Chapter 7: Technology’s Influence on Parent-Child Relationships

Well, an element of conflict in any discussion’s a very good thing.

It means everybody is taking part and nobody is left out.

― from Harvey by Mary Chase

Chapter Insights

- Two concepts that underlie parent-child relationships: the emotional context of parenting style as the balance (or imbalance) of demandingness and warmth; and relationship dynamics as the coordination of agency/communion perspectives by parent and by child.

- Parental mediation can be active, restrictive, and indirect. Active mediation involves parent-child communication, parent engagement in media content exposure, and coordinated activity to negotiate rules.

- A variety of factors related to the parents (e.g., mediacentrism), the child (e.g., age) and the context (e.g., COVID-19 pandemic) can affect parent behavior on regulating children’s use.

- Reverse mediation, or when children’s knowledge of technology exceeds parents’ and enacted to aid the parent’s use, can be a potential conflict in the relationship.

- Conflict in the parent-child relationship might occur in several ways related to technology (e.g., through parental attempts to control technology use, negotiations on content).

- Differences exist in perceived conflict in families by child age (e.g., fewer parents report conflict with children under 8 years), and changes in parent control with age. Influences on parental control can relate to the child’s advancing development (e.g., confidence, knowledge of child’s actual use, ability to stick with plans).

- Potential conflict to the parent-child relationship, to parenting, and to the child’s well-being can occur through the parent’s own technology use while with the child. Distractedness (or “technoference”) has been related to a variety of parenting consequences.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

The Parent-Child Relationship

Relationships between parents and children are key to family well-being: as a vehicle to “successful” parenting, which means healthy child development; in the ongoing happiness of children and of parents; and in overall family satisfaction. The dynamic between parent and child is a reciprocal, emotional context through which information is communicated that guides the child’s understanding of themselves and the world; through which the parent expresses their knowledge, experience, goals, and dreams for their child; and through which the parent develops (Azar, 2006; Harach & Kuczynski, 2005). And as parenting is a social role, one conferred with certain responsibility and expectation by the society and culture in which the family lives, the relationship with the child may be viewed differently. Some may view the role with more authoritarian rights; others may view the child’s agency as a vehicle for expression that calls for a more democratic, authoritative approach (Bornstein, 2012). And some may be so overwhelmed by society’s demands and challenges that they view the role with near resignation and give authority to the child to determine their path.

And each parent-child experience is different. As we viewed Belsky’s multiple determinant model in Chapter 6, we saw how parents’ perspectives change with experience, age, gender, socialization, and developmental history. Their interactions also depend on unique characteristics of the child. And the social context factors heavily on the parent-child dynamic, particularly as support is available to buffer stressors. In short, each relationship between a parent and child is like no other. It is forever in the life of the child, and it changes over time and with changes that occur in the lives of the parent and of the child. This transactional, developmental, contextual consideration of the parent-child relationship over time has led scholars to call for using a life-course perspective when characterizing the enduring nature of the unique human experience as facilitated by technology (Dworkin et al., 2019; Shin et al., 2021).

In previous chapters we’ve gleaned the systemic, ecological, and biological forces on individuals in families and on family member subsets, and understood technology as an external force that influences the family through facilitating communication, aiding family life, and at times introducing conflict through differences in the ways that family members use technology. In Chapter 5 we understood the many ways technology can impact all domains of children’s development — cognitive, social, psychological, and physical — and differences in use and impacts as children age from infants through young adults. In Chapter 6 we reviewed basic functions of parenting that emphasize the physical health and well-being of the child (keeping the child safe and thriving); guiding the many social, emotional, cognitive, and physical aspects of the child’s development; and at times being an advocate for the child. We saw that technology could support the parent’s role in childrearing — primarily as it supports the parent as a vehicle to social and informational support, and as an expression of the parent’s identity. We also introduced other ways that parents use technology in the parenting role — with their children, and with technology as the focus of their parenting.

In this chapter we take a closer look at these dynamic elements of technology in the parent-child relationship, including how parents enact their role in childrearing through parenting about technology. Parents mediate, monitor, and moderate children’s use, and in keeping their children safe and their technology use effective, parents also model ways to use technology through their own behavior. Parents mediate, monitor, and moderate children’s use, and in keeping their children safe and their technology use effective, parents also model ways to use technology through their own behavior. Yet there are certain “paradoxes” that affect technology’s application to the parent-child relationship (Hessel & Dworkin, 2018; Jarvenpaa & Lang, 2005). For example, we see that generational differences in exposure to technology, comfort and skill in use, and motivations for use can create a shift in a relationship’s power dynamic. This may result in friction between parent and child. This chapter will explore those possibilities and recommendations for peaceful negotiation.

This chapter will also look at technology use as it positively facilitates and influences the quality of parent-child relationship. Applications like FaceTime, texting, and social media are used to maintain communication and feelings of connectedness between parent and child, and can promote feelings of cohesion. This can be seen by the time college students spend texting or making video or voice calls to their parents while away (Vaterlaus et al., 2019), and in the heavy use of videoconferencing between parents and children, and grandparents and children, during COVID (Hamilton, et al, 2021). Indeed many parents and children are quite positive about having mobile devices as a means for continued family contact. Media multiplexity theory posits that when a “repertoire” of technologies are used, the relationship is closer (McCurdy et al., 2022).

Yet relational use can also mean the nonverbal communication that comes when a parent or child ignores the other, distracted by technology. Sadly this is an all too real scenario that can disrupt quality in the relationship. Studies suggest that parental distraction by technology can compromise secure attachment and, consequently, child development (Kildare & Middlemiss, 2019; McDaniel, 2019). Parents can also overshare online, much to the embarrassment of the child (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017). These elements of technology and the parent-child relationship are explored in this chapter.

