Chapter 6: Technology Use by Parents

Be strong, be fearless, be beautiful. And believe that anything is possible when you have the right people there to support you.

– Misty Copeland

Chapter Insights

- Although research on adult technology use exists, an interest in parent use requires specific study.

- This chapter identifies three main ways that parents use technology to serve their parenting roles: using technology to parent, using technology with children, using technology to support oneself in the parenting role.

- Parents vary in their technology use. These differences are important to keep in mind when exploring parents’ impact on children’s development in terms of technology use and oversight.

- Five domains of parenting practice integrate ways in which technology is used by parents, and can be used to measure successful parenting.

- Generational differences play out in a parents’ use of technology.

- Parents are not necessarily “equal” when it comes to using technology on their own, and in fulfilling their parenting role.

- “Sharenting” can be useful to reinforce the childrearing experience, yet can also bridge ethical challenges to children’s privacy.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

Introduction

Every day, and for many all day, adults use ICT in many different ways. But consider what they use in their roles as parents, how technology relates to or facilitates those roles, who it’s used with, and what parenting goal results. How do your parents or other caregivers you know use technology to fulfill their roles in parenting?

In the previous chapter we examined technology use by children from birth through young adulthood, exploring potential impacts on their development and well-being. We discussed the benefits and potential consequences of technology use across ages and developmental domains, all of which are the focus of ongoing research. Embedded and implied in the discussion were parents’ roles; their concerns around the amount of time children are on screen, their responsibilities for healthy engagement, and family decision making about children’s responsible smartphone use. Lim (2016) calls this the practice of “transcendent parenting,” which goes beyond traditional, physical concepts of parenting to incorporate virtual and online parenting.

Recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatric about technology use by young children, older children, and teens (Pathway Pediatrics, 2021) are written almost exclusively to parents — underscoring how our society confers on parents childrearing responsibilities that include technology management skills and the knowledge of technology’s impacts.

Parents integrate technology into their parenting — using phone calls, texts, social media interactions, and other experiences as ways to convey guidance and nurturance to children. Consider how your parent(s) communicate with you. What parenting messages or roles are conveyed through these methods? Parents also use technology in ways that support them as parents and only indirectly impact children.

|

|

|

Chapter 7 will explore relationship dynamics between parents and children when parents assert their parenting role around children’s safe and healthy technology use, and children assert agency in use. This includes parents’ mediating, moderating, and monitoring children’s use (parenting about technology), and impacts on the parent-child relationships. Chapter 7 will also include the ways in which parents use technology with their children to convey words and actions. In this chapter, the focus is on parents alone — how parents themselves use information and communications technology, and the value and purpose it serves in parenting and to the parent him or herself.

Here are a couple things to keep in mind as we go through this chapter:

- Data reporting “adult” technology use is not sufficient to capture the role of parenting by adults. It is important to distinguish research focused on parents from that focused on the childrearing role fulfilled by parents. As an example, Duggan et al. (2015) focused on social media and internet use among parents and non-parents, though the study included a representative sample of U.S. adults. They showed that parents are more likely to use the internet than non-parenting adults and that they use types of social media differently (participating in most social media applications, except for Instagram, in greater numbers). Some research on adults may report the data as coming from parents, under the supposition that those who are parents are adults, yet discrimination is necessary for accuracy. Fortunately, as parenting researchers became more comfortable doing studies that involved technology and internet use, the availability of studies collecting and reporting results from parents is more available.

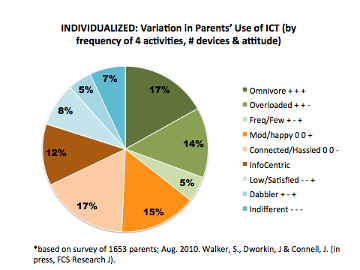

- Parents are not monolithic. They vary by age, maturity, gender, family configuration, number of children, culture, race, global location, and much more. In Chapter 3 we discussed how these variables can influence differences in family technology use. Like other technology users, parents vary widely in their access, use, function, and attitude about devices. More than a decade ago, the author’s research on parents and technology use identified how caregivers vary by their attitudes toward technology mixed with device ownership and activity (Walker et al., 2015). Over 1,600 parents of children under the age of 18 were surveyed online. We asked questions with regard to the frequency of their doing four different activities with technology such as communication and information searching, the number of devices owned in the household, and their attitudes regarding technology. As you can see in the chart below, we identified nine different groups. “Omnivores,” or those in families with many devices doing all kinds of activities, held a very positive attitude about technology. The majority were in the moderate category, where they may have used technology for very specific purposes, had an average number of devices ,and may have had very positive or not-so-positive attitudes with regard to technology.

A smaller group (likely even smaller now) were indifferent/had a few devices/had fairly negative attitudes about technology and used them for few activities. Certainly, over time and with new devices and applications and ICT functionality, even more differences among parents can be seen. The essential issue is that we don’t hold a belief that parents use technology in the same ways.

A smaller group (likely even smaller now) were indifferent/had a few devices/had fairly negative attitudes about technology and used them for few activities. Certainly, over time and with new devices and applications and ICT functionality, even more differences among parents can be seen. The essential issue is that we don’t hold a belief that parents use technology in the same ways.

