14. “It’s Glow Time” — 28 Days of Radiation

Listen to Chapter 14

|

Have you ever underestimated how much something would affect you because others who have been through it before you have found it to be easy?

The day after my PET scan appointment I said to my twin sister, “I cannot believe it’s Ash Wednesday today and I get to go for my first radiation therapy treatment.” If I had been a Catholic monk in the distant past, I would have spent the 40 days of Lent fasting and drinking copious amounts of beer to compensate. Instead, I continued to isolate to avoid contracting a virus that could potentially kill me and arranged my life around 28 hospital visits. Two important reminders to that end — “drink water now” and “don’t pee” — became second nature within a few days.

“How long do these treatments take?” many of my relatives and friends had asked.

“I was told 10 to 15 minutes each,” I answered.

During a recent meditation, my main guide had suggested that while receiving radiation therapy I reinforce my personal energy shields. I had first learned about how to apply these invisible — and in my experience highly effective — protective measures when taking basic training in energy healing 15 years before. They function like cocoons of light, prevent accidental drainage, and filter out any unwanted energies as well. “That will be my waiting room activity Monday through Friday for the next five and a half weeks,” I decided.

Pull down your pants

On February 17, 2021, my reminder alarm went off at 10 am, and I guzzled down half a liter of water as instructed. At 10:30 am, I put on heavy winter gear, a mask, and my favourite blue hat and took the stairs to the second floor to meet my trusted neighbour.

“How are you feeling, Barb?” she asked as we pulled out of the parking garage a few minutes later.

“I am really tired from the trip yesterday but otherwise okay,” I said truthfully. We arrived at the hospital in plenty of time; I was to text her when I was done, as she would park nearby and wait for me.

“Thank you so much for giving me a ride!” I told her and headed to the main entrance. The Covid-19 security officer upstairs reminded me that I needed to put on a fresh mask before I would be allowed to proceed. Her counterpart downstairs waved me through because I had arrived at exactly five minutes prior to my 11 am appointment. “Well done, Barb,” my guide said.

I walked up to the desk and handed the nurse the printout I had been given at my CT simulation appointment. She told me to check in with her on my way out, as she would confirm tomorrow’s appointment and give me a schedule with the tentative times for Friday, Monday, and Tuesday. Then, I went down the hall to the waiting room, grabbed a chair, and reinforced my energy shields by envisioning a protective cocoon of golden light. “Looking good, Barb,” my guide commented. He was unexpectedly chatty, and for good reason: my inner child was nervous, and his sonorous bass voice helped relax her.

Looking around the waiting room, I noticed that there were a lot of posters on the bulletin board and information about a recent, big cancer equipment fundraiser. I made a mental note to study them in detail in the coming weeks.

“Barbara?” A female introduced herself as the radiation technician who was going to look after me today. “Don’t forget to turn your chair around, so the cleaning staff knows that it needs to be disinfected,” she reminded me when I got up. I followed her and stated my full name and birthdate to verify my identity. The treatment room was just around the corner and housed a huge external radiation therapy machine.

“Put your stuff on the chair, including your hat and purse; you can keep your boots on,” she said. Then, I got onto the static exam table which was covered with a flat sheet that hid head and knee rests.

Looking straight at me, the technician said, “Pull down your pants and pretend you are a sack of potatoes.” I laughed out loud and did as I was told. Clearly, I was in the best of hands.

“My colleague and I will now adjust your position until the radiation beam lines up with your tattoos,” I was told; my hands and arms were to rest on my chest.

“Hold as still as possible while the machine is doing its thing,” the technician said. “A siren-like noise will go off to signal that the radiation beam is in use. The noise is kind of annoying, but you will get used to it.”

“No worries,” I replied. I had already wondered what the weird ding-ding sounds and lit up Beam on sign were all about while waiting for my appointment outside; now I knew.

“We are going to be on the other side of the window and can see and hear you during the treatment,” the technician announced. “If there is anything that bugs you, let us know.”

“You bet,” I replied and watched them leave the room.

Then, I closed my eyes and focused on my breathing to calm myself down. As soon as the machine started to move around the table, I began praying to distract myself. When the rather ominous-sounding, siren-like noise came on, I kept reinforcing the energy shield around my body, specifically around my fully exposed pelvic region. Soon after, the technician came back in. “That went by fast,” I remember thinking.

“Good job, Barb; you are all done for today,” she announced. “Remember to put unscented lotion on your belly at least once a day.”

“Consider it done,” I replied. I got dressed and filled out a patient survey upon her request. “I will see you tomorrow,” I said and headed back to the reception desk to retrieve my updated schedule.

“It was not too scary,” I said to my trusted neighbour, who pulled up at the front entrance of the hospital a few minutes later. I texted the new appointment times to her from the backseat. “Let’s hope there won’t be too many last-minute changes,” I said, after pressing the send button. She told me not to worry and suggested I take it easy.

And I did, still exhausted both physically and emotionally from travelling the day before. In fact, I rested until it was time to get up and attend the first of six online Lenten Bible Studies, led by my wonderfully bubbly pastor, a fellow extrovert whose insightful sermons I looked forward to every Sunday. Under normal circumstances, I would not have been able to participate in evening activities because the six weeks before Easter were often the busiest of the semester. But this year I could and would get involved. The topic to be explored in 2021 was “hope,” which I took as an additional sign from the universe to sign up. Specifically, we were going to “sense”, “smell”, “hear”, and “taste” hope through prayer and discussion.

