Reframing Assessment

12

Mary M. Rowan, Carol Flaten, Lori Rhudy and Nima Salehi

Keywords

digital technology integration, psychomotor skills video, self-assessment, peer feedback, reflection, instructor feedback, video annotation

Introduction

In 2007 the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching established a program for the comprehensive study of preparation in five professions, including nursing. In the report on nursing education, the researchers noted that graduates of nursing programs are “ill-prepared for the profound changes in science, technology and the nature and settings of nursing practice” and made several recommendations for transforming nursing education (Benner, Sutphan, Leonard, & Day, 2010). At the time, Benner et al. found that much of the academic work provided theoretical knowledge for nursing but clinical practice was not well integrated. Faculty were encouraged to look for ways to more closely tie coursework to what actually happens in patient care. One of the specific recommendations was for increasing experiential teaching and creating opportunities for situated cognition, thinking-in-action, to address students’ need to understand the scope and purpose of nursing care interventions and how to analyze their own progress toward achieving safe patient-care goals. Furthermore, making explicit the connections from classroom content and laboratory practice to actual clinical performance would help students move beyond acquiring knowledge into actions requiring students to us knowledge, thereby integrating the academic work with clinical practice (Benner et al., 2010).

The Carnegie report catalyzed our school to complete a major redesign of the curriculum with a plan for a shift in the approach to experiential learning activities. At about the same time, the School of Nursing initiated a significant remodel of laboratory and classroom spaces and redesigned some of the teaching strategies used in the new spaces. Plans included increasing the use of flipped classroom techniques, metacognitive activities, and opportunities for reflection. Shortly after the school’s newly redesigned laboratory opened, the authors received a grant to develop learning activities using digital technologies designed to enhance teaching and learning. One part of this grant project was the integration of student use of tablet computers for video recording of basic nursing skills as a form of performance evaluation and as a way to extend learning beyond the actual hands-on practice time spent in the laboratory. The pilot project for using video plus annotation is reported here.

Use of Video Recording and Annotation

Video of performance has long been used as a way to document progress and as a tool for providing peer or instructor feedback. In health sciences, video is often used as a component of high fidelity simulation experiences. However, the authors could find no published examples of the use of video in the context of a basic nursing interventions laboratory or examples of recordings paired with annotation as a reflective activity.

Assisting students in their development as reflective practitioners has long been a challenge in undergraduate education. Metacognitive strategies are commonly used in classroom settings to deepen learning, but are less likely to be used in laboratory courses. The focus in most nursing lab courses is to teach students how to perform basic nursing interventions and psychomotor skills.

Laboratory courses in nursing consist of experiential activities and a type of virtual clinical practice. The laboratory environment provides students with safe and accessible exposure to health care skills practice in order to prepare them for actual patient care in clinics, hospitals or home care settings. The laboratory experiences are typically limited to a few hours each week. Instructors have been challenged to find ways to extend the learning beyond the actual hands on practice during the lab session. Although video has long been used in education, the relatively recent availability of easy-to-use video annotation tools provides new opportunities (Rich & Hannafin, 2009). Integrating video and annotation activities for self-evaluation, peer response and instructor feedback provides students with a way to extend and enhance the impact of laboratory practice. In addition, video recording of psychomotor skills practice sessions provides a concrete review of common health care errors and a more in-depth understanding of how individual students might be able to improve their nursing abilities.

Self-Reflection and Peer Response

Nursing standards of practice in the U.S. are regulated by each state’s Board of Nursing and guided by the state’s Nurse Practice Act. Healthcare professionals (nurses, physicians and other healthcare professionals) are well aware of the need to reflect on and regulate their own practice. Nursing students must learn how to critically reflect on and monitor their practice in order to meet the standards of providing safe, high quality nursing care. There is an expectation that professional nurses will receive ongoing feedback from peers on performance. Furthermore, nurses need to know how to provide feedback to peers. Self-reflection and peer response activities during nursing laboratory courses prepare students for real life peer feedback in the nursing field. For this reason we developed course materials to teach reflection and peer response as part of the video project.

Courses Selected

Two courses were selected for the purposes of this project.

