Chapter 5: Technology Use and Impacts in Children, Youth and Young Adults

Passion rebuilds the world for the youth. It makes all things alive and significant.

― Ralph Waldo Emerson

Chapter Insights

- Normative development is both universal in developmental tasks from birth through young adulthood in children, yet unique to the individual.

- Information and communications technology may have a positive or negative influence on physical, socio-emotional, psychological, and cognitive/learning domains of development in each age group.

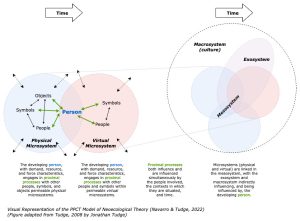

- Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological framework is updated by Navarro and Tudge to address technology’s influence across the micro-, meso-, exo-, and macrosystems and as represented through processes by the person in context over time.

- ICT’s impact can manifest through exposure, interaction, and displacement.

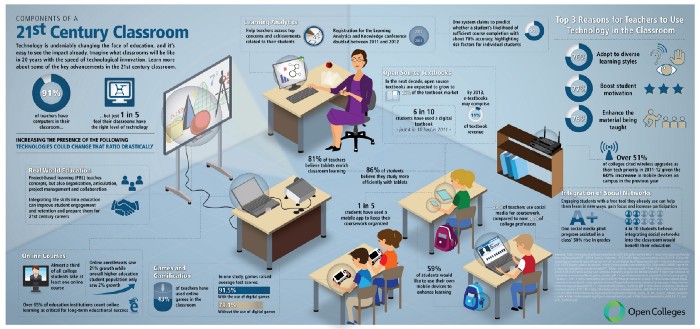

- Technology is increasingly integrated into education and learning, which has a direct bearing on the development of children, particularly during their experiences in school settings. At the same time, there is concern that technology use may have a negative impact on brain development and activity, and on learning.

- Recommendations for children’s safe and effective use of technology are promoted by groups such as the American Academy of Pediatrics. These recommendations vary for young children ages 0–5 and for children and teens. A major study identified ICT impact differences in teens who were “family-engaged” and those who are “high risk.” It too offers recommendations for healthy teen use.

- The age at which most children possess smartphones is younger than the age most parents believe a child is ready. There are factors that parents can look to that indicate a child’s readiness for smartphone use.

- Children’s privacy may be compromised by their use of technology, and may impact their development. Across the ecology of children’s lives, individuals and society are responsible for ensuring that children’s data is safe, their identities are protected, and their accounts and time online are secure.

- After reading this chapter, identify what you feel inspired by, the questions that remain for you, and the steps you can take for your own technology use to be more intentional.

Introduction

Interest in children’s use of technology and its effect on their well-being and development has captured our collective interest perhaps more than any other topic on technology and the family. According to UNICEF (2017), children and adolescents under the age of 18 make up about one-third of internet users worldwide. Yet, as we’ve discussed, use is not a uniform concept, nor is technology a stable phenomenon. As a relatively new phenomenon, interests vary. Populations born in the 1990s and later are growing up with ICT; they know no other life and are digital natives. Older millennials and earlier generations (including the author’s baby boomer generation), in contrast, saw the internet and personal and mobile digital media come into our lives; we are, as Marc Prensky put it, digital immigrants. Technology is a marvel and a mystery we view within an ever-shrinking sense of the “before times,” our lives before the internet. We know how we went to school, met our partners, navigated our way in a new city, and looked up the definition of a word without personal computers and the internet. We see the ease at which younger millennials and genZ-ers adopt (and depend on?) devices, use the internet, succumb to the pleasures and trappings of social media, and are advantaged in their learning by new educational technologies (for those so privileged). And we wonder…

- about children staring at screens and the effect the exposure to blue light has on their brains and sleep.

- about preteens absorbed in social media apps on their phones at all hours of the day, and about the interactions with others who might influence their self-esteem and self-confidence and possibly contribute to depression. Their exposure to graphic images and pornography might be confusing and may be an early influence for later high-risk behavior, and misinformation may frustrate eager learners.

- about teenagers inside on gaming devices for hour after hour, and wonder if it is displacing the joy and understanding of nature. Their social media use exposes them to shared images of celebrities that contribute to self-comparison and body consciousness.

- about young adults using Venmo to instantly send money and ApplePay to cover the cost of coffee and wonder if these efficiencies are displacing learning skills for financial management.

In short, excessive time spent on screens, exposure to specific content, and interactions with those who threaten safety raise concerns about technology’s influence on development, life skills, and achievement, as documented by groups like the American Academy of Pediatrics. excessive time spent on screens, exposure to specific content, and interactions with those who threaten safety raise concerns. Yet to approach children’s use of technology wondering only about its harm is to seek half the story. Yet to approach children’s use of technology wondering only about its harm is to seek half the story. Might these efficiencies and opportunities stimulate creativity and identity expression in ways earlier generations never experienced? Imagine the empowerment of the teens affected by the 2018 mass shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, who used their voices through social media and internet presence to speak out against gun violence. Might the current generation indeed be better off because it has access to a boundless world of information, a universe complementary to a place-based world for interaction and learning, and limitless information sharing? And as with all questions aimed at large groups, for whom might the benefits be greater? Or smaller? And what conditions encourage those effects?

The chapter addresses ICT use and developmental impacts for children from birth through 18, the age defined by the UN Convention of Rights of the Child (UNICEF, nd), and through emerging adulthood (19–25 years).[1] Including young adulthood not only contributes a unique period of development to the discussion (Arnett, 2007), but represents continuity in the parenting experience for many families.

The chapter focuses on the breadth of human development in multiple domains[2], technology use by age, and impacts on the child’s developmental well-being. In most cases, use and impacts derive from research and reports on the specific age group (e.g., middle childhood, adolescence), though they may pull from cross-age data (e.g., the EU Kids Online study includes ages 9–16). Following the ecological focus of this book, the chapter applies this approach to human development, and to implications for families, practitioners who work with children and families, and the wider community, society, and institutions.

As scholars have observed, this digital ecology in which children use and are impacted by technology is not linear; interactions have transactional and dynamic effects. Conceptual frameworks that lay out the ecological, transactional nature of technology’s use and impact on children encourage readers to formulate questions about influences on use and on outcomes that the text may in fact answer. If they don’t, these are likely excellent research questions that individual readers may want to pursue through discussion, a literature search, or a project.

The family-perspective focus of this book encourages us to emphasize the benefits and challenges that reflect parenting interests (Auxier, et al., 2020; Livingstone & Blum-Ross, 2020) and parenting influence (CommonsenseMedia, 2016; Coyne, et al. 2017; Livingstone & Blum-Ross, 2020; Wartella, et al., 2013). This includes the wider ecology of children’s lives and the internet as part of those lives — and of their families — as a critical component of focus. As Sonia Livingstone and co-authors observed (2015)

As the internet has become a routine part of children’s lives, embedded into their lifeworld in a host of increasingly taken-for-granted ways, research is called to examine children’s engagement with the world not only on but more importantly through the internet. Arguably, the question is no longer just that of children’s relationship with the internet as a medium, but also with their relationship with the world as mediated by the internet in particular and changing ways. (p. 9)

An overview of impacts on development

In 2017, the UNICEF report Children in a Digital World summarized technology’s impacts (pp. 4–5):

- Digital technology has already changed the world, and as more and more children go online around the world, it is increasingly changing the experience of childhood.

- Connectivity can be a game changer for some of the world’s most marginalized children, helping them fulfill their potential and break intergenerational cycles of poverty.

- Digital access is becoming the new dividing line, as millions of children who could benefit from digital technology are missing out.

- Digital technology can also make children more susceptible to harm both online and off. Already vulnerable children may be at greater risk of harm, including loss of privacy.

- The potential impact of ICT on children’s mental health and happiness is a matter of growing public concern, and an area ripe for further research and data.

- The private sector — especially the technology and telecommunication industries — has a special responsibility and a unique ability to shape the impact of digital technology on children.

These observations reflect technology’s potential impacts on all domains of child development: physical growth, cognition, learning, and psychological, social, and emotional development. They align with the ages and stages of development: early childhood (birth to age 5), middle childhood (5–12), adolescence (13–18), and emerging adulthood (19–25), which supports a lifecourse perspective (Casimiro & Nico, 2018; Lim, 2016). They reflect differentiated effects depending on the child (e.g., age, gender, susceptibility, personality, health status), the context of use, type of device or application, degree of exposure, and the quality of interaction, and may reveal possible displacement effects (i.e., what the child is not doing while using technology). They commit the technology industry to action that promotes children’s development in design, dissemination, and data gathering. And they reflect the realities of research in the area, which is prolific yet incomplete (Gottschalk, 2019).