Many caregivers are employed, and the conditions of their workplaces and jobs vary widely. These contexts affect technology use, access, and comfort in ways that affect parents as employees and their parenting and presence as parents. Being available for calls or meetings in the home space and during nontraditional hours can distract parents from being attentive to children. In other cases, parents who appreciate the flexibility provided by mobile technology and home internet may juggle responsibilities and be more available to children.

Jointly, these demographic characteristics influence parents’ needs on what to know about technology and what they may do with it, and they play a role in their comfort with ICT. Too often, discussions generalize “parents’ social media use” or “parents” monitoring of their children’s use, when in fact wide variation exists among parents. Pew’s study of parent social media use, for example, shows vast differences between mothers and fathers in types of social media, purposes for use, and frequency of behavior (Duggan et al., 2015). Yet a global statement referring to “parents” lacks discrimination by gendered role.

Before diving into specifics of parents’ technology use, we begin with an overview of the parenting role and influences on it. This framework provides a foundation for understanding technology use as expression of the parenting role.

About Parenting

Parents represent one of the largest and most significantly important population groups in any society. In essence, they are directly (and legally) responsible for raising the next generation of adults, and the quality of their efforts is related to developmental and educational outcomes. Economically, their earning power to support their children, their tax contributions, and their consumer behavior contribute greatly to society’s wealth and resources. Yet individuals receive no formal training for parenthood, and with economic challenges and shifting family structures leaving many parents alone in childrearing, and with a lack of public services in the U.S. for all but the neediest families, parenting is highly challenging. In fact, most parents say that parenting today is far tougher than when they were growing up (Auxier et al., 2020).

Parents represent one of the largest and most significantly important population groups in any society. In essence, they are directly (and legally) responsible for raising the next generation of adults, and the quality of their efforts is related to developmental and educational outcomes. Economically, their earning power to support their children, their tax contributions, and their consumer behavior contribute greatly to society’s wealth and resources. Yet individuals receive no formal training for parenthood, and with economic challenges and shifting family structures leaving many parents alone in childrearing, and with a lack of public services in the U.S. for all but the neediest families, parenting is highly challenging. In fact, most parents say that parenting today is far tougher than when they were growing up (Auxier et al., 2020).

To understand the ways in which technology aligns with the parenting role is to first understand what “parenting” is, and then to identify the multiple influences on parenting. These can help us imagine the various ways that technology helps to fulfill the parenting role and factors that might differentiate its impacts.

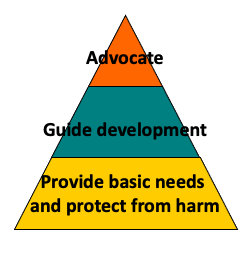

At its most basic, parenting can be conceptualized hierarchically to mean keeping children protected, healthy, and surviving (most basic function); nurturing, and guiding their development (where most of our traditional notions of parenting lie); and, when needed advocating on their behalf. [1]

For most parents, the first level — providing basic needs and protecting from harm — is a given, yet for many families it’s truly an economic struggle. Our social welfare system is in place to assist families with meeting basic needs, especially around housing, health care, nutrition and finding employment. The second level, guiding development, is a process that doesn’t stop when children are 18 or out of the house. Throughout a child’s life, they will seek and be guided by their parents. Actions that parents take in guiding children, as described in a booklet by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, include responding in an appropriate manner, monitoring to preventing risky behavior or problems before they arise, mentoring to support and encourage desired behaviors, and modeling their own behavior to provide a consistent positive example for the child. The third level, advocacy, is expressed in big and small ways, also throughout a child’s life. It may be individualized, such as when a parent meets with a teacher on behalf of one child, or globalized, as when a parent advocates for an issue that affects many children, such as lobbying for children’s technology privacy and safety. Think about your own life, and how your parent or parents have fulfilled these roles for you.

Parenting is often thought of in a directional way, with parenting action “causing” child outcomes (For example, the news reports of teenager committing crime and someone remarks about ‘bad’ parenting.). Perhaps this is because of the authority conferred on the responsibility of parenting, across the child’s early to later adolescent years and beyond, and the enactment of these responsibilities to help children flourish. Dynamics of family roles, certain experiences in families, and the way parents are often represented in the media can suggest that parenting actions directly impact the child. [2]

Impacts on child development are, however, mulitfactorial. And parenting is a bi-directional and a transactional process. A parent attends to the needs of the individual child and tailors their responses to that child’s individuality. They reflect on their resources, gain understanding from the interaction and observation with the child and in the context, and learn. This is attunement. Once again, consider your brothers and sisters if you have them: did your parents parent them the same way as they parented you? Probably not. Your brothers and sisters are different than you, they are different ages, possibly different genders, and have different personalities and temperaments, and your parent was a different age when each sibling arrived. Your oldest brother/sister may have been born when your parents were in their twenties, and by the time you came along your parents were ten years older. You can imagine how much experience they had gained in those ten years. So as parents understand and react and respond and guide their children, they too grow and develop through their experiences as human beings, and they attune and transactionally gear their childrearing based on information they glean through interaction with the child.