- Assessment and Beginning Interventions: Nursing Lab I

- Nursing Interventions Lab II

These sequential courses are required during the first year of the nursing major, prior to any activities with actual patients. Each of the two courses identified included 7 sections of students, ranging from 15 to 24 per section for a total of 146 students. The ratio of instructors to students was approximately 1:8 in lab sections. Students spend 4 hours per week in the laboratory courses.

Beginning nursing students need to achieve a minimum level of competence before they can begin clinical rotations in patient care settings. The selected courses included a wide range of hands-on practice activities that had the potential to be enhanced by the use of video for performance review.

The intent of the project was to use digital technologies to enhance students’ awareness of their kinetic movements and manipulation of specialized equipment. This increased awareness would provide the platform for critical reflection. A challenge was determining how to integrate video activities into the selected courses. Several questions were identified.

- Recording which nursing interventions (skills) would provide the most benefit to students?

- What types of technologies would effectively support recording, annotating, and sharing activities?

- What preparation would faculty and students need to facilitate these activities?

- How could we assess the effectiveness of these activities?

Faculty believed that teaching certain specific skill sets, such as sterile technique, could be improved. Sterile technique is an example of a complex skill set that requires understanding how one physically moves in and through an environment. Students often underestimate the complexity. Furthermore, faculty were aware that students struggled with sterile technique when they were in actual patient care settings and believed that a video with annotation would offer an opportunity to deepen the students’ mastery of the skills beyond actual hands-on practice in the laboratory. This topic was determined to be an excellent fit for the initial of the use of video paired with annotation for self-review, peer response, and instructor feedback. Other activities such as medication administration, urinary catheterization, and intravenous medication infusion were also selected. These four activities selected for the project are considered foundational skills for nursing practice, and embed the core concepts of sterile technique and safe medication administration. The plan was to limit each video to 3-5 minutes of performance and to focus on components of the skill that students had difficulty executing. The use of video was not initiated until the fourth week of the course to give students time to get acclimated to the lab environment and protocols. (After the initial pilot project the intravenous infusion video recording was dropped since it involved multiple tasks and required longer recording times.)

Activity Logistics and Technology Use

The technology used for video and review included the following:

- Camera “app” on computer tablets (Apple iPad®)

- In class computer and projector (for small/large group debriefing)

- Fuse app for Camtasia (Techsmith® product used to upload video file to media server)

- Media Mill – university media server

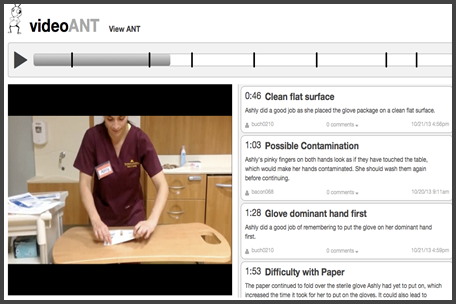

- VideoAnt – web-based annotation application for mobile and desktop devices that was developed at the College of Education and Human Development, University of Minnesota

Faculty designed a developmental approach to introduce the video activities to students. During the first experience, the focus was on using the technology. With each subsequent recording activity, the focus on assessment and reflection increased. Students worked in pairs, with each student taking a turn to practice the skill while their partner recorded the activity using the iPad® camera. If a third student was part of the team, they were directed to observe and take notes for feedback purposes until it was their turn to practice or record. After each activity was practiced and recorded, students met in pairs to watch the videos. Faculty provided a checklist that outlined critical elements of each skill. Students reviewed each video to determine where they had met criteria based on the checklists. Students were also required to assess the video for areas of deficiency. After the initial review students uploaded their video file to a university media server where it was linked to an annotation application and shared with an assigned peer responder, and with the instructor.

Figure 1: Sample of video with Annotation

Links to each video were added to an online collaborative document in the course website. Due to sharing settings in annotation program (VideoAnt), each video linked in the document could only be viewed by 1) the student, 2) the peer response student, and 3) the instructor. Peer responders and faculty would select the video, review it, and annotate the recording to provide feedback based on provided guidelines. Aspects of the skill performed well and areas for improvement were identified.

