Chapter 10: Technology Use in Family Health and Money Management

It is easy to sit up and take notice. What is difficult is getting up and taking action.

― Honore de Balzac

Chapter Insights

- Security, safety, privacy, and compliance with policies and regulations are concerns in managing both health and finances through the internet and with digital applications. These can be potential threats to family well-being.

- Applications offered to help families manage finances and/or health care may widen the digital divide.

- Personal expression and the sharing of information about one’s health have become popular, particularly through blogs, video channels (e.g., The Clarity Project), and health apps. Such sharing of personal health experiences has pros and cons.

- Telemedicine has become popular, particularly in the aftermath of COVID-19. There are benefits and possible concerns of telemedicine (or telehealth).

- Apply the criteria of USE (easy to use, safe, effective) to the selection of health care information and financial apps. Consider how easy guidelines like acronyms might be helpful to family members and consumers.

- Among other household expenditures, technology has become a stable and increasingly costly item. Given a list of categories for tech spending, calculate your average monthly and yearly cost of technology. Consider how your own costs compare with others (to identify factors that go into our technology spending, such as sharing passwords to streaming services or free printing). Consider too how your costs compare to other major expenditures, such as college tuition, to gain perspective about family households’ tech spending burden.

- The use of apps like Venmo for money exchange has become popular, as have mobile apps for banking and investments. While these make money exchange and budgeting easier, they also introduce certain risks.

- A family is responsible for teaching children about money management. This can be done by giving an allowance, paying for chores, or setting up a savings account or a spending card. Consider recommendations to help families identify apps that are effective, engaging for children, age-appropriate, and safe.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

Introduction

Without a doubt, ICTs have made it easier for families to search for information and manage data on health and finance, and communicate with related professionals. Looking for a clinic, resolving a question about a child’s health, accessing health records, and making visits to a doctor can all be done online or through an app. Similarly, finding information about investments and retirement savings, accessing bank records, mapping the closest ATM, and even sending money to another person can be done with a few clicks. In this chapter, we briefly explore the range of applications and devices families use to manage their health care and finances, and identify ways in which such use can be positive for individual well-being yet have family impacts as well.

As we consider these topics, we are reminded of our key consideration of equity and access. The digital divide, with its As we consider ICT’s role in aiding our health care and money management and spending, we are reminded that unequal access to digital tools and the internet present challenges, resulting in less efficient record keeping, inefficient tranactions, and the inability to quickly access medical information and more. unequal access to digital tools and the internet, can also affect the ability to keep records, complete transactions efficiently, communicate with professionals, and manage information. Technology literacy (or e-literacy) also influences comfort with using ICT effectively and safely. For example, in 2017, Perezcki et al. determined that, although a large urban health care system offered a patient portal, the majority of adults didn’t use it. Use was even lower for racial and ethnic minorities, those with lower income and education levels, and, particularly, those without neighborhood internet access. Families in rural areas similarly face challenges with accessing health information online (Choi & DiNitto, 2013).

Information on personal and family health and money can be deeply private and sensitive and require confidentiality. For this reason, HIPPA laws (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) were put into place as the internet became more publicly available. Financial data, too, is subject to invasions of privacy and security threats. In 2017, a data breach at Equifax risked credit information on 145 million individuals (including the author). The sensitive data shared included names, social security numbers, addresses, and dates of birth. While for most users there were no serious consequences, the breach did mean that when the immediate fix was to block credit details, individuals later faced challenges in obtaining their own credit information. There is also evidence of the breach’s impact on children (Kim & Capitani, 2017). One family discovered that their 7-year-old’s information was affected, which led them to wonder about the challenges they would face if their Social Security number was exposed.

Family professionals can help families gain basic understanding and comfort using digital tools to manage and understand money and health care. They can also advocate for the full range of families to have equal access to the internet and digital technologies, and to the same efficiencies and opportunities afforded to others. Because privacy and safety are so central to the topics of money and family health, we reinforce our critical lens on technology use by beginning with a focus on this issue.

Privacy and Safety of Information and Data

Privacy and online safety are major issues facing everyone who uses the internet. With regard to family privacy, inclusive

of workplace influences, Ollier-Malaterre and colleagues (2019) note:

technology amplifies the blurring…also because the very definitions of what is public and what is private are under scrutiny: Information shared on social media, for instance, is sometimes deemed by scholars and lawyers as private and sometimes public…. In an era in which putting up curtains on windows and planting high trees around houses no longer suffices to safeguard privacy, many new questions for individuals arise about privacy, visibility, and surveillance that societies or collective actions may at some point strive to regulate. (p. 435)

The use of online technologies enables telecommunication companies’ access to personal data, data that can be sold to market products to individuals and create a digital footprint that individuals and children have no control over. These issues are particularly critical for families. Sharing accounts and information is common within relationships, so compromises to identity, privacy, and security can easily threaten others. And the economic consequence of shared credit card information or an individual’s identity theft on the whole family can be devastating.

These are also family-centric concerns, as it is within the responsibility of parents to oversee children’s safety online and to teach children how to protect their privacy and use sites that adhere to child-protective policies. As noted in Chapter 5, children’s level of development and emerging abilities to reason through online threats can leave them vulnerable. COPPA laws that protect children’s privacy extend to sites also interested in engaging children around health and money issues.

