10. “A new attitude” – Recovery, Part 5

To exist is to change, to change is to mature, to mature is to go on creating oneself endlessly.

This quotation by the 20th-century French philosopher Henri Bergson gives you a glimpse of what was going on in my life in February 2022, dear reader.

“It does?” asked my main guide after I had typed the above sentence (five months later.)

“Yes,” answered “Barb 2.0”. “No,” argued “Dr. Barb”.

Much to my frustration, two long-term symptoms – IBS issues and vaginal burning – had returned.

“And we know what that means,” my top-hatted guide was quick to point out.

“Get all of your @#$% together now,” my “inner crew” recited in unison.

“That’s easier said than done.”

It damn near killed me

“My sincere apologies.”

I was addressing my “Zoom audience,” as in university students and colleagues, on a Wednesday afternoon in early February.

My Wi-Fi connection had suddenly gone horribly wonky. In fact, it got so bad during class that I ended up typing like mad in the chat to offer comments on my (undoubtedly riveting) PowerPoint slides. In hindsight, I probably sounded like I was participating in a séance of sorts (“Can you hear me now?”).

Fortunately, my colleague with whose mother I shared a cancer diagnosis was there “to save my butt” (to use a colloquial phrase.)

“Can we please chat on the phone after class today?” I asked my colleague after letting the students out early.

“What’s on your mind, Barb?”

I took a deep breath and decided to be brutally honest: “I feel overwhelmed,” I told her.

Then I admitted that I had been asking too much of myself and of the students. To my surprise, my colleague echoed my concerns (“I feel the same way.”)

What was it with academics and the need to push themselves and others 24/7?

I still remember how much I had welcomed the publication of the book The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy by Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber in 2016. I had been promoted to full professor, the top professorial rank at my university, that July.

Putting together what felt like 500 pages of supporting materials in autumn 2015 and asking various esteemed colleagues to write reference letters for me – “Would this individual also meet the criteria for full professor at your institution?” – had been a nightmare, to put it mildly.

“It pretty much sucked the life out of you,” my top-hatted guide stated, matter of fact.

“It damn near killed me,” countered “Dr. Barb”, unexpectedly dramatic (for an academic.)

Was she perhaps channeling her usual “blunt self,” a trait often associated with Germans? Yet, my trusted neighbour also typically offered an honest opinion despite being of a different ethnic background.

Could I have waited to apply or, fearful of being rejected, not applied at all for promotion? Of course.

“Be prepared to work much harder for much longer than your male counterparts, Barb,” I had been told early on in my career by two female university professors. “Sexism in academia is real, if not rampant.”

So, I worked hard all the time to impress “Dr. Barb” and my “scholarly ego” (aka my inner workaholic.) Both argued incessantly – and successfully – that it was “fun” and “so worth it” to push myself non-stop (their words, not mine.)

No wonder that I adopted a similar approach when faced with the task of healing from a medical ordeal.

On a different note, the ongoing racism, visible and invisible, at post-secondary institutions is another, continuing topic of concern in my world.

I will never forget how excited I was when my beloved roommate from India had been accepted to an Ivy League university in the United States for her Ph.D. degree in musicology (“I got a free ride, Barb.”)

My dear friend did not last long, however.

Certain faculty members felt strongly that she should change her academic focus from Western Classical music to ethnomusicology and become an expert on Bollywood music (“You’d be perfect!”).

Fed up, she switched universities and continents, only to experience more of the same overseas. She did get her doctoral degree eventually, but under duress (for lack of a better term.)

I was still “too young and too stupid” at the time (to quote “Dr. Barb”) to grasp fully how privileged I was as a Caucasian female, albeit with a slight accent (“Are you from Quebec?”).

But I could not get a permanent job either, despite my stellar CV and excellent pedagogical skills.

What was the problem? Long story short: I was “too German” – and had (distracting?) breasts as well as a vagina.

Yet, for one particular job at an Ivy League school in the United States that shall remain nameless, I was “not German enough” and, of course, lacked a certain male appendage.

“Seriously, you applied for my job, and they chose me over you?” the male who had been offered and accepted the post asked me many years later.

