Chapter 8: Technology Use for Family Communication and Connectivity

I know it is wet and the sun is not sunny, but we can have lots of good fun that is funny.

― Dr. Seuss

Chapter Insights

- Many ICTs (applications such as WhatsApp, FaceTime, Zoom, Email, texting, messaging, and Instagram) play a role in family communication and feelings of connectedness. Yet there may be challenges these applications introduce to effective family communication.

- Early research on family communication and technology revealed the value of interactive technologies and feelings of connectedness. Still there are differences in effectiveness depending on family membership.

- Videogames offer a number of benefits and challenge to family connectedness.

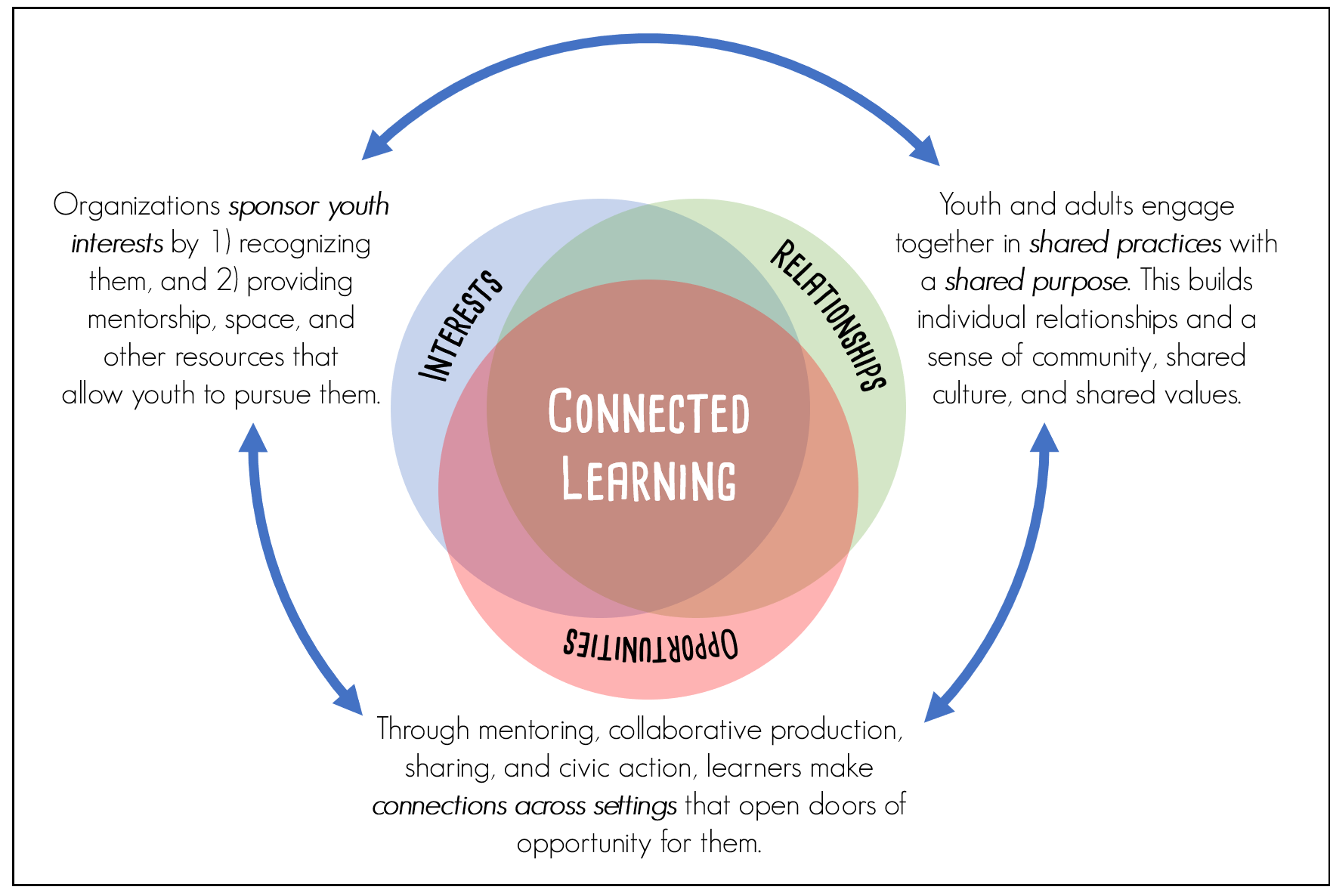

- The concept of connected learning values relationships when the individual explores interests using technology. Parents can function as “learning hero” and facilitate children’s learning beyond the classroom.