Finally, analysts of the existing literature identify both assets and challenges of current technology and the ways in which they are used to facilitate the parent-child relationship (e.g., Shin et al., 2021). The chapter closes with their observations and questions to move us forward in this important family topic.

Parenting Frameworks

To set the stage for a deeper understanding of the parent-child relationship dynamic, we’ll explore two parenting frameworks. One is a frequently used construct of the parent’s style of communicating which offers an emotional context for the relationship. The other is less well known, yet presents the balanced perspective of both actors in the relationship and the balance required for connection.

Parenting style

Parenting style is frequently studied as the emotional context through which parents assert authority or invite children’s input while guiding children’s behavior (Darling & Steinberg, 1993, 2017; Smetana, 2017). Because of this, parenting style has been conceptually and empirically related to measurable elements of childrearing, such as demonstration of support, relational depth, and parent–child conflict (Aloia & Warren, 2019), which in turn contribute to myriad child outcomes (Smetana, 2017).

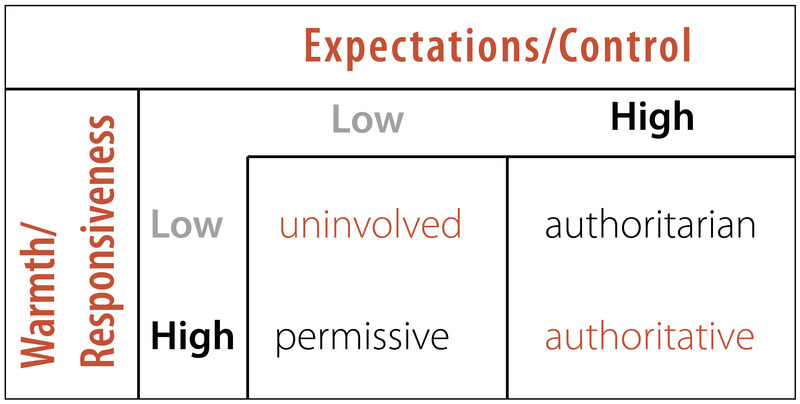

Baumrind’s (1971) parenting style construct uses demonstrations at the intersection of warmth and demandingness as indication of authoritative (balanced), authoritarian (high demandingness, low warmth), permissive (low demandingness, high warmth), and neglectful (low demandingness, low warmth) childrearing. Contemporary perspectives on Baumrind’s construct encourage adaptations through a cultural and contextual lens, and consideration of factors such as parenting beliefs that moderate demonstrations of style (Smetana, 2017). More domain-specific applications have been suggested which are sensitive to the interplay between parent’s goals, child’s needs, and parenting processes.[1]

Examples of parenting style and parental mediation have found, in general, that those who are more permissive (higher in warmth over control) are less likely to restrict children’s screen time, while those who are more authoritarian are more likely to do so. In a 2009 study, Bumpass and Werner explored types of parental technology regulation. They studied 113 children in 3rd to 6th grades and 109 mothers, identifying four clusters based on rules, enforcement strategies, consequences, and child adjustment. Traditional mothers reported rules related to time, permission, and co-viewing. Technology-specific mothers used blocking software, filtering, and removal of privileges. Passive mothers voiced rules that required only minimal parental supervision, and they were more watchful of the child’s interest. And the children of parents with few rules (e.g., neglectful) reported slightly higher levels of internalizing problems such as depression and anxiety, and demonstrated slightly lower levels of prosocial behavior.

Wartella et al. (2013) found a parallel between parenting style and family media practices. Looking at families with children between birth to 8 years, those in mediacentric households (reporting approximately 11 hours or more per day) were more permissive than those who were media moderate or “media light.” Children in mediacentric homes are also more likely to have televisions in their bedrooms.

As demonstration of the complexity of applying the parenting style construct to the parent-child relationship with technology, a study of 504 parent-teen (12–17 year old) pairs proposed a model linking parenting style, online relational behaviors, and relational quality (Aloia & Warren, 2019). The researchers hypothesized that parental behaviors such as sending comforting messages and sharing material would mediate (i.e., be a conveyor for) parenting style and parent-child relationship quality including parent-child conflict and relational depth. In fact, although they validated previous research linking parenting style to relationship quality (e.g., enhanced parent-child conflict with authoritarian or permissive parenting), they found no relationship between parenting style, online relational behaviors by the parents, and relationship quality. Authoritarian parenting showed no relationship to any of the online strategies (comforting messages, material sharing, planning behaviors), and authoritative parenting showed positive and significant relationships to all three, yet permissive parenting also related significantly to two of the actions (comforting messages and material sharing). Planning behaviors and positive messages online were positively related to parental comfort, yet planning behaviors and material sharing were also related to perceived conflict. The authors observed methodological limitations (e.g., data from self-report) as a cause for the unexpected result, but also suggested that, with regard to mediated communication channels, parents and children may develop unique norms (p. 53). As Dworkin, et al. (2019) observe,

“The insurgence of technology has completely changed the family landscape, challenging what we know and requiring a reassessment of how we understand family relationships during adolescence, a time when technology acquires new meaning for developing and maintaining interpersonal relationships. (p. 514).”