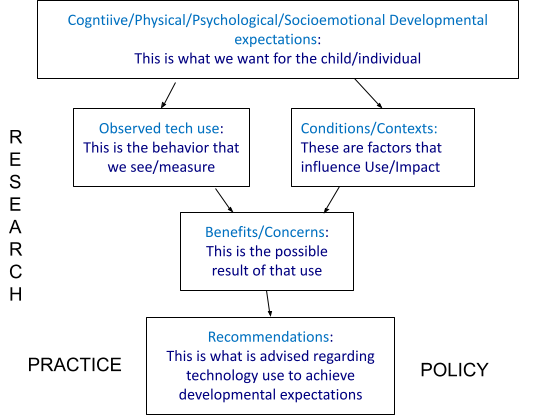

The figure below presents the dominant interest in children’s development as the basis for observation and exploration in research, and for the application of findings in practice and policy.

Perspectives on Human Development

To set the stage for the chapter, and for our understanding of human development in context and the influence of technology at multiple levels, we review Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological perspective of human development with an updated perspective specific to children’s technological realities. This review both contemporizes standing theory and lends itself to identifying frameworks for research, policy, and industry action.

General overview of human development

Individual perspectives on human development refer to the domains of cognition and learning, physical change, socio-emotional growth, and psychological functioning. Each domain operates as a whole, and trajectories of growth in each follow universal dimensions (i.e., those normative aspects expected of all human beings) expressed in unique ways depending on the DNA of the individual and the contexts that facilitate that expression. During puberty, for example, the expression of secondary sexual characteristics such as breasts and body hair due to increasing levels of gonadal steroids is normative in individuals who were assigned to be female at birth (AFAB). Yet the the timing of when breasts and body hair develop, and the expression of breast size and hair thickness, are unique to the genetic material of the individual. So while we regard developmental expectations across ages of children that are somewhat predictable, we also respect that there is variation and great individual difference.

An ecological focus

Studies of individual development through interaction with technology can focus on a physiological level and one quite unique to the developing organism. For example, a researcher might study eye gaze, visual scanning, and face recognition on video images in very young infants (e.g., 6 months, Smith et al., 2021). Or sleep quality and duration might be examined in children related to blue screen exposure and the suppression of melatonin (Hale et al., 2019). Because children do not grow up in a laboratory under constant conditions, research on human development also tries to control for and understand the influence of context (e.g., nurture vs. nature). The child’s context encourages questions about conditions that influence these outcomes. In the case of blue screens and sleep, might the timing or the content of the media (as influenced by actors in the child’s setting) play a role? Individual difference theories propose that sleep disturbances may drive technology use: isn’t it possible that children with poor sleep (due to context influences such as stress) turn to their computers, which exacerbates sleep challenges?

When talking about interpreting quantitative data on the impact of educational technologies and children’s learning, Scott McLeod (2022) stated in a discussion forum of ISTE (International Society for Technology in Education):

One of the challenges of education is that everything is always so contextual. Kids vary, families vary, institutional climate and history vary, our educators vary… everything varies — quite significantly — across schools, culture, geography, time, and context. In other words, what works for one school may not for another, simply because of context or timing (and vice versa). Teasing this out is incredibly challenging but “why did it work (or not)?” is a much more important question than “did it work (or not)?”

With clear respect to the ongoing research on technology’s impact on the biological and physiological processes of the developing organism, our focus on developmental outcomes places focus on contextual influences.

Neo-ecological perspective: “Technologizing Bronfenbrenner”

A critical contribution to the study of human development and the role of technology was offered in 2022 by Navarro and Tudge. By “technologizing Bronfenbrenner,” the authors make two important enhancements to the traditional model that nests systems of interactions as processes that occur over time. As noted in previous chapters, Bronfenbrenner’s model features contexts of interactions, most proximal to the developing individual (microsystem), including the mesosystem (two or more microsystem interactions), exosystem (interactions that influence development yet one of which does not directly contain the individual), and microsystem (wider forces such as culture or public policies) that have an indirect yet potent influence on development. For their first adaptation, Navarro and Tudge identify two parallel and interacting microsystems.

The internet is added as an environment for personal interaction alongside the physical. Their proposed virtual setting is defined as

A virtual microsystem is a pattern of activities, social roles, and interpersonal relations experienced by the developing person on a given digital platform with particular relational and symbolic features that invite, permit, or inhibit, engagement in proximal processes within that environment. (p. 4)

Unique characteristics of the virtual microsystem include synchronous and asynchronous interactions, which affect the individual’s availability and presence; interactions that operate publicly and are persistent due to the ability of platforms to store data that can be retrieved; and interactions that occur with limited interpersonal cues. They observe that the individual can exist in virtual and physical microsystems at the same time, and that interactions in which the individual engages define the opening and closing of virtual microsystems.

Then, after accepting Bronfenbrenner’s definitions of the mesosystem and ecosystem as inclusive of the digital world, they adapt the macrosystem with an integration of Tudge’s (2008) definition of culture:

A group of people who share a set of values, beliefs, and practices; who have access to the same institutions, resources, and technologies; who have a sense of identity of themselves as constituting a group; and who attempt to communicate those values, beliefs, and practices to the following generation. (pp. 3–4)

The adapted macrosystem effects indicate how “the rapid adoption of digital technology likely differentially impacts the development of adolescents depending upon the values and beliefs, resources, and social structure of their society” (Navarro & Tudge, 2022, p. 8). They offer the example of lower-income teens from Ghana using the internet for health information — a finding contrary to most research supporting the behavior in higher-income children — as a response to a more sexually repressive culture. Ghanian teens seek out the internet for information that is not otherwise available to them. Government censorship of the internet, as in China, is another culturally specific influence from the macrosystem. And certainly a key marcrosystem force is the digital divides created by differentials in access to the internet and to devices.

The second contribution from Navarro and Tudge’s technologic adaptation of Bronfenbrenner’s framework focuses on the person-process-context-time construct Bronfenbrenner used to explain how development occurs across influences from proximal and distal systems. In so doing, they integrate examples of personal characteristics that influence systems interactions, and also serve as outcomes, sub-labeled as force, resource, and demand. Time characteristics include micro time, meso time, and macro time, and then proximal processes, or “the conduit for synergistic interrelations between the characteristics of the person and their environments across time” (p. 11). They assert that proximal processes can take three forms: symbolic, relational, and complex, and observe that

development is the result of the multidirectional interrelations, or synergy, between these constituent elements. Person characteristics, context, and time are interdependent; all three forces synergistically shape “the form, power, content, and direction of the proximal process” (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006, p. 798), which in turn influence elements of the person, context, and time. As such, operationalizing neo-ecological theory requires scholars to embrace longitudinal designs and to gather data not only about people and their environments but also about the interactions and activities going on within them. (p. 13).[3]

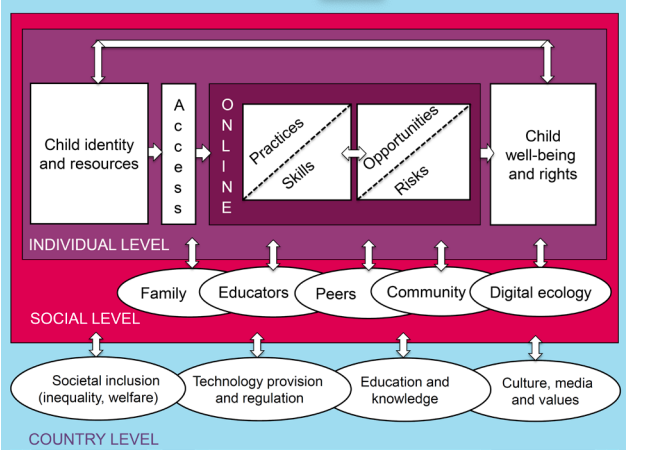

EU Kids Online Framework

The research framework adopted by a set of researchers in the European Union conveys a related notion of contextual influence on children’s technology use as an interaction across multiple settings. The framework model is provided in the figure below.

A primary interest of the EU Kids online study is children’s well-being related to the risks they encounter through online interactions. Risks can be aggressive, sexual, value-related, and commercial, and with each the child can be a receiver, a participant, and an actor. In their framework, children’s online practices, skills, opportunities, and risks can be viewed as virtual microsystem interactions. Those interactions may include one or more in their social setting (e.g, parent, peer), and may be both virtual and physical, which would identify them as mesosystem interactions in Navarro and Tudge’s framework. Interactions by others in the exosystem can influence the child’s online practices and skills — through, for example, actions taken in the child’s community to make computers available at a public library, thus enhancing children’s digital ecology. The country level in the EU Kids framework offers multiple macrosystem actors: technology provision and regulation, culture, media and values, and societal inclusion. With the direction of influence from settings as synergistic, the researchers promote the interdependent nature of the settings, processes, and individuals.