This brief overview suggests that the impacts of data security and sharing can be individual or family-wide, and can affect organizations and whole governments. Actions for safety thus fall in the personal, policy, and system levels. Because the issue of cybersecurity is so large, it is beyond the scope of this chapter or book to cover it in detail. Rather, we provide an overview of the various elements that comprise cybersecurity, their potential impacts, and the personal and regulatory steps that can be made. This is an ever-expanding topic as new forms of hacking (e.g., ransomware) and data chains are developed. Readers are encouraged to explore some of the sources in the Additional Resources section or do a search for information on topics of interest in this area.

Dimensions of online safety

There are four dimensions of safety online, as summarized by Commonsense Media:

- Safety: Protection of personal accounts and information from hackers and others to protect physical and emotional well-being.

- Privacy: Data is often collected to be used for marketing and targeting and personal sharing.

- Security: Protecting the integrity and confidentiality of a person’s data.

- Compliance: Adherence to existing laws and regulations.

Relatively recent data suggests that most Americans feel that their online data is not secure. A 2019 report by Pew indicated that 62% of those sampled reported that it is not possible to go through daily life without having their data collected by companies; 63% report this for government sites. What’s more, in most cases two-thirds or more are concerned with how the data is used and that the consequences of gathering the data outweigh the benefits, and more than half have little to no understanding of how the data is used, particularly by the government. There is a more generalized understanding of the commercial use of data to track interests and user demographics for the purpose of making life “easier.” (For those curious, the Pew report includes a section explaining data uses by the U.S. government.)

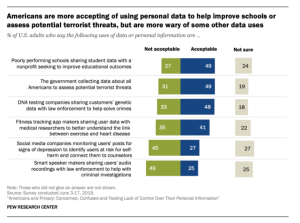

Yet although we are concerned, few of us object or don’t “agree” when asked when website popups solicit compliance about their data use policies. Likely, we are daunted by the long texts of legal information — in the Pew study, 63% say they understand little or nothing about laws to protect data privacy — or simply don’t want to take the time to read it all. And opinions are mixed when it comes to the purposes for identifying types of data. While many object when a social media site tracks posts about depression, few object that a school would sell information about poorly performing students to a nonprofit company that supports learning. This graphic from the report indicates views on a range of ways in which data is used. If you were part of the sample, would you find these topics of data sharing acceptable or unacceptable? If you’re not sure, what could help you know?

Identity theft

Identity theft is a specific privacy concern, and according to the 2019 Pew study, more than one quarter (28%) of Americans report experiencing one of three types of issues: fraudulent charges on a credit card, someone taking over their identity on social media, or someone trying to get a loan in their name. A student at the University of Minnesota related a harrowing experience with identity theft when a smartphone was stolen during a personal theft and assault. The assailants forced the individual to share the phone’s passcode and AppleID, which enabled access to a variety of apps. This included Venmo (discussed later in the chapter). Requests for money from members of the contact list, and charges on accounts available through apps on the phone, led to hundreds of dollars being stolen. More information on cybercrime can be found here.

Cyber safety

Digital applications and websites are subject to compliance with laws and regulations that fall into the general category of cyber safety. Cyber safety is a term for “the collective mechanisms and processes by which valuable information and services are protected from publication, tampering, or an assortment of unauthorized activities that are planned and implemented by untrustworthy individuals or unplanned events. Chapters 4 and 5 discussed safety online, particularly for individuals who are stalked as the result of using a dating app or for children who may be victims of cyberbullying. Privacy and security concerns include those discussed above, when a person’s data is shared for marketing or when data sharing breaches confidentiality. The COPPA laws intended to protect children’s privacy, discussed in Chapter 5, address some of these concerns.

Various laws are in place to protect security and privacy: https://privacy.commonsense.org/resource/evaluation-statutes. As this page explains, compliance includes regulatory, internal, and corporate compliance. Regulatory compliance is a site’s compliance with all available laws, rules, and regulations. HIPPA’s strict practices, in part, standardize health information and protect patient privacy, and penalties for non-compliance can include federal penalties and legal action. Internal compliance ensures that a site remains in compliance with federal and state laws.Industry compliance includes employee practices that safeguard data use.

Individuals and families can safeguard themselves when using the internet by being aware of the extent to which sites adhere to policies and regulations. Sites provide this information, though it can be buried and found only in links in small print. One superlative example from 1440.com; note how it explains what is collected, why, and how: https://join1440.com/privacy-policy/.

Data trends for 2022 indicate a variety of mechanisms to ensure web security (Marr, 2022). These can operate on large systems levels to protect against hacking breaches such as the Equifax incident, and can include practices for individuals to protect their data security. AI-powered cybersecurity, with its predictive ability to anticipate and monitor crime and threats from ransomware (which infects devices with a virus that locks files that will be destroyed without payment), leads companies to step up employee education efforts. This education warns employees not to open certain files or attachments, and to be aware of attacks on the Internet of Things (or those devices, such refrigerators and laundry machines in a house, that are connected to a network), cyberattacks in interconnected company data systems (the Forbes piece notes that “by 2025, 60% of organizations will use cybersecurity risk as a ‘primary determinant’ when choosing who to conduct business with”), and advancements on regulatory policies and practices.

