15 Interpersonal Violence in Northern Saskatchewan Communities: A Case Study

Darlene M. Juschka; Mary Rucklos-Hampton; Melissa Wuerch; and Tracy Knutson

Darlene Juschka, Mary Hampton, Melissa Wuerch, Carrie Bourassa, and Tracy Knutson

Introduction

In the following case study my effort is to argue for a harm reduction approach to interpersonal violence in northern Saskatchewan. Using a feminist critical theory approach, I engage individual interviews of interpersonal violence service providers collected over a two-year period (2012 to 2014). Telephone interviews of Saskatchewan service providers, ranging from health care, shelter, and victim service workers, and RCMP, were conducted. The data was collected as part of a larger four regional (AB, SK, MB, NWT) SSHRC-CURA funded grant ($1,000,000) titled “Rural and Northern Community Response to Intimate Partner Violence” conducted over five years (2011 to 2016) and headed by Dr. Mary Hampton (Luther College, University of Regina) and Diane Delaney and then JoAnne Dusel (past and current directors of the Provincial Association of Transition Houses and Services of Saskatchewan). The project operated under the auspices of RESOLVE Saskatchewan, a network of researchers, community experts, and organizations that focus their efforts on interpersonal[1] violence across the three prairie provinces. The study proposed three open-ended questions to individual interview participants: What are the unique needs of victims of interpersonal violence living in rural and northern regions of the Prairie provinces and the North West Territories? What are the gaps that exist in meeting these needs? How do we create non-violent communities in these regions? The same questions were again asked during the face-to-face focus group interviews conducted several months following the individual interviews. In Saskatchewan, a total of twenty-eight telephone interviews, fourteen of which came from service providers from northern locations, and focus groups in a northern and rural location were also conducted.

We authors have drawn on Indigenous and postcolonial scholars to situate our data and study in the white-settler colonial context of Canada. We also have drawn on theories of violence that show the complexity of interpersonal violence. The theoretical lens employed in this chapter is feminist poststructural as it allows for an intersectional analysis that pays attention to how socially constructed categories such as gender, race, indigeneity, sexuality, able-bodiedness, and geopolitical location intersect with power that provides access to limited and valuable resources—however those resources are defined. With power differentials in mind, the analysis examines violence in the context of northern Saskatchewan, asking how past and present colonialisms continue to shape that violence, and how colonialisms intersect with and shape interpersonal violence. Equally, we ask how white-settler gender ideologies, and their accompanying conceptualization of proper masculinity and femininity, come into play in the discursive formation of violence as it plays out in northern Saskatchewan.

Linked to the feminist poststructural analysis is an effort to bring a harm reduction approach to interpersonal violence. A harm reduction approach is the effort to reduce the harm without dismissing or diminishing the harm done. The effort is to recognize the potential for further harms beyond the initial harm and ask how the harm can be reduced (Marlatt, Larimer and Witkiewitz 2012, 5). Moving beyond the discourse of victimizer and victim, a harm reduction approach takes into account the complexity of the event of violence (Stancliff et al. 2015, 207). Aron Shlonsky, Colleen Friend, and Liz Lambert have written that a harm reduction approach to interpersonal violence takes a realistic approach insofar as conditions for, and events of, violence cannot be completely eliminated: “if we cannot hope to stop all forms of abuse, does it make sense to reframe “success” in this area as being the reduction of violence and the minimization of harm” (2007, 356)?

Case Study Issue questions/statements

As violence is at the center of this case study, it is necessary to ask what we are talking about when we use the terms violent and violence, and how then has the understanding and discursive framing of violence shaped responses to it. How has this framing shaped the discourses of intimate partner and family violence (IP/IV)? How has this framing shaped responses to IP/FV? How does introducing a harm reduction model alter IP/FV discourses?

Case Study Research questions/statements

Specific research questions are: What is the historical context of northern Saskatchewan? How has colonialism shaped northern Saskatchewan? How does it intersect with and shape gender ideologies in northern Saskatchewan? How do the above define and shape IP/FV in northern Saskatchewan? And finally, what can a harm reduction approach bring to understanding and responding to the needs of those caught up in interpersonal violence?

Theorizing violence

Violence, wrote Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Phillippe Bourgois, is an unstable concept, one that is “non-linear, productive, destructive, and reproductive. It is mimetic, like imitative magic or homeopathy” (2004, 1). They argue that violence is difficult to define as it is multiply manifested being structural, subjective, symbolic, psychic, and depending where one stands, perceived as productive or destructive, legitimate or illegitimate (2004, 2). Understanding that the interpretation of violence can change depending on situatedness, they further argue that violence is often a response to larger social conditions, making violence “seem like the only possible recourse” (2004, 3).