- Families can create technology together. An example offered in the chapter is that of a father and his two children who do an almost-weekly podcast. Consider ways that engaging with children around technology creation can strengthen family closeness/cohesion and demonstrate flexibility. Such an activity can also contribute to individual family members’ development.

- Key to family joint technology use is the set of rules families establish together about when and how technology is used. These rules include when family members are together, in the household. Consider the values and norms that families create for day-to-day functioning and the well-being of their members. ICT use is an extension of those values. Members’ use can also be a disruption of those values in ways that call for conflict resolution.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

Introduction

We’ve previously discussed technology use within the family and across families. In this chapter, we examine more specific ways in which families use technology as families. We’ll look, for example, at the role that technologies like FaceTime and Zoom play in family communication and feelings of cohesiveness, for example, and at how specific technologies like videogames and streaming media content are used for joint entertainment through co-viewing and interactive participation, contributing to feelings of cohesiveness and familiarity, and encouraging shared interests. Participation with children in these activities offers numerous benefits for parenting as well, and impacts children’s development. And during COVID, communication, interactive, and creative technologies meant ways for families to stay together, play together, cope with the strain of isolation, and find deeper means for satisfaction.

As a quick review, we looked at the family as a system open to external and internal forces. As the whole of the system is dependent on the interactivity and full functioning of all family members, technology was viewed as an influence external to the family, on individuals and subsystems in the family (e.g., a parent and child), and on all family members jointly. The family structure includes an understanding of the roles played by individuals within it.

We also examined how differences in technology use within the family illustrate the flexibility needed to embrace members’ own preferences and needs. Whole family differences helped convey how family units are subject to wider ecological system resource availability and constraints that can affect technology and internet access, values for use, norms and behaviors, and achievements. Limited access can also affect the voice and presence families have in social and political discourse.

Technology use by families and family members is measured by practical indicators, including:

- Device ownership (which, how many, which model, how many different).

- How devices are used and for what purposes.

- Device or application frequency (e.g., minutes per day, hours per day, days, interaction events).

- Whether device use is individual or shared.

- Whether device or application behavior is problematic — e.g., addiction, being a tech luddite.

- How members use tech by device, application, function, and their attitudes and skill differences. Variations by member use; factors such as age, employment, and attitudes that influence these variations.

These dimensions are important to keep in mind as we explore use by families as a whole, or by subsystems within the immediate and extended family, along with family-level outcomes.

Research on Family Technology Use, Communication, and Connectedness.

Researchers of family dynamics and communications technology/media hold that the use of devices and particular means and applications impacts the meaning that family members give to their interactions, and creates shared realities. In turn, these shared realities deepen the sense of family norms, values, and feelings of connectedness. When used constructively — and with an awareness of potential conflict that can arise between family members due to differences in comfort, skill, and perception of technology — media can thus be beneficial in strengthening the bonds that create the sense of family.

Early research by Padilla-Walker et al. (2012) examined types of technologies used by families (specifically parents and their adolescent children) and those more strongly related to families’ feelings of connectedness. As previously discussed, connectedness is a warm, loving, positive relationship between parents and child/family members. Connectedness was measured using the five items of the warmth/support subscale of the Parenting Styles and Dimensions Questionnaire-Short Version (PSDQ; Robinson et al., 2001; e.g., ‘‘I have warm and loving times together with my child/my parent.’’ Each item was measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Cell phones, videogames, and co-viewing media showed the most significant and positive relationship to family connectedness. Email and social networking did not indicate strength related to the outcome variable. The authors determined differences by family characteristics: parents with a higher level of education reported more connectedness related to technology use.