With these ecological, dynamic, and technologically focused frameworks establishing the multi-context influences on children’s development, and with the child’s own behavior as a focus, we explore each age and stage of development and the current knowledge of technology use, influences on use, and impacts on child well-being.

Young Children and Technology

Development overview

The period of development from birth[4] through age 5 is one of the most dynamic of a human’s life. The rate of the body’s physical development body is rapid, and early development of large and fine motor skills occurs, though as with body length and weight, further development occurs at later ages.[5]

Most exciting is the development of the brain. Very early neural connections establish pathways for lifelong learning that affect both brain functioning and brain size. Children’s environment is critical to the development of these neural pathways, as environmental stimuli encourage initial and deeper connections. Children’s neural connections develop paths for future learning during a critical time period of plasticity (Gottschalk, 2019). With brain development, young children gain abilities with executive functioning (sense of organization of information, retrieval, memory), language and literacy, and a sense of self. These are aided by their abilities to move about and use their hands, mouth, and ears to explore and gather information.

Yet comfort with and attachment to their caregiver are key to children’s natural exploration for learning. Through social interaction early in life that conveys a sense of consistency and trust, children develop a connectedness that encourages their confidence. As they explore and have opportunities to interact with others, children gain an interest in being social and move from “parallel” play (playing alongside) to “cooperative” play (playing with others), and to understanding social rules. Through this exploration, the brain continues to develop, and develop stronger neural connections. These early years also prompt an early sense of oneself. A child’s identity begins to form and they roughly understand themselves as unique individuals in the world, and apart from their caregivers. Positive interactions with others in their world reinforce the sense of belonging and self-worth, encouraging exploration and growth.

Overview of developmental achievements in early childhood

- Physical: Rapid brain and body development. Early neural connections establish pathways for lifelong learning. Early development of large and small motor skills.

- Cognitive: Early learning with brain development. Gaining abilities in executive function, memory, language, and literacy. Exploration and curiosity can mean adult perception of misbehavior.

- Social/Emotional: Establish early nurturing connectedness (attachment) with a primary caregiver which offers a sense of confidence and trust for exploration and growth. Early socialization develops through interactions with others, including peers.

- Psychological: Early development of a sense of self, self esteem, and self-concept.

Young children’s technology use

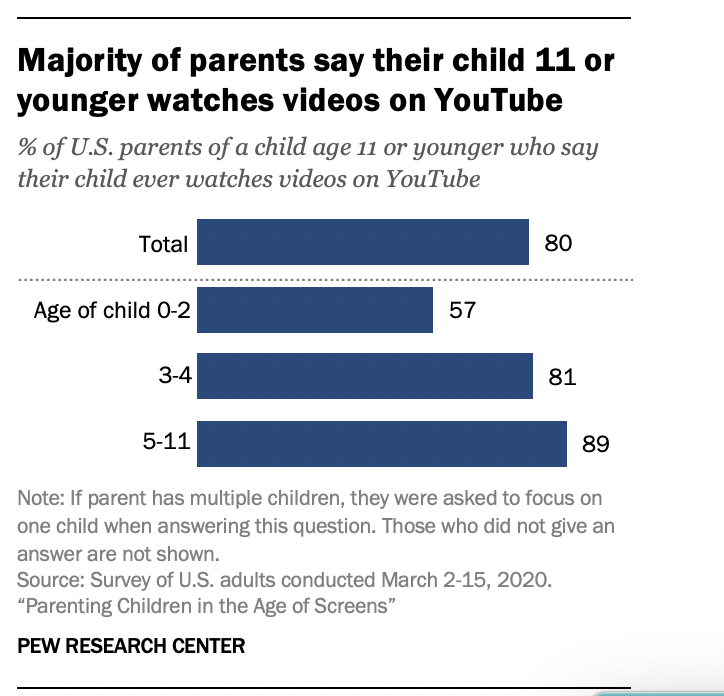

Country government agencies recommend no screen exposure for children under 2 (see table below). Guidelines for very young children center more on limiting exposure rather than recommending use, up to 60 minutes for children 3–4 years, providing that there is adult interaction during use. (Gottschalk, 2019; WHO, 2019). Nevertheless, young children’s time with screens is reported to be just under one hour for children to age 2 (.47), and 2 hours 39 minutes for children 3–5 years, with the majority of time on TV (Commonsense Media, 2017). Young children’s exposure to digital technologies may begin months after birth (WHO, 2019). Auxier et al. (2020) report that nearly half (48%) of children under 5 have used a tablet and 55% have used a smartphone. Of parents who stated that their child 12 years or younger has used a smartphone, 6 in 10 reported the child began engagement with a smartphone before the age of 5, and roughly 1 in 3 reporting their child began before age 2 (Auxier et al., 2020). YouTube is popular with very young children, with up to 80% having watched it, and 25% watching it several times a day. Black and Hispanic parents reported higher rates of YouTube viewing several times a day. These parents are also more likely to report concerns that their young children are exposed to potentially negative images and messages, such as sex, violence and drug use, and gender and racial stereotypes. (Commonsense Media 2017). U.S. parents also report that approximately 5% of children under 5 use social media (especially TikTok and Snapchat), and 29% say their young child interacts with a voice assistant (e.g. Alexa, Siri), primarily to play music (reported by 79%). Throughout this chapter and in later chapters (e.g., cCapter 7 on parent-child relationships and technology), we explore parent and family contexts that influence young children’s technology consumption.

Technology use in early childhood education and child care settings

While much of the research on young children’s technology use is gathered from parents, many children attend child care and/or early childhood education and are exposed to digital devices and the internet by teachers directly or indirectly (e.g., from teachers’ personal use around children). many children attend child care and/or early childhood education and are exposed to digital devices and the internet by teachers directly or indirectly (e.g., from teachers’ personal use around children). According to the National Center for Educational Statistics, in 2019 parents reported that 59% of children 5 years or younger and not enrolled in kindergarten were in some type of nonparental care. Of these, the majority (62%, or 37% of the total) were attending a day are center, preschool, or prekindergarten (center-based care). Smaller numbers were cared for by a relative (38% of those in care) or in a private home by someone not related to them (20%).

A recent review of the literature by Undheim (2022) categorized technology in early childhood center settings as screen-based, not screen-based (e.g., 3D printers), Internet of Toys (IoT), and exploratory technology (e.g., digital telescopes). The studies focused on either the children’s perspective or the teachers’, and were primarily concerned with the pedagogical value or use of the technologies. They also observed discussion of access differentials between home and school, and teachers’ knowledge, skills, and beliefs. Both areas are considered disconnects in children’s valuable use of digital technology (e.g., teachers who have open attitudes and skills are more likely to provide meaningful interactions and sustained learning). The author observes that the majority of the studies lean toward a more positive view of children’s learning and play with technology, and rarely lend a critical eye to use. Some of the effects of children’s technology use in early childhood settings identified from research are discussed in the next section. [6]Discussion of teacher competence and skill with technology is discussed in Chapter 11.

Interests in young children’s development related to technology

Brain development and its related functions of language and problem solving, exposure to content that may be challenging for children to understand, the quality of sleep ,and body weight are all key interests in research on technology use by children from birth to age 5. For preschool-age children (2 ½ to 5 years), there is some demonstrated benefit of well-constructed media in acquiring alphabet recognition and learning sounds, and in greater emotion recognition, empathy, and self-efficacy. Young children are creators with technology, producing stories with rich narratives, characters, and representations of their social understanding (Undheim, 2022). A key to these benefits is the interaction and presence of an adult.

Research also indicates that excessive TV watching reduces language, cognition, and socioemotional development, largely due to reduced parent-child interaction. There is concern that early behavior with TV watching will establish a habit in children. The quality and content of TV is another consideration, particularly when children are exposed to content that is not prosocial. Children who form a habit of passive TV or screen viewing also are at risk of early obesity. Not only is passive viewing a sedentary activity, but it exposes children to commercial content that promotes lack of exercise and high-calorie eating. And sleep issues have been observed in young children who have media in their rooms. Diminished sleep is observed when infants are exposed to blue light from screens, which suppresses endogenous melatonin. The content of what is viewed can also create an elevated heart rate, making it hard for young children to sleep. A focus on screens can negatively affect babies’ need for reciprocal interaction for learning language, a sense of self, and executive functioning (Ernest et al., 2014; Gottschalk, 2019).

Recommendations to date

The table below lists guidelines for young children (and older groups) as stated by professional agencies in the U.S., Canada, and selected countries. No screen time is recommended for infants and toddlers (under the age of 18 months), except for occasional video chat (per the AAP). As noted, any programming should be intentionally selected for quality, and interactivity with an adult is key. If we consider the multiple advantages of a caregiver reading a book with a child, the value of using technology with a young child is evident. When reading with a caregiver, children better understand language and the context of language and literacy, they can be scaffolded to apply content from existing text and their questions can be answered, and the emotional connection when reading and responding with another reinforces neural pathways. With screens, having a peer or parent is especially important to help cognition. Research indicates that it’s not the medium (video screens) that is a barrier to learning, but the lack of a partner to help children make sense of what they are seeing and interacting with (Lytle et al., 2018).