Slavoj Žižek argues that although subjective violence, for example, interpersonal violence, is the most visible form, there are two other “modes of violence” that are often overlooked. These overlooked aspects are “objective violence,” which is systemic, and symbolic violence, which “is embodied in language and all its forms . . . [it is] our ‘house of being’ ” (2008, 1). As an aspect of object violence, symbolic violence is constitutional to the state on all levels of its operation as well as to larger global systems (2008, 2).

The contexts that comprise our very sociality are encoded with symbolic and systemic violence. Furthermore, systemic or state violence, is coded as non-violence, and seen in actions against citizens, actions like the killing of a “suspect” presented as “defence of society” and therefore not violence in and of itself. The violence staged by the state is coded as non-violence so that, for example, the brutal beating of Rodney King in March 1991 was presented as non-violent in the courtroom. Officer Powell, who struck King forty-six times with his baton, claimed he did so in order to “knock him down from the push-up position, back down onto the ground where he would be in a safer position” (Feldman 2004 [1994], 210). Indeed King was repeatedly presented as the site of violence that had to be contained by four members of the Los Angeles police department who repeatedly beat Rodney King (Feldman 2004 [1994], 213).

Žižek argues that part of, but equally separable from objective violence, is symbolic violence, which is performed in our linguistic, representational, and gestural systems and practices. Pierre Bourdieu wrote that symbolic violence “is a form of power that is exerted on bodies, directly and as if by magic, without any physical constraint” (2001, 38). That is, our very being in all aspects is shaped within a habitus wherein we are located and locate ourselves in relation to the ideologies—gender, economic, racial, sexual, age, etc.—that comprise said habitus. It is in the quotidian we learn to exist in accordance with the rules and regulations of our social body, our habitus, and as such “social law is converted into an embodied law” (Bourdieu 2001, 39).

Interpersonal violence[2]

Gendered violence, although having a long history in human relations, came under the purview of Canadian federal and provincial law over the period of 1983 until 1986. The authority given to the white settler male/masculine in the Canadian context has changed over time, and also demonstrates variation with regard to location. For example, with the emergence of women’s/feminist movements and the Indigenous peoples movements in the 1960s and 1970s, the authority of the State based on white settler masculinity and its explicit statement of (proper, that is, hetero, white settler) men as its legitimate heirs and actors was challenged. Federal and provincial governments began to shift away from thinking about the majority of its populations as normatively subordinate to white-settler, heterosexual masculinity. Nonetheless, even as violence against women, female spouses, and girls was problematized, particularly with Canada’s role in and adoption of the 1993 UN’s Convention on the Elimination of violence against women, violence continued as social censure of it was often conflicted and contradictory. Violence against the female/feminine was criminalized, but humans marked as female/feminine were formally and informally held to views that tended to mitigate the application of laws against this kind of violence. For example, although the state of Texas ratified its laws to include violence against women in 1994 and again in 2000, a thirty-year old white man was cleared of murder after the Texas court determined that his actions were justified since the woman he killed took his money ($150.00) but refused to have sex with him (Moran 2013).

The representation of masculinity as naturally prone to violence influences how intimate partner and family violence are understood. Within a frame of heteronormativity, intimate partner and family violence are instances of the emergence of normative masculine rage that has been provoked into appearance[3]. The provocation of these actions can be many things, but the outcome of violent, masculine rage is taken to be a reasonable response to the situation at hand. The links between masculinity, violence and rage continue to operate normatively as part of current neocolonial gender ideologies. This is not to say that intimate partner and family violence are accepted in Canadian social bodies; rather, intimate partner and family violence are often taken to be normative outcomes because of an implicit understanding that violent rage is naturally—that it is a biological reality—declined in the masculine. Women have abused men (and other women), although in significantly lower numbers (reported spousal violence in Canada 2014, Female 32,205 and Male 8,645) (Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics 2014, 39), and with less deadly outcomes (Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics 2014, 8). Yet, they continue to be viewed as victims and provocateurs rather than perpetrators of violence. However, humans marked as female/feminine are not victims by nature (a synonym for victim is “dupe” which speaks to the negative declension of this category). Rather, their numbers are greater in terms of reports of intimate partner and family violence because of an uneven distribution of power in the social body: folks who have less social power/status depend on the government and its resources, such as the police, to balance out the play of power—or, at least, that’s the hope.