“I am kind of glad it didn’t work out,” I said, still feeling relieved. “It allowed me to stay in Canada near my family and flourish beyond my wildest dreams.”

While that was true (thank you, Saskatchewan), in early 2017 I ended up ignoring the valuable suggestions made by the authors of The Slow Professor, specifically to not engage in an academic race of sorts.

“There’s nothing wrong with that,” my “scholarly ego”-self stated confidently. She was still having way too much fun excelling at my professorial duties, to put it mildly.

“I cannot keep this crazy pace up much longer,” an exhausted “Dr. Barb” admitted in late 2017.

Co-editing a huge (as in 432-page and bilingual) conference report in record time while carrying a full teaching load and doing a lot of administrative work on top of it, had taken a huge toll on me. In contrast, my “scholarly ego” was beaming non-stop.

“What are you going to say no to from now on?”

My best friend, sounding concerned, had asked me this loaded question in spring 2018.

“I’ll cut down on my work hours and take off more Sundays playing the organ at my church,” I promised, feeling confident.

Instead, I used all this extra time to exercise at the local pool, telling myself that I was improving my work-life balance but also keeping off all the weight I had lost throughout 2018.

In January 2019, a stressed “Dr. Barb” and a weary top-hatted guide threatened to shoot my “scholarly ego” unless she agreed to back off.

“If not, I will make you gain 100 pounds back in record time,” my inner child added, sounding similarly serious.

Then the universe itself (?!) sent me a never-to-be-forgotten signal to slow down in earnest.

In March 2019, a beloved colleague in his early 40s suddenly committed suicide. Could the sky-high expectations of academic life have played a role in that individual’s decision to take their own life, I wondered?

While I did not know the answer, I knew that my world had changed forever because of what had happened.

Grief-stricken, I did something positively radical in response a month later: I stepped down as the vice-president of the German non-profit music society for which I had worked in the late 1990s.

It was a huge deal for me. I had been heavily – and, for the most part, happily – involved with them ever since choosing a suitable topic for my Ph.D. dissertation in the early 1990s.

After all, we shared the same mission; that is, to promote the life and works of J. F. Fasch on a global scale.

“I am not leaving you,” I declared at the society’s annual general meeting. “I am just taking a break.”

Specifically, I would stay on their Executive Board as a member-at-large but take off some time to write a long overdue scholarly monograph about my favourite 18th-century Kapellmeister and German court musician.

However, it took a sudden cancer diagnosis and an extended medical leave for me to realize what I had really done, namely fallen into a “scholarly ego trap” of sorts.

“You better write that Fasch book before someone else beats you to it,” was the line I kept hearing in my head – and I believed it.

In retrospect, I should have realized that my head had “taken me where my body should never have gone” (to quote my pastor-friend.)

When typing up this sentence in June 2022, a memory clip began playing in my head.

After my momentous “Count me out – at least for a while” announcement, I went back to “Fasch land” in the summer of 2019 to carry out more research for “the book.” (The amount of flying overseas I used to do in pre-pandemic times now boggles the mind.)

“Fasch land” (as “Dr. Barb” would call it) is a small town in Central Germany. During the two and a half years I had lived and worked there in the late 1990s after finishing my Ph.D. degree, many people had talked behind my back. (“Why would they hire a West German who lives in Canada for a position that should have gone to an East German?”).

A dear friend from my German post-doc days had called and invited me over for tea.

“So, you didn’t step down from the Board because you had been seriously ill, Barbara?”

“I have never felt better,” I said.

Granted, my weight loss journey with Weight Watchers had been so dramatic, as in 75 pounds less on the scale, that some locals in “Fasch land” had not recognized me (“You are too thin now.”)

“That’s good to know,” my friend replied. Then it began to dawn on me.

“What have you heard?” I pretended to be amused. Evidently, the local rumour mill was still alive and well two decades later.

Before my friend responded to my – admittedly loaded – question, I noticed that my inner child began to feel extremely unsettled, and for good reason.

Several months after losing our mom in January 1985, my twin sister and I heard a nasty piece of gossip.