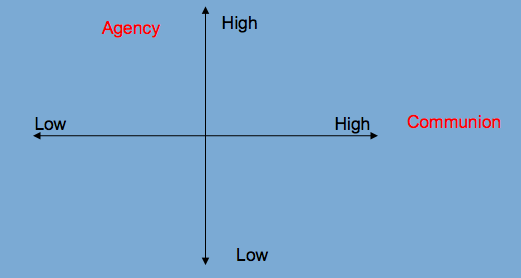

Agency and Communion

Facilitating the child’s well-being related to technology through and while maintaining a positive relationship with the child is no small feat for parents. In promoting the child’s development, the relationship must be a balance of agency and communion by both individuals: assertion of the parent’s power while keeping in mind communion with the child; promotion of the child’s agency and independence, while keeping in mind the relationship. In promoting the child’s development, the relationship must be a balance of agency and communion by both individuals: assertion of the parent’s power while keeping in mind communion with the child; promotion of the child’s agency and independence, while keeping in mind the relationship. Unlike parenting style, which assesses the actions of the parent, perspectives of agency and communion regard both actors in the relationship (Heck & Pincus, 2001; Wiggins, 1991). Each person, in interaction with the other, asserts an action reflecting dimensions of both coordinates. Conflict arises when both are seeking agency (or power) more than communion. As related to parent-child relationships, conflicts occur with both child noncompliance and resistance to parents requests (high agency/low communion) and with parent resistance to children’s requests (high agency/low communion) (Eisenberg, 1992).

For example, if my partner and I are deciding on a vacation location, and I want to go to the mountains and they want to go to the beach, as we both assert our agency (power) in our desires, we compromise the value of communion (joint happiness). We are at a standstill and our relationship suffers. If, however, through discussion, we listen to each other about the interests of the other with a true value for the relationship and we come to compromise, we are more balanced in our individual agency and communion. Within the parent-child relationship, the parent’s actions are tempered by understanding the developmental age and ability of the child, and changes in that development over time (Heck & Pincus, 2001). Agency by the parent is, in part, a personal expression of fulfilling the responsibilities of childrearing. The joint balance of agency and communion between parent and child in negotiation and understanding is within this structure of safety and growth.

The ecological context is a consideration for both parent-child relationship models when applied to new media and digital technology. As observed in previous chapters, interactions and dynamics of the relationship are influenced by ecological contexts of the microsystem of the family, and by exosystems, macrosystems, and chronosystems. These systems create influences on the development of both the child and the parent, and on the conditions in which the family lives. Technology access and use and qualities of the devices and applications are external and inherent influences in each of the systems that can both facilitate and challenge relational dynamics (Navarro & Tudge, 2022; Lanigan, 2009).

Parental Mediation and the Parent-Child Relationship

Fully 98% of parents in a recent U.S. study believe it is the parent’s responsibility to protect children from online content (Auxier et al., 2020), compared to 65% expecting the government or technology (78%) companies to bear responsibility. While most parents (71%) are aware of and concerned about the amount of time children 11 and younger are spending with screens (Auxier et al., 2020), more (84%) report feeling confident that they know how much screen time is too much. Most (71%) believe that widespread use of smartphones might be harmful to their children’s socioemotional learning. There is also concern by most about exposure to online predators (63%), sexually explicit content (60%), and violent content (59%). While bullying is a general concern of many parents, the majority (96% of parents of children 5–11) report that their child has not been bullied online (Auxier et al., 2020).

As parents assert their responsibilities to keep children safe online and guide their development, potential areas of conflict include:

- Parental attempts to regulate use.

- Parental concern over potentially negative consequences of internet use that can lead to over-restrictions on use.

- An imbalance of power as expertise in technology use varies between parent and child.

- Counter modeling of technology by parents’ own use (e.g., do as I say, not as I do)

- Parent invasion of children’s online social space.

The majority of families don’t perceive significant conflict around technology. Parents of young children (birth to age 8) don’t perceive regulating children’s technology use to be a conflict (Wartella et al., 2013). Even parents of older children (8 to 18 years) don’t report significant struggles. In a 2016 Commonsense Media report, nearly two-thirds of parents (62%) disagreed that getting a child to turn off their smartphone or tablet was a struggle. The majority (85%) agreed that monitoring child safety was important, and nearly the same amount (81%) disagreed that the child was less likely to communicate face-to-face. That said, parents of boys and of those children with lower grades did report greater struggle. Similarly, a 2018 report of families in the European Union also determined that most do not report conflict on technology use (Livingstone et al., 2015).

In large part, there is optimism that the lack of conflict observed in families is the result of technology oversight integrated into parenting practices and the parent-child relationship. Technology and adolescence researcher Candice Ogders (2018) observes,

Because online problems can be largely predicted by young people’s vulnerabilities offline, much of our existing knowledge about what promotes healthy child development is applicable even in what seems like a foreign digital landscape. Strategies such as the maintenance of supportive parent–child relationships that encourage disclosure, parental involvement in the activities of their children, and the avoidance of overly restrictive or coercive monitoring will help to support adolescents and keep them safe online, just as they do offline.

In the next section we explore types of mediation practices in families, and the potential for conflict, and the opportunities for parent-child communication.

Mediation practices

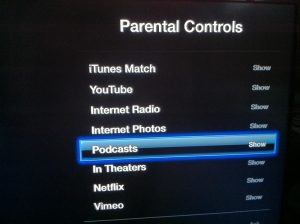

Mediation practices vary by type and family (Rudi & Dworkin, 2018). Frequently, mediation practices are labeled as active or “enabling” (of positive technology use) or restrictive. A recent qualitative study with 40 parents of Australian teens (Page, 2021) identified five mediation strategies, three of which were active: physical observation, digital surveillance, and trust-based and discursive strategies; one restrictive: restriction and control through social or technical means; and one (as alluded to in Chapter 6), indirect: talking with other parents. Parents’ active mediation occurs through direct parent-to-child interaction and conversation about media’s effects. Co-viewing or co-participation (such as playing games) enables parents to actively mediate and monitor children’s exposure and scaffold healthy use. More restrictive mediation means setting rules regarding the time spent or content viewed. It can also mean “e-rewards,” in which parents withhold or grant technology use in recognition of good behavior. More restrictive mediation means setting rules regarding the time spent or content viewed. It can also mean “e-rewards,” in which parents withhold or grant technology use in recognition of good behavior. Across the approaches, restrictive mediation can reduce negative media effects, and co-viewing or “enabling” can enhance or facilitate media’s positive effects (Coyne et al., 2017).