Health Information and Care: Use of Technology in Personal and Family Health

The use of the internet and digital applications can have impacts on individuals — with indirect value to others in the family — and on whole families. With an estimated 39% of adults serving as caregivers, and with caregivers more likely to seek information about health online than other adults, societal interest in ICT and health extends beyond the individual. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of Americans used the internet to arrange vaccine appointments for themselves or another person (McClain et al., 2021). Reviews of technology used for individual and family health fall into the following categories:

- Web sites with health information.

- Social support and exchange of information on social media, discussion forums, YouTube channels, and more.

- Applications for the management of disease, as a complement to interventions, and for monitoring personal and family health.

- Wearable technologies for health data management, such as Fitbits and Apple Watches.

- Health care services delivered via technology (e.g., telemedicine) and the purchase of medical devices and pharmaceuticals.

- Robotic devices that provide emotional support and relieve stress in conditions such as dementia.

Reviews on individual conditions with clear family implications — such as dementia and eating disorders — provide useful information on the various ways that technology can be used to aid and assist (though sometimes challenge) health and recovery. As these are discussed below, consider how their use may impact the individual and have direct or indirect impacts on the family. Consider too what concerns may arise. For example, wearable technology collects massive amounts of data on individual health behavior and physiological conditions . This can inform health care practitioners in ways that mean more accurate reporting and diagnosis, but it can also mean data exposure and the need for protection from privacy violations (Cilliers, 2020). And while purchasing prescriptions online can be efficient and convenient for those homebound or in rural areas, recent reviews of online drug providers finds that consumers show be wary. Providers were found to pair drugs with services not designed for long-term support, or to enhance prices to capitalize on convenience.

Information about health online

For better or worse, the internet has become a significant source of information about health, illness, disease prevention, and recovery. Prior to the availability of the internet, individuals sought out health practitioners for information, turned to trusted others (e.g., family or friends), or sought written materials or audiovisual media in libraries. With the availability of information online, individuals can access a wide range of sources, compare facts, tailor the information to their specific interests, and determine whether to seek medical care or treatment at home. While there may be consequences, informed patients may take greater agency in their health management. Tan and Goodawardene (2017) observe possible consequences of the change. These include exposure to information that is of questionable quality, requiring, as will be discussed later in the chapter, a critical eye in discerning accuracy and usefulness. Patients may be misinformed and incorrectly self-diagnosed, which might keep them from visiting the doctor. Some may feel less satisfied and less trusting of the physician, which may even lead to arguments and conflict. Yet the review of the literature did not indicate weaker relationships between patient and doctor due to the availability of health information online. Indeed, they found that more informed patients may ask doctors more questions and take greater agency in their health care and management.

Social support and information exchange

The ability to learn about health conditions from others’ personal experiences is a major advantage of the internet. Early research on families and health online came from the mental health community, when parents of children with mental disabilities exchanged information through discussion forums (Scharer, 2005 ). Significant research has since explored the emotional and informational support benefits of these exchanges as parents, caregivers and individuals find others who share similar experiences, though they may not be known personally or have access in real life. From discussion forums to social media pages, to health and mental health care advocates, to condition-specific applications, ICT has expanded reach to information, and enabled personal relationships and connections for direct support.

Applications for caregivers of those with dementia have demonstrated particular value. Shu and Woo’s 2021 review of the literature indicates that people use the internet to diagnosis dementia. In-home technologies serve to support seniors living alone and offer support to caregivers of dementia patients, and social media and YouTube offer education on dementia that is valuable to patients and caregivers alike. Yet research suggests that internet use by the elderly greatly depends on the perception of value, comfort, and skill in using social media for learning.

Online groups have also been identified as valuable for patients with eating disorders (Howard, nd), providing valuable peer-to-peer support for positive recovery and emotional encouragement. And in some cases, hard-to-diagnose diseases have been addressed through facilitators like Dr. Lisa Sanders’ column Diagnosis in the New York Times and dramatized on Netflix.

While the internet has expanded access to information about an illness such as cancer (VanEenbergen et al., 2020) or schizophrenia (Hswen et al., 2020), or about a medical condition one is attempting to prevent (e.g., diabetes, Sauder et al., 2021), concerns have been raised about the potential for false information that might lead to mistreatment of the condition, exacerbation of symptoms, mental health consequences, or worse. Many online influencers and groups are neither sponsored by a medical or health care agency nor facilitated by a professional. While discussion of treatment modalities and new research is positive for learning, moderation can help the conversation stay positive and constructive for all involved.

One example of how social media can influence health information is a study of children’s perception of the dangers of nicotine, examining children’s exposure to the e-cigarette “Puff bar” through 148 TikTok videos in 2020 (Morales et al., 2022). The videos had been collectively viewed over 137 million times. A 2020 study examined children’s exposure to e-cigarettes through TikTok videos. Researchers identified viewer apathy to the effects of nicotine through repeated exposure. Instead tobacco-related content was associated with positive attitudes and intentions. Elements of content regarding the cigarettes included skits and stories, shared vaping experiences, product reviews, and promotions and crafts. The researchers identified viewer apathy to the effects of nicotine with repeated exposure to the content. They noted that, “For adolescents, more time spent on social media is associated with greater intention to use e-cigarettes, and exposure to and engagement with tobacco-related content have been associated with positive attitudes, norm perceptions, and intentions.”