Although there are many frameworks of parenting, ones that incorporate individual differences of parents and myriad contextual factors as influential on parenting and parent-child relationships are useful to apply cross-culturally and when viewing parenting in the novel area of technology. Most social systems perspectives of parenting emanate from a bioecological paradigm (Bronfenbrenner, 1995), discussed in Chapters 2 and 5. frameworks of parenting that incorporate individual differences of parents and myriad contextual factors as influential on parenting and parent-child relationships are useful to apply cross-culturally and when viewing parenting in the novel area of technologyThis perspective recognizes individual behavior and growth as influenced by interacting systems, sensitive to change and to time, in which the individual is variably affected, largely related to qualities unique to the individual and to proximal processes or ‘‘enduring forms of interaction in the immediate environment’’ (p. 620). A social constructivist view of development (Vygotsky, 1978) supports the role of the context in scaffolding parent development to move to a higher level of functioning, provided that they are in their “zone of proximal development” (within their developmental reach based on existing capacities). Adequate contextual supports can help adults acquire a greater repertoire of cognitive, behavioral, and relational skills, and reinforce identification in the role. The social context can, however, interfere with growth, or may assert needs that are beyond the individual’s capacity (e.g., living in poverty). A competency model proposed by Johnson et al. (2014).[3] adds to the rudimentary model above by adding to functional competences (e.g., provision of basic needs, behavioral guidance), with foundational competencies (e.g., psychological health) and contexts (child age, development, parental social network).

With consideration to the focus on technology, children’s technology use and individual differences of the child can be seen as context factors, as can influences from school and peers and wider institutions on that use. These intersect with foundational elements of the parent’s own psychological and cognitive abilities and attitudes to influence apparent parenting behaviors related to technology use (their own, the child’s, and the family’s). This model also reveals child use or parenting response not as a linear action, but as interactive and recursive in response to other elements. Parenting behavioral guidance will change with the child’s age, and a parents’ mental health may improve with feelings of self-efficacy as a result of interactions with their child around technology use.

Influences on Parenting

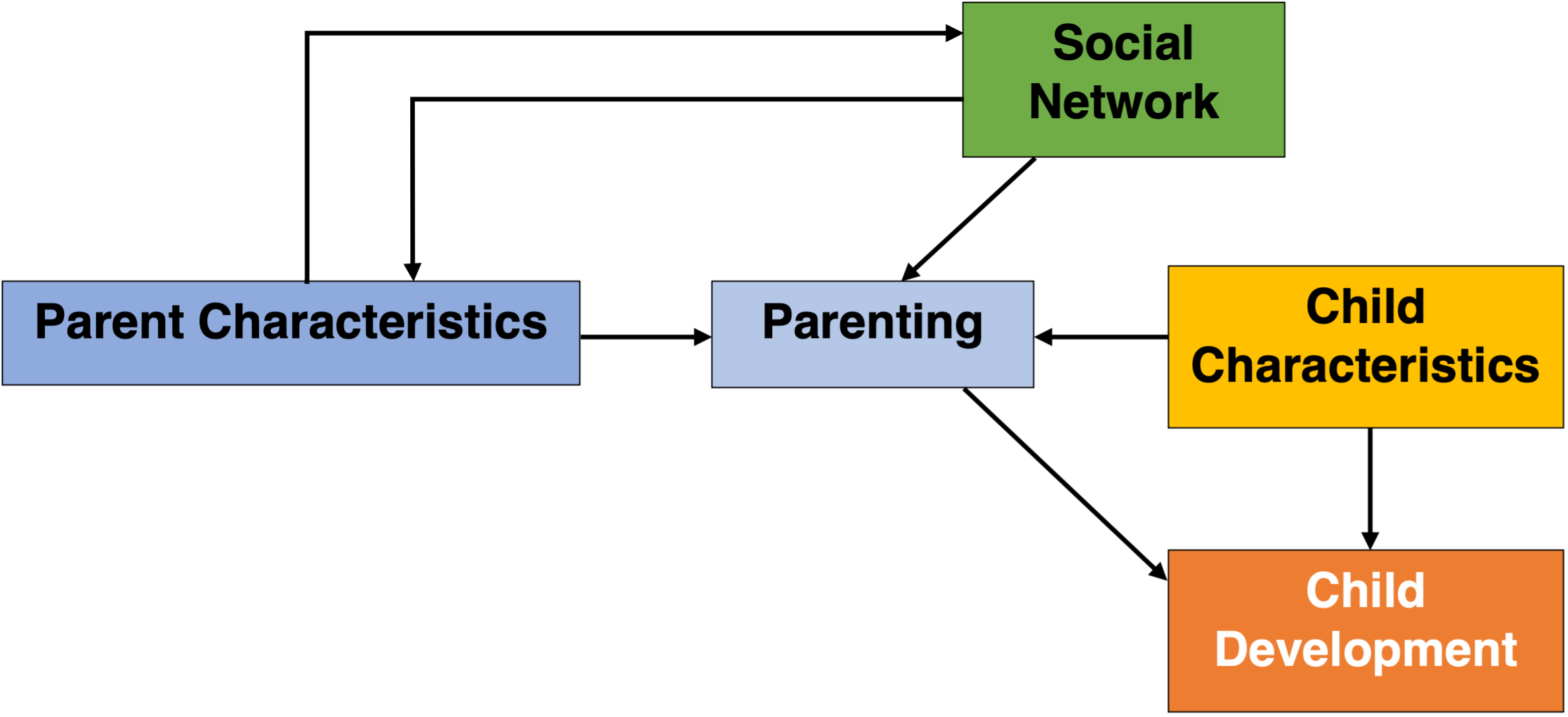

Belsky’s (1984) model articulates determinants of parenting as including three primary spheres: the individual parent, his or her social system, and the child. Parenting is influenced by individual characteristics of the parent, including developmental history (e.g., how s/he was parented) and personal traits (e.g., personality, mental health, maturational level of development). The child influences parenting and requires “fit” to the child’s needs through factors including developmental stage, health, temperament, and gender. Interaction with the social context provides the parent with information, influences, norms and expectations, resources, emotional, and practical supports that may shape, reinforce, and possibly thwart parenting. For example, social support in the form of practical assistance from family helps alleviate everyday stress, resulting in more positive maternal mental health.

