7 Sustaining our Own Mental Wellness: Burnout, Vicarious Trauma, and Compassion Fatigue in a Rural Context

Melanie Abbott

Social work is a remarkable profession with many possibilities. The contexts in which we work, the changes we can help to effect, the individuals whose lives we have the opportunity to touch, are vast. But along with this wealth of possibilities comes some challenges including the mental health toll it can take. Hearing people’s traumatic stories, not having the appropriate resources to refer to, or being held back by organizational structures can all play a role in challenging even the strongest of our coping skills. Just because we may have, and even teach, the tools that can help maintain mental wellness does not mean we are immune to experiencing the effects ourselves. Not maintaining our own mental wellness can have far-reaching consequences including physical repercussions, damage to relationships, and even loss of employment. It is not just who we work with, however, that contributes to the impact the work can have on us. Location also matters. Working in rural and remote locations brings a different set of challenges as well as advantages from urban settings.

We know that the helping professions can be stressful. There is unpredictability requiring personal and contextual judgement rather than simplistic or formulaic solutions. We are also exposed to situations that the lay-person is not, seeing a side of humanity that not everyone does. Stress taps into our personal coping abilities and sometimes impacts our mental and physical health and relationships; however, stress is also temporary, and tends to increase or decrease in particular circumstances. Stress is sometimes just the tip of the proverbial iceberg when it comes to the mental health challenges social workers can face, meaning that it may be managed by doing, for example, self-care, engaging in social activities, meditating, and setting boundaries when it comes to workload. But sometimes it goes beyond “regular” stress and escalates to the point of interfering on a deeper level which can start to cause lasting changes in us. The causes of the mental health challenges we may experience professionally can come from job-related and client-related factors, which will be the focus of this chapter. For job-related factors we look at burnout; for client-related factors—how we respond to the trauma of others—we look at secondary trauma/secondary traumatic stress, vicarious trauma, compassion fatigue, and empathic strain.

When you hear the term “burnout,” what comes to mind? This often has a certain image connected to it: a person who is irritable, perhaps calling in sick more often, or snapping at someone who talks to them. The image is often of a person with piles of paperwork on their desk, perhaps coming in early or staying late, but still not catching up on their work. Now what about secondary trauma? What comes to mind when you read this term? The image might not be as clear, particularly to those who have not experienced it. If we focus on the word “trauma,” some of those symptoms might come to mind: jumpy, emotionally labile, poor sleep. How is this similar or different in a person who experiences the trauma first-hand (primary trauma) and the helping provider who experiences it second-hand? These experiences will be the focus of this chapter: how social workers are impacted by the work we do, both by the impacts of the job itself and the organization we work for, as well as how we cope with the trauma of others. Although many distinct terms are used to identify the nature of the mental health impacts this line of work has on individuals, for the purposes of simplicity and understanding, in this chapter we will focus on three: burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious trauma. The case examples provided to illustrate some topics are all fictional, but some are loosely-based on the author’s personal experiences, or composites of several social workers the author knows.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will have had the opportunity to:

- Learn about the concepts of burnout, compassion fatigue, and vicarious trauma.

- Explore some of the unique challenges of living and working in rural and remote locations.

- Understand why location matters by exploring some of the unique factors contributing to mental wellness or un-wellness among social workers in rural and remote settings versus urban ones.

- Recognize some ways that we, as social workers, can mitigate some of the above symptoms and promote our own mental wellness so we can be present with our clients, but also have an improved quality of life outside work.

Burnout, Compassion Fatigue, and Vicarious Trauma

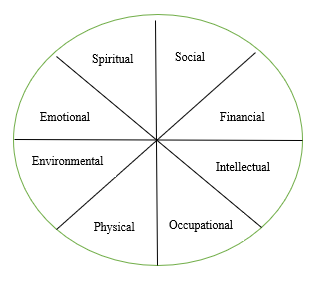

As social workers, we know (logically) that individuals need to have balance to be healthy. Consider a wellness wheel (Figure 1) which depicts where we direct our energies.

Figure 1

Example of a Wellness Wheel

If we put more focus in one or two areas and very little in others, our wheel will not roll very smoothly. If we are not careful, we may start to put more energy into work and our clients than we are putting into our personal lives, leaving our wheel unbalanced. Whether the overload is coming from job- or client-related factors, the impact on us will look different.

Let us now explore some definitions to put this idea of mental health of social workers into context.