Self-authored blogs, social media pages, and video channels are also ways that individuals share and consume health information. For many, these offer deeply personal mechanisms for sharing and taking part in others’ experiences. For example, the Clarity Project [1] was a YouTube channel offered by Claire Wineland. She was a teenager who had cystic fibrosis, and her videos shared her daily experiences of living with the disease. Sadly, she passed away in 2018 during recovery from a lung transplant. Before her death, she had amassed tens of thousands of followers and become an advocate for those living with a chronic medical condition. Here’s a sample video journal:

Health care management

Apps and other technology that detect falls or gas and carbon monoxide leaks can reduce concerns for persons with dementia. Other apps can track medication use and offer reminders to aid compliance. Recovery apps for illnesses such as alcoholism or eating disorders offer mood check-ins, mindfulness tips, constructive monitoring of eating and exercise, and ways to identify triggers.

Readers may be interested in seeing the details of this clinical trial for an app that aids those with anorexia nervosa after intervention. As there is a significant rate of relapse, the app is intended to optimize clinical service done face-to-face and improve treatment response. The web page includes descriptions of measures used by the researchers to assess use and usefulness of the app, and clinical details of the patient’s condition, thus pairing technology use with the condition it seeks to aid.

Yet such health management apps appear to be primarily focused on the individual, not those providing assistance and support. Grossman and co-authors (2018) acknowledge that of the hundreds of thousands of medical apps available, few address caregiver needs. Only 18%, for example, offered stress reduction activities for caregivers.

Wearable technologies

Wearable technologies provide ways to monitor body response and can send information to health care practitioners. Fitbits and similar products can also be used by individuals with dementia (Shu & Woo, 2021), providing fall detection and information on sleep, physical activity, heart rate, and arrhythmia that can guide physicians in care plans.

Although research is limited on the effectiveness of activity trackers and wearable technologies for full family health, there are positive indications. This Australian study by Shoeppe et al. (2020) tested physical activity gains in the family after each member wore a fitness device for 12 weeks. In this study, the whole family included both parents and at least one child age 9–13. In addition to fitness trackers, family members also used a tailored app to align with the device, information on recommended activities, and a motivational poster, and received motivational texts up to three times per week. Measuring outcome by the number of steps, all family members showed significant gains. The researchers focused on the value of family dynamics (e.g., parental role modeling, consistent communication) and reciprocal motivation (e.g., family members acting as agents of change) as likely influences on family member success. Although the study is limited by the number of participants and the lack of a control group, the authors suggest that it indicates promise for whole family health. These devices, however, are also subject to data breaches (Cilliers, 2020).

Telemedicine

As this piece in Everyday Health indicates, the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) defines telemedicine as “the practice of using technology to deliver medical care at a distance, over a telecommunications infrastructure, between a patient at an originating site and a physician or other licensed practitioner at another site.” This is different from telehealth, discussed above, which includes the use of “electronic and telecommunications technologies that support a variety of remote healthcare services, such as medical, health coaching, and education services.”

As would be expected, the use of telemedicine rose during the COVID-19 pandemic. When physicians’ offices were used to treat individuals with the virus and stay-at-home orders kept families inside, one’s home became a preferred location for the delivery of care. Seivert and Badowsk i (2020) indicate the benefits of telemedicine to the individual, the provider, and the health care system. Individual benefits include access to medical professionals beyond traditional hours, cost savings, and travel reduction. For professionals, benefits include travel and cost efficiencies, care provided to hard-to-reach areas, such as rural territories, and increased practitioner satisfaction. For health care systems, telemedicine offers the ability to expand service beyond time and place boundaries, decrease staff burnout, and reach underserved populations. Additional benefits enable professionals to provide caregiver support, and monitor patient vital signs and compliance.

Yet there are barriers and drawbacks to telemedicine. Staff members need training to deploy telemedicine effectively and ethically. Some individuals/patients are concerned with privacy or interruptions by others, may be challenged with access to the internet or in comfort with using a range of applications, or are less comfortable talking over the internet. When others are nearby, some individuals may feel reluctant to talk about health or mental health concerns.

Robotic devices

One avenue with promise for health care, particularly for those living with dementia, is robotic products. As indicated in the table in this article (Shu & Woo, 2021) robots can be fashioned as animals (e.g., otter, seal) or humanoids, and holding the robot can offer relief from the neurological symptoms and distress of dementia and provide emotional support. These are excellent alternatives when animals are not allowed in medical facilities or there are concerns with allergies. Robotic devices are also used in training health care providers. For example, this video features a robot patient needing a Cesarean section. As you watch, how do you think robots might be beneficial to practitioners in training? Can you imagine any negatives ? Shu and Woo conclude that, while there is promise in robotic devices for family member health care, particularly for those with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, knowledge and assessment tools are as yet unavailable to evaluate specific device use for specific needs. As with other technologies — and as the thread through this book holds — consumers and family members must become knowledgeable enough to make individualized decisions based on personal goals and needs.

Health e-literacy

With the overwhelming number of websites that share health information, plus the exchange of information through social media and from person to person via apps such as WhatsApp, it is up to individuals to determine whether information is safe and useful. Personal health literacy, as defined by the US Department of Health and Human Services is, “the degree to which individuals have the ability to find, understand, and use information and services to inform health-related decisions and actions for themselves and others.”