Originally students uploaded the video files to Media Mill with technical support staff processing the videos, linking them to the web-based video annotation application, and adding links to the course website. This process proved to be very time consuming. During subsequent semesters the use of uploaded video diminished and, instead, emphasis was placed on using time during the laboratory session for students to debrief videos in pairs, then small 8-person groups with the instructor. In the small groups, instructors reviewed one or two of the videos as a basis for discussion and to respond to questions and on skills methods and approaches. To extend the learning, students were required to access their video after the laboratory in order to:

- Complete self-assessment reflection by assigned date

- Complete peer response for partner by assigned date

- View instructor feedback posted later during the week

Preparation and Support for Faculty

At the beginning of the semester the course coordinator and a technology support person met with the instructional team to review curriculum and video activities. The team reviewed assignment guidelines, discussed the purpose of integrating video recording, and practiced using the iPad® and VideoAnt annotation applications. An instruction guide was developed and provided for each application and the plan for technical assistance and support was described. All support materials were available to the instructional team and the students in the course website. Meetings to review plans for using VideoAnt technology were also scheduled for later in the semester.

Preparation and Support for Students

Students were provided an overview of the purpose of video activities at the beginning of the semester. (Sample information in Appendix A.) The planned activities were identified in the weekly course outline accessible via the course learning platform. Course content was adapted to include information about the purpose of the video integration, self-assessment, peer response and instructor feedback. Clear, concise one page instructions were provided for the use of the iPad® and the process for uploading the recordings to the media repository. A sample video of the activity was linked in the directions on the course website. Another instruction document guided them through using the VideoAnt annotation application. Technical assistance was provided during each video-enhanced lab session. A tech support email and phone number was provided for the online self-assessment and peer response annotation activity that students completed after the lab session.

Evaluation Data

Students were given surveys pre and post video recording activities at the beginning and the end of the semester for both courses. The pre survey provided baseline information. The post survey results after the first course showed an increase from pre to post responses indicating agreement with the benefits of video recording, self-assessment, and instructor feedback. Students were less positive about the benefits of peer response. This was also reflected during follow up focus group sessions with students noting that peers needed more instructor modeling and overall training to provide effective review responses. Survey questions and results are in Appendix B.

Student focus group results

Students in focus groups expressed that the video recording process was helpful in learning and reviewing skills practice. They enjoyed reviewing the videos at their own pace. They liked having online feedback from instructors, and said they would like more instructor feedback. Many said they enjoyed both receiving and providing feedback from peers, noting that this gave them greater confidence and helped their learning. Overall focus group participants were happy with the video and annotation activities. Comments from students included:

- The feedback from instructors was really great.

- Good critiques by peers were very helpful.

- Made me more confident, could see improvement

- Enjoyed sharing it with my family. This gave me a feeling of pride.

- VideoAnt was easy to use. I was worried until I used it and then very happy that it was easy.

Faculty Focus Group Results

Faculty focus group results indicated that instructors felt students improved in their ability to provide peer feedback after they viewed faculty feedback. They suggested that faculty model feedback initially before expecting students to provide responses so there would be greater clarity on what constitutes effective feedback. Faculty felt that in-lab debriefing with small groups of 8 students provided the best use of the video activities, with the quality of student questions enhanced by being able to use actual student videos to elicit questions and discussions. Faculty observed that online instructor response using VideoAnt was beneficial but labor intensive, and noted that other faculty assignment feedback could suffer as a consequence. Therefore some time management considerations needed to be taken into account as video recording activities were integrated.

Some faculty mentioned the following:

- Students became more critical in their peer feedback over time.

- Online instructor feedback allows faculty to give more feedback to individual students.

- Online feedback made faculty feel like they were not as “present” compared to providing feedback in person.

- With this activity, instructor feedback was delayed until several days after the lab activity occurred.

Both faculty and students felt that the video recordings provided helpful information about motor skills and about more subtle body language and communication skills. Both focus groups indicated that the smaller debriefing groups of 8 students were preferable to having a larger whole class group for getting instructor input and making students feel comfortable about sharing videos with peers.

Technology Issues

Issues encountered during the video process were with the following:

- Wi-fi connections were not always reliable, requiring students to log back in before continuing an upload to the media server.