“That was really fun,” I said to my pastor during the chat time afterwards. I apologized for not participating in the discussion, as my energy was still low.

“No talking is required,” she replied perceptively.

“It will be wonderful to be a part of meaningful conversations in the next five weeks that will not focus on my current health challenges,” I told her before I said goodbye and turned off the computer.

Have you ever been shot?

“Oh no — we have to go back to the hospital,” I said to my trusted neighbour the next day on our way home after my second radiation treatment. Much to my embarrassment, I had forgotten to pick up my updated appointment schedule on my way out. She smiled, turned around, and dropped me off at the main entrance. Five minutes later I apologized to the nurse at the reception.

“I am glad you came back, Barb — the radiology nurse wants to see you.”

“Now? What about?”

“I don’t know, but please go to treatment room 1 and wait for her.”

I texted my trusted neighbour about the change in plans. “I’ll wait for you, no worries,” she replied. “I hope it won’t take too long,” I said.

Five minutes later, I smiled when the nurse who had shown me the vaginal stretcher devices in mid-December came in.

“Hello Barb — we have got your PET scan results,” she informed me.

“Is it bad?” I asked, suddenly worried.

“Not at all,” she replied. “But the radiologist has ordered a couple more tests.”

A short while later, the radiologist himself arrived. “The good news is that there is no cancer anywhere,” he told me.

“That’s great,” I said and let out a big sigh of relief. I could feel my inner child jumping up and down for joy, yelling “we are going to be fine – we are going to be fine – we are going to be fine…!” My main guide nodded in agreement. “Told you so, my dear.”

“I want an MRI scan to investigate that cyst further,” the radiologist continued.

“Is that really necessary?” I wondered, feeling all “scanned out” after the PET scan adventure two days ago. Thankfully, the MRI did not require travel. It would be done at the other hospital in town sometime before mid-March.

That was not all, however.

“You also have the beginning stages of a tonsillitis,” the radiologist informed me. Was my throat sore?

“No,” I said, somewhat in shock. Did it hurt when I swallowed? “No,” I replied.

“An ear-nose-throat oncology surgeon will see you next week, either right before or after a scheduled radiation treatment,” the radiologist announced.

“Wow — he’s serious,” I thought and mentally updated my list of procedures.

“My nurse will now walk you through an MRI safety questionnaire.” He wished me a good day and left.

The next ten minutes were spent on learning about what could be harmful to or interfere with the Magnetic Resonance Imaging scan I would soon be able to add to my growing list of medical procedures. It made me wonder how many my father had undergone while being treated for cancer in the 1970s. Could my dislike of hospitals — I could never be a physician or nurse — might somehow (or directly?) be related to being dragged along on what I perceived to be boring visits? Some had involved lengthy train rides as my mom did not have a driver’s licence.

The oncology nurse’s questions brought me back into the present and ranged from predictable to bizarre.

Had I ever had an MRI before?

“No.”

Did I have a pacemaker, an IV access port, or any surgical hardware such as pins, rods, screws, plates, or wires?

“No,” I answered and confirmed that I did not have any artificial joints or limbs either.

“Have you ever had an eye injury from a metal object, like shavings or slivers?” she asked. When she saw the puzzled look on my face, the nurse explained that it was quite common amongst certain trade workers.

“No.”

“What about medication patches, breast tissue expanders, and permanent makeup?” she wondered.

“No,” I replied — and laughed out loud when she wanted to know whether I had ever been injured by a bullet. “I am sure I would have remembered that,” I quipped.

“Any history of kidney or liver disease, diabetes, claustrophobia, drug or latex allergy, or dyes related to other scans?” Once again, I answered in the negative.

“Excellent, Barb,” the nurse said and told me I was free to go.

“That was truly weird,” I said to my trusted neighbour on our way home. Before she could offer a response, my little one piped up. “No,” she said. “That was so much fun!”

Let’s not jump the gun

On the following Monday, my GP wanted to chat with me about the PET scan results. I was happy he did, as I feared I had missed or misunderstood something the radiologist had addressed. After he had walked me through the report, I complained about the MRI scan the radiologist had ordered. My GP sided with his colleague: “I like his approach — very thorough.”

“Any more questions, Barb?” my GP asked.

“Two, in fact,” I responded. “Do you have a sense of when I will be vaccinated against Covid-19?” I was tired of isolating at home and missed my friends terribly.

“Not yet,” my GP answered, but assured me that my turn would come.

Then, I asked him about returning to work. I had successfully applied last year for a research sabbatical from July to December 2021. What if I were not healthy enough by then to make the most of it? My GP immediately wondered whether I could ask for it to be moved to 2022. He was pleased to hear that my academic dean had already suggested I include that scenario in my application letter.

I was also keen to return to work sometime during the second half of 2021; if nothing else, my mental health would benefit from it. “We will talk about it after the radiation treatments are over,” my GP said. He also agreed to deal with my employer and insurance on behalf of my oncologist who would soon go on leave.

“You are awesome — thank you,” I said, grateful as ever for his continued support.

Ten minutes later, the phone rang again. “How are you, Barb?” my oncologist asked.

“Fine, but weren’t you supposed to call me the day after tomorrow?” I replied, frantically checking my calendar. The little girl inside me promptly got anxious and wanted me to hang up. Since my main guide wanted me to stay on the line, he handed her his fancy top hat to play with.