The EU Kids Online report (2020) surveyed children age 9–16 years in 19 countries. An average of 33% said their parents actively talk to them about the internet, 30% said sometimes, and 37% said never. Across countries, on average, higher percentages of children at younger ages reported parent discussion about the internet “at least sometimes:” 67% of 9–11 year olds, 61% of 12–14 year olds, and 54% of those 16 and older. When asked about active mediation strategies by parents, friends, and teachers, the highest percentages were reported for parents (e.g., 64% reported that parents “help me when something bothers me on the internet,” compared with 45% friends and 35% teachers). Internet safety is a common topic of mediation, with 85% of EU children reporting that their parents talk about this. More technical controls are far less frequently reported (22%, on average, report parental control through GPS monitoring, use of software that blocks or filters internet content, or tracking applications) . Also, a minority of children — about 15% — reported restrictions on using a web camera, downloading music, or using social media. That said, there are very clear differences in social media use restrictions by age, with the majority of children age 9–11 indicating that they cannot use social media.

The resolution of “conflict” with mediation is more nuanced than might be believed. Recent research with Australian families of teens revealed the range of ways that parents negotiating technology use with their teenagers (Page, 2021). Traditional mediation strategies may be used, but when they are not successful parents turn to other strategies, such as trust-based and discursive (reasoned negotiation) ones. Similarly, in interview research with pre-teen and teenage children (n=23) and their parents (n=18, Blackwell et al., 2016), children expressed the desire for shared expectations, rather than more attention to the issue of technology. They claimed that parents primarily told them what not to do, and didn’t have a very accurate perception of either the quantity or quality of their screen time, or its effects on them. The interviews unlocked a more complex dynamic than of parents establishing rules and children breaking them. They identified a give-and-take in negotiating family life, in which children’s needs and desires for technology use are taken into consideration, and reflect nuance — for example, when “rule violation” is acceptable. The authors concluded that families respect the developing teen’s need for privacy and independence, while maintaining consistent and realistic expectations around work, attention, and the interests of the whole family to better manage household technology use.

Influences on parental mediation

Age of child

Parental restrictions on children’s technology use largely curve with the child’s age — with monitoring occurring through co-use in early childhood and middle childhood, then tapering off through adolescence.

Naab (2018) refers to early childhood parenting mediation as “trusteeship,” as the cognition and communication skill limitations of the very young child confer responsibilities on the parent to oversee their access and safe use as they make the transition to mediating children’s own active, independent use. Co-viewing with young children appears to be predominantly through traditional media including books, TV, smartphones, and tablets, and less so with games (Connell et al., 2015). As an indication of the blend of parental agency in the role and accommodating a child’s need, some parents may use media to soothe babies who are fussy and demonstrate poor self-regulation. Mediation with school age children can be restrictive (limiting use of hardware or software, including taking away technology as a punishment), monitoring (tracking use, messages, and the child’s location), and active (talking to children about their technology use) (Auxier et al., 2020; Blum-Ross et al., 2018; Livingstone et al., 2015).

Parents’ conversations with their children about the content of their media also varies by child age. In Commonsense Media’s 2016 study of parents and their teens and “tweens,” parents were more likely to talk with their 12–14 year olds about media content while watching television, viewing apps on a device, using a computer for something other than homework, and playing videogames than with their teenagers; only when it came to social media did parents report higher frequencies of discussing content with children. Coyne et al. (2017) observe that research has yet to determine the interplay between parents’ mediation strategies and more specific child characteristics.

Family demographic differences

Parents’ education, income, gender, and age may influence mediation. Parents who are higher in income and educational attainment and who demonstrate more comfort with technology may exercise more mediational practices. Livingstone et al. (2015) determined socioeconomic differences in mediation strategies and attitudes in a sample of parents of primarily 4- to 7-year-old children in seven countries, including England, Finland, and Russia. Families with less income, formal education, who are non-White, and whose parents measure higher on depression are more likely to report higher rates of media consumption. When surveyed, many parents note that media provides a safe, inexpensive, and available form of entertainment for their children (Livingstone et al., 2018). Similarly, Wartella et al.’s (2013) observation of permissive parenting style and mediacentrism, noted earlier, also showed demographic correlations. Parents who were lower-income and single reported greater consumption of media in the household than those with other demographic characteristics. Media was reported as a favorite family activity, and mothers were more likely to report using it as a parenting tool (e.g., keeping a child occupied and safe while she attended to other duties). It should be noted, however, that in a U.S. sample Connell et al. (2015) found scant relationships to co-viewing with young children by parent education level or race. Parents in the EU with more education and income used a diversity of mediation strategies and encouraged non-school media use for learning. Cross national variation in parent mediation strategies has been found among the Finnish (actively engaged), Czech (passive), and in EU and UK countries and Russia (restrictive) (Helsper et al., 2013).

Mothers are more likely to demonstrate mediation than fathers (Connell et al., 2015; CSM, 2016). In their research among Portuguese school-age children, Ferreira et al. (2017) identified not only parent gender differences in mediation by type of activity (e.g., fathers actively mediating children’s use while playing videogames), but gendered perspectives by children of parents’ technology mediation. Children perceived fathers as more skilled in using technology, reported that their technology was for work (vs. mothers’ devices that were to be shared), and that the father’s mediation was more technical (e.g., uploading, removing software) and mother’s more digital (e.g., exposure to content quality).