- The upload time for the 3 – 5 minute video file was often long, and sometimes file uploads stalled in the process. A workaround for this issue was to have lab and tech support staff upload the video files after students had completed the lab and left the area. Complete technical directions coupled with onsite technical support staff helped mitigate these problems.

- A few students did not add their name or section to the uploaded video title as instructed, so it took some time to locate student and course section names to link it in the proper section of the course site.

- Processing video and using the technology was extremely time-consuming.

- Exploration of ways to streamline the media server upload and processing workflow is ongoing. Determining this workflow needs dedicated time, training and technical support.

Conclusions

Instructors found that the use of annotated video with follow up analysis, self-assessment, peer response, and instructor feedback helped students understand kinetic/movement requirements and how to manipulate equipment. Students also had an increased appreciation for the complexity of the nursing interventions they were learning.

Students valued both the self-reflection and faculty feedback components. Many of them indicated that they wanted more video recording activities and instructor feedback. Students appreciated the opportunity to review their performance multiple times and focus on a different aspect of their performance each time. They felt this was an enhancement that improved performance. Because students were novices, peer feedback in some cases was less valued, and students mentioned that peer response was inconsistent. They suggested some additional modeling or training could enhance the value of peer response. Some students indicated that they weren’t sure what feedback to provide peers even though they had been given a skills checklist and general guidelines to note both areas where tasks were performed well and areas to improve. However, many students indicated that they learned a lot from watching other student videos, in particular that they learned alternate ways to complete health care tasks.

Nursing students need to become adept with complex procedures that include operating specialized equipment, manipulating objects and performing skills while remaining aware of nursing environmental concerns such as protection of a sterile field. Observing recorded activities with guidance directing them to attend to specific behaviors (often unconscious) helped students learn how to perform nursing skills. Students felt that video activities were particularly effective in providing visual feedback on their performance, and that this in turn helped them improve and enhance their abilities.

The general consensus from faculty and students was that use of video technology promotes reflective practice and enhances performance of nursing activities. Incorporating peer observation and response provided valuable immediate input and early socialization to the role they would be expected to play in their professional environment.

Post Project Use of Video Recording and Reflection

The initial project occurred in 2013. Despite the early technical challenges, the activities described proved pivotal in changing the approach used for teaching basic nursing interventions. The value of reflection for enhancing and extending learning was clear. The faculty considered how to build more metacognitive and reflexive activities into the weekly lab sessions and into the high-fidelity simulation experiences that were included in the course. The annotation processes have been changed and improved to make the annotation option less labor intensive. This tool holds promise as an important reflective activity.

Each lab session now ends with a debriefing element. A variety of approaches are used to strengthen the learning from that session. In general, the model used is to consider the activity from three perspectives: Thinking-in-action, Thinking-on-action, and Thinking-beyond-action (Dreifuerst, 2009). Using all three of these elements asks students to consider what they were thinking while they were engaged in the activity, to consider the activity retrospectively, and then to consider what they learned that can be used in the future as they encounter novel situations. It is difficult to measure the results beyond the performance in the actual laboratory course, but clinical instructors are reporting that the students are better prepared and have more confidence in their ability than was observed in the past.

References

Benner, P. Sutphan, M., Leonard, V., & Day, L. (2010). Educating Nurses: A Call for Radical Transformation. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Dreifuerst, K. (2009). Essentials of Debriefing in Simulation Learning: A Concept Analysis. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(2), pp. 109-114.

Rich, P. & Hannafin, M. (2009). Video Annotation Tools: Technologies to Scaffold, Structure, and Transform Teacher Reflection. Journal of Teacher Education, 60, pp. 52-67, DOI: 10.1177/0022487108328486

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Minnesota Provost for the 2013 Enhancement of Academic Programs Using Digital Technology grants program that funded this project. We also wish to acknowledge Dr. Jeff Lindgren, assistant director of the Center for Educational Innovation.

Appendix A

1. Sample Instructions or Self-Reflection/Peer Response

Self-Reflection and Peer Response Overview

In this course you will be completing several learning activities that include self-reflection and peer response. Here is a brief overview of the learning theories and practices associated with this type of learning activity.

What is Self-Reflection?

Self-Reflection is the process where the student who performed an activity or wrote a paper, critically reviews their own work. A set of criteria or guidelines are provided for the student. The student is then able to look closely to identify strengths or weaknesses.