“That is correct — do you have time for me now?” the oncologist asked.

“Yes, of course,” I said and told her about several post-chemotherapy side effects that continued to ail me.

“The fatigue will continue while you are receiving radiation and for some time afterwards,” she told me. I should not get hyped up about the continuing numbness in my left foot and right thumb. “Just give it time,” the oncologist advised. She also commended me on having attended a cancer survivor support group meeting a month before.

This, in turn, reminded me to ask her what would happen after I finished treatments. “My colleague will perform a pelvic exam in late May — you will get a letter in the mail about it,” was her answer. Then she told me that she would be back at work on October 1.

“That’s fantastic news,” I exclaimed. “One last thing: my GP has suggested I move my six-month sabbatical to next year,” I said. “How do you feel about that?”

“It’s a good idea,” she said. “We have pushed you very hard ever since your surgery last August,” she admitted and insisted I take some time off: “Your body will thank you for it in the long run.”

I promised that I would delay my return to work, wished her all the best (she was going to be a wonderful mom!), and hung up.

Kopfkino

A mental image of me sitting on my favourite beach 2000 km to the west and watching the sunset surrounded by my relatives then appeared in my mind’s eye. If this had been 2019 instead of 2021, I would have booked a flight in late April and stayed with each of my sisters, who live in two of the most beautiful regions of Vancouver Island.

“I miss spending time with you as well as the beaches, forests, and mountain views,” I would tell them, then engage in a fair amount of Kopfkino (literally “head cinema”) to compensate. What else was I supposed to do, given that all travel of the non-essential kind was on hold due to the pandemic?

My oncologist’s request to go easy on myself in the coming months was not lost on others. “Does your medical insurance in Canada cover a three-week stay at an approved medical facility after you are done with treatments?” my older sister had asked early on. This was standard procedure in Germany, and I had seen the difference it had made to her own recovery from two back surgeries and a stroke; a mutual German friend had even met her future partner while recuperating away from home after chemotherapy.

“I wish it were an option here, too,” I answered. “But it could be so much worse.” To date, I had spent only $100 out of pocket at my pharmacy down the street. If I had received my cancer diagnosis in the United States, I would likely have had to take out a loan to finance my way back to health, according to my friends down south. Thank you, Tommy Douglas, premier of Saskatchewan in the 1950s (and maternal grandfather to actor Kiefer Sutherland), for introducing universal healthcare in Canada. I feel so lucky and privileged to have called this country home for nearly 35 years.

A special task

“I wish these hot flashes would stop,” I declared at 2:30 am the next morning, February 23, 2021. After drinking some cold water and doing a bit of light reading while my body temperature returned to normal, I went back to bed and tried to fall back asleep.

“Get back up and turn your computer on right now,” said my main guide, a serious tone in his voice.

“Leave me alone,” I mumbled and adjusted my ear plugs.

Ten minutes later, I gave in to his request, got up, fetched my computer, and turned it on, somewhat begrudgingly.

“All right, what exactly do you want me to do?”

“Write down your cancer story, Barb.” All of a sudden, I felt wide awake.

“You want me to do what?”

“Write down your cancer story, Barb,” he repeated, knowing full well that I had heard and understood him perfectly the first time.

And before I could begin to ask “Why? Why me? Why now?” he started dictating a preliminary book title — “Patience required” — and 15 chapter titles to me. Forty-five minutes later I stared, somewhat incredulously, at a Table of Contents that was virtually complete. I was no stranger to what is known as automatic or channeled writing. In fact, I benefitted from it as a university professor, especially when I carried out research and prepared scholarly publications. However, in this case, the time of the day (or night), speed, and content clarity had been second-to-none as far as I was concerned.

“The universe has special plans for you, Barb,” my guide announced — I was to share my recollections with the explicit goal of raising funds for cancer research.

I was astonished, to say the least. “You want me to write a non-academic book?”

The idea was not new. For years I had cracked jokes about writing my memoirs, tentatively titled The Accidental Academic. When I found out that the title was already taken, and my oldest sister announced she would publish an autobiography, I dismissed the notion. “So much for making millions and retiring early!” I had jokingly concluded at the time.

What scared me now was not the act of writing itself; writing was second nature to me, a seasoned academic. I was also accustomed to seeing my name in print ever since I had entered graduate school.

So, what was the problem?

The idea that I would grant people I had never met access to my innermost thoughts — instead of directing them to intriguing archival documents and scholarly publications that examine them — made me feel decidedly uncomfortable. I had always been careful about protecting my privacy and that of my loved ones: this was the main reason I posted very little on social media platforms (and why there are no names of people given in this book, in case you had been wondering).

My main guide was quick to remind me that I would, of course, have complete creative control and could share as much or as little as I wanted. But did the world really need another, albeit inspiring, cancer survivor story?

“What do you usually say to your students when they are hesitant to give something new a try which you know will help them reach new heights?” my guide asked.

“Um — do it, or Dr. Reul will find you…?”

“No, the other one.”

“That they might just enjoy it.”

Suddenly, I felt all my fears of “going public” melt away.

It also began to dawn on me why the fundraising campaign story boards on the walls of the radiation therapy waiting room had touched me so deeply. Several community leaders — including a local financial institution as well as a rock band that involved the town mayor and a fellow academic — had raised a whopping 1.5 million Canadian dollars in 2019/20 to replace an aging CT scan simulator machine. Thanks to their impressive efforts, my medical team had been able to plan my radiation therapy treatments with much greater precision.