Context

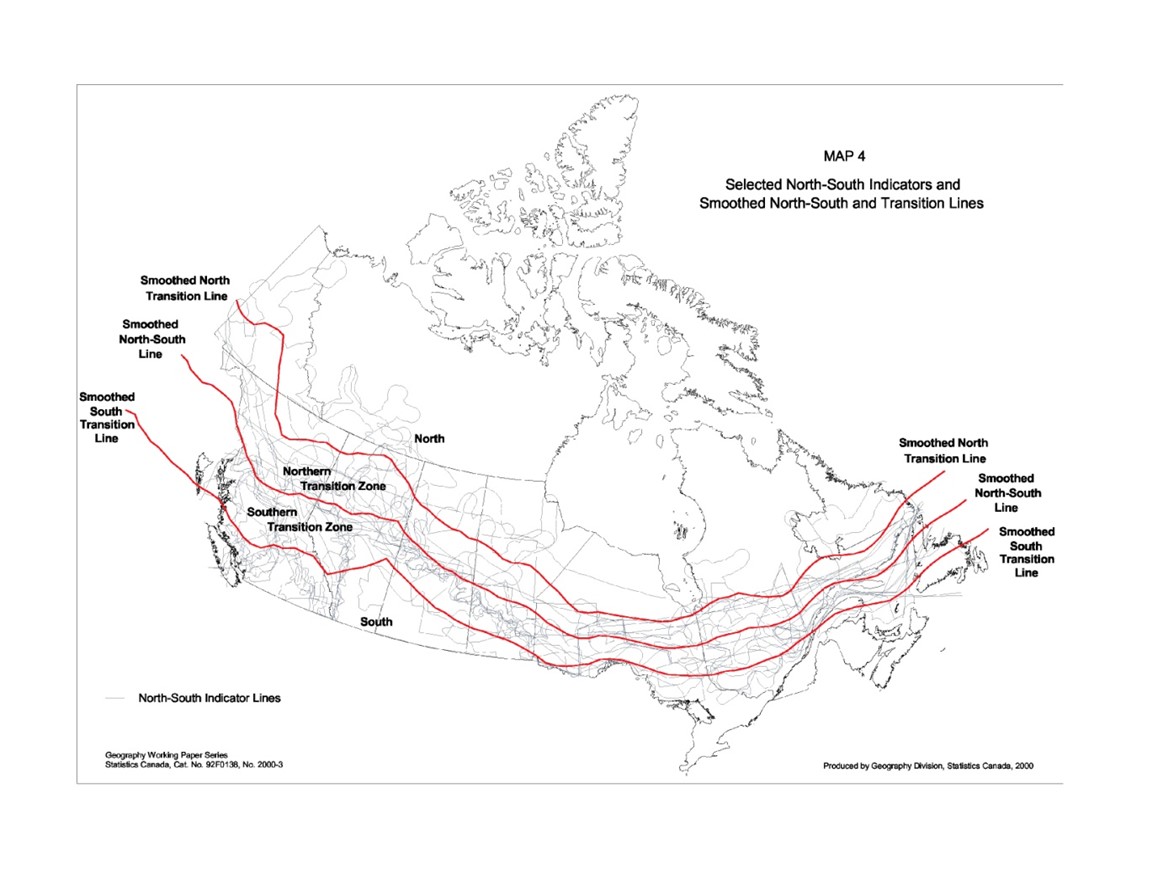

The context of this case study is northern Saskatchewan, a designation of a spatial divide between the developed south and underdeveloped north—underdeveloped in terms of infrastructure that supports and sustains communities. In Saskatchewan the line that marks this divide, running east to west, is just beneath Cumberland House and extends to Green Lake.

Figure 1: North-south divide (map creator Dr. Paul Hart)

The Canadian north is composed of dynamic communities that share some aspects of the prairie south but are also markedly different. Although there are shared aspects between northern and rural communities insofar as they are remote and have fewer services than one would find in an urban location, there are differences as well. These differences need to be accounted for to acknowledge the realities of the challenges northern communities face such as the lack of good housing; affordable healthy food choices; education opportunities; the itinerant work lives of many community members; the harshness of the climate and its social, psychical, and economic demands; and violence—objective, subjective, and symbolic. Ignoring the differences obfuscates these communities and challenges they face.

The history of northern Saskatchewan, as with all of Canada, is one shaped by English and French colonialism. It is a history steeped in the blood of Indigenous peoples whose lands and lives were delimited by the influx of Europeans. Initially, colonialism consisted of tenuous relations of exchange between Indigenous peoples who inhabited the land that would, in time, be called Canada and European newcomers. However, conflict between French and English in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and then between Britain and what would become United States in the eighteenth century, brought about numerous divisions and numerous acts of colonial violence perpetuated against Indigenous peoples by both the colonizing British and French (Juschka 2017).