Determinants work interactively to influence the practice, attitudes, and relational qualities of parenting, which have direct or indirect impacts on child outcomes. For example, a social cognitive perspective of parent development (Azar) holds that a parent’s understanding of the relational role evolves through the development of cognitive capacities that are shaped through interaction with the environment.

As parenting is, in part, a social construction, and the environment provides opportunities that scaffold learning and develop knowledge and identity (Marienau & Segal, 2006) to deeper, more complex levels. As the parent matures and grows in understanding of self relative to others (the needs of the child), and is surrounded and influenced by expectations of the social context, their perceptions and responses will change. The table below describes the “stages” of parenting that align with childrearing across a child’s development (Galinsky, 1987). These stages need more in-depth study to reflect other conditions of a parent’s life, such as having multiple children, gaining stepchildren, and child loss. They have also not been adequately applied across cultural frameworks. Nevertheless, they indicate change within the parent as an adult as related to child development.

| Age of Child | Main Tasks and Goals | |

| Stage 1: The Image-Making Stage | Planning for a child; pregnancy | Consider what it means to be a parent and plan for changes to accommodate a child. |

| Stage 2: The Nurturing Stage | Infancy | Develop an attachment relationship with child and adapt to the new baby. |

| Stage 3: The Authority Stage | Toddler and preschool | Create rules and figure out how to effectively guide children’s behavior. |

| Stage 4: The Interpretive Stage | Middle childhood | Help children interpret their experiences with the social world beyond the family. |

| Stage 5: The Interdependent Stage | Adolescence | Renegotiate relationships with adolescent children to allow for shared power in decision-making. |

| Stage 6: The Departure Stage | Early adulthood | Evaluate successes and failures as parents. |

The “stages”of parenting that align with childrearing across a child’s development, from https://nobaproject.com/modules/the-developing-parent referring to Galinsky, E. (1987). The six stages of parenthood. Perseus Books.

Belsky’s model also includes influences from the marital (partner/co-parent) or partner relationship and from work — both affecting the parents’ ability to parent and the parents’ own parenting behaviors. Chapter 9 will focus on work-family balance and technology and explore how the workplace can influence technological considerations in parenting.

A potential research question integrating these factors with relationship to technology might examine parents’ monitoring of a child’s use of social media. This parenting behavior might vary with parent age and understanding of technology (parent characteristics) and with the child’s age (child characteristics). We might then measure the time spent on schoolwork as an outcome, with our hypothesis being that parents who are comfortable with technology and children who are normatively developing may interact more constructively with technology for homework, leading to the child spending more time on school work. We might also incorporate social media, hypothesizing that parents’ discussion with friends about social media’s effects might influence a mother’s motivation to monitor her child’s time and exposure online while the child is using technology for homework.

A third model that respects individual variation is Super and Harkness’ developmental niche (1986), conceptualizing child-rearing practices as the outgrowth of caregiver beliefs intersecting with setting demands and cultural perspectives. With regard to their technology use with and for their children’s wellbeing, parenting practices are motivated by (or in response to) a specific setting for which parents are preparing their children to live. As parents acknowledge shifts in the world compared to their own childhoods, and the ways in which successfully operating in life is now dependent on comfort and skill with a multifaceted range of devices, applications, and settings that call for technology integration, their actions will reflect the worlds they know and the worlds they anticipate for their children.

Readers will note that these models offer perspectives on parents and parenting in a gender-neutral way. Certainly, there are models specific to “mothering” and “fathering” and to others who perform roles in less traditional, heterosexual, cis-gendered ways (e.g., non-biological parents, homosexual caregivers, grandparents conferring the role of primary caregiver). These models focus heavily on social and cultural constructions of the role, influences that reinforce or disrupt role expectations, unique elements of the role as played out by the individual, and shifts in perspectives about the role over time. Readers are encouraged to identify parenting models that speak to populations of interest as they interpret the ways in which technology is used and how the societal impact of technology defines and constricts the expression of the role.

Parenting as Represented through Information and Communications Technology Use

Technology use to fulfill parenting functions and aims

Parents use a variety of technologies and media to fulfill a range of parenting functions, from self-development, to knowing more about child development and parenting, to securing resources and social connections for the family. An important analysis done with my colleague Jessica Rudi in 2014 asked whether parents use ICT in ways that facilitate discrete and recognized domains of parenting (Walker & Rudi, 2014). If so, are there apparent trends in the types of ICT activities that align with those parenting goals? Our sample contained 1422 parents whose oldest child was 18. The mean age of the mothers was 37, with a range of 19–70, and the mean age of their children was 7, with a range from birth through 18. Like much of the early survey research on parents and technology, this sample unfortunately was predominantly white and well-educated, and therefore we cannot generalize the results to all parents. However, this was early work to indicate the range of ways in which parents use technology that fulfill all domains of the parenting role. Recent work by Livingstone et al. (2018) revealed similar data on the range of ways parents use technology for parenting.