The authors posited that co-viewing of media indicated shared interests and fostered shared communication, and that if children and parents interacting together with media, and children teaching parents how to use various media and technology, bring the potential to both reduce the digital divide and increase a sense of family connectedness parents and children agree on media viewed together, each may have a better understanding of the other, which can facilitate shared discussion during or after the program. These findings relate to those of Nathanson (2002), who earlier identified the role that co-viewing media had on parents’ ability to mediate content and children’s exposure. While a smaller portion of teens reported playing videogames with their parents, co-playing was related to the level of family connection. And as mentioned in the previous chapter, children and parents interacting together with media, and children teaching parents how to use various media and technology, bring the potential to both reduce the digital divide and increase a sense of family connectedness.

Email and social media. In the Padilla-Walker et al. study (2012), email and social networking were not related to connectedness. Email offers asynchronous communication, which may seem less personal, and more like communication that just carries news and information, particularly as more immediate methods of texting and private messaging are available. In the author’s own collaborative research with over 1,500 families around the same time (2011), we determined that type of technology varied by family member. Email and social networking are particularly popular with extended family, while texting — a more intimate form of communication — was more likely to be used with one’s children and the other parent (Rudi et al., 2014). Since the time the study was conducted, there has been little substantive change in how email is used or perceived among family members.

Social media, in contrast, has greatly expanded in terms of perception, use, and variety of applications. The 2012 research by Padilla-Walker et al. reported minimal interaction between parents and teens on social media, citing limitations in personal expression (e.g., Twitter’s 140 character limit) and the perception that using social media was only between friends. More recent research, however, indicates that aspects of social media can strengthen family connectedness. A 2022 review of the literature by Tariq et al. identified 14 articles on social media use and family relationships/family connectedness. As with the Padilla-Walker et al. (2012) study, the majority of articles focus on parents and adolescent use. Connectedness is related in part to the dynamics of the parent-child relationship; adolescents or young adults, for example, may feel their privacy is at stake when parents “friend” them on social media. Stronger outcomes related to connectedness were determined in studies that focused beyond parents, and on integrated connections with siblings and extended family (e.g., feeling closer by having another outlet for sharing information). Yet the authors note that the literature is sorely limited, with the majority of focus on teenagers and young adults rather than whole families, and observe that questions rarely address the motivations for family members’ joining social media or how social media use relates to connectedness.

Also limited in the research is the range of types of social media applications, with a strong preference given for Facebook. Tariq et al. (2012) observe a study (Nouwens et al., 2017) that highlights adults’ variation of application use depending on the contacts and users in that application. In other words, parents use of a platform like Instagram or TikTok would depend on whether their child uses it, or they know other people on it.

Even earlier research by Stern and Messer (2009) looked at means for connection with relatives: email and cellphones were used to communicate with more distant relatives; face-to-face visits were used more locally. When considering measures of closeness, the authors concluded that frequency of contact may not be the best indicator of closeness. Rather, people select the method and behavior for staying in touch with others that relate to the level of closeness desired. In other words, “people use the technologies available to them to fill the niches in which they believe they are most useful.” (p. 671). As we’ve come to understand the capacities of technologies and differences in individual comfort, skill, and access, we see that technology used for communication in families can be based on factors that complement emotional closeness and proximity.

Since 2012, and especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, new technology has evolved for family communication: videoconferencing. Through applications like FaceTime, Skype, and Zoom, videoconferencing enables real-time communication that is more complete (or “media rich”) than voice- or text-only communication. As Lebow (2020) observes, social science research will, over time, unveil the values and costs of depending on videoconferencing for family communication during COVID, as families experienced significant loss, strain, and attempts to maintain family rituals and celebrations. Other variables on family functioning during COVID related to reliance on virtual technologies for communication, include accommodating disparities in technology access and skill, and the systemic impacts of supporting family members who face the additional strain of factors related to mental or behavioral health (e.g., access to AA meetings).