“I get it,” I thought. “The universe wants me to give back, right?” My guide smiled, took off his top hat, and bowed to me. “I will do my very best,” I vowed, turning off the computer and going back to bed.

When I woke up several hours later, I checked to make sure I had not just imagined the whole thing. It was all still there — so, why was it so hard to write the introduction?

“Don’t overdo it, Barb; you still need a lot of downtime,” my trusted neighbour, relatives, and close friends reminded me when I told them about my intentions.

“I know, but my journey of recovery has now taken on an entirely different meaning, if not a higher purpose,” I declared confidently.

My best friend also reminded me that it would be very therapeutic to tell my story my way. This, in turn, jogged my memory about something I had learned early on in my academic career: it is what you do after you have finished a project that counts the most.

My brother-in-law, a published author himself (and poet laureate of the Comox Valley in 2020/21), promptly offered to help with proofreading and editing my manuscript. So did a dear colleague who felt that my recollections and reflections would make a welcome and valuable addition to his English literature class that examines narratives of illness.

When I began writing my story down in earnest, however, I realized that I had no idea when my manuscript would be finished — my energy continued to be very low — and how long it might be (“keep it short and sweet”). What had become increasingly clear to me, however, was that I had been given an unexpected gift at an unexpected, but perfect, time.

Open wide

Two days later I checked in at the cancer clinic upstairs for my appointment at 2:10 pm with the ear-nose-throat doctor. Watching the clock like a hawk, I became increasingly anxious when everyone else’s name was called but mine. I had told the receptionist that the radiation therapy technologists were expecting me at 3:05 pm for an appointment at 3:10 pm.

“Oh well,” I thought. “They are probably just running late.” My inner child was not impressed, however. She promptly voiced her anger about me forgetting to bring a chocolate bar for her (“just in case”).

At 2:55 pm, I got up and talked to the receptionist: “Should I go downstairs for my treatment and come back afterwards? Or ask for either one to be rescheduled?”

“I cannot find you in the computer,” she declared, slightly frustrated. Her colleague who had taken down my name had left for the day and could not verify my story.

As if by magic, my favourite radiology cancer nurse appeared. “What are you still doing here, girl?” she asked, making me laugh. “Get yourself down there; I’ll handle things up here.”

“Bless you,” I said and ran off.

When I rushed back up there 20 minutes later, another nurse apologized profusely for making me wait.

“It’s fine,” I said. Shortly after, the ENT oncologist wanted me to know how very sorry he was for the long delay.

“It happens,” I said. Hopefully, the resident and medical student he had brought with him were paying close attention to his excellent bedside manner.

“The examination will only take five minutes,” he said. Then the nurse apologized to me on behalf of the radiologist who was running late.

“No worries,” I replied. With a bit of luck, it would not take him as long as it had in mid-December to join us, I figured. He appeared a few minutes later, albeit virtually, on an iPad that had been positioned on the windowsill across from my treatment chair so he could watch everything. “Don’t forget to check her tonsils,” said the radiologist to the ENT doctor, who tried his best to ignore him.

“You are not going to like some of the things I will do now,” I was told.

“It’s fine.” I replied. I was not going to make a fuss: after all, I had survived six rounds of chemotherapy. To the radiologist’s surprise and everyone else’s relief, including my own, everything looked normal.

“It’s always best to check right away, just in case symptoms return three months from now,” the ENT doctor added, with the radiologist nodding in agreement.

“Thank you,” I said and watched everyone leave the room except for the nurse. “Where is the closest washroom?” I asked her. My full bladder had been killing me for the past two hours!

Mount Vesuvius

Exactly 14 days after my first radiation therapy, the side effects I had been warned about began.

“Take your diarrhea medication only if you have more than three watery stools per day,” a radiation therapy nurse had instructed me during the weekly assessment.

“I will,” I promised.

“Have you stocked up on low fibre foods?”

“Yes, my fridge and freezer are full.”

Even though cooking had become a favourite activity of mine during the pandemic, it was hard to get excited about preparing what I considered boring meals. It felt odd to buy white rice that would cook in mere minutes (“I don’t think I have had any in decades,” I remember telling my trusted neighbour) and use high-protein bone broth powder which my pastor friend’s daughter who works for a dietary supplement company had sent in the mail.

“Any fatigue yet?” the nurse asked.

“You mean still?” I quipped. “Exercising daily with my favourite online personal trainer has kept it at bay.”

“That’s wonderful, Barb,” the nurse replied.

Then I proceeded to tell the nurse that, to my delight, my twin sister had decided to take additional training to assist individuals on the cancer continuum with regaining their physical strength.

“I want to be an agent of change,” my twin had told me on the weekend.

“Just like me,” I replied, referring to my book project. “Let me pay for the course,” I offered. “It is but a small token of my continued appreciation for how much of a difference your expertise as a fitness professional has made in my life.” She agreed — and then put me through my paces.

The next morning, I asked myself what I was going to eat that would not upset my bowels. Berries, nuts, and lettuce, and anything that would give me gas, such as beans, Brussels sprouts (my favourite), and coleslaw, were taboo.

“Those three yogurt containers full of home-made chili will have to wait until later,” the dietician had said when she called me to find out how I was doing.