Burnout

Burnout relates to organizational factors as opposed to the effects of working with a particular clientele. These are often connected to our lack of ability to effect change due to organizational limitations. Burnout is defined as “a syndrome conceptualized as resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed” as per the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11 as cited in WHO, 2019, para. 4). Maslach and Leiter (1997), pioneers in the research on burnout, conceptualized a multi-dimensional approach to burnout with six factors being contributors, although only one needs to exist to cause it. These six factors are workload demands, lack of control or autonomy over one’s work, lack of positive feedback or recognition for a job well-done, the workplace community (how much we can count on our colleagues to support us, how much trust we have in each other, social connections), fairness with respect to opportunity (for promotions and training, for example), and consistency of our work with our personal and professional values. According to these same researchers, burnout presents itself in three overarching symptom clusters, or dimensions: exhaustion, cynicism, and ineffectiveness. Exhaustion is more than just being tired, and is reflected in a complete lack of energy, both physical and mental, going to bed tired, and waking up tired. Cynicism, later termed depersonalization, is having a negative attitude to one’s job or career, which causes one to detach from it mentally, not believing in the work or one’s ability to effect change. Finally, ineffectiveness relates to the inadequacy one feels about their work and their ability to do their job, causing lack of productivity.

Maslach played a very important role by acknowledging the phenomenon of negative impact on individuals in the helping professions. She initiated a discussion of burnout in the 1980s and created the MBI (Maslach Burnout Inventory) to help assess for it (Maslach et al., 1996). Since the early days of burnout research and development, researchers have continued to explore the topic and challenge some of the concepts. For example, some newer research is questioning whether burnout is related to a depressive disorder rather than its own entity, since many of the symptoms overlap (Bianchi et al., 2020), where others have posed whether burnout may be more closely connected to post-traumatic stress disorder or anxiety disorders (Simionato & Simpson, 2018). The primary distinction seems to be that burnout symptoms have resulted from the job context as opposed to other life events. Currently, burnout is not its own diagnosis in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), but the symptoms may be seen in other diagnoses, as identified above. It is, however, included in the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (WHO, 2019), which looks at all diseases, not only mental illness. In this diagnostic system, burnout is seen not as a medical or mental health condition, but as an occupational phenomenon. The way the ICD-10 is organized, the letter at the beginning of the code signifies the category of illness, and then letters and/or numbers follow providing more clarity. For example, “F” relates to “Mental, Behavioral and Neurodevelopmental Disorders,” and this where one would find depressive and anxiety disorders. Burnout is not included in the “F” category at all. Instead, it is in the “Z” section, which is “Factors Influencing Health Status and Contact with Health Services.” It is further defined under a sub-heading (Z73) of “Problems Related to Life-Management Difficulty”. Some other diagnoses in this section include “lack of relaxation and leisure” (Z73.2) and “Inadequate social skills, not elsewhere classified” (Z73.4). The code for burn-out is Z73.0

To demonstrate one way in which burnout may present itself, the following example of “Margaret,” although fictional, presents a scenario that many who have been in a similar field may relate to:

Examples

After working for almost a year in a government health agency, Margaret started to notice that she was getting increasingly annoyed by the bureaucracy and the multiple layers of approval required before changes could be made. She experienced frustration as she was able to see first-hand how some policies were negatively impacting her clients, but little was being done by those in management to address these concerns. Colleagues started to notice that Margaret became angry even walking into staff meetings, just anticipating what “garbage” was going to be thrown at the staff “this time.” It even started to affect her attitude towards the job. If Margaret was given a new referral, she immediately became defensive, sharing questions such as “why do I get all the difficult cases?” and even “why doesn’t this person just help themselves?”

Questions for reflection:

- Would you say that Margaret is suffering from burnout, and if so, what symptoms or organizational demands lead to your decision? What other information would you want to have before you “diagnose” Margaret with burnout?

- Do you think Margaret could be experiencing depression? What symptoms lead to your decision?

- Looking at your responses to both questions 1 and 2, would you say that burnout is a type of depression, or do you view them as different?

Social workers in any facet of the profession have the potential to become impacted by organizational stress or through the experiences of their clients. Some research has been done into individual factors that may exacerbate some individuals’ risk over others. Simionato and Simpson (2018) completed a literature review looking into the demographics of burnout. Overall, it seems that although some demographic factors could contribute to burnout, it is more likely a combination of personal and occupational factors. There are some issues that impact the research on demographic aspects which makes it difficult to validate, including the possibility that people who experience burnout earlier in their career may leave the profession, thereby pointing to work experience being a factor where in reality, the people more prone to burnout may have left the profession earlier. The research has also suggested the possibility that some personality characteristics may make a person more prone to burnout, including neuroticism, rigid thinking styles, over-involvement with client problems, perfectionism, and being introverted. Lloyd et al. (2002) identify that people who are vulnerable and/or idealistic are drawn to the profession of social work, which could make them more prone to work-related stress based on these inherent factors. Apart from that, they found that “all the other stressors are contextual and relate to organisational and role deployment issues” (Lloyd et al., 2002, p. 262).