Information and communication activities included the frequency of doing an activity for parenting. Respondents were asked to indicate whether the action and use of technology was done in general as an adult or whether it was done for parenting. For example, when they responded that email and texting were used for personal communication, they would be asked the degree to which this was done for parenting. Frequency of actions were measured as weekly or more often, so a certain level of activity was required for the action to count. The five domains of parenting were taken from the Parent Education Core Curriculum Framework (PECCFI) by the Minnesota Association of Family and Early Education (mnafee.org), which assists licensed parenting educators in Minnesota with the creation of curriculum for parents. The five domains are:

- Parent development: promote parent confidence, secure the parents’ philosophy of parenting, and explore perspectives related to parenting.

- Parent-child relationship: strengthen reciprocity, trust, and expressions of affection; ensure the child’s health and safety.

- Child development: understand children’s development and have reasonable expectations; promote all aspects of child development — physical, cognitive, social, and psychological.

- Family development: promote family time together, and manage family resources.

- Culture and community: build and maintain relationships with friends and professionals, seek support.

| Parent Development | Parent-Child Relationship | Child Development | Family Development | Culture & Community |

| Promote parent confidence, philosophy

Explore perspectives |

Strengthen reciprocity, trust, express affection

Monitor child’s safety, peers |

Understand development; have reasonable expectations.

Promote all aspects of child’s development. |

Promote family time together.

Manage family resources |

Build & maintain relationships with friends, professionals.

Seek support. |

| Discussion boards

Blogs, info sites Creative activities |

Comm. devices (text, cell phones, IM)

Connectivity (SNS) |

Information sources

Discussion boards |

Comm. devices

Entertainment, games, creativity Utilities |

Comm. devices

Connectivity (SNS) Discussion boards |

Parent use of ICT aligned with the five domains of parenting/parent education (PECCFI, MNAFEE.org). Adapted from Walker & Rudi, 2015.

Parenting functions as listed on the survey were coded to align with one of the five domains in the parent education framework. We then observed, by type of technology, how parents used technology to fulfill that particular function. With regard to parent development, approximately 40–55% of the parents identified using technology to resolve conflicting information, explore perspectives, confirm their beliefs, express themselves, and provide advice to others. Smaller portions indicated that they use technology to communicate with the child or to keep up with the child’s friends (note: the average age of children in the sample was 6). The highest numbers, at more than 50%, were indicated for fulfilling child development through seeking information, identifying problems, and normalizing parents’ observation of children’s behavior. Percentages were high as well for the family development and the culture and community domains. In family development, 92% of parents reported using technology for communication with non-residential family members. Technology was also used by more than half to review products and to have fun with the family. With regard to culture and community, more than half reported using technology to communicate with friends, make professional connections, and receive support.

The types of technologies used to fulfill each of these parenting actions varied. For parent development, discussion boards, blogs, and creative activities were most frequently mentioned. Discussion boards and information sources were also identified when seeking information about child’s development. For the parent-child relationship, communication devices were obviously used (e.g., texting, calling, instant messaging). For family development, communication devices were used for connecting with non-residential family members, and for shared entertainment and games. Utility functions such as navigation tools or websites were used for purchasing goods for the family. And finally, communication devices, discussion boards, and social media were mentioned for building community and maintaining a family culture.

Through this simple research, we can see that the same technology that promotes the parents’ own development can be used to strengthen knowledge about child development, while also building a stronger social network of support. No one device or application fulfills all functions, yet a single function (like learning more about child development or building parent confidence) can be facilitated by a variety of tech. These applications reflect technology popular a decade ago; a more contemporary investigation would likely address specific types of social media, videoconferencing, and use of smart devices like Alexa.

Individualized use

Research indicates that parent technology use varies, a finding that validates our understanding of individual differences. Use is complementary to that of available resources, devices, or applications; it also supplements what is not available elsewhere. Parents seek information online to complement to other information sources. While they may read blogs, Google, and read websites, they also are talking to pediatricians and to friends and family members, and may be reading books or parenting magazines (Duggan et al., 2015). Parents also draw on personal experience. And parents use communication tools as a complement to face-to-face connections with family friends and others. While parents will text, FaceTime, Zoom, and send private messages to their children and others in their lives, for many these are a complement to face-to-face interactions.

Virtual contacts complement or enhance what is available socially offline, providing, for example, additional ways to connect with families and expanding the size of social networks. A parent may have networks of friends at work and in the neighborhood to whom she turns to for advice and information on parenting. A Facebook group for parents of young children can exist for her as a complementary source of information and support to her offline resources.

Finally, parents’ use of technology can supplement what is missing in offline lives. Early research on parents’ internet use identified that parents most likely to use discussion forums were those whose children had special needs (e.g., Scharer, 2005). Parents went online to find a community and information not available to them in their face-to-face world. They found great relief communicating and connecting with others who had experience raising a child who had the same condition or diagnosis, a community in which they felt no judgment and could share their own experiences.