Our beloved parent had apparently “committed suicide” (“What?!”) because her “much younger boyfriend” had “rejected” her (“OMG!”).

Worst of all, the person in question had “dared to attend the funeral.” Could this, um, special individual have, in fact, been our uncle who was 12 years younger than his late sister?

“Barbara, when you showed up a couple of months ago in town, looking like a million bucks, some folks said that it had come at a steep price,” my friend explained.

I was stunned, to say the least. Who were these, um, all-knowing individuals?

“They said that you had lost all that weight while undergoing cancer treatments.”

After picking my jaw up from the floor, I quickly reassured my friend that I was “perfectly healthy.”

In hindsight, I was impressed with the crystal ball to which “these people” had access. Maybe I should have done some detective work to find out their identities and ask them to tell me more about my future?

Incidentally, it was not lost on my own “inner fortune teller” (for lack of a better label) that instead of producing a lengthy academic book about someone who had been dead as a door nail for centuries (since 1758, to be exact), I wrote a memoir about a person who was still very much alive.

Would Herr Fasch, the “love of my academic life” (to quote “Dr. Barb”) ever forgive me for, well, “ditching him” (to quote “Barb 2.0”) in favour of my health, I wondered?

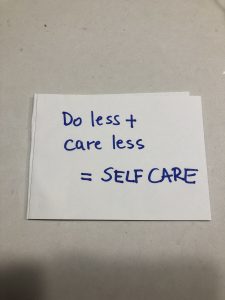

Self care matters

“If you have a sense already of how to adjust the workload for the rest of this semester, please let me know, Barb,” my colleague said, bringing me back to the present; that is, early February 2022.

“Yes – I’ll figure out a ‘course correction’ that will work for everyone.”

Thanks to the excellent input of “Dr. Barb” and “Barb 2.0”, I proposed a revised and much more balanced class schedule to my colleague the very next day.

The following Wednesday, I informed the students about the proposed changes and asked for their official consent. I was not surprised when they all said yes.

“Before I begin lecturing about music-related topics today, I’d like to spend 20 minutes talking about mental health, including my own,” I announced, and started sharing my screen.

As anyone who knows me will attest to, I am an individual blessed with a cheerful disposition and optimistic outlook on life.

But I had been no stranger to depression, nor had other family members been immune to it. (According to my mother, one of her aunts had once jumped out of a window during a particularly distressing mental health episode.)

“How many of you are familiar with the Mental Health Continuum Model (“Healthy – Reacting – Injured – Ill”)?”

It quickly became obvious that some students had never heard of it.

I had first become aware of it before the pandemic when my best friend had completed a Mental Health First Aid course; the same topic had also been the focus of a recent pre-semester retreat at work.

After touching on my own mental health struggles over the years, including during my active cancer treatments, I closed with a request.

“Please do a self-check regularly by asking yourself ‘Where am I right now on the mental health continuum?’ – and then make changes accordingly.”

My colleague chimed in to emphasize that the two of us had done “just that” after last week’s class.

In fact, after our heart-to-heart-talk, I had happily thrown out a half-empty jar of Nutella (“I am officially done with you.”) My inner child was appalled, of course, and promptly disappeared to sulk.

“In other words, we reached out to each other before we got to the ‘injured’ or ‘ill’ stages,” I clarified. My colleague nodded into her camera to signal her agreement.

“I hope you will come to talk to us as well – our virtual office doors are always open.”

I was grateful when one student did approach me after class about what had been said (“Thank you for reminding me what’s important in life!”).

The very next day, my twin sister shared some of her own concerns about a troubling work matter.

“I can help you with that,” I declared confidently. “I have devised a ‘how to live your life from now on’ formula.”

“But you are really bad at math,” my twin sister emphasized, laughing at me.

I knew what she was thinking. At the beginning of Grade 12, I had scared my mother and myself by failing an important calculus test even though I had studied for it and even seen a (somewhat creepy) tutor for help.

“Let me guess,” my mom had said when I told her about my less than stellar performance. “You got really anxious and could not remember a thing?”