Evaluating health information online

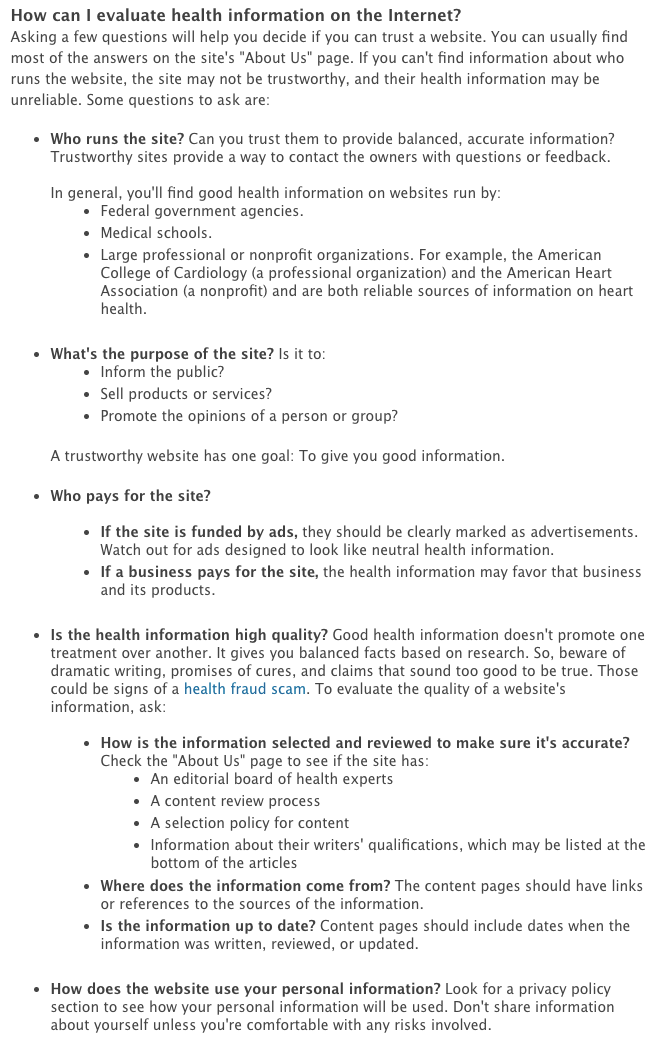

A helpful acronym USE:

U: is the site easy to use (e.g., to navigate, read, understand?

- Is it an app or device? Or interactive software? Does it do what is it supposed to?

- Are the tools and resources easily readable? In the language needed? With ability accommodations?

- Does it work with other devices or platforms?

S: is it safe? Does it feel secure? Private?

- Is it secure? Does it track your data? How can you tell?

E: is it effective? Does the information provided seem like it’s coming from a reputable source? Is the information reasonable to your situation?

- Is it up to date?

- Who provides the information?

- Is the information accurate?

Another health information source from the U.S. government, Medline, offers constructive questions that broadly explore source and quality:

Organizational health literacy puts the responsibility on organizations to enable individuals to find and use information for health-related decisions.

Health information through social media

For some, it may be more challenging to determine the accuracy and usefulness of information passed along within a personal social network, including “friends” on Facebook, those followed on Instagram, and TikTok. This video by John Oliver on HBO examines Whats App and the spread of misinformation about COVID-19 and immunizations, especially among family members: As the video indicates, information spread through immigrant communities, with little oversight by the app companies or the government to regulate the sharing of potentially harmful information. A 2021 review of the pre-COVID literature about health misinformation in social media (e.g., up to 2019) by Suarez-Lido and Alvarez-Galvez identified that Twitter was the predominant platform, with the research identifying the following topics (in order of dominance): vaccines, drugs or smoking, noncommunicable diseases, pandemics, eating disorders, and medical treatments. Medline suggests that social media users follow similar questions about the accuracy of health information online, and, when in doubt, that they don’t share the information.

Assessing individual health e-literacy

A number of tools are available to help assess an individual’s e-health literacy; indeed, a recent search identified more than 200 measures. A resource for identifying tools is at https://healthliteracy.bu.edu/. Health literacy domains of competence range from communication, comprehension, and content knowledge to information-seeking skills and numeracy. Many measures offer Likert scales (e.g., strongly disagree to strongly agree), giving a quantitative number to items that can be summed, averaged, and viewed by subcomponents. Sample items may include:

- I have the skills I need to evaluate the health resources I find on the Internet,

- I can tell high-quality health resources from low-quality health resources on the Internet, and

- I feel confident in using information from the Internet to make health decisions.

One example measure is the All Aspects of Health Literacy Scale (AAHLS ), which has 16 items, measures application/function, and takes about 7 minutes to complete. For professionals designing sites (discussed in more detail in the upcoming chapter on family professional application of technology in practice), this health.gov site provides a useful checklist.

Financial e-literacy and U$e of Technology for Family Financial Well-being

As technology has made our families more accessible, efficient, and even healthier, it has also contributed to our ability to manage money and be financially healthy. Think of the many ways in which technology figures into your financial life, and consider how things may have changed with COVID-19. With e-commerce, digital advisory services, e-banking and investing cryptocurrencies, and personal financial management (PFM) technology (all within the category of fintech) enabling access and exchange without leaving the house, we marvel at the efficiencies in how we shop, earn, spend, and learn about money (and, in the case of families, teach children about money management ).