Steinmetz’s Time article (2015), “Help, my parents are millennials,” describes variations in attitudes, opinions, and behaviors between those who are Millennials (born between 1981 and 1996), Gen Xers (born between 1965 and 1980), and Baby Boomers (born between 1945 and 1965). Millennials, for example, are more likely to purchase gender-neutral toys for their children and to report feeling judged by other parents. Consider how these attitudes might play out differently in ICT interactive behavior. Now that young adults represent a new generation (Gen Z, born after 1996) what attitudinal or perspective shifts might be revealed in their parenting, and how might their parenting interests be reflected differently in their technology use?

Regardless of demographic differences, parents are humans and will vary in their interests.

Interesting research has identified typologies of parents in terms of the time they spend online. Some parents are information seekers, using technology primarily to read information about child development and children’s health and well-being. Some love using a variety of social media discussion groups, Facebook pages, Tik-Tok channels and more to interact with other parents and extend their time offline in social ways. Some parents are content creators, writing blogs and curating product information on products to encourage dialogue and often to seek emotional support and validation for their parenting.

These relationships between parent technology use and their parenting and interactions with children are not always clean, nor directional. As demonstrated by McDaniel and Radesky (2018), a bidirectional relationship can occur between parent and child and technology. Their study revealed that child behavior can relate to stress in the parent, who turns to technology for distraction, in turn exacerbating the children’s behavior that is causing the stress.

In summary, as with other technology users, parents use a range of devices and applications to fulfill a range of functions. As with others, they vary in their use, attitudes towards use, and comfort with use. With regard to the parenting role, parents interact with their children with technology, using technology to parent. Parents also parent about technology.

The next chapter is on parent-child relationships and technology. Technology plays a role in influencing parents’ knowledge, attitudes, skills, and beliefs. Parents gather and exchange information, and seek out support from others. Technology and the internet can complement or supplement what is available or missing from parents’ offline lives. Regarding parent learning and social support, technology and virtual environments can play particularly meaningful roles in mobilizing the social resources that aid in parent learning, behavior, interactions with their children, and child outcomes.

Parent Technology Use as Direct and Indirect Influence on the Child

Given the actions of parenting as revealed through behaviors, attitudes, skills, and knowledge directly with or on behalf of their children, and the internal, historical, social and environmental influences on parenting, there are three dimensions of technology use by parents:

- Parenting ABOUT technology

- Parenting WITH technology

- Technology use AIDING the parent and parenting

After a brief introduction here, the first two actions will discussed in more depth in Chapter 7. More attention in this chapter will be paid to the third way that parents use technology: on behalf of themselves as parents.

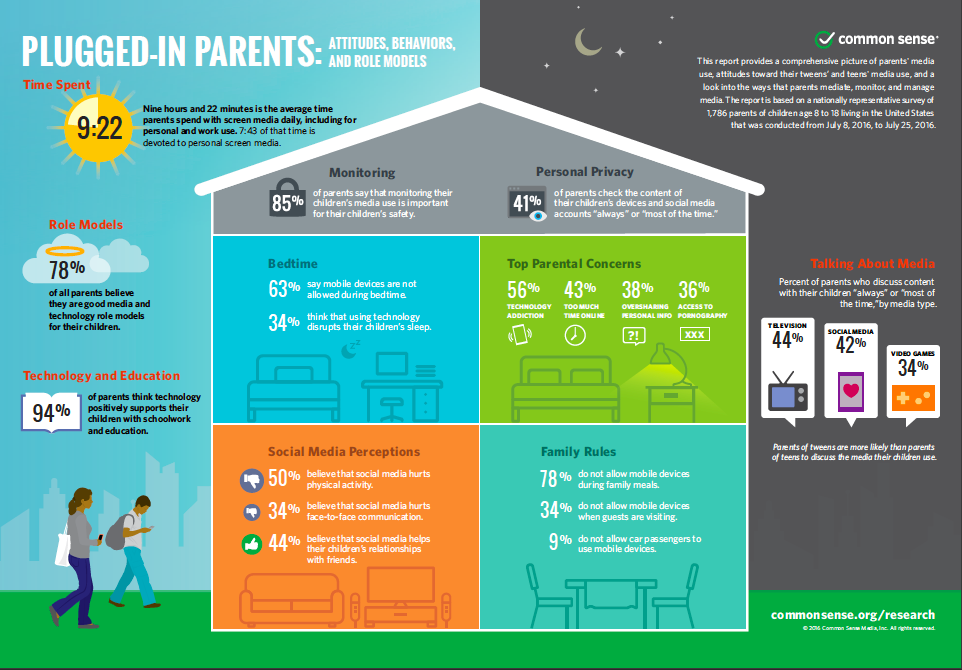

Parenting about (the child’s use of) technology and parenting the child with technology

Adding to parents’ scope of practice is their child’s well-being in the use of information and communications technology. Therefore, among many other topics, parents parent about the content topic of children’s technology. Parental monitoring, asserting controls, and mediating screen time have been the centerpiece of research and action for childrearing support for at least the last decade (Auxier et al., 2020; Blum-Ross et al., 2018; Coyne et al., 2017; Livingstone & Blum-Ross, 2020; Livingstone et al., 2018; Nathanson, 2018; Wartella et al., 2013). On this, parents vary widely, influenced by their perspectives and understanding of technology’s effects. For example, parents’ attitudes along with their own media use influence young children’s use of technology in general, and specifically related to math and science. Parenting confidence and parent media patterns also influence their actions towards children’s media use. Parents with greater confidence around technology are more likely to monitor and interact with children around media use (Commonsense Media, 2016). And parents vary in terms of their own behavior around media consumption. Households that are more media-centric have more screens that are on for more hours of the day, and attitudes toward children’s technology ownership and use are more lax, compared with those of parents who are more media-moderate or media-light (Wartella et al., 2013).