I nodded and assured her that I was going to do my very best to graduate from high school despite of what had happened. (Little did I know at the time that she would not be there to celebrate that important milestone with me.)

For the record, my math exam anxiety had been going on since Grade 5 when my twin sister and I had switched to the Gymnasium.

This type of German secondary school is the only one that allows you to enter university immediately after graduation.

The highly competitive learning environment catered toward gifted teenagers who excelled at memorization. (A world without having Dr. Google and Mrs. Wikipedia right at your fingertips? Imagine the concept.)

“Would the girls be interested in taking the required aptitude test?” our mother’s best friend had wondered when we were in Grade 4.

Her daughter was keen on giving it a try; we were not. We passed; she did not.

In hindsight, math had always been a nailbiter for me, especially in Grade 10. To be told all year long (!) by a – very unsympathetic – teacher that I was “a lost cause” had been tough, let me tell you.

Yet, my mother knew I wasn’t stupid and a hard worker to boot.

My grades in the other 13 (!) subjects in Grade 11 – I was in the “foreign languages” stream and excelled in German literature, history, music, and art as well – had ranged from “very good” to “satisfactory.” (“Whatever that meant at the time,” my inner child was quick to point out.)

My late mother likely rejoiced in heaven when I managed to pass Grade 12 math thanks to a – very kind and caring – teacher (“You can do this, Barbara!”).

Now the time had come to convince my younger sibling that I had moved past my math phobia.

“My very own ‘life formula’ does indeed contain a plus and an equal sign,” I explained. “But that’s about it.”

Then I flipped my phone’s camera so she could see what I had printed on a piece of paper.

As an experienced instructor and predominantly auditory learner, I read it out loud as well so she would be able to remember it better.

“It says ‘Do less plus care less equals self care’.”

A question mark appeared on my twin sister’s face in slow motion.

“Caring less does not mean that you are careless about it,” I clarified. “Self care is about your attitude toward something or someone, not your reaction.”

I shared my newly acquired wisdom of sorts with my pastor-friend a few days later as well.

“How did you come up with this compelling equation, Barb?” I could hear her smile through the phone.

“I have always been intrigued by a quotation attributed to Albert Einstein.”

“Are you referring to ‘Imagination is more important than knowledge’?”

A poster with that witticism had graced the walls of my home office throughout my years as a graduate student in the 1990s.

“No, another good one: ‘Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results’.”

“Ain’t that the truth, Barb.”

Of course, the challenge would be to remember to apply this new formula consistently.

“If nothing else, it will help you to feel more settled as you navigate uncharted waters now, and in the future,” my top-hatted guide stressed when I went to bed that night.

“That’s right,” I admitted. Because at the end of every day, I aim to please.

The Little Mermaid

“Thanks for working your magic on my ankle – again,” I said to my Reiki-master friend in late February 2022.

She had come over for another visit. This was, in fact, the third Saturday in a row that she had massaged both my ankles, for which I was so very thankful.

“I have really noticed a difference.” I was smiling at her. “I can literally feel the healing that is taking place inside my feet when you touch them.”

“But your toes still look pretty beat up, and they are really tight, Barb.”

Then I suddenly started laughing like crazy.

“What’s so funny?”

“Nothing – I am just ticklish everywhere, and not just on my feet.”

My trusted hairdresser knew all about it and smiled every time I told her to use lukewarm water to wash my hair to prevent a “giggle attack” (my words, not hers.)

In hindsight, I realized that the urge to laugh uncontrollably when someone touched me had first begun when I entered perimenopause in my mid-40s. Interestingly, it never happened when my trusted massage therapist worked on me (“You are very connected inside your body, Barb.”)

“Do you want me to come over next Saturday as well for a repeat performance, Barb?” My Reiki-master friend was cleaning her hands after the treatment.

Albeit touched by her offer, I respectfully declined because I already had other plans.

Long-time friends from Regina were in town: my fellow IBS sufferer friend and her wonderful older sister who I had met at a university workshop shortly after my arrival in the prairies nearly twenty years ago, as in the early 2000s. They had already been over for tea (“Great job on decorating your condo, Barb.”)