Parents’ technology use, comfort, and skill

Parents’ mediation strategies appear to relate to their attitudes toward technology, their competencies, and their own use, as observed in research in EU countries (Brito et al., 2017; Livingstone et al., 2018) and research in the US (e.g., Commonsense Media, 2016; Wartella et al., 2013). Observing the construct of reasoned action applied to technology acceptance (Ajzen, 1985), Nikken and Opree’s (2018) survey of parents of young children (ages 1–9) in the Netherlands identified basic proficiency associated with the ease of active co-use. Advanced and basic proficiency with technology related to restrictive mediation, and advanced proficiency related to imposing technical restrictions. As Naab (2018) observed from in depth interviews with 29 parents of young children, parents are often uncertain about digital strategies and gain proficiency over time through interaction with their child, acquisition of knowledge about technology’s affordances and challenges, and their own comfort with the interplay between themselves and their child’s needs.Parents are often uncertain about digital strategies and gain proficiency over time through interaction with their child, acquisition of knowledge about technology’s affordances and challenges, and their own comfort with the interplay between themselves and their child’s needs.

Parental use can influence the effectiveness of their mediation strategies. In the Commonsense Media study with over 1100 parents in 2016, parents spend more than 9 hours a day with screen media (especially personal media like smartphones) . A majority (78%) believe they are good media and technology models for their children. Yet research with parent-teen pairs indicates that when teens see parents’ time on their phones similar to their own, they question parental advice and role modeling (Commonsense Media, 2016; Livingstone et al., 2018).

Child guidance and the power differential

The picture of parental mediation can get complicated as a generation of children grow up with technology in ways far different than those of their parents, and a potential power dynamic is shifted. Livingstone et al. 2018 observe this particularly in lower-income and immigrant homes, as children gain more comfort and skill with technology than their parents (Livingstone et al., 2018), or when children need to assist parents with language translation and technology. Perhaps this is why teens don’t turn to parents for safety issues related to technology (Blum-Ross et al., 2018; Commonsense Media, 2018), or for information on sexual health. Flores and Barroso (2018) identified SES differences in parental technology comfort and use and the ability to talk to their teenagers about sex. Limited knowledge of how technology works, including realities of peer communication, privacy issues and laws, and the potential for exposure to imagery, act as barriers to parental communication that supports the child’s sexual health.

Various scholars have characterized this complicated parent-child power dynamic (Dworkin et al., 2019). Livingstone across 19 countries, on average 40% of 9–16-year-olds report often or very often helping parents when they found something difficult online, and 29% sometimes helping parents. This differential in knowledge can upset the traditional family hierarchy. (2009) refers to tech-knowledgeable children in the household as “youthful experts,” while Katz (2010) calls them ‘media brokers.’ Correa (2014) labels the knowledge sharing as “bottom-up technology transmission,” and the EU Kids on the Internet 2020 report calls this “reverse mediation.” The latter reports that, across 19 countries, on average 40% of 9–16-year-olds report often or very often helping parents when they found something difficult online, and 29% sometimes helping parents. This differential in knowledge can upset the traditional family hierarchy. In interviews with parent-teen pairs in 1995, Kiesler et al. (2000) determined that fathers’ attitudes prevented them from seeking help from their children about internet-related issues; the fathers voiced concern about a shift in their parental authority.

In a later study with Belgian parents and teens, Nelissen and Van den Bulck (2017) predicted that reports of conflict would correlate with parental requests for assistance with technology. The survey included questions like “Do you ever get into an argument with your child/with your parent about (a) television use, (b) tablet use, (c) smartphone use, or (d) computer/laptop use?” It used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “(almost) never” (=0) to “(almost) always” (=4). With regard to media guidance, the pairs were asked “If you think about your children, how often do they teach you to use the following media, technologies, and/or applications?/If you think about your parents, how often do you teach them to use the following media, technologies, and/or applications?” Again, a 5-point Likert scale was used and applied to 13 technologiesm including smartphones, online purchases, and tablets. After controlling for demographic variables (including parent and child gender and age), there were significant associations between a parent help seeking/guidance by children and parent-child conflict. The authors observed that child guidance was dominant on some technologies — smartphones and specific apps — but not all.