Family Variation in Communication and Connectedness via Technology

Karraker (2015) identifies how the use of technology for communication can help families “transcend spatial limitations and provide for identity and cultural renewal” (p. 60). Families who may depend on technology to maintain relational communication and the flow of information include transnational families, divorced/noncustodial families seeking connection and coordination, military families during deployment, and commuter parents. Forging social connectedness in new locations can be a critical lifeline for migrating families (Farbenblum, et al, 2018; McAuliffe, 2021).

This video depicts a military family whose members rely on videoconferencing technology to stay in touch. The father is deployed, and his wife and school-age children connect to share each other’s days. The clip promotes a positive association with the family staying in touch during deployment. Similarly, we can consider connections with extended family — particularly grandparents — through videoconferencing and other communication forms such as email, social media, and collaborative tools. During COVID-19, especially, families relied on virtual visits when members couldn’t travel and/or were in quarantine (Rose et al., 2021). Some families found improved communication and connectivity with young adults; others held nightly family dinner times virtually so all family members could stay connected (Joyce & McCarthy, 2021). Voida and Greenberg (2012) suggest that playing videogames across generations improves the opportunities for the sharing of activities and experiences, thus improving family relationships.

Yet consider some of the possible consequences or downsides of relying on technology for continued communication. When we experience the lack of physical touch, smell, and sound, Karraker (2015) asks, how much is it really like being there? Over time, does it become easier to meet virtually, eventually bringing about disruption? She notes, “While technology can enable families to reduce the strain spatial distance places on intimacy, technology may also be the ‘antithesis of intimacy’ (Parrenas & Boris, 2010, p. 13). Most likely, as with every social change confronted by the family, technology will sometimes enhance long-distance intimacy for global families and will sometimes diminish it, while certainly changing the dynamics of global families in a digital age.” (Karraker, 2015, p. 69).

Videogames and Co-viewing Media

Playing videogames as a family or a family subset, such as a parent and a child, can be a marvelous way for technology to build closeness and cohesion. While research supports the benefits for children’s physical development (through using handheld devices or activities with Wii ), learning, and social and psychological well-being, and has identified possible challenges through contributions to anti-social and aggressive behavior, research has also explored the impact on family time together, satisfaction and coping. Engaged Family Gaming is a site promoting the benefits of gaming together and providing resources for parents.

An annual report by the Entertainment Software Association (ESA, 2022) provides statistics on who games and on the benefits of gaming. It indicates that 66% of Americans play videogames, including ¾ of those over the age of 18, and with numbers fairly evenly divide between males (52%) and females. The majority (69%) of families in the U.S. have at least one member who plays videogames.

In Chapter 6, we discussed the roles and functions that parents have in parenting; in Chapter 7 we looked further into parents’ roles in mediating and moderating their children’s technology safety and use. Here we focus on joint consideration when family members interact with one another when playing videogames or co-viewing media. When her daughter was about 8, the author played Nancy Drew Mystery games alongside her. The games were sold on DVDs at the time (downloads came later), and formatted for a PC. The games were challenging and filled with depth of information on specific content, as each game had a theme (e.g., history museum, aquarium, Egypt exhibit). To solve the mystery meant solving any variety of puzzles, using keen eye-hand coordination, and employing memory of clues. They could take days to solve. Consider all the ways in which playing Nancy Drew with her 8-year-old enabled the author to fulfill her role as a parent[1].

In their 2022 report on videogames, the ESA observes reasons why parents play videogames with their children.

- It’s fun for all of us.

- It’s a good opportunity to socialize with my child.

- My child asks me to.

- I enjoy playing videogames as much as my child.

For example, 90% of parents are present when their child acquires a videogame. And 9 out of 10 require their children to ask permission before purchasing a game. Nearly all (94%) parents pay attention to the videogame played by their children. Three-quarters (77%) report playing videogames with their child at least once a week — up from 55% in 2020.

Over two-thirds (71%) note that playing videogames has a positive impact on their child. And even more (88–91%) agree that they help children learn collaboration and problem-solving skills. With regard to connectivity, most people (83%) play with others ,with 56% playing with friends, 35% with a partner or spouse, and 32% with other family members.