I was to peel my potatoes and apples, and swap everything that contained wheat for something that did not. “There goes my spelt and wild rice bread,” I thought, with much regret. I had been completely unaware of the high amount of fibre I had added to my diet during my weight loss journey several years before.

“It’s all temporary, Barb,” the dietician reminded me. She wanted to know how much quality time I spent on the toilet these days.

“I am fine in the mornings,” I told her.

“That’s because you have fasted at night,” she noted.

“It gets worse after lunch and is terrible in the evening and at night,” I reported. “And I had a really close call yesterday.”

The weather had been gorgeous, which compelled me to accept an invitation to join the couple who had helped me with setting up my TV for a physically distanced walk.

After fifteen minutes of enjoying each other’s company, I suddenly leaned on my walking poles and bent over. “What’s going on, Barb?” they asked. Sudden belly cramps made me gasp for air.

“I need to go home — now!” I announced.

In hindsight, I should probably not have joked to them earlier on about my restricted diet (“I feel like a bunny”) and frequent visits to the washroom (“I bought 60 rolls of toilet paper on sale the other day”). Walking as fast as I could, I was terrified I would soil my jeans on my way home. My friends, in turn, were scared that I would faint from the pain.

After what seemed like an eternity, I finally stood in front of the building elevator, waiting for the door to open. I concluded that I should never have moved to the seventh floor, while pressing my butt cheeks together as much as I could on the way up. After entering my apartment and pushing the door shut, I pulled down my pants and sat down on the toilet with literally two seconds to spare. “Let the volcano erupt,” I winced and closed my eyes.

“Barb,” said the dietician, “from now on, take one pill a day whether you need it or not, okay?” This was not a normal case of diarrhea, she argued, but caused by the radiation.

“No joke,” I thought.

I checked with the nurses at the hospital, who agreed with her instructions. A dear friend who suffered from irritable bowel syndrome also drew my attention to the quick-dissolve variety of the over-the-counter diarrhea medication I was using. “Put a couple of pills in every purse you own,” she advised.

“Good idea.”

I put some on my nightstand and inside jacket pockets as well. “Better safe than sorry,” I concluded, praying daily that my bowels would soon begin to quiet down.

The right fit

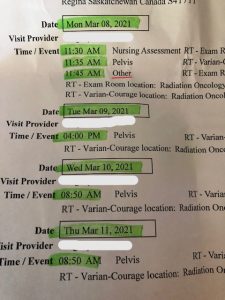

“If you are free, could you come in right now instead of in an hour?” my favourite radiology nurse asked on the phone the next morning. It was March 8, 2021, the day of my vaginal sizing appointment (labelled “Other” on the radiation itinerary). I had not been looking forward to it even though I was told it would feel like a pelvic exam and should not hurt.

“This is not going to work for me, folks,” I said when the sterile, decidedly unsexy stretching device chosen by the radiologist caused definite discomfort. He motioned the nurse to hand him a different one.

“Better?” he asked. I nodded.

After the radiologist left the room, the nurse handed me a dilator made from heavy plastic and a tube of lubrication jelly, wrapped in a brown paper bag for privacy. I am glad she could not read my mind when I put it in my purse — my inner stand-up comedian was having a field day.

Did the device come in other colours than stark white, and was there a luxury version available that vibrated? Were there other adult gadgets kept under lock and key somewhere in this hospital that warranted close inspection? Looking down at my tent-like hospital gown, I could guess the answers.

“Some ladies like to insert the vaginal stretcher prior to intercourse,” the nurse said, looking me straight in the eye.

“Good for them,” was my sassy reply.

When I got home and read the instruction sheet, I was no longer amused. The thought of getting to know a piece of hard plastic intimately over the course of the next year did not excite me at all. There was also no way I was going to “close my eyes and think of England” several times a week, as had been suggested by a certain “Dr. Google.” The odds of my favourite movie star offering to warm my sheets anytime soon were also slim to none. Would my bedroom soon qualify as a monastic outpost?

If nothing else, my huge belly scar was healing nicely, the radiation therapists and nurses had assured me. When I mentioned it to friends in Australia and New Zealand who had both had hysterectomies as well, they jokingly suggested a “I’ll show you mine, if you show me yours” Zoom party. I cringed, wondering when I was going to be comfortable with my post-surgery abdominal “look”, if ever. I was not interested in hiding my scar with fancy lingerie or in covering it up permanently with a tattoo (as suggested by my trusted massage therapist).

The scar was also surrounded by muscles that seized up if I did (too many) twists, crunches, or planks. In other words, I could kiss a flat stomach goodbye forever. “Give it time,” my twin sister advised. “If you work with your body, it will surprise you.” I decided to give her the benefit of the doubt.

It was snowing hard the next morning when I left to walk to the other hospital in town at which my cancer journey had begun seven months earlier. As instructed, I checked in at 11:45 am for my MRI scan at 12:30 pm, not having had anything to eat or drink since 8:30 am. Then I waited for almost two hours, spending most of it in a freezing change room clad in a flimsy hospital gown and robe. Leaving on my hat, winter jacket, wool socks, and heavy boots helped, as did a warm blanket offered by a kind nurse who apologized for the delay. However, by the time I was taken to the MRI treatment room, I was a frozen pretzel.

“I’ve got a radiation therapy appointment at the other hospital at 3:30 pm and need to drink 500 ml one hour beforehand,” I informed the nurse when I got onto the moveable bed that was attached to a giant tube.