Yet, just as with health-related devices and networked information, using the internet and apps for our money can also expose us in ways that can have serious consequences to our identities, sense of safety and security, and privacy. And as our use of technology has permeated our everyday life, it has become an item in our budgets. As we begin this section, consider your own use of technology to manage your finances and spending. Do you use an app to track financial accounts and perform banking? An app to help stick to a budget, or to make online purchases? Do you go online or use an app to gather information about products and financial matters? Do you communicate with a financial professional through an app or online?

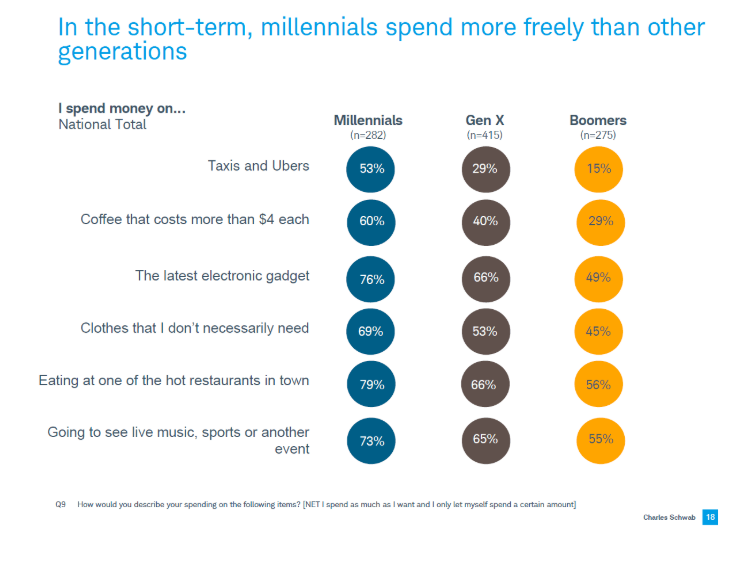

In the Families and Technology course, most students report using an app to track their finances or make purchases. Far fewer maintain a budget, communicate with a professional, or seek information online. Consider your parents or grandparents. Is their behavior using financial apps (or “fintech”) different from yours? Research suggests that there are clear age trends in online/tech-aided spending and shopping. Younger generations (e.g., Millennials, Gen Z-ers) are more likely to use digital technologies, and their spending is different as well. As indicated in this graphic from a report by the Medium, Millennials are more likely to spend on events, experiences, and efficiencies than Gen Xers and Baby Boomers.

As Lombardo in The Medium observes, “It’s not that Millennials care any less about appearing more successful than previous generations, it’s that the definition of success has changed. Whereas yesterday it was measured in things, today it’s measured in experiences.”

Of the population born after 1996, Emily Pribanic says “Generation Z is a bunch of tech-savvy savers who have all the information and resources they need at their fingertips.” Compared with Millennials, Gen Z is less likely to rack up student debt or carry a mortgage, and are more likely to save. They embrace technology for person-to-person money transfers (like Venmo or PayPal) and are active information seekers in making sound financial decisions. The tech-savvy nature of the generation — assured to have grown up with ICT — will demand that banking is mobile, systems are cashless, and apps make financial management efficient.

Use of technology and money management

The growth of fintech, including personal financial management (PFM) technology, has gathered researchers’ interest about use, differences in use, and impact. Millennials (those born between 1980 and 1996), for example, have been studied for how their use of PFM takes the place of more traditional methods (e.g., going to an ATM). PFM includes applications that focus on budgeting (like Mint), credit score monitoring, and personal informatics, used to review balances and overdrafts and to make behavioral corrections to stay financially balanced. It’s acknowledged that Millennials have their share of financial considerations, paying off student loans, acquiring stable jobs and income, paying rent (or returning to live with their parents), and saving for retirement. And many don’t feel knowledgeable about how to manage their money [2].

Walsh and Lim (2020) indicated that PFM use led to fewer fees and penalties and better transparency, which led to more efficient borrowing. Compared with older individuals, Millennials are more likely to use PFM and be considered moderate or heavy users (Walsh & Lim, 2020). Using the Technology Acceptance Model (Davis, 1989), which considers use related to perceived benefit and ease of use, the authors found a relationship with financial pressures, interpreted as the perceived value of using PFM. Heavy adopters’ involvement in “side hustles” or working as Uber drivers and similar jobs dependent on technology, offered comfort with using digital applications; the authors interpreted this as “perceived ease of use.” And yet heavy adopters were also more likely to experience debt, so the authors indicated that PFM use didn’t translate automatically to financial knowledge or skill. Overall, they point to the need to include PFM in a system of financial education and management for Millennials, rather than see it as the mechanism for change.

Cryptocurrency

As Ladrum notes, Millennials have demonstrated their industry by creating an alternative currency. Investopedia defines cryptocurrency as:

a digital or virtual currency that is secured by cryptography, which makes it nearly impossible to counterfeit or double-spend. Many cryptocurrencies are decentralized networks based on blockchain technology — a distributed ledger enforced by a disparate network of computers. A defining feature of cryptocurrencies is that they are generally not issued by any central authority, rendering them theoretically immune to government interference or manipulation.