Screen time recommendations (from Gottshalk, 2019)

| Country/institution | Infants/toddlers | Early childhood | School-age – adolescence | Other recommendations | |

| AAP (United States) (AAP, 2020) | None, except video chatting (under 18 months) | 1 hour of high quality programming, co-view | Consistent limits on time and type | Turn off screens when not in use; ensure screen time doesn’t displace other behaviors essential for health | |

| Canada | None | <1 hour | <2 hours (CSEP only) | Limited sitting for extended periods (CSEP); adults model healthy screen use (CPS) | |

| Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP, 2017) | |||||

| Canadian Paediatric Society (Canadian Paediatric Society, 2017) | |||||

| Australian Government Department of Health (Australian Government Department of Health, 2017) | None (under 12 months); | <1 hour | <2 hours (entertainment) | ||

| New Zealand Ministry of Health (Ministry of Health, 2017) | None | <1 hour | <2 hours (recreational) | Adapted from CSEP guidelines | |

|

German Federal Ministry of Health (Rütten and Pfeifer, 2016) |

None | 30 minutes | 1 hour (primary school) – 2 hours (adolescents) | Avoid as much as possible; avoid screen time completely for children under 2, including background television |

A shorthand version of recommendations for young children by the American Academy of Pediatrics states:

- No screens under age 2.

- Limit to 1 hour a day (2–5 yrs).

- Use technology along with children.

- Limit their exposure.

- Observe what it’s displacing.

- Limit when they use (not close to bedtime).

- Limit where they use.

Experts agree that children must be prepared for technology use in their future (Ernest et al., 2014). To do so, we must view the internet and mobile, digital devices and applications realistically in terms of both their benefits and ways they can be detrimental. This requires ongoing synergy between research, practice, and policy, so that information and action from one sphere inform the others. The report also observed that caregivers and educators can help children recognize how their identities, knowledge, skills, and values are shaped by forces around them (social, cultural, and political), by how they are represented in the media, and by their online interactions.

The Erikson Center for Technology and Early Childhood offers guidelines for media literacy in young children. These may serve as goals or indicators of success:

Erikson Center Media Literacy Guidelines for Young Children[7]

- Children will learn to intentionally access, select, and manipulate media.

- Children will learn to engage and explore with media in a way that is supportive of their overall development and learning.

- Children will learn to comprehend media messages and practices.

- Children will learn to critically inquire about media and their use of media.

- Children will learn to evaluate the content and impact of media in a developmentally appropriate way.

- Children will learn to create and express ideas using media.

To encourage these skills in children’s worlds, Erikson CML also provides recommendations for caregivers and practitioners. These are general reflections on understanding oneself as a learner and teacher, and underscore the AAP’s recommendations. Additional information for both of these groups is provided in Chapters 6 and 7 (for parents) and 11 (for practitioners).

With regard to research priorities, the EU Kids online framework (2015) includes the following areas:

- Factors relating to children’s identity and resources, beyond demographic variables.

- New modes of access to the internet, as this becomes more mobile, personalized, and pervasive.

- A multidimensional analysis of digital skills and literacies and their significance for well-being.

- A rethinking of the “ladder of opportunities” to identify whether and when children undertake more ambitious creative or civic online activities.

- New kinds of online risks, including risks to personal data, privacy issues, and online reputation management.

- The interplay between children’s digital practices and proprietary policies and mechanisms.

- Children’s desire to experiment and transgress boundaries, to grasp children’s agency online.

- Extending the analysis of how parents mediate their children’s internet use to the potential importance of other socializing agents.

- Extending research on use of digital media from 9-to 16-year-olds to much younger children.

- Research on socio-technological innovations in smart/wearable/ubiquitous everyday devices.

- The implications of digital engagement as it may reconfigure (undermine or enhance, alter or diversify) children’s well-being in the long term.

- Connecting the research agenda on children’s online access, risks, and opportunities to the broader agenda of children’s rights — provision, participation, and protection — in the digital age.

Middle Childhood and Technology

Development overview

Middle childhood[8], ages 6–12, has been called a “latency” period of human development. Compared with the dynamic rate of growth in the early years, and the rapid changes that occur during early, middle, and late adolescence, skeletal and muscular growth and dexterity happen at a slower rate. Cognitively, learning moves to the operational stage, with abilities to organize and use logic to solve problems. Many children at this age enjoy playing games with rules, collecting, and developing a type of expertise. They are also often eager to explore and learn new things. Socially, exposure to peers is significant during middle childhood, as the majority of children begin formal schooling. They also have opportunities for afterschool programs, clubs, sports, and other activities with peers. As children are learning to cooperate with others, they may be subject to bullying and other expressions of power. Psychologically, children in middle childhood are continuing to develop an identity of themselves, as a part of the family, yet also as unique individuals.

Overview of developmental achievements in middle childhood

- Physical development: Slower body rate of growth; fine and large motor skills continue to be refined. Puberty at the end of this stage.

- Cognitive/brain/learning: Thinking becomes more logical and ordered; able to use if-then perspective; expertise, moral development, and ethical behavior.

- Social/emotional development: Peer socialization; exposure to bullying from the assertion of power in peer groups.

- Psychological: Strengthening a sense of gender identity, self as separate from family.

Technology use

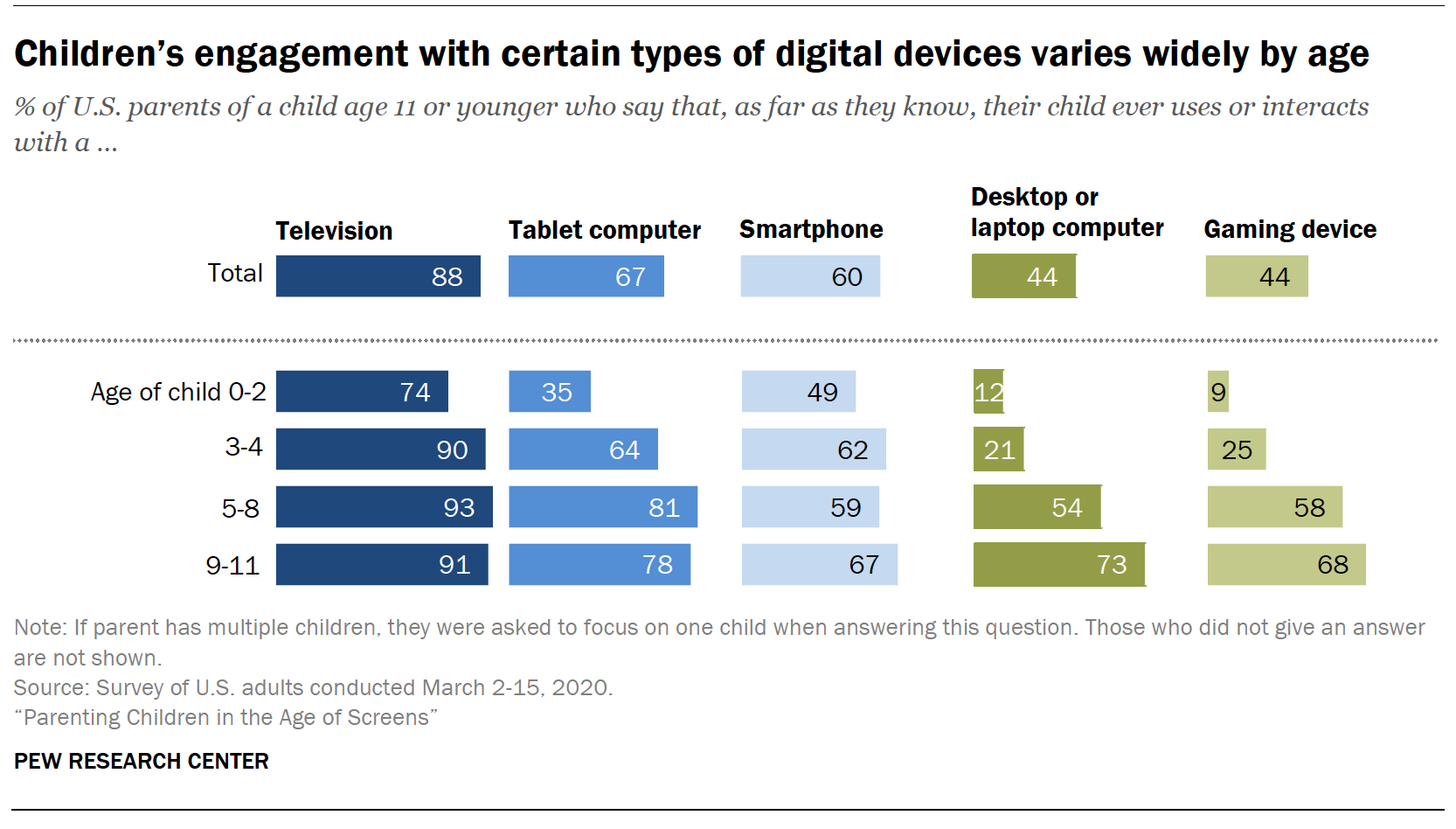

Interest in activities, stronger peer relationships and time spent in school/on school subjects encourage children 6-12 years old to use a variety of devices and explore a range of applications. School-age children are prevalent media users, with 80% using a tablet and 63% using a smartphone (Auxier et al., 2020). Even so, only 22% of parents feel it’s OK for children under 12 to own a smartphone. They are more tolerant of children having a tablet, with 65% reporting that a tablet is acceptable for children under 12. As indicated in the chart below, over half of school-age children age 5–8 and 9–11 have used all five types of devices listed. Larger use differences between school-age and younger children exist for computers and gaming devices.

