The full cycle of emergency management involves 4 phases :

- Prevention and mitigation (based on risk management)

- Preparedness (including a comprehensive plan, training, and practice exercises)

- Response activities (examples of incident command and triage)

- Recovery and business continuity

The first section covers prevention and mitigation. This section will focus on the preparedness stage of emergency management. Nursing leaders are typically very involved in this stage given the need to plan based on knowledge of the patients and the work of providing care in that setting. In addition, the need for training and practice is essential for nurses, particularly in environments such as hospitals when nurses have extended leadership responsibilities on weekends and shifts.

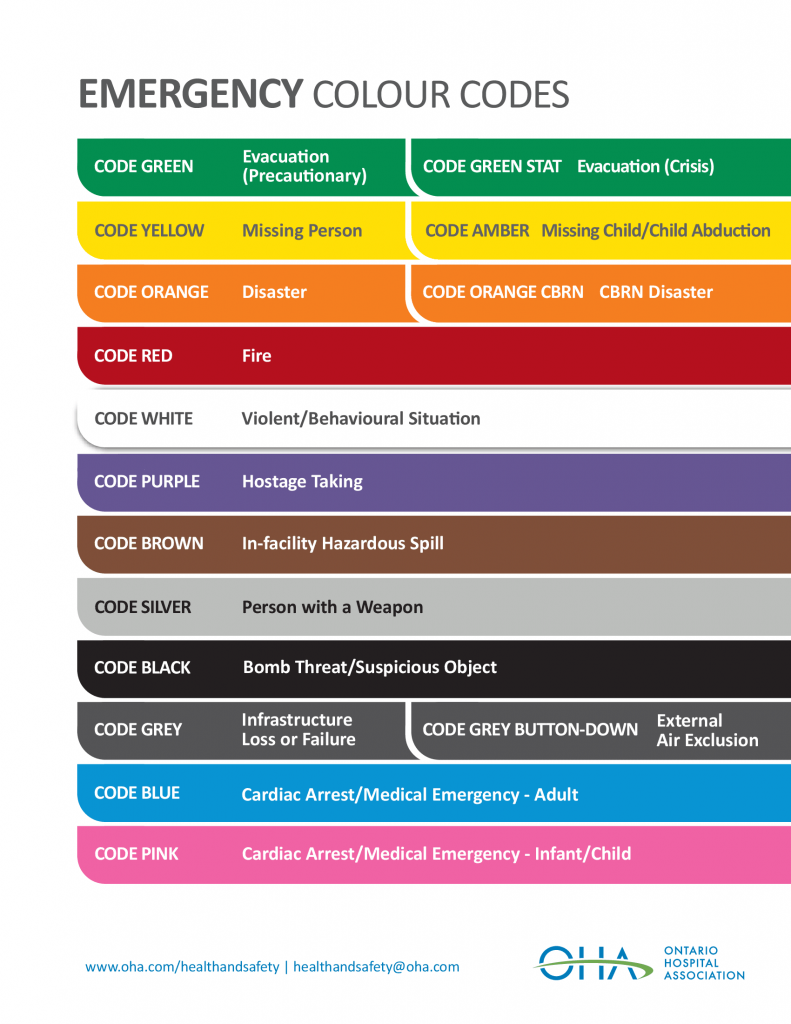

One familiar framework for emergency preparedness at the clinical level is the system of standardized Emergency Codes in Ontario hospitals. Below is an example of a tag that is worn with the staff identification badge. An emergency code can be communicated by using its associated colour. The term Code Blue is widely familiar to denote a cardiac arrest while Code Red denotes fire. These are examples of risks (largely based on significant impact) in the hospital setting that require coordinated organizational responses that are planned and documented in policy. These “code” responses are associated with education, training, and practice sessions to ensure the planned mitigations have the best chance for success when the need arises. Fire drills and evacuation drills for example are an important part of emergency preparedness. In addition, such drill practice is a standard for Accreditation Canada.

Click the image below for a larger view of the Emergency Colour Codes list in a new window

Additional standardized emergency codes include a colour (purple or silver) which indicates an active shooter or active weapon. This situation, like the other codes, relates to a planned coordinated response by the staff involved, the organization and relevant community partners such as police and fire.

Activity #1

Below is an actual headline of an emergency incident in 2017.

Elderly couple dead after shooting at Cobourg hospital, SIU investigating

Activity #2

After reading the above article, and as a nurse leader, think about your organization / work situation and consider what factors could contribute to increasing the risk of harm/impact.

Think about the four elements of risk management and what plans you recommend to reduce potential harms.

Some examples of elements to consider might be:

- Access and exits

- Initiating the code response

- Safety

- Other patients in the area

- Other staff in the area,

- Should other staff come to help?

- Police response time

- Emotional support / recovery

Activity #3

Now think about the training and practice exercises that would support preparedness.

Note that Accreditation Canada requires preparedness to be practiced on all shifts to ensure that plans are tested and practiced in all resource situations.

Code Orange

Another key emergency code response is Orange – for external disaster.