“Too bad you are not male and looking for love,” my top-hatted guide had once pointed out to me, much to my amusement. “You would have made a great addition to that lovely family.”

His perceptive comment was arguably a subtle hint at the fact that in the past I tended to like my future parents-in-law more than I liked their sons. (Enough said.)

I was truly looking forward to spending quality time with these “favourite sisters” of mine. Born and raised in Saskatchewan, they were seasoned travellers but unaccustomed to the high humidity.

“You should have told us to bring warmer clothes, Barb,” my friends were quick to scold me.

Intriguingly, this was their first visit to Vancouver Island (“We were told by older relatives that only hippies lived there.”)

I warned them that there would likely be anti-vaccine mandate protesters to deal with during their stay. Rallies typically took place on Saturdays at Victoria’s picturesque Inner Harbour, close to where my friends were going to stay.

“Would you like to join us on a whale watching tour tomorrow afternoon, Barb?”

It was Friday night, and they were going to fly back to the prairies on Sunday morning.

“What is the company’s Covid-19 protocol like?” I asked.

I wanted to know even though proof-of-vaccination status and mask mandates were in place in B.C. until March 11, 2022. In contrast, the Government of Saskatchewan had already dropped these requirements on February 14, Valentine’s Day.

“Masks are required the second you step on the boat,” my friends noted. “And judging from the online reservations, the boat is only half full.”

“Count me in.”

I could feel my inner child getting totally excited, and for good reason. It had been difficult to engage in meaningful social activities for many months now (“Thanks for nothing, Omicron.”)

Granted, I exercised daily, either by following my sister’s routines at home (including online) or when she taught water aerobics. (Unlike in Regina, swimming pools had stayed open in Victoria, even though all rec centres had been shut down from mid-December 2021 to mid-January 2022.)

Taking a class at the yoga studio on Tuesday nights did not appeal to me at all (“Too crowded.”) Instead, I had watched my teacher turn herself into a pretzel on my computer screen once a week for three months in a row (“Remember to breathe.”)

I considered singing in a – socially distanced and fully vaccinated – church choir during worship services on Sunday mornings a tolerable risk. Of course, I wore my mask “religiously” (pun intended), as did everyone else involved.

On the first Saturday in March 2022, a huge crowd of anti-vaccine protesters gathered at the B.C. legislative building in downtown Victoria.

I was glad to see that many police officers kept these noisy folks in check when I walked along the Inner Harbour to meet my friends at their timeshare hotel.

Was I afraid for my life? No. But perhaps my friend was, given that I suddenly saw her running by me, as if being chased by a bear. Was everything alright?

“Yes, of course, Barb.” Her younger sister laughed when I called in a panic to find out what was going on.

Her sibling had been on her way to the Royal British Columbia Museum, specifically to their lovely gift shop.

She was going to get a special pair of gloves for their mom (“Would you mind going back and getting them for me, girls?”); the plan was to be back before I arrived.

What the sisters could not have known was that I had taken an earlier bus to make sure I was going to be knocking on the door of their vacation home in plenty of time.

The girls were also surprised to find out that I had not yet visited the Royal British Columbia Museum.

“We really liked it – you should go before you return to the prairies, Barb,” they said.

For the record, I was shocked when the Government of British Columbia, in their infinite wisdom, unveiled a plan in May 2022 to renovate said museum for 789 million dollars (no joke.) The premier cancelled that plan a month later, after a huge public outcry.

“I did not expect there to be so many people,” I said to my friends when we reached Fisherman’s Wharf and got ready to board the sightseeing boat.

About 50 individuals ranging from kids to seniors had arguably also figured that today was the perfect day for an outing, given the beautiful, sunny weather.

“Welcome on board to our first tour in 2022,” the captain announced proudly through the intercom.

I had been on enough boat rides before to dress in layers as it was going to be cold on the outer decks.

To that end, I wore the same faux fur-lined leggings I loved to don during my radiation therapy treatments in February and March 2021 (“Those look comfy, Barb.”)