A 2021 report from Commonsense Media indicates that average screen time use by tweens (ages 8–12) increased 17% from 2015 to 2021, from 4 ½ hours to 5 hours 33 minutes. As observed with teens (and discussed later in the chapter) screen time is greater among boys, children who are Latino, and those in families with less income. YouTube is popular with children, with 89% of parents reporting that their 5–11-year-old watches videos on YouTube (Pew). Just over half (53%) report that their child watches YouTube at least once a day. Commonsense Media reports that “tweens watch an hour of online videos per day.”

Social media is popular with children ages 9–11, with parents reporting 30% on TikTok, 22% on Snapchat, and 11% on Instagram. Commonsense Media (2021) reports that 11% of 8–12-year-olds are on Snapchat and 10% on Instagram (their data was drawn from children, not adults). That said, small portions of children 5–8 years (i.e., 3–11%) are also reported to visit these sites, despite age warnings on the applications (Schaeffer, 2021). Parental acceptance of screens also changes during this age: 67% are tolerant of children under 12 having a tablet, though the majority of parents (73%) believe that 12 or older is the age at which it is acceptable for children to have their own phone (Auxier et al., 2020). And with regard to voice-activated devices, just over one-third (36%) of parents with a child 11 or younger reported that their child had engaged with a voice-activated assistant such as Siri or Alexa. Functions of these devices for children include playing music (82%), providing information (66%), and hearing a joke or playing games (47%).

Impacts

Technology offers a number of potential benefits for children ages 6–12:

- Exposure to new ideas, increased awareness of events and issues, information that reinforces interests.

- Access to information about health and body changes as puberty approaches.

- Enhanced communication with family and friends, especially those geographically separated; enhanced access to support networks through social media.

- Aiding in learning in school and beyond: tablets, media devices for content creation, digital stories, blogs, etc. (digital ecology).

- The expression of identity through interest exploration, creative pursuits, and expression.

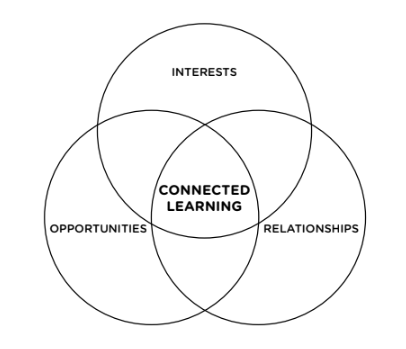

For children gaining enhanced access to technology during middle childhood, “connected learning” promotes the value of interactive, mobile, creative technologies and children’s learning (Ito et al., 2020) and encourages the pursuit of interests across the “learning ecology” (Barron, 2006) through opportunities and relationships.In contrast to learning that takes place in a formal classroom, connected learning builds on learner interests through relationships (with those who will promote deeper understanding) and opportunities (to explore additional ways of understanding and deeper content).

As observed by the Connected Learning Research Network (Ito et al., 2020), connected learning takes root when:

- organizations sponsor and legitimize the interests and identities of diverse youth,

- learners are engaged in shared practices such as creative production, research, or friendly competition,

- these practices are guided by shared purpose such as contributions to communities, social change, or solving real problems, and

- learning is connected across settings through brokering, coordination, and openly networked platforms (p. 5).

In Chapter 8 we discuss a family podcast in which a father and his two children talk about Star Wars. [9] Because of the relationships and opportunities afforded through both children’s interests that integrate technology (one in music, the other in video production), the family’s experiences enable the children to “connect” their learning across multiple spheres — including application in traditional schooling. Readers interested in learning more about connected learning may want to visit the Connected Learning Alliance. The boom in learning technologies used in the classroom — and teacher competencies to ensure pedagogical value — speak to the promise of digital engagement throughout the school years. Technologies used for learning in elementary and secondary schools are discussed later in this section.

Online and videogames are very popular with children in middle childhood. Jessica Navarro, the technology and human development researcher mentioned previously, writes of her son’s experience with playing the online game Fortnite (2021). She admits feeling leery about his play when the hype pointed to the exposure to first-person shooter activity and violence. Yet observing him play with friends, including new friends met online, showed her the value of the game for developing collaboration skills (social) and problem-solving (cognitive), checking two of the developmental domain boxes. An interest in games with rules, and the development of eye-hand coordination during this age, can make participation in online interactive games a positive experience. And very recent research by the National Institutes for Drug Abuse (NIDA) identified a relationship between playing videogames for 3 hours by 9 and 10 year olds and benefits to cognitive tasks involving impulse control and working memory (NIDA, 2022). That said, and as Navarro observes, the online chat features of these games can also expose vulnerable children to bullying and contact with adults (McInroy & Mishna, 2017) and to violence, which can influence the acceptance of oppression and lack of empathy (Ernest et al., 2014). Parental controls can help moderate what children are exposed to, and by monitoring children’s play and, especially, their response to the play, parents can be aware of the value or possible consequences these games afford.

Impacts — Exposure to screens

A primary developmental concern at this age is an over-reliance on screens that leaves children exposed to threats they may not have the cognitive abilities to reason through or social maturity to handle (Gottschalk, 2019). Long hours on computers also contribute to physical health concerns about childhood obesity, blue screen exposure and sleep deprivation, and weak posture. DeMoor et al. (2008) lists three primary areas of concern in internet exposure as content, contact, and commercial. Passive viewing and exposure to influencers on social media (contact) are linked with childhood depression, stress, and anxiety. Concerns have been lodged about children’s lack of privacy and the potential for commercial applications and, as discussed in the next section, even school software to track children’s use, user patterns, and user preferences.

With regard to content, a 2021 report from Commonsense Media looked at representation in the media that children consume, important given that the majority (70%) of parents surveyed wanted their children to be exposed to more diverse images (with higher percentages among parents of color). Parents also wanted media content to expand and be inclusive of other kinds of diversity (individuals with physical, neurological, or learning disabilities, those with diverse body types, and those from different socioeconomic levels). Parents’ media concerns stemmed from the way they felt people were represented in programming to their children. Many parents perceived White people as more likely to be portrayed in a positive light compared to the portrayal of Black, Hispanic/Latino, and LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Learning and Technology

Schools have long integrated multimedia and interactive media to encourage collaboration, creativity, and exploration, and to connect with students at a distance. Greater attention to educational technology has occurred in the last 30 years as computers and the internet, then laptops, then Chromebooks, and now tablets, SMART boards, and smartphones are used in the classroom, and as teaching through virtual environments complements and sometimes replaces face-to-face instruction. Reviews of the research indicate that, when used appropriately, instructional technology can enhance feedback and communication with students, and motivate peer collaboration, individual creativity, and self-expression (Hamilton & Hattie, 2021). UNICEF’s 2022 What Makes Me? report identifies learning technology as a successful modality for children’s active and multisensory work that promotes core capacities. Students are likely to continue interactions outside of school, and parents can feel more engaged and involved.

“From the plethora of media comparison research conducted over the past 60 years, we have learned that it’s…the instructional methods that cause learning. When instructional methods remain essentially the same, so does the learning, no matter which medium is used to deliver instruction” (Clark & Meyer, 2011, p. 14; as cited in McKnight et al., 2016, p. 195).

Research also indicates that devices and applications are merely tools; the quality of the teaching with these applications is key to effective learning. Research reviews about instructional technology and learning report that the motivation to learn is key. Instructors are critical to this motivation — in the ways in which they adapt technology through learner-centered approaches, emphasize how people learn, differentiate and individualize instruction, and use technology to facilitate learning processes (p .195, McKnight et al., 2016). In addition, teachers who use instructional technology find their work to be more efficient — particularly in student communication and grading homework — giving them more time to focus on instruction. How well teachers implement instructional technology is greatly dependent on their ability, training, and resources (discussed further in Chapter 11, and in Hamilton & Hattie, 2021).