“I’ll have it ready for you when you are finished,” she promised, adding, “It’s going to be loud in there.” The ear plugs she had handed me next promptly fell out, only for another nurse to grab a set of over-ear headphones and put them on me while I was being pushed into the tube. Having reinforced my personal energy shields, I closed my eyes and then alternated Christian prayers in German and in English with repeating my favourite Sanskrit meditation sounds and phrases to distract myself.

“You are all done, Barb,” the nurse said 45 minutes later. “I called the radiation therapy department at the other hospital and told them that you might be a couple of minutes late today. I did not want you to have to rush there,” she explained.

“Thank you,” I said and got dressed, relieved for it to be over. Then I gulped down a large paper cup filled with ice cold water on my way out, walked home as fast as I could through the snow, ate a quick, intentionally bland lunch, and made it to my next appointment on time.

Please cheer me up

On the following day, a Wednesday, I could not figure out what was wrong with me. I had very little energy and wept before and during the car ride to the hospital. My trusted neighbour managed to calm me (and my inner child) down, but I was still emotional when I walked into the hospital.

“I’ve had an awful morning,” I said to the radiation therapists.

“Didn’t you tell us you were a music professor?” one of them said.

“You’ve got a great memory.” I positioned myself on the table. A few seconds later, rock music blasted through the speakers. “Oh no,” I moaned.

“Are you more of a country girl?” the technician wondered.

“No, I like classical music.”

“I will see what I can find,” she said — and then the cheerful first movement of Mozart’s Eine kleine Nachtmusik began playing. My mood immediately improved, and when the opening of Vivaldi’s Spring conjured up birds and blue skies in my mind, I was positively beaming.

“Thank you so much for the music therapy,” I said after the treatment. It was going to be an awesome day after all!

I was wrong.

Bad fatigue hit shortly after I returned home. I cancelled my daily exercise session online as a result, the first time since I had finished chemotherapy. “I hate feeling so weak,” I said to my twin sister. Fluctuating body temperature issues and persistent ear noises as well as a numb left foot and right thumb did little to improve my mood the next day. “I am so sorry to hear that, but at least the colour of your face no longer matches that of your bedroom walls,” my twin sister commented.

Neither of us expected me to “travel back to chemo land” — that is, experience crippling fatigue — again on the following Saturday.

I spent most of it in bed, exhausted, weepy, and feeling sick to my stomach. My trusted neighbour, an excellent cook, brought me supper, which she had carefully prepared according to the list of foods allowed. It tasted great, but a short while later an awful diarrhea attack and painful cramps made me curse in German. How much longer would these side effects continue? I, for one, was ready to quit treatments (“I am cancer-free, remember?”), but my main guide would not hear of it.

“I am most concerned about your nausea,” another radiation therapy nurse said to me on the following Monday during my weekly assessment.

“I did not have any while undergoing chemo,” I told her, hoping for answers.

“I am not sure what’s going on,” she admitted. “After all, your stomach is not being radiated, only your pelvis. Are you watching your diet carefully?”

“Yes, like a hawk, but I’m not really hungry these days.”

“You have to eat, Barb!” the nurse reminded me. “Take the nausea pills left over from your last round of chemotherapy.”

“You bet,” I replied, congratulating myself on not throwing them out or, worse, losing them during my move in early February. I had been absolutely mortified when a big folder with important documents had disappeared. I had been so careful (or so I thought).

“Do you have any idea how much I have fretted over this?”, I asked my clergy friend, frustrated to the core.

“It happens,” she said.

“Not to me,” I replied. “Dr. Barb” was nodding vigorously.

“Surely, you would have made virtual copies of these files?”

“Yes, as a matter of fact.”

My clergy friend laughed out loud. “So, what has the universe been trying to teach you?”

“Um — that being human means we mess up occasionally?”

“You got it, Barb.”

In hindsight, I realized that the missing documents were all related to my long-term retirement plans. They also represented my distant future — no wonder I had been so distressed.

When my GP called the next day, he had excellent news for me. “You will receive a letter from the provincial health authority in the mail shortly that allows you to jump the vaccination cue,” he said. I promised to make a vaccine appointment as soon as it arrived or call him if it did not arrive within three days.

“Since I’ve got you on the phone — nobody has talked to me about the MRI scan,” I said to him. “Would you mind taking a look?”

“A report has not been submitted yet,” he said after checking online.

Then he became very serious. “Barb, given that the Covid-19 numbers have skyrocketed in town and will likely continue to climb, I want you to walk by yourself and not enter a supermarket for the next two to three weeks.” I was not surprised, and neither were my trusted neighbour and the couple who had helped me with setting up my TV — they immediately offered their assistance with getting groceries.

“Just tell us what you need, and we will get it for you,” they said, much to my delight and relief.

That evening I threw up.

“That’s not good,” said my GP when he called the next morning. “Keep taking the medication,” he advised.

“What about the MRI scan?”

“There is nothing new to see.”

“Not even the bladder cyst?”

“It is now described as a cystic area at the front of your pelvis,” he clarified and told me not to worry about it.

“Fair enough,” I said. Then, I thanked him for getting back to me so quickly and hung up. Fifteen minutes later, I had convinced myself that my medical team had probably overlooked something after all. My main guide promptly threatened to slap me with his top hat. This, in turn, amused my little girl and even made “Dr. Barb” laugh. Yup, never a dull moment in my head!