These influences aren’t reserved for families of younger children and teens. During the pandemic, parents’ attitudes toward using technology for distance learning in universities showed variation. Those less concerned about financial impacts, and who saw benefits held more favorable views of distance learning technology (Mahasneh et al., 2021), which factored into their encouragement of their children. Chapter 7 explores this topic in more depth.

As illustrated by this graphic of parents’ technology use relative to that of teens, parental monitoring and talking about media with children is balanced with their own sizeable consumption of screen time and with modeling media behavior to children (Lauricella et al., 2016).

Technology is also a vehicle through which parents’ parent. They communicate, support, nurture, and guide their children through texting, video, and voice communication (Dworkin et al., 2019). Time interacting together with technology, such as through gaming, co-viewing movies, or engaging in a “maker space” (a facility for creating with materials and developing critical thinking skills; see www.makerspaces.com), can strengthen parent-child cohesion (Coyne et al., 2017; Commonsense Media, 2016; Ito et al., 2020). Yet parents using technology to parent can produce conflict in the parent-child relationship as children feel their agency threatened through un-agreed upon monitoring (Blackwell et al., 2016; Coyne et al., 2017; Commonsense Media, 2016; Livingstone et al., 2018). Personal use can also create a distraction and diminish attention to caregiving, which affects the quality of the relationship (Beamish et al., 2019).

Technology use AIDING the parent and parenting

A third way in which parents use technology is as support for their parenting. In this way, technology plays a more indirect role, connecting parents to information, social and emotional support, validation, and skills development. Reading helpful tips on infant sleep on a parenting blog, for example, may boost confidence in ways that show in childrearing. There is, of course, also the possibility of negative influences on the parent, perhaps through negative messages or challenges to their perspectives and identity. As an example, parent confidence may be affected when other parents post about their “perfect” children on Facebook. To examine parents’ use of technology to support themselves in the role is to see the parent as a developing adult, and the use of technology as fulfilling personal and adult roles as well as parent roles.

Gathering information

Gathering information about child development and health is a major way that parents use technology to support their parenting competence and comfort (Baker et al., 2017; Livingstone et al., 2018; Myers-Walls & Dworkin, 2015; Zero to Three, 2016). Recent data suggests that 40% of U.S. parents with children up to age 17, and 65% of Australian parents of children ages 2–12, get information from the web (Auxier et al., 2020; Baker et al., 2017). Parents who are of higher socioeconomic status and those with children with special needs are more likely to use online help (Zhang & Livingstone, 2019). Online sources are used to complement parents’ other, more personal, and proximal sources, including friends and family, teachers, pediatricians, and other professionals (Myers-Walls & Dworkin, 2015; Zero to Three, 2016).

While this can be useful for problem-solving and resolving parents’ answers about childrearing and child development, there is the potential for misinformation. In a Wired magazine article in early 2022 (Jankowicz), the author examined pregnancy-related apps for new mothers. She notes that the majority of apps are run by “lifestyle” companies powered by advertising revenue. The aim is less about supplying accurate information about the stages of pregnancy and transition to parenthood, and more about connecting the user to other platforms and using user data. Worse, the sites can promote potentially harmful misinformation about pregnancy and childbirth.

And while research suggests that a minority of parents participate in parenting education online (at least, pre-COVID; Walker & Rudi, 2014; Zero to Three, 2016), delivery of parenting education programs wholesale or as a complement to face-to-face efforts is increasingly available (McLean et al., 2017; Walker, 2020). Demographic variation reveals that parents in lower socioeconomic groups, particularly those with less formal education and who live in higher-stress environments, are more open to getting information from websites than to participating in seminars or individually tailored programs (e.g., evidence-based programs adapted for online delivery). This suggests that outreach methods need to appeal to a wide range of parents to reduce equity gaps in participation. Given the conversion to online-only parenting education programming during COVID-19, it will be interesting to see if attitudes change with a return to face-to-face opportunities. Chapter 11 will explore technology applications in the delivery of parenting education.