Recent research by the Federal Reserve suggests that 12% of American adults use cryptocurrency (O’Sullivan, 2022 ). In a 2022 report from T. Rowe Price, 28% of their sample of U.S. adults included cryptocurrency in their investment portfolio. The Federal Reserve report indicates that most of those who use bitcoin (one type of cryptocurrency) do so as an investment; these users tend to have more education and income. A smaller percentage uses it for transactions; these users tend to have less education and income and to be “unbanked” (not having a bank account). It is valuable to keep an open mind and flexible attitude as we learn more about cryptocurrency and its value, particularly given its recent entry into the financial market and for use by families. A 2022 report on families and money by T. Rowe Price (2022) indicates that children are interested in cryptocurrency, and that those 11–14 years old are more familiar with it than their parents (57% vs. 47% of adults). As Hernandez (2019) writes, there is flexibility with bitcoin and the like that can protect it from the influences of government economies, such as that experienced in Venezuela when inflation affected the value of currency and consumers’ ability to purchase or earn money.

Use of technology and a cashless lifestyle

Fintech has also revolutionized the ways families spend and share money. We are moving towards a cashless society and relying more on online shopping and delivery services for our groceries and household needs. We exchange money with others without it touching our hands. The shopping experience has radically changed. Age trends in online/tech-aided spending and shopping suggest generational differences in the likelihood of using digital technologies in shopping.

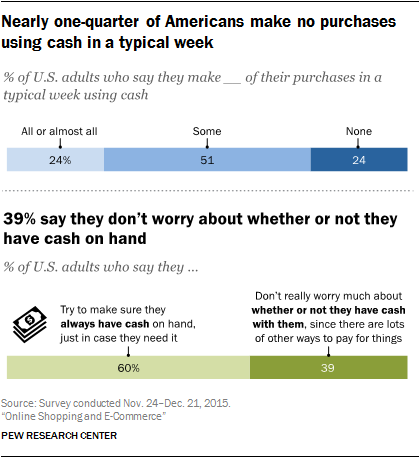

How many purchases do you make during a week using cash? When Pew asked this question in a 2015 survey, 24% of the respondents said none, while half (51%) said some. Each semester this question is put to students in the Family and Technology course. In the spring of 2021, 56% of students said none. While the composition of the sample in the Pew study didn’t match those of an undergraduate course, we still see the pattern of change over five or so years, with an increasing number of people reporting that they never use cash.

Paying without cash is certainly not a recent innovation. Credit for purchase transactions dates back hundreds of years, and electronic credit cards were introduced in the 1960s. Decades of credit card use allow research on consumer behavior, and research shows that not using physical cash for transactions (“friction-free spending”) leads to overspending (Schwartz, 2016). ApplePay was introduced in 2014, enabling consumers to load bank information on their phones and make purchases without using a physical credit card.

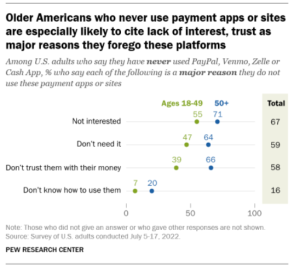

Use of money-sharing applications like Venmo, Zelle, and CashApp is also growing. Research from Pew in 2022 indicates that about 57% of Americans use PayPal, while approximately 1/4 to 1/3 use other apps. There are clearly demographic differences in use, with older adults less likely to find them necessary, safe, or easy to use, as seen in the figure (Anderson, 2022).

The future of purchasing may include biometrics such as fingerprint sensors. As research develops on these newer forms of a cashless lifestyle, experts believe that the temptation for overspending will only increase.

Online shopping

How often do you shop online? Have your online shopping patterns changed since COVID-19? In 2015, research by Pew indicated that 79% of people shopped online, with 15% saying they shopped online weekly. Greater frequencies were reported for less frequent shopping: 28% said a couple of times a month, 37% said about once a month, and 20% reported never shopping online. In recent years, however, shopping online has become more popular, particularly as more shoppers come from younger generations who are more tech-savvy (e.g., GenZ). During COVID-19, 32% of adults purchased food online from a restaurant, with those age 18–23 years reporting the greatest frequency (53%; Vogels, 2020). Shopping online is apparently driven by hedonistic, normative, and utilitarian motivations (Koch et al., 2020), and during COVID-19, hedonistic motivations for online shopping increased (Koch et al., 2020). This isn’t terribly surprising, given the isolation and lack of social contact that occurred during the pandemic.

In the near future, more than half of retail sales will be from online purchases (Balls, 2019). This can mean the closing of small establishments, with impacts on investors in brick-and-mortar businesses, on workers, and on land values.It is estimated that Amazon netted $18B in sales in 2021 (and didn’t pay taxes). Other online retailers reported increases, and brick-and-mortar stores escalated their online sales. Delivery services like DoorDash have also become popular, and small businesses have found success selling through online brokers like Etsy. Yet Balls (2019) observes the downsides to e-commerce, and finds it unsustainable in the long run. He reports that, in the near future, more than half of retail sales will be from online purchases. This can mean the closing of small establishments, with impacts on investors in brick-and-mortar businesses, on workers, and on land values. Balls estimates that delivery costs will increase or be passed along through wage and benefits cuts to drivers, and that additional vans for delivery will negatively impact the environment through carbon emissions. And then, of course, the more business we give to online sellers, the more sharing there is of our personal data and our credit card and bank information.