As white-settlers and their governments and armies moved west, Indigenous peoples were pressed to take up white-settler ways or were moved to reserves, while those who persisted in demanding treaty be respected were more often than not ignored, dismissed, and, in some cases, criminalized (Turpel-Lafond 2000, 76–79). Colonialism in Canada took the form of taking Indigenous lands and relocating Indigenous Peoples to reserve lands and of control over individually allotted land that was coercively appropriated by a government seeking the surrendering of Indigenous lands for white-settlers (Turpel-Lafond 2000, 79). In an attempt to eradicate Indigenous cultures and subsequently assimilate Indigenous peoples as an underclass, denomination residential schools were founded in Canada, and Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their homes and deposited in these badly constructed and isolated schools where they too often faced starvation, malnourishment, emotional, sexual, cultural, psychological, linguistic, and physical abuse (Honouring the Truth 2015; Adams 1996; Eigenbrod 2012). Other sites of oppression include the effort to control Indigenous women’s reproduction, often through sterilization (Caprio 2004; Pegoraro 2015) and, linked to this, the abduction of Indigenous children during what was called the “1960s baby-scoop” (Green 2007; Juschka 2017). Further sites of oppression include the criminalization of Indigenous Peoples (Razack 2015), their continued under representation in sites of power in the Canadian socio-political landscape, and their over representation among the impoverished, alienated, disenfranchised, and the marginalized.

If colonialism shaped the landscape of Canada, this was even more marked in the northern areas of the prairie provinces such as Saskatchewan. As urban centres sprang up in the southern regions of Canada, the north became the site of small remote communities, many of which were cut off from southern regions of the provinces. La Ronge, for example, was not connected until 1948 when a gravel road was laid (Bone 2005, 14). But these connections, as limited as they were and remain in 2017, are less concerned with connecting the peoples of the north and the south as they are with the extraction of wood, minerals, and other valuable commodities for the southern-facing white settler provincial and federal governments. As Robert Bone has noted, the tendency is to extract from the north but never settle the north in a sustained fashion (2005, 13–14).

Along with geographical differences, there are demographical variations as well. In northern Saskatchewan, the population is less dense and has a larger and faster growing Indigenous population who are also younger on average than white settler populations in the north and the south (Flanagan 2017, 1). While the south of Saskatchewan grew with the influx of white settlers from eastern Canada, Europe, and the United States, the population in the north grew naturally, particularly among Indigenous peoples. Equally, migration affects population numbers in the North as Indigenous folks moved south to take up waged employment or to access education, health care, and other social amenities available in the south, while resource industries, such as uranium mining or oil sands, for example, rise and fall in relation to the global market affecting people’s livelihood and propelling them toward the south (Bone 2005, 16–22).

Northern Telephone Interview

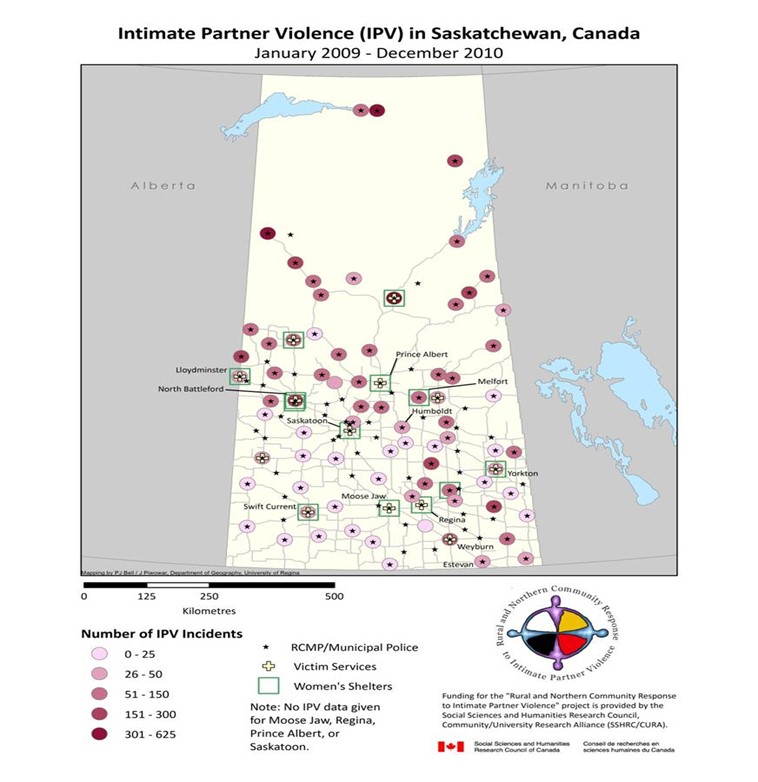

Figure 2. Incidents and services of Intimate Partner Violence in Saskatchewan

The maps developed for this project charted incidences of violence and interpersonal violence services. The map of Saskatchewan (maps were developed for each region within the study) provides a visual that makes clear how northern (and rural) locations were, in many ways, under siege with some locations having incidences of violence that exceed the population of the community. One participant who works in a remote northern location in Saskatchewan commented that there is “lots of violence. . . . [This is] the first time in two and a half years I’ve seen a reduction in prisoners, we’re just shy of 1300. And the two previous years [2012 – 2011] it was 1500 [and] there’s only 2000 people” (Participant 2).

