There are two approaches to change – planned and linear and non-linear. The linear approach to change is best suited to less complex, incremental change although there are many examples of complex change for which linear models have been used. An example of a less complex change might be implementing staff development to teach nurses about a new IV pump for instance. Change agents involved in planned or linear change are focused on the specific goals and incremental steps that are required in order to meet those goals.

Changes that are more complex and more susceptible to change over time are more suited to a nonlinear approach to managing change. Nonlinear approaches to change management include chaos and learning organisation theories. These approaches are best suited for guiding change in complex and uncertain change environments. Change agents involved in complex nonlinear change will act as monitors of the situation, negotiating the influences on a change and forecasting the possible approaches to managing the change and the outcomes that can be anticipated.

Harrison et al. (2021) conducted a systematic review of publications of studies related to change management in health care. They identified and included 38 studies in this review of which 29 were conducted in hospitals. Kotter’s (2012) model was used most frequently (19 settings) with Lewin’s (1947) three-stage model used in 11. The authors were unable to determine whether use of a particular model contributed to the success in making the change, but they remind us that change management models can provide a guiding framework for change as opposed to being prescriptive. This is consistent with health care being part of a complex, adaptive system. The authors conclude that when these models are adopted in a flexible manner which is adapted to the context in which they are being used they can be “used to complement and support improvement and implementation methodologies”.

Change Management Theories/Models

In this section, you will learn more about some of the more commonly used change management theories. These include both linear and non-linear change models.

Activity #1

To provide some background for these theories and their application, read Chapter 9 in Common Change Theories and Application to Different Nursing Situations, pages 156-167 (to the end of section 9.6).

Wagner, J. (Ed.). (2018). Leadership and Influencing Change in Nursing. Regina, SK: URPress.

Linear approaches to change

There are numerous linear change management theories. We will focus on Lewin’s three step model (1947), Lippitt, Watson and Wesley (1958), Roger’s innovation decision process (1962), Havelock (1973), and Kotter’s 8-step process for leading change (2012). These theories are described by Udod and Wagner (2018).

Lewin (1947) proposed a model that includes three stages: unfreezing, experiencing the change, and refreezing. Lewin also suggested that the change situation be analysed using what he labelled as a force field analysis done both early and as an ongoing assessment of the barriers and the facilitators to the change process.

Activity #2

Watch the following short video about Lewin’s model.

Video: Lewin, Stage Model of Change Unfreezing Changing Refreezing Animated Part 5 (8:07)

Lippitt, Watson and Wesley (1958) built on Lewin’s work but focused more on the actions of the change agent than the change process. They proposed that change can be planned, implemented, and evaluated sequentially over seven phases and that ongoing sensitivity to the forces, present in the change process, is essential for success. Udod and Wagner in Wagner (2018) describe are seven steps in this planned change model :

(1) diagnosing the problem; (2) assessing the motivation and capacity for change in the system; (3) assessing the resources and motivation of the change agent; (4) establishing change objectives and strategies; (5) determining the role of the change agent; (6) maintaining the change; and (7) gradually terminating the helping relationship as the change becomes part of the organisational culture.

In Roger’s innovation decision process (1962) model, change occurs over five phases and in each phase, individuals choose to accept or reject the change (innovation). This model is more focused on individual than organisational change.

Activity #3

Watch the following short video about Roger’s innovation decision model.

Video: Rogers’ Five Stages of Innovation – Decision Process (4:31)