Glowing on the inside

A couple of hours later, I went through the two Covid-19 screening points at the hospital. Both security officers recognized me by now, even with a mask on. The female liked my blue hat: “It really suits you,” she said more than once. The male appreciated my punctuality: “Go right ahead,” he said every day.

Neither of them was aware that on that day, March 18, 2021, was my third and last internal — that is, vaginal — radiation appointment. It involved a different set of nurses, who wondered whether the two previous treatments had caused any side effects. Still reeling from my recent vomiting episode, I entertained them with a hilarious “maybe I am allergic to meatballs?” routine. Then I changed into a hospital gown and robe to hide the fact that I was naked from the waist down, walked across the hall, and used the washroom to empty my bladder.

“You know the drill by now, Barb,” one of the nurses said. I got on the table, opened my legs, and took a deep breath when a vaginal stretcher, identical in size and shape to the one I had been given, was inserted. Unlike mine, it was attached to a radiation monitor via a long cord.

“Pardon me, is that a Geiger counter you are using?” I asked the medical radiation physicist on duty who had joined the nurses that day.

“Yes,” she said, explaining that it detects the presence of radiation inside my body. “It’s on,” she declared, and then everyone left the room for four minutes.

I was trying to get through my usual prayer routine but was distracted by horrible rock music that someone had forgotten to turn off. “Oh well,” I thought. Was that my pelvis glowing on the inside?

“Here’s some lube for you,” I was told when I hopped off the table. When the three nurses detailed the vaginal stretching routine that I was to adopt for the next year, I felt like a student in class whose professor was worried that they would forget or, worse, refuse to follow explicit instructions. It was critical to start exactly one week after I had finished treatments, the nurses emphasized.

“That’s on Good Friday, ladies,” I said. “But I am not sure how good of a Friday it will be,” I quipped, making them chuckle.

“You can always substitute intercourse,” one of the nurses suggested.

“Your wish is my command,” I deadpanned, likely making the physicist wonder what the loud laughter around the corner was all about.

“By the way, I only have six external treatments left. What happens after that?” I asked.

“For at least two weeks afterwards, be prepared for the side effects to get a whole lot worse.” The nurses smiled when I let out a frustrated moan and rolled my eyes.

“Will the radiologist want to see me again?” I wondered.

“The computer says you have an appointment on May 26. Watch out for a letter in the mail,” one of the nurses said.

“I will.” I thanked them and went across the hall to change back into my regular clothes.

The end is in sight

“I have two questions for you,” I said to my trusted neighbour during the drive home. “Can you think of something I could give you as a thank you for all your support lately, especially for chauffeuring me back and forth to the hospital five times a week?”

“I’ll let you know,” she answered. Having her choose her own presents had worked well at Christmas time. She had also appreciated the small gifts and self-made cards I had brought with me to the car or dropped off at her place to express my continued gratitude. Ultimately, she chose a beautiful picture of a vase with poppies by an artist she admired.

“You have excellent taste,” I said.

“I know,” she replied, and we both smiled.

I had also decided that I would drive myself to the hospital from now on. There were only six appointments left, and my neighbour’s first Covid-19 vaccination was scheduled the week after I finished treatments. My daily hospital visits posed an additional, avoidable risk, I argued. She immediately agreed, visibly relieved.

“Let’s hope all of the appointments will be in the morning, when I have the most energy,” I said to her. Nearly half had been changed at short notice, some of them to the opposite time of day.

“If you are not feeling up to taking your car, I will drive you,” my trusted neighbour decided.

“Thank you,” I said, praying for good weather as well.

The promised vaccination letter was waiting for me when I got home.

The local drive-through, for which many of my older friends had lined up as soon as they were eligible, was not an option for patients in the critically vulnerable category like me and my best friend, who had received her letter as well. Twenty minutes later, I received a call-back, and five minutes later I entered “vaccination on April 8, 2:40 pm, University” into my calendars. “What a relief,” I thought; our city had been a Canadian hotspot for weeks. Receiving my first shot almost two weeks after having finished radiation therapy would also give my immune system time to recuperate.

“Do you have a date for your second dose yet?” my German friends and relatives wondered when I told them about my upcoming vaccination.

“No, but it will happen this year sometime before August 8,” I responded. The Canadian government had implemented a much longer waiting period between vaccinations than European countries.

“I wish it would stop snowing,” I said, while driving myself to the hospital during the last week of treatments. On Monday, I ended up spending an extra ten minutes in the car because I had left too early but did not want to wait in the hospital, for obvious reasons. On Tuesday, I started crying in the car because I was missing the pre- and post-appointment chats with my trusted neighbour, who still texted twice a day to make sure I was doing okay. On Wednesday, I compensated for feeling lonely at home by carefully sucking the chocolate off a pound of almonds before throwing them into the trash.

My bowels were not amused and reminded me repeatedly that, besides chicken, fish, and turkey, my safest food choices were bananas, canned peaches, oatmeal, white rice, butternut squash — and boiled carrots. “Will I turn into the Easter bunny soon?” I wondered on my drive home from the hospital on Thursday.

To my great surprise, my trusted neighbour showed up at my door that evening. She handed me not only homemade pumpkin muffins but also a lovely “Congrats! You’re done” card. When I read that she had been happy to support me on my journey to even better days, I promptly burst into tears of gratitude. Then, I admitted how much I missed talking to her every day. “Why didn’t you say something, girl?” she asked and immediately agreed to drive me to the hospital the following morning.

