL Edition.” Edmonton Journal. Edmonton, Alberta. 1995, 2. ↵

- Daryl Boychuk, Western Alienation: A Study Done at the Political Science Department, Regina, Saskatchewan. University of Regina 1982, 9-10. ↵

- Allan Blakeney, “Notes for Remarks by Premier Allen Blakeney of Saskatchewan – Western Alienation – Friday, April 11, 1980.” Osgood Hall, Ontario. 1980. P.10. ↵

- Ibid, 9. ↵

- Shawn Henry, “Revisiting western alienation: towards a better understanding of politicalalienation and political behaviour in western Canada,” (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Alberta. 2000. P.7. ↵

- On this point see, Henry, “Revisiting western alienation.” ↵

- Mark Lisac, “Trudeau’s Western Legacy: You Must Look Past the NEP to Appreciate What the Former PM Meant to the Western Provinces,” Edmonton Journal, 2000, 2. ↵

- Helen McKenzie, Western Alienation in Canada. Rev. ed., 1984, 2-8. ↵

- Mark Lisac, “Trudeau’s Western Legacy: You Must Look Past the NEP to Appreciate What the Former PM Meant to the Western Provinces.” ↵

- Blakeney, “Notes for Remarks by Premier Allen Blakeney of Saskatchewan – Western Alienation – Friday, 15. ↵

- Ibid., 14-15. ↵

- Bruce G. Pollard, “Canadian Energy Policy in 1985: Toward a Renewed Federalism?” Publius: The Journal of Federalism, Volume 16, Issue 3, Summer 1986, 165. ↵

- Lisac, “Trudeau’s Western Legacy: You Must Look Past the NEP to Appreciate What the Former PM Meant to the Western Provinces,” 2. ↵

- Ian Muller, "Evolving Priorities: Canadian Oil Policy and the United States in the Years Leading Up to the Oil Crisis of 1973." Order No. MR43753, University of Waterloo, Ontario. 2008, 87. ↵

- Ibid., 88. ↵

- Ibid., 88. ↵

- Ibid., 89. ↵

- Ibid., 110. ↵

- https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/oil-shock-of-1978-79 ↵

- Muller, "Evolving Priorities: Canadian Oil Policy and the United States in the Years Leading Up to the Oil Crisis of 1973," 10. ↵

- Alexander Washkowsky, Braden Sapara, Brady Dean, Sarah Hoag, Rebecca Morris-Hurl, Dayle Steffen, Joshua Switzer, and Deklen Wolbaum, Canada and Speeches from the Throne: Narrating a Nation, 1935-2015. University of Regina, Regina, Saskatchewan. 2020, 37. ↵

- Pollard, “Canadian Energy Policy in 1985: Toward a Renewed Federalism?,” 165. ↵

- Ibid., 165. ↵

- Washkowsky, Canada and Speeches from the Throne: Narrating a Nation, 1935-2015, 37. ↵

- Pollard, “Canadian Energy Policy in 1985: Toward a Renewed Federalism?,” 164. ↵

- Ibid., 164. ↵

- Barbara Jenkins, “Re-examining the ‘obsolescing Bargain’: A Study of Canada’s National Energy Program.” International organization 40, no. 1, 1986, 145. ↵

- Ibid., 167. ↵

- “The Word Is ‘Storm’: Nov. 20, 1980: The NEP: National Edition.” National Post (Toronto). Don Mills, Ontario. 2000, 1. ↵

- Blakeney, “Notes for Remarks by Premier Allen Blakeney of Saskatchewan – Western Alienation”. ↵

- Mary Joy Aitken, “The National Energy Program: A Case Study of State Energy Policy,” Master’s thesis, University of Alberta, Alberta. 1983, 71. ↵

- Pollard, “Canadian Energy Policy in 1985: Toward a Renewed Federalism?” 167. ↵

- Ibid., 167 ↵

- Ibid., 167 ↵

- Ovenden, “Now THIS Was a Tax Revolt; When Pierre Trudeau Decided to Redistribute the Country’s Oil Wealth, Alberta Really Got Mad: FINAL Edition,” 3. ↵

- Jenkins, “Re-examining the ‘obsolescing Bargain’: A Study of Canada’s National Energy Program,” 151. ↵

- Ibid., 3. ↵

- Ibid., 3. ↵

- Ibid., 1. ↵

- Lisac, “Trudeau’s Western Legacy: You Must Look Past the NEP to Appreciate What the Former PM Meant to the Western Provinces: Final Edition,” 1. ↵

- Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, s 15, Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act 1982 (UK), 1982, c 11, (QL). ↵

- Robert L. Wereley, “NEP Didn’t Cause Alberta’s Woes: Final Edition,” Edmonton Journal. 2000, 1. ↵

- Pollard, “Canadian Energy Policy in 1985: Toward a Renewed Federalism?,” 164. ↵

- Ibid., 164. ↵

- CBC. “Pierre Trudeau Not Worried About Western Alienation in 1969.” Thursday Night TV, 3 October 1969. ↵

- Ovenden, “Now THIS Was a Tax Revolt; When Pierre Trudeau Decided to Redistribute the Country’s Oil Wealth, Alberta Really Got Mad,” 3. ↵

- Canada, Official Report of the Debates of the House of Commons of the Dominion of Canada: First Session–Thirty-Second Parliament, 29 Elizabeth II, 1980. Ottawa, ON: Hon. Jeanne Sauvé, Queen’s Printer for Canada, 1980. P.34-35. ↵

- Ovenden, “Now THIS Was a Tax Revolt; When Pierre Trudeau Decided to Redistribute the Country’s Oil Wealth, Alberta Really Got Mad: FINAL Edition,” 3. ↵

- Pollard, “Canadian Energy Policy in 1985: Toward a Renewed Federalism?,” 167. ↵

- Energy, Mines, and Resources Canada. The National Energy Program. 1980. ↵

- John English, “TRUDEAU, PIERRE ELLIOTT,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 22, University of Toronto/Université Laval, Quebec. 2003. ↵

- David Frum, “The Disastrous Legacy of Pierre Elliott Trudeau; From Cozying up to Dictators to Alienating Washington to the NEP, Trudeau Created a Trail of Wreckage That’s Taken Three Decades to Clean Up.” National Post. 2011, 2. ↵

- Political Database of the Americas (1999) Canada: 1984 Parliamentary Election Results. [Internet]. Georgetown University and the Organization of American States. ↵

- Ovenden, “Now THIS Was a Tax Revolt; When Pierre Trudeau Decided to Redistribute the Country’s Oil Wealth, Alberta Really Got Mad: FINAL Edition,” 2. ↵

- Ibid., 4. ↵