Technology as a financial consideration in household spending

Household spending estimates frequently don’t include technology costs. This article, written as late as 2021, includes a range of household items, and technology isn’t mentioned, even under “miscellaneous.” This is surprising given our use of personal computers in the 1980s, the introduction of peripherals for those devices, and then the advent of cell phones, smartphones, and wireless technologies in the new millennium. National surveyors have taken notice of the ways in which overall household budgets have been consumed by technology purchases. Consider these categories:

- Internet services and equipment, such as routers.

- Smartphones: devices, calls, content, services, apps..

- Consumer electronics: TVs, game consoles, GPS, paid TV/streaming services, movies.

- Printers: ink, toner, paper.

- Personal computers: laptops, desktops, hardware and software, installation, warranty.

- Handhelds: ebook readers, tablets, smartwatches, fitness trackers, cameras.

- Peripherals: headphones, flash drives, external hard drives, HDMI cables, chargers, cases.

How much do you spend per month and per year on these items? Consider what you’d pay for those items you may get free, perhaps from what someone else pays for (e.g., wifi covered by the University for your dormitory and classrooms) or for what you “bootleg” (e.g., your parents’ Hulu account). A Learning Activity for this chapter encourages you to keep track of your technology expenses. They can add up, and be a significant portion of your budget. According to Pew, (McClain et al., 2021), nearly half of broadband users in low-income households say they worry some or a lot about being able to pay for their high-speed internet. Not surprisingly, those with higher incomes worry less.

Financial e-literacy

As with learning about health, digital apps and online resources are valuable for gaining and exchanging financial knowledge and skills. For example, a study by Moor and Kanji (2019) explored women’s conversations about money on an online site called Mumsnet. They determined that women use the discussion to clarify social norms about money and relationships, to develop communication skills specific to money through interacting with other women online, and to learn about resource allocation. As discussions about money are a key challenge in many marriages and relationships, finding support from others on how to communicate within a relationship is incredibly valuable.

Yet, as with health information, families need to be wary about the accuracy of information about spending, saving, and investing shared by those online. Social media influencers, bloggers, and web-based scams can promote information that is misleading and possibly dangerous. One recommendation is to ask — again, as one might with health information — who is the source? Is the information credible? Resources such as factcheck.org can be useful as well.

Teaching children about money

Children learn how to manage, spend, and save money through modeling and direct lessons from their parents (Serido & Deenanath, 2016; Yeung et al., 2002). A recent report by T. Rowe Price (2022) indicates that parents are the dominant source of trusted information about money; social media ranks second, with 40% of children 11–14 reporting this source.

Experts recommend that parents instill a habit of saving, create opportunities to earn money, help children make smart financial decisions, show them the value of giving, and guide them in the ways their money can grow (Huddleston, 2020). As with other behaviors, a parent’s own financial literacy is greatly shaped by experience, culture, and context, and personal perceptions about money (Britt, 2016). And as Chowdry (2019) observes, generational differences in experiences and perceptions of how money is used and understood relative to the digital world can be barriers to parents’ choosing and interacting with their children around technology. Yet children are developmentally capable of learning about the basics of savings at a relatively young age (e.g., 5 years). And while families vary greatly in the ways in which they teach children about money (Britt, 2016; Morris, 2021; Serido & Deenanath, 2017), new fintech tools offer promising mechanisms for a cashless, virtual financial world.

Credit/debit cards for children

“Smart” debit cards are attached to an app that allows parents to control the amount of money in the account, and children can use a physical card to make purchases. This makes it easier for parents and children to monitor the amount of money spent, and removes the need for small amounts of cash. For example, if a parent gives their child money for a chore or a weekly allowance, the smart card can be filled. Some apps are designed to be interactive and enable children to dictate different uses of the money, under the traditional save/spend/share. Apps may be designed around doing chores, setting time or date goals for earning and saving, and vary by level of parental control. Scholars appear positive about the use of these applications, as they represent the worlds that children are growing up in and toward, though some raise concerns that app-to-app communication removes the personal interaction that is meaningful for family communication and deeper learning (Carrns, 2018, NYT).

Apps and interactive sites to teach children about money

Financial experts recommend that parents find useful apps and online sites to help facilitate financial literacy (Morris, 2021). Sites like The Mint (themint.org) and Practical Money Skills (practicalmoneyskills.org) offer games for learning about saving, spending, earning, and giving, along with quizzes and calculator tools (Keeley, 2022), while Biz Kids (bizkids.com; bizkids.com [YouTube]) is a TV series featuring teenagers. In usability, learning, and content presentation, the sites consider the age of the child (the Mint, for example, offers information for children, teens, and young adults) and includes other audiences (parents and professionals; Chowdry, 2019). They are often available on platforms and with operating systems that complement the range of devices used, and may be available in languages other than English. According to their website, Practical Money Skills is available in 19 languages and 46 countries.

This chapter closes out our journey through the use of technology (ICT) by families, and what research to date suggests as impacts of use (many impacts beyond the consumer), and the myriad variables that influence those impacts. We now shift gears to examine the professionals who put this knowledge into their practice in their work with families: therapists, social workers, family educators, and more. We’ll discover that more than a body of content knowledge, technology are tools for practice. And the great divide among practitioners may exist in access to those tools and in the knowledge and comfort in using them effectively.

- View a documentary about Claire's advocacy, and see videos from her channel. ↵

- See, for example, this Forbes article and G Washington study. ↵