Research into family videogame playing validates its value to family communication, family closeness, and family satisfaction. Wang et al. (2018) surveyed 361 adults with children in middle childhood through adolescence about their game playing and family well-being variables. Their quantitative analysis revealed direct effects for both frequency in game-playing and family closeness and satisfaction, even after controlling for age, gender, and education level. They also determined that family communication moderated (had an influence on) the effect of playing and family closeness, but only for those families with lower levels of family communication. Families reported finding fun, spending time together, and feeling closer when they played videogames, presenting a positive picture of the activity.

Pearce and colleagues (2021) examined the use of the videogame Animal Crossing with the idea of using entertainment as a way to cope during the COVID-19 pandemic. From interviews with parents and their children (in some households, both parents or all children were not interviewed; children ranged from 5–15 years), the authors found that playing the game contributed both to emotion-focused coping and problem-focused coping. Emotional-focused coping includes escapist/avoidant, distraction, mood management, emotional expression, and spending time together. Problem-focused coping included being occupied and passing the time, which offered parents a way to protectively buffer stress. Playing the game lent to being part of a routine, which related to resilience by individuals and the whole family. Finally, playing offered a way to socially interact, something which, during the pandemic, was very limited. Children expressed that when they played the game with others there were “kind of hanging out with people” (p. 12).

Connected Learning

In Chapter 5 we considered the role of technology in children’s learning. Traditionally, we think of “educational technology” as that used by teachers and schools in schools and to assist children with homework. But the connected learning paradigm unbound learning from a place or space to follow the individual’s pursuit across what Barron (2006) refers to as a “learning ecology.” As an example, a child interested in dinosaurs may talk about them in class as part of a science curriculum. She may learn about different dinosaurs, their names, their anatomies, and whether they were predators or prey. Beyond the classroom, however, she may further explore dinosaurs online, in applications and games, in ways that sharpen her knowledge and ability to differentiate. Her parent may plan the family vacation around a special exhibit at a museum in a large city. An adventure to the seashore with her 4H club enables her to look for fossils, which she then takes back home and, with the help of her parent and the internet, identifies as part of the Paleolithic age.

Connected learning uses technology, space, time, and especially the interest of other people to build engagement in learning. Those who assist the child in this engagement are called “learning heroes.” Parents’ funds of knowledge can flow into family activities (Rogoff, 2003) to connect children to history, culture, and experience, further tying together family members’ understanding and interests. Beyond family-specific opportunities for connected learning, the concept, when applied to minority youth and their exploration of new media and technology for learning, creativity, and personal identity, finds real promise (Watkins et al., 2018). The Digital Edge provides results from a year-long ethnographic study of adolescents at an urban high school, incorporating interviews with teens, parents, and teachers, and observations of the technology-enhanced settings in school and especially out. Results suggests that teens’ “eager adoption of different technologies forges new possibilities for learning and creating that recognize the collective power of youth: peer networks, inventive uses of technology, and impassioned interests that are remaking the digital world.”

The figure above is taken from research by Barron et al. on family involvement in children’s digital learning (2009). The table below lists the fluency-building items for which children indicated frequency in creating with the aid of their parents. The research identified both the learning ecology supporting children’s technological fluency, and the role that parents play in facilitating that learning. Readers are encouraged to visit or subscribe to the Connected Learning Alliance (https://clalliance.org/about-connected-learning/) to explore an array of publications and projects that indicate the intersecting role of interests, relationships, and opportunities, many of which involving families, as mechanisms for fostering positive youth development and family life.

| Appendix A: Fluency-Building Items from Interest, Access, and Experience Survey

|

||||

| How often have you done the following computer-related activities?

|

||||

| (please mark only one box per item) | Never | Once or twice | 3 to 6 times | More than 6 times |

| Created multimedia presentations that included pictures or movies or sounds using PowerPoint or another application | ||||

| Written code using a programming language like C, Java, Logo, Perl | ||||

| Made a publication such as a brochure or newspaper using a desktop publishing program like PageMaker or Word | ||||

| Started your own newsgroup or discussion group on the Internet | ||||

| Created a website using an application like Dreamweaver or FrontPage | ||||

| Hand-coded a webpage using HTML | ||||

| Published a site on the Web so that other people could see it | ||||

| Created a piece of art using an authoring tool like Photoshop or Paint Shop | ||||