Why is self-reflection important in the learning process?

Self-reflection allows the student to gain greater insight into their own behaviors and decision making process. This ability is a life-long learning skill that will be necessary as new situations are presented to the student/nurse throughout one’s career.

How do I do Self-Reflection?

In your lab or classroom course your faculty will guide you through the self-reflection process. Typically you will have a document that will provide a combination of specific criteria that are important for you to consider in your self-assessment (for example, did you keep the equipment sterile or are your written sentences complete) and criteria that are broader (such as your communication style with the client and/or family). You will likely write a reflection response that identifies insights about observed behavior and how you might approach a similar activity in the future based on this observation.

What is the value of Peer Response?

Peer Response and Self-Reflection are lifelong professional abilities that you will practice throughout your career.

What is Peer Response?

In a lab or classroom setting you will work in pairs or small groups. Within these small groups or pairs, you will observe or read your peers’ work and provide comments back to your peers regarding what you observed. This is an active process for both the student completing the activity and the student providing comments. As a result, both students are actively engaged in the learning process. After you have had an opportunity to do the activity you may also complete a self-reflection activity.

Why is Peer Response Important?

Peer response has been shown to empower learners and improve the quality of learning (Rush, Firth, Burke & Marks-Maran, 2012). Peer response also helps learners develop the skills required to make judgments or decisions that inform critical thinking abilities important in nursing. Students are also able to identify their own strengths and weaknesses, which supports their development in the learning process.

Engaging in meaningful feedback at all levels of learning and in professional nursing practice supports not only the individual nurse but the entire team of health care providers. Practicing peer response as a nursing student is a foundational ability for professional nursing practice.

When and where would Peer Response be used?

As a student you will be provided with activities that will include a Peer Response component. These activities may be in a lab course, classroom course, on-line course or clinical course. Direct observation of an activity such as hand washing technique or reading the first draft of a classmate’s written assignment may be assigned. These activities may occur in or outside of class time. Each instructor will provide specific directions.

What do I know about the activity in order to provide Peer Response?

You may be thinking, “I am not an expert on that activity, how can I provide any meaningful Peer Response comments?” You are smarter than you think! In preparation for activities, you will have read about the activity, likely watch a short video (several times), possibly read a procedure/guideline form, and will use your observation skills. Based on your preparation you will have a good knowledge base from which to provide feedback to a peer. You and your peer or small group will actively be engaged in the learning process.

How Do I Do Peer Response?

Responsibilities:

Come prepared: Complete assigned work before class time.

Review any assigned handouts or guides that help you provide specific comments.

Be respectful of all students in the course. Each student comes to an assignment or activity with a different set of background experiences. Be respectful of differences and learn from everyone’s experiences.

Communication:

Communication is crucial in the Peer Response process. Peer Response needs to include affirming or positive information and information about specific components of the activity that did not work well. Sometimes errors will occur.

Below are a set of suggested responses to help you provide comments to a peer. The ability to provide this type of feedback required in the Peer Response process will take practice. Your instructors will assist you.

Clear, specific comments are the most helpful. For example,

- All of the steps were completed in the correct order

- When you put on the second sterile glove, your right hand touched the table, contaminating that glove.

These comments are more helpful than “Great job!” Other phrases to consider:

- I noticed the cover fell on the floor…

- I am curious about where you placed the sterile dressing…

- The nurse in the video did ___ a bit differently. How did ____ work for you?

Appendix References:

Rush, S., Firth, T., Burke, L., & Marks-Maran, D. (2012). Implementation and evaluation of peer assessment of clinical skills for first year student nurses. Nurse Education in Practice, 12. Retrieved from www.elsevier.com.nepr.

Additional resources that informed this paper:

Boehm,H.& Bonnel, W. (2010). The use of peer review in nursing education and clinical practice. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development, 26(3), 108-115.

Price, B. (2005). Self-assessment and reflection in nurse education. Nursing Standard, 19(29), 33-37.

2. Sample Directions for Activity

Self Assessment and Peer Response Directions

Note: “Patients” are mannequins for this activity

This week you will doing self-assessment and providing peer response for group members during medication administration learning activities. Read the Self-Assessment and Peer Response Guidelines in the General section of the course first. A key concept to remember is that both the student performing the skill and the peer responder will be enhancing their understanding from this analysis.