A disaster is a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses and impacts, which exceed the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources (Hammond, Ardon, Gebie, Hutton, 2012). A disaster is, simply put, a catastrophic event that overwhelms available resources. (source Emergency Preparedness and Response chapter 13 by Yvonne Harris in Leadership and Influencing Change in Nursing). Disasters can be natural, such as floods, wildfires, tornados but can also be related to human activity such as rail/ transit, or large space motor vehicle accidents, riots, or other acts of violence.

Within a hospital organization, the risk assessment and planning for external disaster requires an extensive organizational plan that includes notification processes, staff fan outs (call ins), coordination with emergency first responders, triage of casualties, decontamination (potentially), opening additional spaces, decanting/pausing of other activity, if possible, staff deployment, family relations, press relations and communications, and recovery/stabilization.

To begin, the organization will need to consider hazard identification. Being near a large body of water or dam, for example, would suggest that flood is a hazard. The risk may be high or low depending on the local situation. Another example might be a hospital next to a rail line or a major highway. The hazards from this transportation activity can be identified and then assessed. For example, are dangerous goods frequently transported along this route? Risks that could be likely to result in significant harm will need mitigation plans. While elimination or substitution of the risk of rail or highway activity is not possible, there may be some engineered or administrative controls that serve to reduce the risk’s likelihood or impact. An example might be a decontamination unit may be useful if hazardous chemicals are frequently transported on the rail line. An administrative control example may be trauma response protocols for the hospital near the highway.

A disaster response, by definition, however, exceeds the available resources of an organization. Therefore, in examining disaster mitigation, there are a number of other agencies with various responsibilities in these large-scale events. In the next few sections, you will be introduced to this larger context of disaster mitigation.

Activity #4

Read this article about the impact on patients and nursing staff during the evacuation of the hospital during the Fort McMurray wildfire disaster in 2016.

Hospital heroes get patients to safety during Fort McMurray fire

As you read this article, you may have observed that there were many layers of response to this disaster and other significant disasters. Many services were needed, and layers of government had to be involved and therefore coordinated. The following section may seem a bit dry but is an important overview of different levels of government with roles and responsibilities for preparedness and response to large scale disasters. It is also helpful to keep in mind that many organizations and layers of governments will have their own planning and preparedness programs.

The Ontario Hospital Association has a comprehensive toolkit which you may appreciate if you are interested in more details. It is from 2008 so some elements are outdated (such as the role of the LHIN as opposed to Ontario Health) but in general, the concepts still hold true.

Review the figure on page 5 of the OHA tool kit to understand the roles and responsibilities of different levels of government for preparedness and response to emergencies.

The key point to remember is that emergency management, for disasters that impact the community, will involve multiple partners and various levels of command. It will be useful to understand these plans in your home and work communities as well as have some familiarity with the ‘higher level’ federal and provincial plans. The Federal and Provincial planning frameworks are conceptually useful and are discussed in the section below.

There are two key federal agencies for the healthcare sector:

The primary agency is Public Safety Canada.

Through collaboration with provinces and territories to support communities when disasters strike, An Emergency Management Framework for Canada was revised and approved in 2017. “The Framework establishes a common approach for a range of collaborative emergency management initiatives in support of safe and resilient communities.”

This framework is the source document for the four pillars of emergency management:

- Prevention and mitigation (based on risk management)

- Preparedness (including a comprehensive plan, training, and practice exercises)

- Response activities (examples of incident command and triage)

- Recovery and business continuity.

It is also the basis for The Emergency Management Planning Guide which provides step-by-step instructions of the planning process across the four pillars of Emergency Management.

The second relevant agency for health care is the Public Health Agency of Canada.

The Public Health Agency of Canada is part of the federal health portfolio. Its activities are focused on preventing disease and injuries, responding to public health threats, promoting good physical and mental health, and providing information to support informed decision making. The website is useful for links to other agencies and plans. In particular, it has emergency preparedness and response information related to Pandemic Plans (for influenza) and Chemical Biological Radiological Nuclear (CBRN) events.

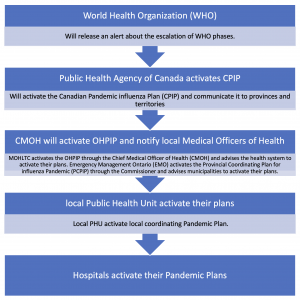

You will have some very current familiarity with the layers of responsibility for response during the recent COVID pandemic. Below is a graphic representation of this cascade of responsibility, again from the OHA toolkit.

In Ontario, the Ministry of the Solicitor General has responsibility for the emergency management plan.

At the government level, all municipalities and provincial ministries are required to have an emergency management program. The Ontario plan and the Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act instructs municipalities/communities on processes for planning in their own jurisdictions. As you now know, the process begins with identifying hazards and conducting a risk assessment based on community knowledge of assets and capacity, critical infrastructure and unique hazards.

Most incidents that occur are handled at the local level by well-trained emergency responders. In the event of a larger incident, the head of municipal council may decide to declare an emergency and assemble local officials at the municipal Emergency Operations Centre. This approach ensures a coordinated and effective strategic response. Hospitals and other health provider agencies can be invited to these tables, particularly if there are anticipated casualties/ victims. This concept of an Emergency Operation Centre or Incident Command Structure is one that is echoed in most emergency management plans at the organizational level. More about this in the next section.