In Saskatchewan twenty-eight telephone interviews were conducted over approximately six months in 2013, and, of these, seventeen were from service providers working in northern locations. The participants were male (six), female (eleven), white-settler, Black Canadian (one) and Indigenous (five). Six of the participants were RCMP officers, four were shelter directors and/or workers, three were victim services workers, one was a family-based victim service provider, two were health care workers, and one was a registered nurse. Saskatchewan coded interviews according to geographical location keeping west and east in mind. The open codes were identified by researchers and community partners working together. The open codes are too numerous to enumerate but include safety plans; housing needs; partnerships among agencies and case planners; access to child care, transportation, pro-active policing and services, support groups, healing lodges, and elders trained about interpersonal violence; insufficient EIO enforcement; and the need to heal from colonization.

The codes made apparent the difficulties faced by service providers in northern Saskatchewan with two primary codes of “under-resourced” and “overwhelmed”: “You know, ever since when I was small, I saw abuse happening. Ever since I can remember, I’ve seen people, women getting beaten, and there was no place for them to go” (Participant 10). Although there are shelters in northern Saskatchewan, these are few, frequently full, and often well removed from their home community. Removal from the community to a shelter also has its problems, as noted by participant six: “when I look at some of the northern communities . . . these women have nowhere safe to go, and if they do wish to go to a shelter of some sort . . . then they’re displaced from their extended family. They have to pick up the children, and basically live out of their suitcase while the offender gets to stay in that community.”

The problem of alienation links to a broader problem—the model of the patriarchal family with the male/masculine seen and treated as the sole proprietor of the house/home. This view of masculine prerogative is commonly held by the Canadian and Saskatchewan governments and the services they support and, as such, acts as objective systemic violence. The masculine prerogative takes the actions of the male/masculine as proper and normative so that challenging the prerogative requires special pleading on the part of those subjected to the deployment of patriarchal power. From the outset, then, those who do not occupy the default location are subject to its rules of power and must demonstrate that the particular “man” has aberrated from the normative male/masculine. Interestingly, Emergency Intervention Orders (EIOs) ignore the masculine prerogative and instead remove the perpetrator of violence from the home and leave those injured, in this study the female parent and children associated with her (if any), in the home and community. However, as noted by participants the EIO is infrequently used and is not applicable on reserves.

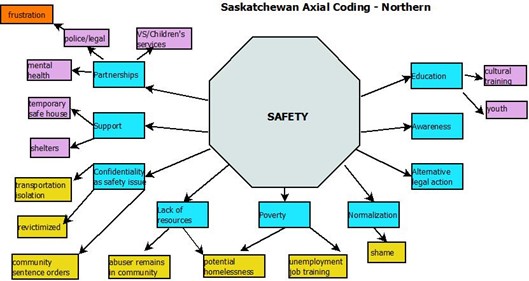

The open codes were subsequently subjected to axial coding. Axial coding requires that researchers abstract the open codes identifying larger categories. The primary axial code designated for Saskatchewan was “safety.” The visual schematic that was developed (see Figure 3), assisted us in visualizing the relationships between our axial code and our open codes. In the Safety schematic, our primary axial code, is at the center around which the open codes are clustered. For example, safety is connected to the open code partnership, and partnership is linked to the open codes of police/legal, mental health, victim, and children services. The diagram is neither explanatory nor does it identify causes; instead, it demonstrates the complexity of interpersonal violence in northern Saskatchewan.

Figure 3. Northern Axial Code Safety

Other axial codes determined by the researchers and service providers were education, perception of intimate partner violence, lack of resources, legal and policing, partnerships, and support. Open codes were organized under each of these axial codes.

The axial codes, open codes, and maps provided researchers with a complex view of the interpersonal violence. Although desiring to keep those victimized by interpersonal violence safe, our data make apparent the difficulty of leaving violent relationships; so difficult that women did not leave or returned as soon as the violent event had ended. “I would say that the victims don’t cooperate because they’re afraid would be the biggest thing, I would think. Yeah, and I know one couple we’ve dealt with repeatedly is she relies on him, financially so she’s, you know, she says ‘how can I testify against him, I need him, he provides for me and my family’ ” (Participant 14).

It’s not unusual to hear the moms say, “You know, I don’t have any food; I’m running out of Pampers, I don’t have any money, and I have no place to go” (Participant 21).