I also premiered my new winter coat, a faux fur-lined toque, and a pretty scarf that I had purchased (“for next to nothing,” to quote my twin sister) on Boxing Day.

Insulated winter gloves which I had brought with me from the prairies as well as my trusted hand-knitted wool socks from Germany completed my fashionable “sightseeing look.”

After about 30 minutes travelling along the southern shore of Vancouver Island, my body, mind, and spirit began to relax – with special thanks to the Juan de Fuca Strait. It boasted fantastic views of the Olympic Mountains across the border in Washington State that afternoon.

“I feel alive for the first time since my cancer diagnosis,” I said to “my inner crew” multiple times throughout the three-hour trip on the water.

How could I not, given the wonderful company (“We brought snacks for you, Barb”) and access to knowledgeable naturalists on board (“This is like a floating classroom!”)?

“Look at all these animals,” my inner child said to my top-hatted guide, positively riveted.

She had admired the porpoises, golden eagles, and huge, lazy sea lions, but Ollie the sea otter was her favourite.

Did I mind not seeing any whales that afternoon? No. It would have been a miracle to spot any in early March, as sightings were only guaranteed (“as in 95% to 98%”, the naturalist had said) between May and November.

I could attest to that personally. Over a decade ago, I had invited my twin sister, her two boys, and our oldest sister to join me on our birthday in August (“My treat.”)

We lucked out at the time. There were so many killer whales – that is, Orcas – to admire (from a safe distance, of course), that I knew the universe (and nature) were trying to impress me.

“I totally enjoyed my first real outing this year – you know how much I love the water,” I told my twin sister and my Reiki-master friend later that same evening.

We were sitting in a local high school auditorium, waiting for a musical to begin.

Prior to our arrival, I had quietly wondered how the large cast and crew were going to deal with the Covid-19 restrictions that were still in place in B.C. at the time.

As it turned out, everyone moving about on stage and sitting in the pit was wearing either a face shield or a mask (except for performers who had to blow into their instruments.)

“Have you seen this particular musical before?” my Reiki-master friend had whispered when the overture began to play.

“No, but it sums up how I have been feeling ever since I stepped off that big boat several hours ago.”

Can you guess which show we watched?

The Little Mermaid, of course.

The 50% Barb

On Thursday, March 3, 2022, I was up even earlier than usual, making tea in my condo’s kitchen.

My body had been experiencing annoying “body temperature issues” for the past week. In other words, I was either too hot or too cold, especially at night, and didn’t like it, for obvious reasons.

After doing not one, but two 20-minute meditations to ground and stabilize myself (thank you, Deepak), I got up, took a shower, put on some nice clothes, and had breakfast, in that order.

It was going to be a busy morning for “Dr. Barb” and, as it turned out, “Barb 2.0” as well.

First, I attended the weekly 7 am Zoom meeting that brought together fellow musicologists and performing musicians from all over the world who shared an interest in the life and music of J. S. Bach and his contemporaries.

A British-Swedish colleague and close friend of mine had started these Bach Network “teatimes” in April 2020 as a pandemic mental health booster.

Over time, these one-hour long online chats had morphed into “tell us what’s going on in your world” discussion of sorts. Conversations ranged from highly scholarly and super-focused to hilarious and silly, depending on the general mood of the participants.

Most importantly, these entertaining chats had been beacons of hope throughout my illness.

Of course, they would always ask me the magic sentence: “How are you feeling today, Barb?”

A fellow academic from Warsaw joined us that morning. We were worried about him because we had all been watching the news and wondered about life in the capital of Poland these days.

“Are you personally impacted by the war in Ukraine?” one of us asked bravely.

As the child of two World War II survivors, I had been horrified about the Russian invasion in late February 2022, and the resulting refugee crisis.

Our colleague was fine, but their Ukrainian cleaning lady had wept when the war had broken out.

“She was in much better spirits when I talked to her today,” we were told, because “she was so pleased to see that her fellow Ukrainians were fighting back.” (So was I.)

At the same time, I began having second thoughts about travelling to the UK in person in mid-July to co-organize an international conference and present a paper.