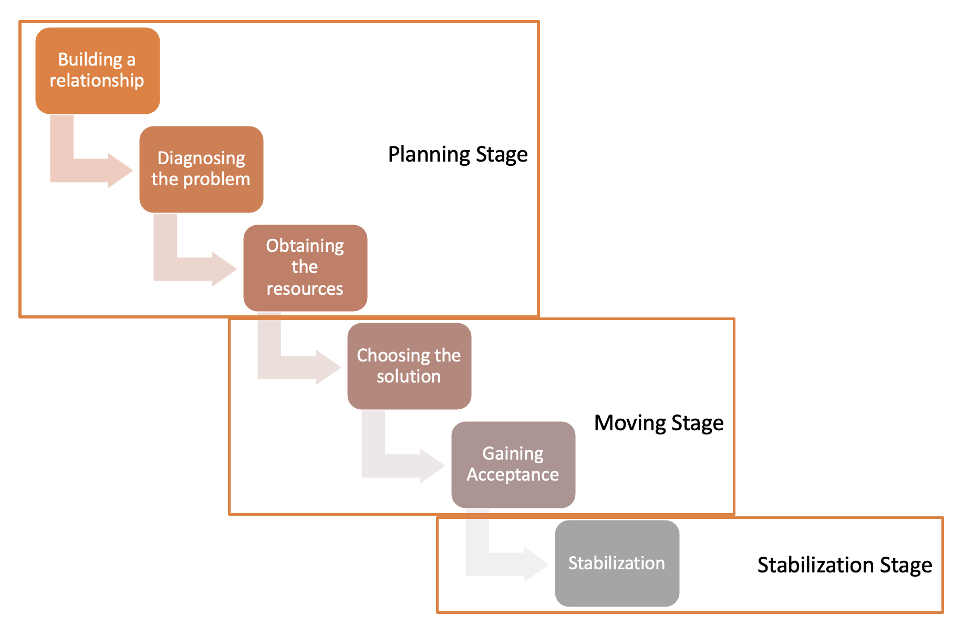

Some years later, Havelock (1973), again building on Lewin’s work, proposed a six stage model for planned change. This model was particularly applicable to educational situations but can be used in other types of organisations. The first three stages (Figure 1) comprise the planning stage of change. This involves developing a relationship with the organisation/system in which the change will occur; determining whether the proposed change is needed or desired (diagnosis) and collecting the information that is needed to undertake the change (obtaining the resources). This is followed by the moving stage which includes determining the strategy/solution for implementing the change and accepting and adapting the chosen solution (gaining acceptance). The sixth and final stage is the stabilisation phase. This occurs once the change has been made and entails monitoring to ensure that the change is maintained.

Kotter’s 8-step process for leading change was the model most frequently used in Harrison et al’s (2021) systematic review of the application of change management models in health care.

The eight steps in this model are:

- Creating a sense of urgency

- Building a guiding coalition

- Forming a strategic vision and initiatives

- Enlisting a volunteer army

- Enabling action by removing barriers

- Generating short-term wins

- Sustaining acceleration, and

- Instituting change

Activity #4

Watch the short video explaining Kotter’s 8-step process.

Video: Kotter’s 8-Step Change Model Explained (10:15)

You can also download Kotter’s 8 Steps to Accelerate Change (Updated for a COVID world) eBook.

Nonlinear change models

Most organisations perceive change as linear and sequential. While linear models of change continue to dominate in health care organisations there is a growing awareness that non-linear change models may be more appropriate for instituting complex changes in open systems. There are a number of nonlinear approaches to change; we will review two: chaos theory and learning organisation theory.

Chaos theory – Chaos theory originated in the 1960’s in the field of meteorology and started to appear in management literature in the 1980’s (Radu et al, 2014). Chaos theory has been defined as “the qualitative study of unstable, aperiodic behaviour in deterministic nonlinear dynamical systems” (Kellert, 1992). Stacey et al (2002) argue that “ “For organisations, as for natural systems, the key to survival is to develop rules which are capable of keeping an organisation operating ‘on the edge of chaos’”.

In chaos theory, it is proposed that an emphasis on rules and policies is short-sighted, a waste of time and likely to lead to failure to accomplish change goals. This is because changes occur in open systems which are subject to many internal and external influences. Instead, according to chaos theory, there should be an emphasis on adaptability, initiative, and creativity. Typically, organisations experience periods of stability which are interrupted by spurts of change or transformation as opposed to experiencing constant, predictable, incremental change. The future is often unpredictable and, according to chaos theory, the conditions that are present in one organisational change process or situation are unlikely to occur in the same form in future situations.