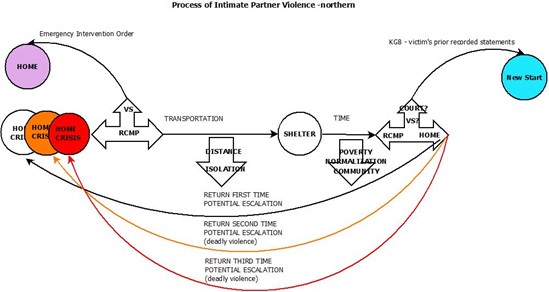

Figure 4. Process of leaving an abusive relationship.

Figure four represents the process of leaving an abusive relationship, beginning with the first reported incident. The diagram represents three routes: one is the Emergency Intervention Order and is the least commonly used; another is returning to the home where violence often escalates and may become deadly; and the third is a “new start.” Represented underneath the process line are constraints that act as obstacles such as fear of poverty. Other constraints are everyday violence that accompanies daily activities such as working, sleeping, eating, and interacting with family and friends, which normalizes the violence. Communities can also act as constraints insofar as they can and do take sides in prosecuted cases of interpersonal violence, which can then leave the community divided. In other instances, the violence is ignored and, as such, erased. Participant 19, a health care worker, commented with regard to the normalization of violence that “It’s normal. Yes. Well, I would say about 90% of the women here within the community have experienced some sort of domestic violence.”

Coding Family Violence

To further code family violence, we organized our open codes into two categories, objective, which includes symbolic, and subjective violence. Objective violence is inherent to the context itself, taking the forms of ideological and systemic violence, both of which are unstable and in flux. Symbolic violence, seen in the representation of interpersonal violence in media, obfuscates objective violence and effectively locates interpersonal violence with persons, making the violence an anomaly. and locating it as bad with State violence enacted against it as good. Subjective violence is violence performed/enacted by a social agent.

Objective violence

The codes that speak to objective violence are cyclical, generational, lack of attention to dating violence, lack of counselling services for children, deracination of those who have suffered violence, and prioritizing the needs of the male/masculine gender. For example, men generally own the home, so the abuser remains in the community and abused women and children must leave. Situated in the community, his narrative is often given credence. A high percentage of victims return home because they miss their homes; experience systemic poverty and must rely on social services; or cannot find a job and so fear homelessness. They also deal with the effects of colonization; the lack of cultural training/understanding of Indigenous and small community kinship systems; a reduced social network, leaving them with no one to call for help because of pressure of the community; mistrust of governmental systems; abused seen to be the problem, “Get women into counselling right away.” Further aggravating their precarious situation, family members are criminalized, that is there is “no alternative to legal action”; and blame and shame which all parties carry in connection to the violent event: the perpetrator risks the shame of being designated a bully and the blame of emotionality, that is he lost control of his emotions (Giordano et al. 2015, 11–12), while the abused person endures the blame and shame attached to “the victim” who is too often situated as a provocateur and/or a “dupe” of violence, while children are perceived as “victims” who may well upon maturation reproduce violence in their own relationships.

Symbolic violence upholds and obscures objective violence insofar as media frequently represent interpersonal violence as always and only subjective. They may at times speak to the significant numbers of “domestic violence” in Saskatchewan, but rarely speak to systemic state mechanisms such as neocolonialism, southward facing politics, the under-resourced and exploited north, patriarchal family relations, the disenfranchisement of abused persons (and children) from their home, or even frontier justice. Again and again, the media assume that interpersonal violence is subjective, involving two (usually heterosexual) people.

Subjective Violence

Subjective violence is violence performed and enacted by individual subjects who are themselves shaped within a context of objective and symbolic violence and who enact this violence in accordance with the normative rules of the larger social body. In a gender ideology wherein the masculine normatively (and naturally, as is often understood within this framework) dominates the feminine, those marked as properly masculine are authoritative, while those others, the victimized, lack such privileging. Intersect Indigeneity with gender and not only is authority of narrative further removed, but it is made impossible as the model of indigenous femininity in white settler masculinity, as found in Canada, is one of an inability to speak the truth (Smith 2003; Stote 2012).

Against such odds, the sufferer of violence must speak their story of the violent event take on both shame and blame in lesser or greater degrees depending on how much her story gains a hearing and is taken to be credible. Partners and families who experience violent events are subject to social shame as their family, that is private, affairs have been exposed to the community at large. Although certainly all homes engage violence of some kind or other, that violence is obfuscated and negated by the exposure of private violence.