Exchanging social support

Informal exchanges with peers through social media, seeking out information on childrearing on a website, pursuing creative ways to express oneself by blogging or interest board (e.g., Pinterest) and videoconferencing with other parents all contribute to parents’ mental health, sense of identity, and feelings of connectedness (Walker & Rudi, 2014). Meaningful support for the parenting role comes through parents’ use of social media and other social technologies to interact with other parents, family, and friends. In the U.S., 29% of parents report getting information from social media, and 19% from message boards. Participation in discussion forums and social media offers parents emotional validation, normalization of concerns, and tailored information for problem-solving and decision-making (Drentea & Moren-Cross, 2005; Walker & Rudi, 2014). Indeed, some of the earliest research on parents’ technology use was in the health care community, as nurses observed parents with special needs children using discussion forums to exchange information and ideas (Scharer, 2005). More recent research has identified social media and blogging as a form of expression and support that is valuable for parents of children with special needs/health challenges (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017; Nagelhout et al., 2018) and for other marginalized groups of parents, including LGBTQ (Blackwell et al., 2016). And using social media during transition points in parenting can be validating and bridge identity shifts to new roles (Bartholomew et al., 2012). Younger parents and mothers are especially likely to use social media to share information about their children, compared with fathers and older parents (Auxier et al., 2020; Steinmetz, 2015). Blum-Ross and Livingstone (2017) write that “sharenting” helps manage the juggling of identities as parent, problem solver, and information seeker. Still, fathers and grandparents, foster parents and other caregivers are a significant presence among bloggers. Blogging, and interacting on social media, enables parents and caregivers to transmit images and pictures of the parent’s child and of themselves in ways that deepen the sense of themselves as caregivers and perhaps anticipate themselves into the future.

For some parents, however sharing their parenting experiences and children’s lives online brings up feelings of guilt and ethical dilemmas. And as noted, such use can also override children’s privacy and opinions on the use of their personal information. In preparation for a radio discussion on children’s privacy online, the author ran across a Buzzfeed news item on “pumpkin butt.” Parents submitted pictures of their baby’s bottom painted with a pumpkin for a voter competition. While to many this may be cute, and it may provide some parents a sense of connection and even pride if their baby is voted for, it can also be seen as an invasion of the child’s privacy and contributing to the commodification of children’s bodies.

“Sharenting” online can offer parents ways to express themselves in the caregiving identity, yet some do so with a sense of guilt knowing the ethical dilemma of invading their child’s privacy.There is particular value in virtual exchanges that strengthen parents’ social capital and its personal and parenting benefits (McLean et al., 2017). Definitions of social capital vary by structural (e.g., network ties that forge and define relationships) or content impacts (e.g., quality of interaction and exchanges across ties that maintain a sense of cohesion). Person-to-person repeated exchange within groups can produce familiarity and feelings of trust, strengthening bonding social capital. Parents’ interactions through social networking can also form bridging social capital, or connections to new networks which offer new, more novel connections, and the opportunity to learn new information about parenting. Cochran’s perspective on parents’ personal social networks (Cochran & Walker, 2005), supported by research and later applied to parents’ use of the internet (Walker & Greenhow, 2010), indicates that heterogeneous connections are positive for parents through the diversity of perspectives and acquisition of novel information.

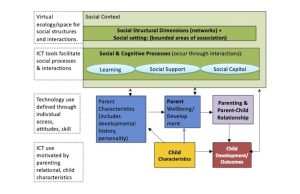

There is evidence of the valuable impact of social network membership and processes for parents’ actions and attitudes in parenting and, as a result, positive albeit indirect impacts on child outcomes. Given what we know about relational processes that promote learning by adults (e.g., McShane et al., 2014; Brookfield, 2020), the author has asserted the value of these online social connections as providing social learning outcomes in complement with social support and social capital (Walker, 2015). Jointly, these social products inform and support the parent’s assets brought to parenting. The figure below demonstrates the complexity of factors involved in parent technology use intersecting with social network membership, engagement, and eventual outcomes. It demonstrates on the right, the social structures and processes that provide resources to parents, which contribute to the parent’s well-being, the relationship with the child, and potential outcomes. These social elements also take place in virtual worlds and through the use of digital media (left). Access to the internet and digital media, and skills and comfort in using them, further vary parents’ access to and use of their social supports as assets in their parenting.

When interacting online, particularly using social media, some parents proceed with caution. Online interactions for parents can be challenging for some. Fear of judgment, self-comparison, and diminished confidence in childrearing can result (Steinmetz, 2015). Additional researchers have shown that discussions can also promote particular perspectives. For example, Madge and O’Connor (2006) note that while mothers’ exchanges on parenting through discussion forums were viewed as helpful at the time, those taking to the internet reinforced a more traditional stereotype of mothering. In the search for validation and content — an issue that affects all parents (Cavalcante, 2015; Fraser & Llewellen, 2015) — individuals in caregiving roles may need to find the best “fit” between content and their values for the experience to be most meaningful.

With this background on parenting revealing intentions and goals of those who hold this role in families, we begin to see the ways that ICT can help to fulfill those goals and how differences in access, comfort, skill using technology, and parent profiles reveal variation in this population. In this chapter we offer an essential though often under-discussed dimension of parenting: parent self-development and self-care. Indeed, social media, applications, internet searches, and exchanges of information present an array of opportunities for parents to find support for the parenting role.

- This is just one of several parenting pyramids characterizing parenting roles and processes. See, for example, the Parenting Pyramid from the Arbinger Institute, which embeds guidance within the relationship: https://content.byui.edu/file/91e7c911-20c5-4b9f-b8fc-9e4b1b37b6fc/1/Parenting_Pyramid_article.pdf ↵

- How ironic then that it wasn't too long ago (1998) that a book in the popular press by an independent researcher stirred up conversation whether parents even mattered. ↵

- A word on the word “competency:” it refers here to the skills applied to caregiving, rather than a qualitative assessment. There are volumes of research on this concept, and readers are encouraged to see how scholarship defines and measures “competent” parenting. ↵