Self Assessment

During this activity one of your group members will videotape your activity. Afterwards you will analyze the process using the skills evaluation checklist. Provide team members with your thoughts and comments to help them understand your analysis of your performance.

Peer Response

Videotape your partner using provided equipment and direction sheets. After videotaping briefly review skills practice using the video and the skills evaluation checklist. Remember to keep your comments tactful, but provide honest reflections on what you’ve observed.

3. Self-Assessment and Peer Response Examples

Sample Student Self-reflection

I forgot to ask the patient whether she had any latex or iodine allergies. I also forgot to put her legs apart before providing the cleaning care (I remembered in the middle of the process and then I did it). I poured the lubricant on the sterile field but forgot to lubricate the catheter. On the video I could not hear myself well throughout the procedure; however, I remember greeting her and identifying her with two identifiers. I did hand hygiene, provided patient privacy, provided comfort. I was having a hard time putting the sterile gloves. I should have removed my rings before putting the gloves on.

Sample Peer Response

What went well: You entered the room and introduced yourself and performed hand hygiene, which was very good. You verified the patient’s identity and informed them on what procedure they were going to have today. You opened the sterile package properly.

Areas of Improvement

When getting the patient ready to bathe you did not tell her that you were placing a bath blanket on her, and you did not clean her properly with different sides of the cloth so as not to contaminate clean areas. When the catheter kit was open you reached over the kit and caused a break in the sterile field, so be aware not to lean over a sterile field. Also remember to place the patient’s legs in the proper position for cleaning. Assist the patient if needed.

Technical Support

During the first week using video recording the lab assistant will erase all video segments at the end of the session. In subsequent weeks the videos will be uploaded for deeper self-reflection and feedback.

Appendix B: Pre and Post Survey Comparison

- Evaluating a video recording of myself practicing activities in the lab will enhance/enhanced my learning

- I believe that reflecting on my video recorded skill practice is an important learning activity

- Feedback from my peers is/was important to my learning

- Observing a peer’s performance and providing feedback to them enhances/enhanced my learning

- Observation of my own video recorded activity is likely to improve/improved my confidence in my ability to perform that particular activity.

- Reflecting on my own video recorded activity is likely to improve/improved my confidence in my ability to perform that particular activity.

- I regularly reflect on my learning activities in the lab as a way to improve

- (Pre question only) I have used video recording to evaluate my performance.

- (Post question only) Feedback from my faculty was important to my learning

Table 1: Survey Results with Percentage of Students Selecting Each Item

| Percent | Strongly Agree | Agree | Undecided | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | Total | |

| Q1/1 | Pre | 29.2 | 55.5 | 14.6 | 0.7 | 0 | 137 |

| Post | 47.6 | 46.9 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 0 | 143 | |

| Q2/2 | Pre | 28.2 | 53.5 | 16.9 | 1.4 | 0 | 142 |

| Post | 40 | 49 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 0 | 145 | |

| Q3/3 | Pre | 37.2 | 53.1 | 6.9 | 2.1 | 0.7 | 145 |

| Post | 34.8 | 48.9 | 11.3 | 5 | 0 | 141 | |

| Q4 (only post) | Pre | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Post | 76.4 | 22.2 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0 | 144 | |

| Q4/5 | Pre | 36.6 | 59.2 | 3.5 | 0.7 | 0 | 142 |

| Post | 32.4 | 52.8 | 12 | 2.8 | 0 | 142 | |

| Q5/6 | Pre | 31.2 | 50.4 | 14.2 | 4.3 | 0 | 141 |

| Post | 39.4 | 50 | 7.7 | 2.8 | 0 | 142 | |

| Q6/7 | Pre | 25.5 | 61.7 | 10.6 | 2.1 | 0 | 141 |

| Post | 35 | 52.1 | 9.3 | 3.6 | 0 | 140 | |

| Q7/8 | Pre | 19.5 | 78.2 | 2.3 | 0 | 0 | 133 |

| Post | 23.2 | 62.3 | 10.6 | 3.5 | 0 | 142 | |