Family and intimate partner violence are stigmatized, particularly in small northern communities. Connected to the stigmatization is the threat of the loss of children to the state, along with home and community. Violence in the home can well mean children are removed from the home and the sufferer of violence experiences more loss and further violence, this time by the state. Indigenous women do not trust colonial systems even if advocates and workers in these systems are trying to support them. Too often, support has turned into a situation of further loss for those who have suffered family and intimate partner violence. Subjective violence also entails mental health issues such as attempted suicides, rage, despair, hopelessness, and distrust because the system, legal and otherwise, operates behind closed doors, which can mean the re-victimization of people these social systems are meant to assist.

Conclusion

When asked to identify the gaps in meeting the needs of those in situations of IP/FV, participants came up with a number of clear issues: the persistence in linking male/masculine to property and the subsequent disenfranchisement of female/feminine. For example, Emergency Intervention Orders that remove the violent offender are not the default action and are not applicable on reserves. Participants spoke of a lack of viable and sustained intimate partner and family violence resources and services, in particular, culturally competent services in northern Saskatchewan. Linked to this problem is a lack of commitment on the part of provincial and federal governments to northern communities of Saskatchewan reflected in problems such as the lack of infrastructure, healthy food choices, housing, and a hopeful future.

In asking how we create non-violent communities, we wondered if we had asked a viable question. If non-violent communities do not exist, how do we anticipate such a social formation could be created in northern Saskatchewan? Objective and symbolic violence preclude the possibility of non-violence and indeed provide the rationale for enacting subjective violence in the form of dating, intimate partner, and family violence. With this in mind, we might shift our question: Knowing subjective violence is upheld and justified by objective violence, how can subjective violence be met with a non-violent response in northern Saskatchewan communities?

Seeking a non-violent response operates within the frame of a harm reduction model rather than a criminal justice model. A harm reduction model seeks to reduce harms rather than increase them through criminalization. A harm reduction model requires those harmed to identify the harms and determine how they might be met with a non-violent response. For example, the majority of participants made abundantly clear that the criminalization of those who enact violence created more harm than it reduced. For example, the female recipient of the violence and children lose their home and community, her story is muted, his voluble presence garners community sympathy, her absence from the community creates enmity because she is now an outsider, and the violence becomes her shame and blame. The current model of criminalization deracinates and potentially impoverishes the person(s) most vulnerable, while she and her children are also criminalized insofar as they are moved through the criminal court system and experience further harm. Down the path of poverty that often accompanies women and their children leaving violent relationships can be found further harms such as addictions, self-abuse, lose of children, and homelessness. A harm reduction perspective and a healing approach, then, to intimate partner and family violence might well be a means by which to reduce the harm identified. Resources and support for communities to reduce harm and maintain health need to be properly distributed and sustained to allow for community success to understand and mitigate intimate partner and family violence. Part of the harm reduction approach is also to emphasize education to further reduce harms.

References

Adams, David Wallace. Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience 1875–1928. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1996.

Bone, Robert M. “Saskatchewan’s Forgotten North: 1905–2005.” In Perspectives of Saskatchewan, edited by Jane M. Porter, 13–35. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 2005.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Masculine Domination. Translated by Richard Nice. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001.

Butchart, Alexander, and Christopher Mikton. Global Status Report on Violence Prevention 2014. Violence and Injury Prevention and Disability. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2014. Accessed http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/status_report/2014/en/.

Canadian Centre for Justice Statistics. Family Violence in Canada: A Statistical Profile, 2014. Juristat. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada, 2014.

Caprio, Myla Vincent. “The Lost Generation: American Indian Women and Sterilization Abuse.” Social Justice 31, no. 4 (2004) (98): 40–53.

Eigenbrod, Renate. “ ‘For the Child Taken, for the Parent Left Behind’: Residential School Narratives as Acts of ‘Survivance.’ ” ESC: English Studies in Canada 38, no. 3–4 (September/December, 2012): 277–97.

Feldman, Allen. “On Cultural Anesthesia: From Desert Storm to Rodney King.” In Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology, edited by Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Phillipe Bourgois, 207–16. Malden, MA; Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

Flanagan, Tom. “Incentives, Identity, and the Growth of Canada’s Indigenous Population.” Vancouver, BC: Fraser Institute, June 21, 2017.

Giordano, Peggy C, Wendi L. Johnson, Wendy D. Manning, Monica A. Longmore, and Mallory D. Minter. “Intimate Partner Violence in Young Adulthood: Narrative of Persistence and Desistance.” Criminology 53, no. 3 (August 1, 2015): 330–65. Accessed doi:10.1111/1745–9125.12073.

Green, Joyce. “Balancing Strategies: Aboriginal Women and Constitutional Rights in Canada.” In Making Space for Indigenous Feminism, edited by Joyce Green, 140–59. Winnipeg, MB; London, UK: Fernwood Publishing; Zed Books, 2007.