An example of context as influence on parental mediation: The COVID-19 pandemic

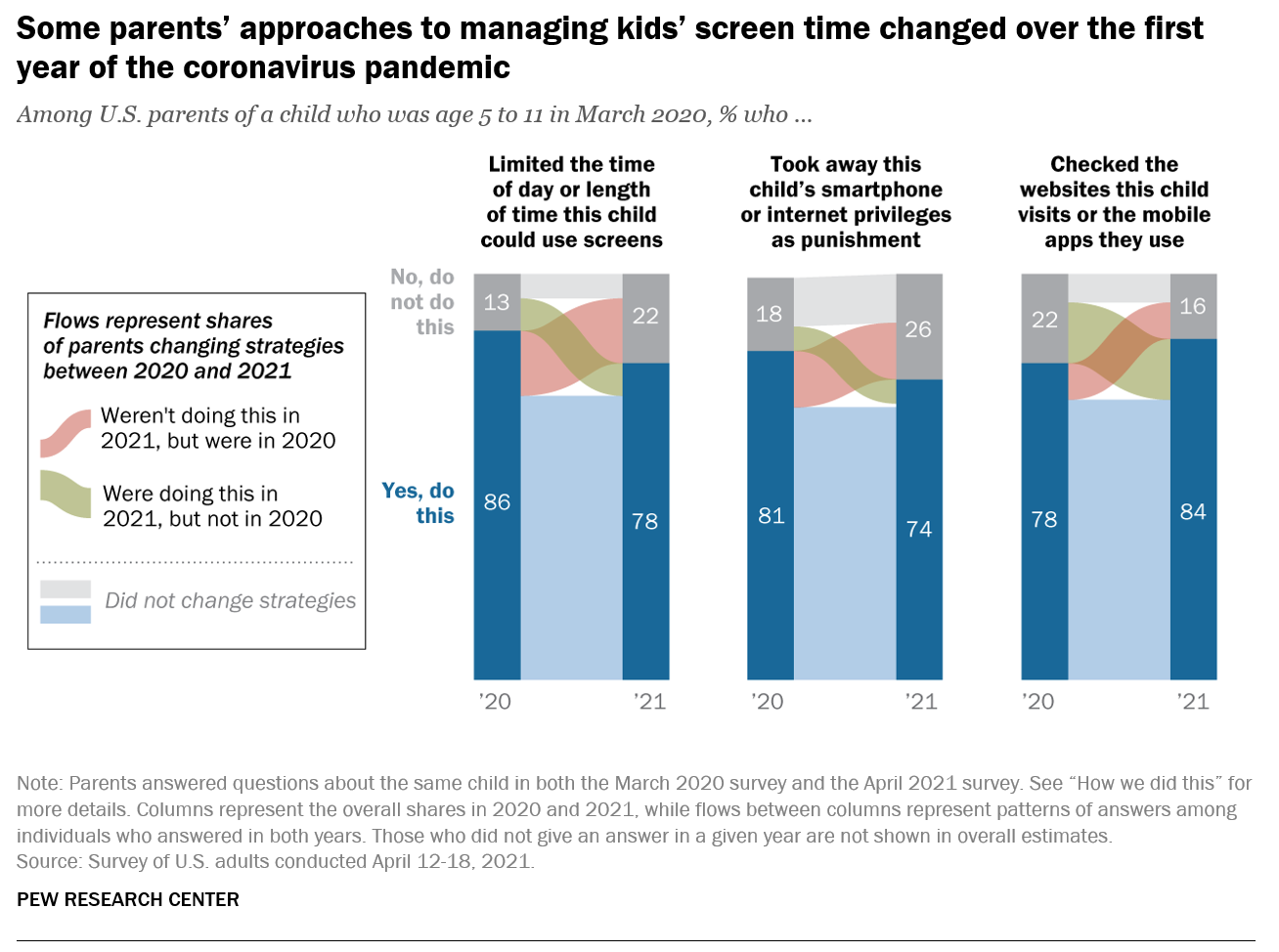

When conditions encourage children’s technology use, parental mediation can shift. Clearly, the COVID-19 pandemic was an influence. As their children connected with friends, attended school, and sought out hobbies online during isolation and quarantine, parents’ efforts to mediate children’s screen time changed. As a report by Pew (2021) indicates, fewer parents reduced children’s time on screens and took away children’s smartphone privileges. On the other hand, more parents were active in checking children’s exposure online, and parents’ beliefs that their children spent too much time online nearly doubled. Among parents of children 11 or younger, in 2020, 28% felt their children spent too much time on their phones. In 2021, that percentage climbed to 42%. (See figure below).

With regard to older children, parents reported that, during COVID, connections through videoconferencing, and with resident children through gaming and time spent together, deepened personal relationships (Joyce et al., 2021).

Technology’s Role in Parent-Child Communication

The primary reason that parents secure phones for their children, even before age 12, is to communicate with them (Auxier et al., 2020). Through texting and through voice and video calls, parents can convey information to children that supports their development, enable coordination, and promote closeness. The efficiency of using ICT for communication also makes co-parenting relationships easier, such in the case of divorced and separated parents (Ganong et al., 2012; Saini & Pollack, 2018), and maintains parent-child connections during separations, including military deployment (Carter & Renshaw, 2016) and immigration (Casmiro & Nico, 2016; Karraker, 2015).

Shin et al.’s (2021) literature review on technology designs that foster the parent-child relationship identified factors indicative of family qualities and technology-specific conditions. They include:

- reciprocity in the family,

- reinforcement of transparency,

- affection and trust,

- physical proxy of each other through an object or interface design,

- accessibility, level of technology sophistication and communication resource, and

- enjoyable, age-appropriate shared content between parents and children, and situational awareness and routine.

When parents and children are at a distance, system design that favors media richness (closer approximation of real life) and synchronicity, and the ability to maintain privacy, are positive. Challenges to the parent-child relationship occur through discrepancies in expected communication between parent and child(ren), through parents’ complex emotions toward parenting due to their busy schedule, and, from the technological standpoint, from access limitations. As this section of the chapter indicates, the use of technology as a means to facilitate parent-child relationships is quite a complex issue. Although there are elements specific to digital media and the programming of the for communication and interaction, challenges arise through human factors inherent in the individuals and their relationships.

Connections, for example, may not always be smooth, and whether due to technology or the actor, complications can arise. Use of technology to maintain the parent-child relationship may lead to what Parrenas and Boris (2010, as cited by Karraker, 2015 p. 13) refer to as the “antithesis of intimacy.” Expectations for maintaining communication through the ease afforded by digital media can impinge on children’s or parents’ independence. Connections, for example, may not always be smooth, and whether due to technology or the actor, complications can arise. The complicated power dynamics discussed above can and do interfere with satisfaction when using technology for parent-child communications. And although teleconferencing made parent-child visits possible during COVID-19 for those facing separation due to welfare issues, technological and human barriers prevented this alternative to in-person visits from being successful (Goldberg et al., 2021).

Shin et al. (2021) observe developmental differences reflected in the availability of technology and use by parents and children that affect satisfaction. For young children, technology that is playful, age-appropriate, and encourages creativity can foster engagement by both parent and child. School-age children and their parents have a strong desire to be together, learn more about each other, and feel a sense of warmth and security. Yet designs may not be user- or communication-friendly, and differences in ability and access can create barriers to effective use. For older children (e.g., adolescents), when parents and teens have access to phones and social media, and when a common time for interaction is apparent, communication appears effective. Yet as Dworkin et al. (2019) observe, the paradox of connecting and distancing can make parents’ use of social networking and unscheduled calls feel intrusive and like a privacy invasio.