The implications of using chaos theory to support the change process are:

- Managers need to learn how to manage in changing contexts, need to promote self-organising processes and learn how to use small changes to create large effects (Morgan, 1997); this involves managers thinking less traditionally about hierarchy and control.

- Managers need to encourage experimentation, as well as divergent views.

- There is a need for greater democracy and power equalisation in the organisation which includes proposing structures, policies and practises that create the conditions for self-organisation. This includes a balance between self-organisation and the need for some “order-generating” rules.

- There should be a recognition that change that is continuous and based on self-organisation at the team level (as opposed to small-scale incremental or radical transformational change).

Chaos theory may help organisations to understand why change is so challenging and provide an approach for overcoming the challenges.

Learning organisation theory – Flexibility and responsiveness are emphasised in learning organisations. Organisations that use a learning approach are responsive to internal and external influences in the context of a typically unpredictable healthcare environment. Change management in a learning organisation is based on a continuous development process. Changes take place through learning processes that all staff participate in.

Activity #5

Watch this short video on learning organisations. It is a good overview of what a learning organisation is and the implications for both change and change management.

Video: The Learning Organization (4:02)

The concept of learning organisations was outlined by Senge in his book called The Fifth Discipline (1990). In this text he outlined five disciplines that he considered essential for learning organisations. These are 1) systems thinking, 2) personal mastery, 3) mental models, 4) shared vision and 5) team learning. The learning organisation concept can, and has been, applied to a range of health care organisational units including hospitals and primary care (Etheredge, 2007).

Learning health systems (LHS) are health systems in which knowledge generation systems are embedded just as they are in learning organisations. They lead to a natural integration of research (new knowledge) into patient care and practice promoting innovation as well as safe, high quality health care (Melder et al, 2020). The National Academy of Medicine (NAM) defines a learning health care system as “one in which science, informatics, incentives, and culture are aligned for continuous improvement, innovation, and equity – with best practises and discovery seamlessly embedded in the delivery process, individuals and families active participants in all elements, and new knowledge generated as an integral by-product of the delivery experience.”

A Canadian example of a learning health system is EPIC which stands for equity, performance, improvement, and change. The Alliance for Healthier Communities is a membership driven organisation representing and supporting community-governed primary health care organisations in Ontario. EPIC is a relatively new LHS which brings together a range of Alliance programs and projects to generate new evidence, change and improve practice.

A comprehensive learning health system:

- “spans disease prevention, cure, and management”

- “builds on advances from genomics to social determinants”

- “takes advantage of discoveries at all levels of biomedicine and public health”

- “uses ever-expanding data systems and capacities for analysis and interpretation”

- “functions at both population and individual levels”

- “works collaboratively across institutions and constituencies”

- “constantly scans and uncovers opportunities for real-time improvement in the experience, cost, and outcomes of care”

~ McGinnis et al, 2021

The COVID 19 pandemic, with the accompanying healthcare, emergency response and public health management changes, has tested the system’s capacity for change and change management while making clear the need for learning health systems. The most up to date evidence has been needed in practice as soon as it is available instead of the reputed 17 years that it takes for research evidence to reach clinical practice (Morris et al, 2011). Learning health systems, which were created to facilitate the uptake of the newest evidence, from multiple sources, into practice are an obvious way to learn from every health care provider, researcher and patient that enters the system in order to improve care for future patients.

Change and change management have traditionally been seen as one-time, linear implementations of a change. These changes could be as simple as a new IV pump or as challenging as a new electronic health record system across all units and care providers in a large health care facility. They could also occur at the level of a unit, across an organisation or across a health care system. Linear approaches to change management continue to dominate and have been successfully used to make both simple and complex changes at multiple levels. There is a growing awareness, and this has been highlighted by the rapid, complex, multi-level and system changes wrought by COVID 19, that non-linear change models may be better suited to change in open systems which tends to be complex and continuous.

Check Your Understanding