“Sorry, folks, I am not getting on a plane this summer unless it’s going to the prairies,” I wrote to the conference organizers in April.

My “inner crew” was relieved as well, for obvious reasons. By staying put I would not only avoid being exposed to Covid-19, but also steer clear of two of the busiest airports in the world, Toronto and Heathrow.

And there was no way knowing how (badly?) jet lag would affect my still somewhat wonky energy level either.

Then my phone’s alarm clock suddenly went off.

It was an audible reminder to join another Zoom meeting already in progress. Since I had taken the time to put on my favourite earrings and even applied lipstick, it was obviously a special occasion.

“We are very happy to welcome the author of one of our assigned readings, Perfect Timing, to class today,” my English instructor-colleague said to 30+ students.

“Hi, everyone.” Feeling somewhat nervous, I smiled into the camera.

The focus of this first-year English class on Critical Reading and Writing in the winter 2022 semester was “Illness Narratives.”

Consequently, I was mildly confident that most attendees were interested in my cancer story (or at least pretended to be.) Except for my instructor-colleague, everyone else in attendance had turned off their camera and was muted. Was that Morse, his cat, in the background?

“Pets on camera are fine,” noted “Dr. Barb”. (She was arguably still worried about another “underwear incident,” given what had happened in the fall.)

“Barb, I cannot predict how chatty my students are going to be on Thursday,” this experienced lecturer with a hilarious sense of humour had written in an earlier e-mail. “How about we approach the 60 minutes we’ve got like a ‘book talk’?”

“That’s fine with me.”

The “plan” was for him to ask me to elaborate on some of the “Leading Reading Questions” posed in my book’s Appendix. Then, we would open the floor to the students for more questions.

To that end, I had prepared a few PowerPoint slides that included images not featured in Perfect Timing. One was my official Grade 1 photo that always makes my inner child grin; I hope you like it, too.

“Before we get started, folks, I’d like a show of electronic hands as to who has read my memoir or started on it.”

To my delight, many screens lit up.

“You do realize that some of them are not telling the truth, right?” asked “Dr. Barb”, albeit only in my head.

I smiled. It was wonderful being back in the classroom, and I did not mind one bit that it was a virtual one and not my own.

The most memorable question my instructor-colleague posed that morning concerned the so-called “Supergirl’s Creed” poem.

I had examined this funny German three-liner in the Epilogue chapter of Perfect Timing. Here it is again in English translation:

The impossible we attend to immediately.

Miracles take a little longer.

Upon request, witchcraft will be used.

And here is what else I had written about it:

These three lines arguably captured my approach to life in general before my cancer surgery in August 2020. It touched on the what (“the impossible,” “miracles”); the when (“immediately,” “a little longer,” “upon request”); and the how (“attend to,” “witchcraft”).

“Barb, since writing the book and thinking more about it, how have the categories of impossible, miracles, and witchcraft, shifted – what are they now?”

To my complete surprise, my health guide, “Barb 2.0”, jumped right in, without hesitation.

“I attend to the possible today,” she said.

“Miracles are no longer required,” she added.

“Witchcraft, that is, prayers, are used daily to keep me going,” she emphasized.

“You should have these three sentences tattooed on your forehead or some other place of your anatomy that’s hard to miss,” my top-hatted guide promptly suggested.

The female members of my “inner crew” all burst out laughing (“Good luck with that.”)

Then my instructor-colleague encouraged me to address my current energy level.

“I now call myself ‘the 50% Barb’,” I answered, and offered a humorous rationale: “I used to rip out trees on a daily basis; now I save forests.”

My instructor-colleague chuckled (and maybe some of the students did, too.) I, in contrast, felt unsettled.

As the “persona” tasked with my recovery, “Barb 2.0” had just measured my recovery level. Evidently, only 50 per cent of my “sparkle” had returned to date, as in ten months and three weeks after I had finished my cancer treatments.

How much longer would it take to “create a tiara” or consider myself fully recovered from my recent cancer ordeal, I wondered?

“Only time will tell,” I was told by “Barb 2.0”. (At least, my health guide was smiling, which I took as a good sign.)