| Designed a 2D or 3D model or drawing using a tool like CAD or ModelShop | ||||

| Built a robot or created an invention of any kind using technology | ||||

| Used a simulation to model a real life situation or set of data (e.g., population over time, the spread of disease, or speeds with varying resistance) | ||||

| Made a database | ||||

| Created a digital movie | ||||

| Created an animation or cartoon | ||||

| Created a computer game using software like Game Maker or through a programming language | ||||

| Created a piece of music | ||||

Adapted from Barron, et al (2009). Parents as learning partners in the development of technological fluency. International Journal of Learning and Media, 1(2), 55-77.

Joint Exploration of Media and Technology

Family podcasting

An even more tangible way that families can be involved in cohesive ways with technology is to co-create technology together. This may include building a website or maintaining a social media page, podcast, or a YouTube channel. A good example of this is the Nowatski family. Beginning in 2015, Al (the father) and his two children, Liam and Anna, created the Children of the Force podcast. At the time, the children were 6 and 8, respectively. They started the podcast because the family often talked about Star Wars. Weekly, they talk about all things Star Wars — digging into the lore, current films and TV shows, conventions, and news. The conversation moves to current events and the kids’ opinions on a wide variety of topics. The podcast lasts about an hour, and as the children have gotten older and more involved in school, friends, and activities, they sometimes skip a week. Readers are encouraged to check out the Learning Activity that centers on this podcast. If watch the author’s interview with the family (Liam and Anna are now in their teens), you can consider the ways in which doing the podcast as a family contributes to the family’s cohesion, communication, and demonstration of flexibility.

Maker spaces

Ito et al.’s 2020 report on Connected Learning addresses how co-creation can be beneficial to children and the family. Co-creation can occur, for instance, in libraries that offer “maker spaces.”

Intergenerational learning environments can offer non-traditional configurations of learners using technology together to create opportunities and reimagine relationships to technology and the natural world. Projects that have been studied include technologies with indigenous families, constructing identities through making projects, parents collaborating with children to learn, and eliciting family sense-making with language and culture in digital projects.

Learning through and about technology together

Tech Tales is a series of workshops that center on indigenous knowledge systems through storytelling, family culture, family values, intergenerational sharing, and robotics. Through comparative case study research, the scholars explored processes used by families in creating their stories. An example of this project, with a focus on family engineering, is discussed and shown here. As the description of Robotics and e-textiles backpacks for family learning says:

In this video, we highlight a program called Tech Tales, a collaboration between the University of Washington, Pacific Science Center, Seattle Public Libraries, and Native American-serving organizations in the Pacific Northwest. In Tech Tales, nondominant families engage in engineering learning through storytelling, robotics, and e-textiles. At the center of the design is the recognition that all learning is cultural, and that all families and family members come to the workshop space with deep expertise around their own histories. As families animate their stories through robotics and programming through Scratch, they engage in playful and creative interactions, connecting relations and stories (stargazing, eagle relatives visiting, returning to Africa to reunite with family) with contemporary technologies (LEDs, motors, sensors), and they identify and explore new (or prior) interests while developing new competencies in multiple disciplinary forms of work (art, computer science, electrical engineering, and robotics).

Another project is Family Creative Learning (http://familycreativelearning.org/), created by faculty at the University of Colorado-Boulder. Families are invited to learn together about computing, and to interact with each other, working in teams as families and with other families. Through the experience, multiple points of learning occur, and relationships develop within the family and with other families. Common themes from the project include the shifting perspective of oneself, constructing identity, and becoming empowered. A leader’s guide supports the delivery of similar workshops worldwide. Readers are encouraged to seek more information on the project website.