One last time

“Hi there,” I said to the nurse at the reception desk on Friday, March 26, 2021. “I have a thank you card for you and your colleagues, as today is my last treatment — would you please pass it around?”

“How kind of you,” she replied and put it on her desk.

Then I waited to be picked up by the radiation therapist down the hall. I handed her the other card I had prepared before taking my jacket off. Her astonishment made me suspect that she and her colleagues had not expected to be thanked for what they did every day. Earlier that week I had asked one of her colleagues about the type of training that was required. To my surprise, I found out that they were not nurses, but a similarly close-knit professional community.

“We are ready for you, Barb,” the other radiation therapist said. I got on the table and pulled down my underwear and faux fur lined leggings. “These are really cool pants,” I was told.

“Thank you; they are my favourites.” I watched the therapists leave the room. Then I psyched myself up for what was to come, one last time.

Unlike during the previous 24 external radiation therapy treatments, I had decided to leave my eyes open today and watch the machine move around the table. It turned out to be unexpectedly boring — until every single guide and angel who had been with me through six rounds of chemotherapy literally lined up at the end of the table for a photo opportunity of sorts. When my main guide took off his top hat in reverence and motioned for my late parents and several other close friends who had passed away to join them, including my friend from Montreal holding her clarinet, I began to sob. “Smile and wave goodbye to Barb, everybody,” he said when the noisy Beam on siren went on.

“Thank you for everything,” I thought, and then crossed the finish line of my cancer treatment journey, albeit only in my head.

Wiping the tears off my face, I put my clothes and hat back on.

“Here’s a letter to confirm that you have finished treatments,” said the radiation therapist. “Continue everything you are doing for two weeks and call your radiologist or the social worker if you need help.”

I put the piece of paper in my purse and said an emotional goodbye.

On my way out, another therapist stopped me. “I loved your card,” she said, “especially the part about wanting to tell your story and raise funds for cancer research.”

Her heartfelt words promptly made me cry again. Having lost a child, she had written a book herself and found it to be very healing. Could she tell how frustrated I was that Covid-19 restrictions prevented me from giving her and all the other hospital staff thank-you hugs to express my gratitude for welcoming me into their family for the past five and a half weeks? I hope so.

Help me celebrate today

“Will you do something special to mark this occasion, Barb?” my trusted neighbour asked me on our way home.

“She is right — you should put something on Facebook,” my main guide whispered into my ear an hour later during my meditative walk at a nearby park.

“You want me to go public already?” I thought.

“It’s time,” he said, smiling.

Before turning on the computer, I called my twin sister and told her about my plans. “Is there anyone among your Facebook friends who would scold me for not telling them what’s been going on with you?” she asked.

“I don’t think so,” I replied. I had not considered that scenario but understood her worries perfectly, given how fervently I had insisted on keeping my health journey private. “If that should indeed happen, let me apologize to you on their behalf right now,” I said.

At 1:07 pm, I posted the following message:

“Barbara Reul is feeling thankful on 26.03.2021: Help me celebrate today — I finished a 9-months-long cancer journey that included a sudden diagnosis in late July, followed by major surgery, six bumpy rounds of chemo, and 28 taxing radiation treatments. Thank you to everyone who I invited to help me navigate uncharted waters. I will pay forward all your acts of kindness by writing down my story and then share it widely to help raise funds for cancer research!”

To my genuine surprise, close to 150 friends clicked on the “like”, “love”, and “care” emojis within 48 hours. “I had no idea there were that many because I am super careful with accepting requests and hardly post anything,” I said to my clergy friend in Alberta, who was thrilled about my post.

Over 90 people had taken the time to offer wonderfully uplifting, heartfelt comments. One of my favourites had been penned by Winston’s mom, one of my walking-buddy colleagues: “What a road it has been, and you’ve tackled each and every step with grace, poise, dignity, strength and of course — one hell of a sense of humour!” I laughed out loud when a couple of days after the post she also called me “Barbara Reul 2.0.” Later that evening, I rejoiced with my Greek friend and colleague, who was celebrating her five-year anniversary of having been cancer-free. There was hope for me!

Not everyone was impressed with my post, however. Several people shared their disappointment about having to find out through social media what had been going on, while others judged me openly for not allowing them to be more involved in my health journey. “Not classy,” I thought. It took me weeks to admit that my own, unfair reaction at the time deserved that label and months to view their comments for what they were, namely expressions of genuine concern for me. If only they had used e-mail to contact me, like a former professor and his wife did, as well as two German fellow scholars who identified themselves as fellow cancer survivors as well. “Very classy,” I concluded.

To my great relief, very few individuals asked for details. “Do you feel comfortable telling me what kind of cancer it was?” the daughter of my late mother’s best friend asked gently via Facebook Messenger. As a trained nurse who had spent her early years on the oncology ward, she knew exactly how to ask me to disclose information without violating my privacy.

Much to my surprise, a beautiful bouquet of flowers arrived shortly after I had pressed the post button on Facebook. I could not wait to open the card that accompanied it. “Happy last radiation treatment day! In awe of your bravery, resilience, and toughness,” it read and was signed by our wonderful library coordinator at work. I was crying when I texted her back to thank her from the bottom of my heart. Life was good!