Assets and challenges are apparent for specific populations of parents and children as well. Parents and children attempting to maintain communication through technology across legal separations face particular scrutiny with regard to child privacy and safety (Saini & Pollack, 2018). In a survey with 106 family caseworkers, Saini and Pollack (2018) identified that the majority of legally separated parents and children use technology to maintain communication. This can be quite positive, as they can each keep abreast of the life details of the other and maintain connectedness, particularly when a child is long-distance and living in the other parent’s home or in a foster home. Caseworkers also saw it as a way to protect the child from conflict in the parent-to-parent relationship, and enhance the child’s feeling of safety. Yet rampant posting on social media diminishes the child’s safety, as well as the privacy of the parent who may closely monitor and track the child. As with other cases representing the range of technologies’ uses and affordances, the picture is a complex one. Because of this, the caseworkers in Saini and Pollack’s study advocates for ICT not as a replacement for parent-child connections, but as a way to enhance communication.

Possible disruption in the relationship: Parents’ own technology use

As noted above, parents’ own technology use is a significant factor in their attitudes about monitoring and mediating children’s use, and in shaping and modeling children’s technology consumption. Samual’s (2017) counter response to the argument that smartphones were destroying a generation (Twenge, 2017) was that smartphones distracted parents, leading them to demonstrate “minimal parenting.” McDaniel’s (2019) and Kildare and Middlemiss’ (2017) reviews of the literature concerning parents’ use of technology when with their children paint a third picture of communication in the relationship: that of nonverbal messaging through distracted use. Noting that the majority of research in this area has focused on parents of young children, McDaniel observes the many reasons parents would use their phones with a child present. Not only do they seek information and communicate with others, seek emotional support, or continue work, but their use attempts to relieve the boredom of childrearing. This “technoference” (McDaniel’s term for the “everyday intrusions and interruptions of devices in our face-to-face interactions”) can have potentially serious consequences to the child through the parents’ ability to connect and engage and through the child’s own observation of the parent’s distracted action, and can negatively impact the parent’s own emotional state. Parenting outcomes of being distracted by one’s phone include reduced verbal and nonverbal interactions with the child, reduced awareness and sensitivity to the child’s needs and responses, and reduced coordination and communication in co-parenting. McDaniel, and Kildare and Middlemiss, note that these responses are directly associated with the relational mechanisms in attachment formation, although longitudinal research to date hasn’t validated these assumptions.

Additional parenting consequences of being distracted by technology include the difficulty of multitasking between the device and the needs and attention of the child, and time displacement (e.g., focusing on a phone compared to active time with a child). From the child’s perspective, they may express dissatisfaction in the time spent with the parent and in turn, feel ignored. Kildare and Middlemiss cite a study in which 32% (of 6,000) children reported feeling unimportant when their parents were distracted by a phone. As the authors of both review articles observe, more research is needed to more definitively understand specific dimensions of parental technology use with children (e.g., how much time is spent on phones when with children, specific activities parents do while on their phones) and impacts on parenting, the relationship, and child development. They also observe that it’s not reasonable to expect parents not to engage with technology when with their children, observing the complex reasons that parents use technology. They advocate for education on appropriate use, and engagement in ways that are healthy for the relationship and for the child. This resource from Zero to Three offers parents ways to focus on their children, not their phones.

“Sharenting”

As discussed in Chapter 6, parents express their caregiver and relational identities online through blogging, posting on social media, and texting ideas and images of the children to others (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017). A challenge can occur in the parent-child relationship when children object to their images and information about themselves being shared, particularly without permission (Saner (2018) refers to this as a “permanent digital tattoo”). While not as overt an expression of distraction by technology use as those discussed above, “sharenting” can still send a message to the child that their feelings are not being considered. Blum-Ross and Livingstone (2017) determined that when parents of younger children share images and experiences of their child and childrearing, they may also have misgivings about the archival nature of the internet and the possibility of their posts resurfacing when the child is older. Parents also express a certain element of guilt, part of the complex feelings parents describe, as discovered in Shin et al. (2022)’s review of the literature of parent-child relationships through technological innovation. Parents hold an awareness of the child’s aging to the point of awareness and expressing feelings of dissatisfaction with their private information being shared. Blum-Ross and Livingstone share this incident, which directly points to the potential conflict with “sharenting” and the need for parent-child communication to maintain communion:

Harvey confronted this issue when his 6-year-old son Archie began to express discomfort at appearing on the blog. Harvey described how Archie had begun to ask what the photos Harvey took were for, questioning “is this a photo for you, Daddy, or is it a photo for the blog”’ Increasingly Archie would refuse to be in pictures, eventually exacting revenge by covertly using Harvey’s phone to post an unflattering picture of Harvey eating a sandwich on his dad’s Instagram feed. Harvey was working with Archie to help Archie decide what “he wants me to write” so he could be more in control. Yet, finding himself cajoling his son, Harvey described a struggle between respecting his son’s boundaries and keeping his commitment to the blog and his readership among the wider blogging community. (Blum-Ross & Livingstone, 2017, p. 116).

Focus on technology-facilitated parent-child relationships in young adulthood

A significant amount of research has examined the role of technology in the parent-child relationship during young adulthood. One conclusion is that the availability and use of ICT is a positive influence on this relationship. A review by Hessel and Dworkin (2018) identified differences in how young adults use technology to communicate with parents, compared with siblings and grandparents. The authors indicated that when children go to college (given that college students are an often sampled group in this research area), there may be a stronger focus on the relationship, and technology has an intentional purpose. While they indicate that the research on persons other than parents is limited, young adults appear to use a variety of methods to maintain relationships with parents through technology, including adding parents as “friend”’ on social media, texting, and sending email (though the Hessel and Dworkin review and McCurdy et al.’s 2022 research with college students validates that email use has declined). Purposes include utility (sharing, asking for help), immediacy, and emotional connections. Relationship quality appears to be positive, as demonstrated by emerging adults’ reports of satisfaction, feelings of intimacy, and the number of types of media used for communication.