Eventually, we invited students for feedback and input.

“What are you hoping to achieve with this book, Dr. Reul?”

“I would love it if I could inspire you all to write something about yourselves.”

“I will definitely give it a try,” one of the students stated, much to my delight. (As it turned out, she was the caregiver to a child with special needs.)

“If nothing else,” I emphasized, “this memoir gave me purpose as a cancer survivor – and I blame your friendly instructor for making me write and publish it in the first place!”

Many “smile” icons appeared on my screen after that cheeky comment.

When it was time to say goodbye, I felt beyond grateful for having been given this opportunity to engage with a “university crowd” (for lack of a better term) as my cancer survivor self, rather than “Dr. Barb”, the professor.

“That went reasonably well,” I said to my instructor-colleague after class when we debriefed. “It did indeed,” he replied, sounding pleased.

“How do you feel about the assignment guide I drew up for the ‘Response Essay’ to go with your book that is due in late March, Barb?”

There were three steps to complete. First, students were to read Perfect Timing – “a very new book,” to quote their instructor. Then, they would have to engage with several scholarly articles about illness narratives before pondering the following questions:

- Was Dr. Reul’s memoir a “quest illness narrative”? Or did her experiences match an article that focused on academia and life writing? Or both? Or neither?

- How valid and/or reliable were illness narratives or their therapeutic use in general, and what could readers gain from engaging with them?

- Finally, how were Dr. Reul’s ideas as an author similar or different compared to other women’s perspectives on illness?

“Excellent – your students will actually have to do some thinking,” I commented with a smile.

Incidentally, a section in his assignment guide that was entitled “Notes” had made “Dr. Barb” laugh out loud.

- Do not use the grocery list thesis (more than one claim or numerous reasons for one claim).

- Do not use the teaser-trailer thesis where you say you will explore something or prove it later.

“Good luck with telling them what not to do,” I said with a big grin on my face.

“I’ll need it,” he replied, grinning back at me. “Did you want me to provide you with anonymized excerpts from the students’ response essays after the semester is over, Barb?”

“Yes, thank you, that would be awesome.”

Looking back, I had fretted quite a bit as a memoirist about letting “random people” into my head and my heart. This class visit had taught me that I had nothing to fear because it was always going to be my story, not theirs.

What I had not expected, however, was a text from my instructor-colleague a month after my class visit. It made “Dr. Barb” shake her head in disbelief.

Instructor-colleague: I have one plagiarist. So much for using brand new books [like your memoir] to prevent that from happening!”

Me: OMG! How???

Instructor-colleague: They copy-pasted some illness narratives stuff from the British Medical Journal and a conference paper abstract they found online [into their “Response Essay”].

Me: My condolences.

For the record, students who intentionally (and shamelessly!) pass off the work of others as their own continue to be a never-ending source of misery for university professors (even before the arrival of ChatGPT and “other such evil things”, to quote “Dr. Barb”.)

Personally, I will never get over the pre-pandemic student who copied and pasted 521 words of a 750-word assignment. A fake footnote citation had been included for good measure as well.

With no plagiarism detection software to turn to for assistance (yet), it had taken me several hours to locate the five websites (!) that had been used to cobble the assignment together – which was about the same time it would have taken the student to do it without enlisting “online help”, I figured.

By the way, I was struggling hard to come up with a good title for my sequel in early May when my instructor-colleague asked me about it. (“Barb 2.0” had not been in love with the various suggestions that had been floating around in my head, so I won’t include them here. Maybe I should have asked ChatGPT for help?)

In any case, I decided to go with Right on Time and excitedly told my instructor-colleague about it (“Very nice, Barb.”)

As promised, he had been in touch to share with me some impressions of having used my (first) memoir-textbook as an assigned reading in a university-level English class.

The Covid-19 backdrop had resonated very much with his students. They were also inspired by my resilience and bravery to write openly about my experience. And my sense of humour was appreciated, too.

“Wow, thank you.” I was truly humbled.

Clearly, my cancer story had made an impact on others who did not know me personally – that had been my goal all along.

How did it make me feel? Grateful beyond measure.