The wider infrastructure of schools can create a culture that integrates technology as a pedagogical tool and embraces teaching strategies with technology. Associations like ISTE (International Society of Technology in Education, iste.org) offer tremendous resources, learning opportunities, and community forums for teachers to identify materials and strategies for effective instruction. Standards for teaching training and licensing and for school integration provide guidance for the entire field of formal pre-K-12 education in the U.S. and globally.

Possible pitfalls of educational technology

As with most issues, however, learning technologies in education are not always the ideal solution. A significant challenge is that of access. Individual households, schools, and school districts vary by geography and income in their ability to ensure children’s access to devices and the internet (Hamilton & Hattie, 2021). The ability of parents and educators to support children’s learning with new technology also varies greatly. An example of this is the software Prodigy™, with English and math games for children. While it provides a fun and immersive experience, families and schools may be unable to upgrade children’s free accounts to a premium (cost) version, marketed to users. Using a premium version entitles children to exclusive rewards, leaving those unable to upgrade to feel like they are missing out. Groups like Commonsense Media recommend that schools jointly create community strategies with families to make decisions that benefit children while being balanced with cost considerations.

Privacy and data sharing are other issues with learning technologies used by schools (Lieberman, 2020). When selecting software for children’s learning, schools vet quality, cost, usability, and security. They are obligated to let parents know how student data is being used, regardless of where teaching occurs. Laws such as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA) and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act (COPPA) offer guidance when selecting software. Yet the rush to putting lessons online during COVID-19 and as schools provide more distance learning options on tight budgets can mean using free programs that are less transparent in their practices. In 2020, Education Week reported that “Most U.S. states earned a ‘C’ or lower grade from a 2019 survey of student data privacy protections by Kiesecker’s organization and the Network for Public Education.” As discussed in Chapter 12, school districts take children’s privacy and data use from education software seriously and offer policies on their websites, in school community handbooks, and in teacher training. It is essential that education technology companies be consistent and clear in their policies, and adhere with legal tenets of privacy laws.

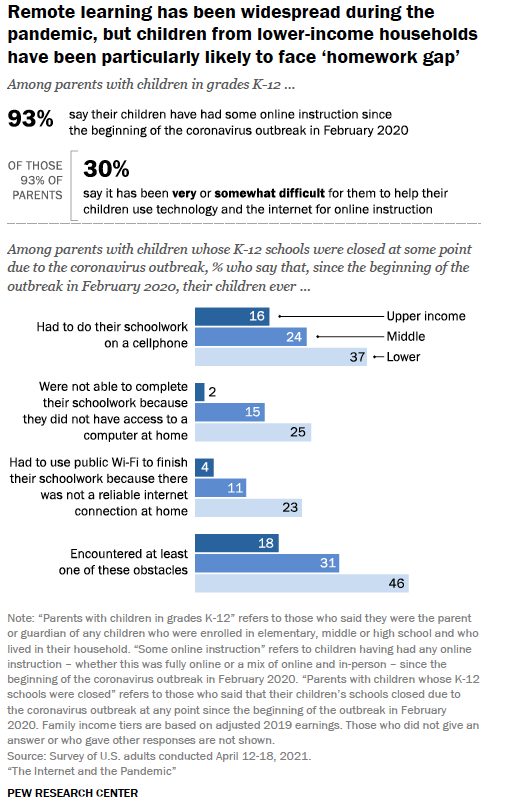

Access to learning technologies

Issues of children’s access and the digital (or knowledge) gap are of worldwide concern. Inequities in device and internet access challenge children’s learning and achievement (Katz, 2017; Katz et al., 2018; Perez, 2021; Resta, 2020; Resta et al., 2018; Zhang & Livingstone, 2019). Differences in access affect children’s participation in learning and at school, the creation of valuable social connections, and the forging of a unique identity. Lack of access also adds a disadvantage to children with special needs, who already struggle to find technologies with necessary accommodations. Schools may distribute devices, routers, and wifi hubs, provide additional technology coaching, and train teachers to be sensitive to equity and access needs when integrating technology in coursework (Perez, 2021). And a new bill (Emergency Broadband Benefit) from the U.S. Congress offers short-term assistance to pay for internet access for families and students (US FCC, 2021). On the public awareness side, children’s media scholars Livingstone and Blum-Ross (2020) advocate that a step toward equity is to move our collective concern away from screen time quantity and more strongly embrace quality dimensions of technology use for active learning, socialization, and development. This can shift attention to the need for all children to have access to beneficial technology.

Children with Special Needs

Technologies can aid reading for children with vision challenges, and vocabulary and problem-solving skills for children with developmental delays (Livingstone & Blum-Ross, 2020). Adding Wii games for children on the Autism spectrum benefits physical development, learning social cues, and developing social skills (Ernest et al., 2014). Commonsense Media reports that videogames can be tailored to specific needs, and games produced for general populations can aid children in acquiring communication skills, providing them ways to challenge themselves and learn how to ask for help.

Beyens et al. (2018) summarized a review of four decades of research on technology’s impact on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) to indicate only a marginal relationship, calling it more “theoretically than empirically grounded” (p. 9878). They called for continued research into individual differences that affect susceptibility (e.g., sex, temperament, age) and especially into context and condition variables that may play a role in technology selection, content exposure, and use, including parent variables. “Research has shown that parents factors, such as parental ADHD, parental temperament, parenting stress, family conflict, unresponsive parenting, and chaotic parenting are negatively linked to ADHD behaviors, and responsive parenting can suppress ADHD-related behaviors” (p. 9879).

Recommendations for middle childhood and adolescence

The American Academy of Pediatrics offers these recommendations for parents of children and adolescents (which includes children in middle childhood):

- Monitor access to devices and use, on balance with physically healthy practices for brain and body.

- Treat media as other environments: set limits, monitor for safety and well-being.

- Be a good role model.

- Promote the value of face-to-face communication.

- Provide warnings for safety (privacy, predators); keep lines of communication open if children/teens experience concerns.

- Focus on appropriateness and quality of engagement.

- Make and communicate media plans with all family members.

- Understand limits and potential harms. Do your homework on apps and games children and teens use.

During this age period, many children will seek and/or acquire a smartphone. Is there an appropriate age for children to have a smartphone? Or is a determination based on knowing the risks and rewards and on a child’s display of the ability to responsibly handle one? Children’s smartphone ownership is discussed later in the chapter. And parent engagement through consistent and attuned communication with children in middle childhood and late, is key to their healthy use. As noted, children ages 6–12 will be exposed to messages and images and information that they don’t understand. It is essential that they have at least one adult they feel safe to go to for questions and conversation about technology.

Adolescents and Technology

Development overview

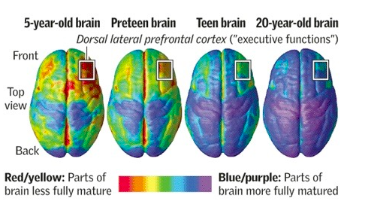

The developmental changes that occur during adolescence are so dynamic and pronounced that development scholars divide the period into approximate age ranges: early adolescence (11–14), middle adolescence (14–17), and late adolescence (17–20).[10] The significant activity of puberty can affect the expression of primary and secondary sex characteristics, hormonal expression leading to an interest in having sex, body changes, skeletal growth, and continuation of brain development (though it’s not complete until later into early adulthood; see figure below).

Adolescents’ contexts are, primarily, in middle and secondary school, exercising their cognitive abilities and continuing peer associations. Expression of identity is key and can encourage the joining of “cliques” and crowds as a way to fit in and understand oneself. The growing sense of confidence in oneself can also unleash under-confidence, expressed as power through bullying others.

Overview of developmental achievements in adolescence

- Physical: Brain development continues (still not complete), body changes in puberty affects hormonal reactions, and interest in sex; opportunities for high-risk behaviors; skeletal and muscle growth is completed.

- Cognitive: Thinking becomes more reasoned and abstract; hormonal response can generate high-risk behavior.

- Socio-emotional: Peer associations, romantic associations; looking ahead; taking on added responsibility in jobs;, anticipating life post-secondary school (military, college, employment, etc).

- Psychological: Identity development (as separate from family); hormonal responses affecting mood; awareness of mental health challenges.