As an example, Vaterlaus et al. (2019), surveyed 766 young adults and adolescents (just over 10% of the sample)Young adults’ reports of using computer-mediated communication with parents (particularly text messaging when it came to both mothers and fathers) were significantly associated with feelings of closeness, togetherness, and connection in their time spent with the parent. and their parents on their use of technology together and on the notions of quantity and quality time spent. Not surprisingly (given that the young adults were away and in college), teens reported spending more time with their parents. Among the whole sample, there was a clear perceptual difference between quantity time and quality time. Young adults still sought and identified having quality time with parents. Type of media was differentiated when considering connectivity: synchronous media such as telephone calls, video chat, and texting facilitated quality interactions; fewer young adults reported using email, social networking, and texting for quality interactions. And young adults’ reports of using computer-mediated communication with parents (particularly text messaging when it came to both mothers and fathers) were significantly associated with feelings of closeness, togetherness, and connection in their time spent with the parent. The authors observe the role that technology can play in maintaining quality relationships between parents and teens, and acknowledge the challenges brought about through an individual being distracted by media when in the presence of the other. They recommend additional research and educational efforts on the benefits of using technology together in ways that foster and facilitate relationships.

Yet Hessel and Dworkin indicate that a dominant theme in the literature indicates potential challenges with autonomy, or rather the lack thereof. Frequency of contact with parents and parental over-involvement related to lower feelings of autonomy, whereas those with a strong parent-child relationship reported higher levels of autonomy. They also observe that, as noted in Chapter 5, there are differences by generational cohort, as research with college students just two years apart indicates differences in email and social networking behavior with parents.

McCurdy et al. (2022) also point to differences in communication behavior and perceived young adult/parent relationships. In interviews with 44 college students, those who used a rich communication repertoire for connection with their parents reported more closeness. Citing media multiplexity theory, the authors identified that students perceived stronger relationships due to multiple technologies affording more contact frequency, more ways to make connection, and a stronger parental social presence. Interestingly, young adults also were strategic about differentials in technology competence and access by their parents to maintain boundaries. Knowing what skills their parents had, and which applications they did and didn’t use, worked to their advantage as ways to find necessary separation for their individuation. From Miller-Ott et al.’s (2014) research, frequent texting, establishing rules around availability, repetitive contact, and relational arguments were more direct strategies for healthy individuation with connectedness.

Research also suggests new opportunities for connecting with parents: gaming, social media, video creation, even family genealogy applications. Given the range of potential technologies for interaction and differentials in access and use together, Hessel and Dworkin (2018, p. 369) wisely observe,

Rather than building research around specific technology, such as Facebook, categorizing technology options by context will produce findings that are more transferable and durable. Using theoretical foundations such as Media Richness Theory may help to identify which technology choices complement which types of communication between which family members for what purpose.

Conclusion

This chapter reveals complexities in the notion of the parent-child relationship and technology. Most families don’t perceive conflict, though when the focus of research, perception may be skewed depending on who is being interviewed. Positively, many children and parents manage negotiations around children’s healthy technology use, and parents practice active or other types of mediation that encourage children’s positive use.many children and parents constructively negotiate healthy technology use, and parents practice active or other types of mediation that are encouraging and maintain trust and communication in the relationship There isn’t a need for practices that are restrictive or punitive. Active mediation strategies align with a life-course model of relationships and developmental growth that balances a respect for each individual’s ability for agency and for the communion of the relationship.

The chapter also examined the many factors that can influence the ways parents’ mediate, which can contribute to conflict or to the lack thereof. Key within these is the generational difference in parents’ own knowledge and use of technology. When children grow up knowing more, and “reverse mediation” occurs, the power dynamic can shift. In some homes, this can be sensitive. The dynamic shifts as well when parents’ technology use leads to their being distracted from their children. This sends a strong non-verbal message about the importance of the relationship, and can have damaging effects on parenting, on the relationship, and consequently on child development. As technology continues to evolve, and as generations of children and parents change in their knowledge, skills, comfort, and expectations about using technology individually and with each other, the clear message for both parents and children is one of intentionality.

As technology continues to evolve, and as generations of children and parents change in their knowledge, skills, comfort, and expectations about using technology individually and with each other, the clear message for both parents and children is one of intentionality.Shin et al. (2021) advocate for a life-course perspective in the future design of technology to promote the parent-child relationship:

Technology design that supports relationships must be responsive to the dynamic environment and transactional nature of relationships; accordingly, designers should be aware of technology’s role, and find ways to provide users with timely suggestions. The family life course development approach provides a theoretical lens by which design can incorporate a family’s transactional nature. The theory’s central assumption is that the family’s developmental process is inevitable, and that individuals’ lives change dynamically over time. It further explains how the lives of individual family members, such as parents and children, are interconnected, and how families transmit their assets and disadvantages to the next generation. [p.441:22]

For parents, technology visionary and parent danah boyd suggests approaching technology with an attitude of flexibility (Tippet, 2017):

From my perspective, it’s about stepping back and not assuming that just the technology is transformative, and saying, okay, what are we trying to achieve here? What does balance look like? What does happiness look like? What does success look like? What are these core tenets or values that we’re aiming for, and how do we achieve them holistically across our lives? And certainly, when parents are navigating this, I think one of the difficulties is to recognize that this is what your values are, and they may be different from your child’s values. And so how do you learn to sit and have a conversation of “Here’s what I want for you. What do you want? And how do we balance that?” And that’s that negotiation that’s really hard. And so I think about it in terms of all of us — how do you find your own sense of grounding?

- The volume of research on parenting styles should motivate readers interested in this concept and in parent-child relationships and technology to seek out specific, current, and cross-cultural/cultural literature. ↵