Establishing Family Rules about Technology Use as a Family

Whether families use technology alone or together, research supports the value of clear communication about technology use. While we’ve discussed the ways in which technology supports family communication and cohesion, focusing on communication helps families also set rules about technology management and device use that are shared and benefit the group. Yet these rules may not come easily for everyone. As noted in the previous chapter, parents who feel more knowledgeable about the use and impacts of technology are more likely to instill guidelines or practice authoritative practices to negotiate use that is safe and reasonable. Those lacking in parental competence may either place straight guidelines without conversation or be laissez faire and not engaged around children’s use (Brito et al., 2017). Children’s own desire for and adherence to family rules around screen time and screen use will vary by age and influences from their wider social ecology. As our insight from Lanigan’s socio-technological framework indicates, family technology rules are influenced by the attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of each family member. The discussion about family rules, therefore, reflects family communication as indicative of the perspectives of each family member.

An aim of family communication is to reach shared perspectives, with guidance accommodating the needs of all. What are some techniques for doing this, specific to screen time among family members?

Let’s take phones at dinner time. For many families, meal time is the one time during the day that everyone is together. Food is shared, conversation about the day keeps everyone up to date, and there may be deep cultural or religious elements to family dinner. It’s no surprise, then, that as a society we might be concerned that phones have become a distraction during mealtime. As Turkle (2015) describes, family members are alone, together.

In 2016, Commonsense Media examined the impact of devices at the dinner table. The study surveyed 869 individuals representing families with at least one child between 2 and 17 years of age. Of that number, 807 reported having devices, 770 reported eating dinner together in the past seven days, and 362 reported using technology at dinner time. It’s notable that just half of those who ate dinner together reported using technology during that time. That may be an indicator that families were already conscientiously choosing to keep phones away. While dinner time was viewed as very important to the majority of families (61%) with devices, it was not a time when most families talked about the day. In fact, only 19% reported that meal time was used for that purpose; driving their kids in the car was identified by the greatest number. About half of those who ate together and used devices reported that it makes them feel disconnected, yet 25% reported that phones brought the family together — likely through sharing information and pictures. This report gives an idea of the complexity of an issue that could mean challenges for some families that have no rules about technology, and that for others is quite simple: when together at dinner, whether they talk or not, phones are not present.

There are a variety of tools and resources available to help families determine screen time and safe technology use and to identify common ground on technology use. One is the Family Media Plan by the American Academy of Pediatrics. This tool encourages parents and each child to identify a plan together, based on the child’s age. There is a long checklist of items that the parent and child can select jointly, then use daily to monitor the child’s use. What is the advantage to families of having this kind of checklist for self-creation of a plan? One of the Learning Activities asks you to create a media plan for three children of different ages, then compare differences in what they would do and how it reflects their development. It also encourages you to reflect on the ability of that child and the family to follow through on monitoring the actions. Yet one criticism of the Family Media Plan is that guidance is offered only for children age 18 and younger. Parents can have as much difficulty putting the phone down, or engage in practices that are distracting to others or unhealthy for themselves.

As we’ll discuss in the next chapter, self-regulation and the establishment of boundaries are new skills for adults attempting to balance work and family in this post-COVID-19, high-tech world. This family education site of a digital media nonprofit suggests eight elements that all families should consider:

- Total screen time

- Screen-free times of the day

- Screen-free family events (including dinner time)

- Not using the phone while driving

- Not using screens before or during bedtime

- Tackling habits (e.g., by silencing phones to quiet the desire to check for messages)

- Creating a family pledge

- Identifying tech-free family activities

While information and communications technology can be a distraction and create conflict within a family, research indicates its value in encouraging family communication and strengthening family cohesion. The array of applications and devices for collaboration, creativity, and communication between family members has never been greater. For many families, technology tools — especially videoconferencing — were the single strongest way of maintaining family connections during COVID-19. These connections include extended family members, and family members distant due to immigration, travel, and deployment. And videogames can be a fabulous way for family members to have fun, solve problems, and strengthen cognitive skills, and for parents to monitor children’s media exposure.

Yet as families become increasingly busy and stressed, and children adapt to newer technologies at seemingly younger ages and parents attempt to stay vigilant, it can be a challenge to use technology in ways that are meaningful and maintain family connectedness without conflict. And for still other families, as discussed in Chapter 3, the limits on resources of access, time, and money can create differences both within and across families. With other life demands, technology use has become one more focus for family flexibility and accommodation to ensure connectedness and cohesion.

- While both are 20 years older, they still play alone and together ↵