Technology use

Phones and computers are nearly ubiquitous in the lives of teens, who use them extensively for connections to friends and family, for schoolwork and jobs, and for daily life tasks. Most (95%) have smartphones, and 80% have a gaming console. A 2022 report from Pew indicates that these percentages have increased since 2015 (Vogels et al., 2022). Most teens (95%) have smartphones, and 80% have a gaming console. While the majority of teens in the U.S. report having a computer (90%), those whose parents have less education or income are more likely not to have a computer (Anderson et al., 2022)…Among 13–18-year-olds, the average total screen time is 8 hours and 39 minutes. This is an increase of 1 hour per day between 2019 and 2021. As noted in Chapter 3, these socioeconomic disparities in technology access had negative implications for children and teens’ academic participation during COVID. And use varies by gender and ethnicity. Commonsense Media reports that boys spend more time than girls online, as do teens who report non-white ethnicities. Among 13–18-year-olds, the average total screen time is 8 hours and 39 minutes. Light users are on screens for approximately 2.5 hours/day; heavy users for 13.3 hours/day (Commonsense Media, 2021). And use has increased in recent years. In 2019, teen screen time averaged 7 hours 22 minutes. Commonsense Media reports that the rate of increase is greater in the last two years than in previous years.

Teens use a range of social media, with a preference for YouTube, TikTok, Instagram, and Snapchat (Vogels et al., 2022). In just seven years, teen interest in Facebook dropped from 71% to 32% according to the 2022 study from Pew. Boys report more interest in Reddit, Twitch, and YouTube; girls prefer Instagram, Snapchat, and TikTok. While 62% reporting using social media daily, daily entertainment is also sought through streaming videos (77%) and watching television (49%) (Commonsense Media, 2021). Yet even though teens report spending nearly an hour and a half each day on social media, a minority indicate that they like doing so “a lot” (34%). Listening to podcasts as a regular activity is reported by about one-fifth of teens. And gaming is popular with 59% of teens, with active players spending three hours a day on average, and teens in general reporting 1 hour, 46 minutes. The Pew study reports that a majority of teens say their social media use is about right (55%); 36% say it’s too much.

Global data on teen technology use is available from the EU Kids Online study and the Global Kids Online study, which track children’s use in Europe, South America, countries in Africa, and the Philippines. The EU Kids study follows 9- to 16-year-olds (approximately the middle of the two age groups surveyed by Commonsense Media), and the 2016 report from the Global Kids study featured data from 9–17-year-old children from the Philippines, Serbia, and South Africa, and internet-using children age 13–17 from Argentina. These data offer a more universal understanding of technology use by children and teens, with differences to what is observed in the U.S. based on socioeconomic, cultural, and governmental factors.

For example, in a study of Nigerian teens age 13–18 years old in rural and urban areas, most reported access to a shared or personal mobile phone, which was the dominant form of internet access (Uzuegbunam, 2019). A minority purchased their own phones (23%); the remainder reported purchases by their families. However, the researcher determined that use was fairly gendered. Technology for personal development and for self-learning was mainly by privileged male youth in urban cities. The teens also reported the use of social media as positive yet, as with other teens, indicated technology’s power to distract, expose them to bad messages, and encourage cheating on tests. While some parents do monitor teens’ technology use, the research indicated that many parents and teachers lack the skills and literacy to support children’s evolving digital practices.

Texting and using social media for peer communication and for connections with romantic partners are significant for teens. Sexting, or sharing sexual images and language, is fairly common. Madigan et al.’s (2019) research review representing data from the 22 studies in the U.S., Canada, Europe, Australia, South Korea, and South Africa indicated that 8.4% forward a sext without consent, 12% receive a sext without consent, 15% send a sext, and 27% receive a sext. Flirting this way via smartphone (the device used in most cases of sexting) is obviously not common, yet its occurrence is usually consensual. However, sexting laws prohibit sharing personal images of individuals who are minors. Fines and laws can be harsh for those who send sexually explicit or nude photos electronically, whether though text, email, or social media. Some states have specific laws regarding sexting between minors, which are less harsh than those — like Minnesota — whose laws around sexting and minors are related to child pornography. This page provides more information about the statute in Minnesota laws. Writing for Pediatrics (from the American Academy of Pediatrics), Strasberger et al. (2019) cite the data and implications of sexting in teens, and argue for the differentiation of behavior between consenting adolescents and behavior that is clearly in the realm of child pornography and abuse.

Impacts

Despite legitimate concerns on behavioral trends observed with teens and technology, as ICT has become ubiquitous in their lives, the majority of teens do not report negative outcomes (Commonsense Media, 2021). [11] Interaction through dating apps, texting, and social media are commonplace and now expected environments for intimate relationships — a healthy part of teens’ socialization. James et al. (2017) report that, for 13–17 year olds with a social network profile, the applications used intersect interests across their lives, and contribute significantly to adolescents’ identity formation, sense of agency and autonomy, and academic achievement. For adolescents and young adults worldwide, proficiency with technology also means preparation for jobs of the future that will rely on automation (Anderson et al., 2022; Blum-Ross. et al., 2018).

Teens’ use of social media is a good example of research findings that are “variable” in being positive, yet qualified. James et al.’s 2017 review of the research identified positive impacts on well-being through self-confidence, self-esteem, being outgoing, feeling less shy, and reporting less depression. This is often due to social media’s ability to help teens maintain friendships and meet new potential friends with shared interests. With regard to empathy and narcissism, in general teens display more emotionally empathic communication online than adults, yet they are also more likely to think of their activities online from a self-focused perspective. And during COVID-19, teens who found support online, despite the number of hours they used screens, reported positive mental health, based on a study of 700 11–17 year olds in Peru (Magiss-Weinberg et al., 2021).

As with children in middle childhood, concerns for teens’s technology use rest with psychological effects due to social comparison, anxiety, low self-esteem, and being the subject of bullying (UNICEF, 2017). These effects also are more prevalent for teens who are vulnerable. concerns for teens’s technology use rest with psychological effects due to social comparison, anxiety, low self-esteem, and being the subject of bullying (UNICEF, 2017). These effects also are more prevalent for teens who are vulnerable. Variability occurs depending on the content of what is being shared, the quality and quantity of content, and responses from others. For example, when a social media user seeking support is ignored, the user afeels worse. Research by Commonsense Media (2018) revealed that adolescents age 13–17 who scored lowest on the socioemotional wellbeing scale (SEWs) reported the importance of social media in their lives higher than did other teens; they were also more likely to report being bullied or feeling bad and left out. Recently, a young teen’s suicide was attributed by a London coroner to her consumption of self-harm-related social media. Problematic behavior with technology (e.g., feeling addicted to one’s phone) can have negative consequences with relationships. And devices such as mobile phones, with the ability to text and access social media at will, can inhibit intimacy and present challenges through the perception of 24/7 connectedness.

Analyses of literature on videogame violence supports a relationship with players’ longitudinal demonstration of violent behavior, even after controlling for previous demonstration of aggression (Prescott et al., 2018). And researchers found a racial component: a strong relationship for White children, a weak relationship for Asian children, and an unpredictable relationship for Latino children. They echo other scholars calling for continued research on factors or individual differences that relate to the results.

researchers encourage widening the scope rather than narrowly targeting technology as the sole culprit in investigations of effectsAdditional researchers encourage widening the scope rather than narrowly targeting technology as the sole culprit in investigations of effects. Adolescents face a range of influences on their health and mental health. Writing for Nature, researcher Candice Odgers (2018) reports how teens are faring in the “digital age” by offering a broader view than data linked specifically to phone use. She reports on broad indicators like high school graduation rates and academic achievement, and on downward trends in pregnancy, violence, alcohol abuse, and smoking. As noted in Chapter 1, it’s crucial to consider how technology fits into children’s and families’ lives as a whole. Odgers addresses the debate around benefits and consequences of technology use by teens, and returns to a biological truth: developing organisms will respond in unique ways to their environments, and measured impacts in one ecological domain are likely influenced by influences from another. Indeed, and as noted above, some teens will demonstrate negative impacts from exposure to social media, videogames, time online, and use of their smartphones. Yet Odgers’ read of the data is that this reflects “a new kind of digital divide, in which differences in online experiences are amplifying risks among already-vulnerable adolescents.” Her recommendations are that we fret less about technology use and teens as the issue, and focus more on the wider societal influences on their lives that encourage the mental health and academic and behavioral conditions they bring to their online experiences.