Juschka, Darlene M. “Indigenous Women, Reproductive Justice and Indigenous Feminisms: A Narrative.” In Listening to the Beat of Our Drum: Indigenous Parenting in a Contemporary Society, edited by Carrie Bourassa, Betty McKenna, and Darlene Juschka. Toronto: Demeter, 2017.

———. Political Bodies/Body Politic: The Semiotics of Gender. UK: Equinox, 2009.

Lightfoot, Nancy, Roger Strasser, Marion Maar, and Kristen Jacklin. “Challenges and Rewards of Health Research in Northern, Rural, and Remote Communities.” Annals of Epidemiology 18, no. 6 (June, 2008.): 507–14.

Marlatt, G. Alan, Mary E. Larimer, and Mary E. Witkiewitz, eds. Harm Reduction: Pragmatic Strategies for Managing High-Risk Behaviours, 2nd Ed. New York; London: The Guilford Press, 2012.

Moran, Lee. “Texas Prostitute’s Jilted Killer Acquitted, Was Trying to ‘Retrieve Stolen Property’ Says Jury.” Daily News, June 2013. Accessed http://www.nydailynews.com/news/crime/jilted-john-acquitted-texas-prostitute-death-article-1.1365975.

Mosher, Janet, and Pat Evans. “Welfare Policy: A Critical Study for Women’s Safety.” In Women in a Globalizing World: Transforming Equality, Development, Diversity, and Peace, edited by Angela Miles, 138–46. Toronto: Inanna Press, 2013.

Pegoraro, Leonardo. “Second-Rate Victims: The Forced Sterilization of Indigenous Peoples in the USA and Canada.” Settler Colonial Studies 5, no. 2 (2015): 161–73. Accessed doi:DOI:10.1080/2201473X.2014.955947.

Razack, Sherene. Dying from Improvement: Inquests and Inquires into Indigenous Deaths in Custody. Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Scheper-Hughes, Nancy, and Philippe Bourgois. “Introduction: Making Sense of Violence.” In Violence in War and Peace: An Anthology, eds. Nancy Scheper-Hughes and Philippe Bourgois, 1–32. Malden, MA; Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2004.

Shlonsky, Aron, Colleen Friend, and Liz Lambert. “From Cultural Class to New Possibilities: A Harm Reduction Approach to Family Violence and Child Protection Services.” Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 7, no. 4 (November 2007): 345–63.

Smith, Andrea. Conquest: Sexual Violence and American Indian Genocide. Cambridge, MA: South End Press, 2005.

———. “Not an Indian Tradition: The Sexual Colonization of Native Peoples.” Hypatia, Indigenous Women in the Americas 18, no. 2 (Spring 2003): 70–85.

Stancliff, Sharon, Benjamin W. Phillips, Nazlee Maghsoudi, and Herman Joseph. “Harm Reduction: Front Line Public Health.” Journal of Addictive Diseases 34, no. 2-3 (2015): 206–19.

Stote, Karen. “The Coercive Sterilization of Aboriginal Women in Canada.” American Indian Culture and Research Journal 36, no. 3 (2012): 117–50.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada Honoring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Winnipeg, MB: The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015.

Turpel-Lafond, Mary Ellen. “Maskêko-Sâkahikanihk, One Hundred Years for a Saskatchewan First Nation.” In Perspectives of Saskatchewan, edited by Jene M. Porter, 75–104. Winnipeg, MB: University of Manitoba Press, 2000.

Žižek, Slavoj. Violence: Six Sideways Reflections. New York: Picador, 2008.

- I have opted to use the phrase interpersonal violence rather than intimate partner violence as the former includes within its meaning frame, according to the World Health Organization, intimate partner violence, family violence, youth violence, violence against women, child maltreatment, and elder abuse (Butchart and Mikton, 2014, 2). Within this larger category of violence, this chapter examines intimate partner violence and family violence (referred to as IP&FV throughout this chapter). ↵

- Conceptualizing IP/FV as subcategories of interpersonal violence is useful in the context of northern Saskatchewan since interviews with service providers made apparent there were more than just two people involved in the conflict. In small, remote and/or isolated communities, rarely are only two people involved in the event of violence. With this in mind, then, including family violence along with intimate partner violence allows the researchers to understand that all members of the family are affected by family violence when it occurs, such as children, siblings, older dependent parents, cousins and, other extended family members (see also Lightfoot, et al. 2008, 507). ↵

- This is so even if enacted by women since intimate partner and family violence are seen to be the prerogative of the masculine. See for example the study of Peggy Giordano et al. wherein a female perpetrator of intimate partner violence commented that she felt like the “incredible hulk” during her rages against her partner (2015, 18). The hulk is a decidedly masculine anti-hero whose rage is generally put into the service of the “good” when properly domesticated, typically by a human marked as female/feminine. ↵