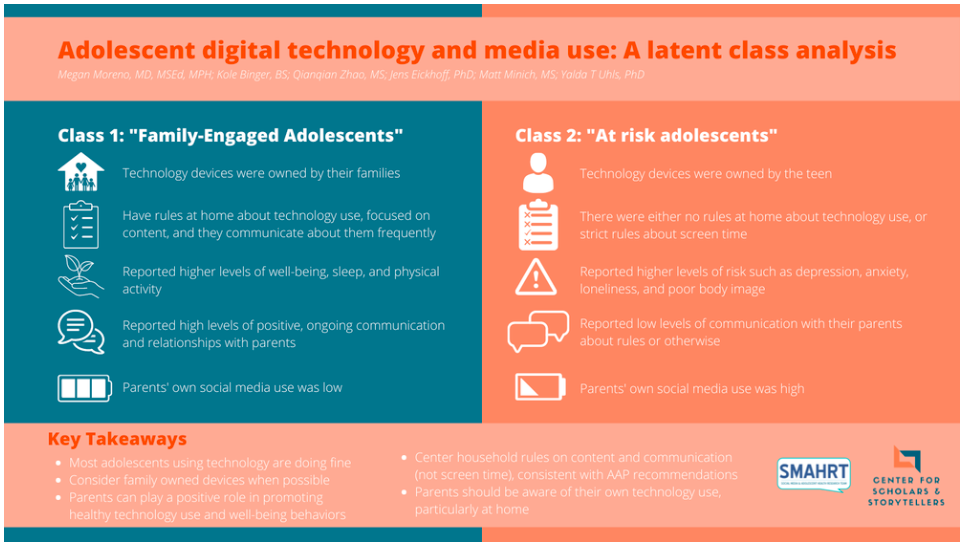

Aiding this viewpoint, a recent study with 4,000 teens age 13–18 and their parents (Moreno et al., 2022) identified two “classes” of risk for teen technology use and impact. Family-engaged adolescents reported better well-being, sleep, and physical activity. For these teens there was a tighter family connection in ownership and family communication, and parent technology use (specifically social media) was low. “At-risk” adolescents were those reporting higher levels of depression, anxiety, and poor body image; they were more independent in their technology access and parents’ social media use was high. As decades of research on families has observed, sociocontextual stress from living with poverty, unemployment, discrimination, and more creates conditions that pull parents away from their ability to fully attend to children’s needs.

Reports such as this help focus on the characteristics of teens for whom technology may be an added vulnerability, while the research into specific effects (for whom, which type of technology, under which conditions) continues.

Expanding our understanding of effects of technology and adolescent development

Groups like the American Academy of Pediatrics in the U.S. bundle recommendations for healthy adolescent technology use with those for children. These recommendations lean heavily on responsible use, use that is developmentally appropriate, and strong and constructive influence from educators and caregivers. An AAP article specific to medical connectivity with teens recommends applications that are user-centered in their design, address disparities in internet and device access, and are created with an awareness of challenges to data ownership, confidentiality, and data privacy. Their comments close by saying “Pediatricians should neither shun new technologies nor accept them wholeheartedly without review but always advocate for and consider the best interests of adolescents by carefully balancing the risks and benefits of using and recommending these technologies to optimize health outcomes, including physical, emotional, and social well-being, in this vulnerable population.”

The findings of the SMAHRT and Center for Scholars and Storytellers study described above underscore the heavy contributions by family in shaping teen’s technology use and outcomes. It recommends that devices are family-owned rather than individually owned, that households maintain patterns of communication about technology use, that parents are aware of their own use as they serve as models of behavior, and that a family focus on technology begins early in a child’s life.

James et al. (2017) and Hamilton et al. (2021) make the following research recommendations to better understand use of technology in general and applications like social media specifically:

- Individual differences in media use and its effects (who)

- Example research question: How does social media affect teens and communities differently on the basis of the intersection of different identities (e.g., race, gender) and context (e.g., home, peers, school, nation)?

- Timing and fluctuations of media use and its effects (when)

- Example research question: How do patterns of social media use fluctuate across individuals? Are teens using social media more at different times?

- How, where, when, and for whom does digital media use support positive well-being outcomes, social connectedness, and empathy?

- Media content, tools, functions, and meanings (what)

- Example research question: What specific social media experiences are teens having since COVID-19?

- What kinds of digital technologies promote patterns of use that support positive well-being, social connectedness, and empathy?

- Materials for studying media effects (how)

- Sample methods of interest: objective measures for social media; longitudinal, experimental, and intensive monitoring study designs

- Moving beyond correlational and self-report studies to gain more accurate insights into youth’s uses of digital media and their outcomes

- Including the wider lens:

- How can parenting, educational supports, and policy further support known positive well-being and social connection outcomes?

Young Adults and Technology

Development overview

The post-adolescence period is a dynamic one, perhaps best characterized as “launching.” After 18 years under direct care and supervision in the family home, most young adults transition to living separately and independently, fulfilling the expectations that they can accomplish the responsibilities and decision-making of adulthood and gain financial independence. The Urban Dictionary might boil this down to “adulting.” For many, this means post-secondary education for job training or a college degree, military service, taking a “gap” year to explore the world, moving directly into employment, and/or starting a family. Yet events can conspire to challenge individual plans. Consider the draft to military service in Vietnam in the late 1960s (this affected many young men, including the author’s brothers and cousins) or, more recently, economic shifts and COVID-19. At no time since the Great Depression have young adults lived at home in the U.S. in such high numbers (Arundel & Ronald, 2015; Fry, et al., 2020).

Arnett has characterized young adulthood as a unique period of human development. It overlaps with adolescence and adulthood, and is finely indicative of developmental transitions in identity, role responsibility, and cognitive and physical change post-childhood as they overlap from adolescence through to late adulthood (Arnett, 2007). In fact, the technological revolution has motivated a deeper understanding of this age period as unique from adolescence and full adulthood. Successful launching can result in a healthy sense of oneself as separate and unique, or “individuated.” In completing this process, the individual understands and forges relationships (especially with parents) that respect the sense of separateness, yet maintain the sense of belonging and connections.

Technology use

To a large extent, young adults age 18–29 continue technology use patterns established in their earlier years (Mollborn et al., 2021). So given teens’ interest in social media, gaming, and communication, it’s not surprising that young adults are more likely than their older adult counterparts to be active and comfortable with use in daily life, including schooling and for work (Vaterlaus et al., 2019). The majority of young adults (71%) use Instagram, which is significantly more popular than with older age groups. YouTube is popular with nearly all (95%) young adults, though high percentages of nearly all adult age groups appear to view YouTube (Pew, 2021; Schaeffer, 2021).

Among young adults, technology use varies when used for academic and non-academic purposes (Swanson & Walker, 2015). And variation occurs depending on who the young adult is talking to. A recent study by Lee and Dworkin (2022) identified four communication group types among digital media users connecting with mothers, fathers, and friends. Those with the friend-oriented pattern were associated with psychological well-being, and the multimedia group associated with stronger social well-being. Chapter 7 further discusses technologically facilitated relational dynamics in families with young adult members.

Young adults are a well-studied population when it comes to their technology use, given that many technology scholars are in higher education and have easy access to 18–24-year-olds who attend college and can be research participants. In part, this challenges our full understanding of the age group, as it skews towards a portion of young adults. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, 40% of those age 18–24 enroll in college (NCES, 2022). From a family perspective, studying young adults in college is beneficial to understand the role technology plays in family connectedness during a time of formation of a separate identity (e.g., Lee et al.’s 2009’s discussion of the “electronic umbilical cord”). Going to college represents a normative shift in context and in responsibilities that may encourage changes in technology use.

Mollborn et al. (2021) argue for a lifecourse perspective when exploring technology use in this age group, beyond assuming the continuation of behavioral patterns from adolescence. They determined that prior patterns of parenting had a significant influence on young adults’ technology use. Rather than having a discrete influence on frequency of technology use at a particular age (e.g., parent presence encouraging young adults to use technology more frequently for parent-child communication), parents’ greater impact came through from the ways their prior parenting messaging helped shape young adults’ emotional response to the use of technology. Indeed, the researchers found that context and demographic factors were quite malleable when examining predictors of use in young adulthood.

Impacts

Research generally supports technology’s role in aiding the relationship between young adults and their parents, grandparents, and siblings, and that multiple types of devices may be used in maintaining relationships (validating media multiplexity theory) (Hessel & Dworkin, 2018). Young adults appear to support their individuation by the strategic use of applications and devices that are both more and less familiar to parents to maintain family and other connections, respectively. Male and female college students with problematic mobile phone use show weaker relationships with their parents and their peers (Lepp et al., 2016). Still, Molvin et al. (2021) observe that methodologies used to understand technology’s actual impacts in this age group may need to be modified to allow for more individualized perspectives. They note, “As traditional role-based markers of adulthood have become more variable and difficult to attain, [methods may need to capture] self-focused understandings to achieve an internal sense of becoming adult.”

Challenges with cyber-victimization continue into young adulthood. Holmgren et al. (2020) examined experiences with cyber-victimization (i.e., being the recipient or victim of hurtful or mean online messages) in a sample of college and non-college young adults. One-fifth reported experiences with cyber-victimization, and within that group, significant relationships between cyber-victimization and lower levels of social and emotional wellbeing, and higher levels of externalizing and internalizing behavior. This suggests that when these experiences occur through online behavior, they can disrupt the young adult’s ability to form social capital.

Recommendations to date