Compassion Fatigue

Whereas burnout is about the impact of organizational factors, compassion fatigue and vicarious trauma are about the impact on the professional when working with traumatized individuals. Compassion fatigue is how much care we give to others at the expense of ourselves and involves the professional themselves experiencing symptoms of trauma. Symptoms of trauma may include emotions of fear or anger, physical reactions of having a strong startle response (“jumpy”) and muscle tension, sleep disturbances, flashbacks, nightmares, and cognitive distortions also can be part of the experience. According to Figley (2002):

Compassion fatigue is defined as a state of tension and preoccupation with the traumatized patients by re-experiencing the traumatic events, avoidance/numbing of reminders persistent arousal (e.g., anxiety) associated with the patient. It is a function of bearing witness to the suffering of others. (p. 1435)

Figley initially developed the Compassion Fatigue Resilience Model in 1995, to demonstrate the risk and protective factors that either increase or decrease a person’s risk of developing compassion fatigue. This model acknowledges that empathy and compassion are cornerstone to a helping professional being able to be present and of benefit to their clients, but that with this comes risk to the helper themselves. It has evolved over time, and now includes thirteen variables:

- Exposure: it is necessary for the professional to have exposure to the client who is experiencing suffering.

- Empathic ability: The helper needs to also have the capacity to notice the pain of others.

- Empathic concern: The professional should have the interest and willingness to respond to the pain of others.

- Empathic response: The above three variables lead to the empathic response, or how much the professional engages and tries to help ease the suffering. The empathic response can be present in varying degrees depending to what extent the three contributing variables are present. If low, this can be a risk factor to developing compassion fatigue, along with the following four variables.

- Traumatic memories: of the therapist related either to their personal trauma or to trauma of other clients.

- Prolonged exposure to suffering: continued engagement with suffering individuals, with limited breaks.

- Other life demands: other events happening in the professional’s life outside of work.

- Compassionate stress: one experiences, which is the pressure to be compassionate, that the professional feels.

If certain protective variables are not in place, the factors listed above can lead to compassion fatigue, or if they are in place, can promote compassion fatigue resilience. The protective variables, which help to offset the risks, include:

- Sense of professional satisfaction: sense of accomplishment from the work

- Social support

- Detachment: taking a mental and physical break from the work; providing some distance between self and the client’s problems between sessions

- Self-care: defined by Figley and Figley (2017) as “the successful thoughts and actions that result in improving or maintaining one’s good physical and mental health, and a general sense of personal comfort” (p. 10).

- Compassion Fatigue Resilience: on a subjective scale from low to high, how resilient the care provider is to developing the symptoms of compassion fatigue. The lower the risk factors and higher the protective factors, the more resilient the provider will be.

Consider this hypothetical case scenario in the context of compassion fatigue:

Examples

Mark is a social worker in a hospice setting where he provides support to the dying and their families. After being in this position for a few years, where he was able to disconnect from his work at the end of the day, he lost his own mother to cancer. After that he started identifying much more with what his patients’ families were going through and found he had a more challenging time disconnecting. He was spending longer hours at work because “these families need me.” When he went home at the end of a shift, he was not able to engage with his family as much as before, “zoning out” when his children talked about their school day. He started numbing with alcohol and spent his “free time” reading about death and bereavement in an attempt to further understand what both he and his work-families were dealing with, taking away from time he could be spending with his wife and children.

Questions for reflection:

- What do you identify as being the risk factors to Mark experiencing compassion fatigue?

- What are his protective factors?

- If you were one of Mark’s support people, what suggestions would you make to him that could improve his compassion fatigue resilience?

A similar concept to compassion fatigue is empathy fatigue, which was coined by Mark Stebnicki in 1998. This condition refers to a professional who has an empathic relationship with another individual, and experiences symptoms similar to those of compassion fatigue or vicarious trauma. It is more a response of the professional’s own trauma history or stressors to the client’s stories, not a direct result of client traumas. It presents as exhaustion on all levels: mental, emotional, social, physical, spiritual, and occupational (Stebnicki, 2008). According to Stebnicki (2008), there are six main principles of empathy fatigue:

- It can occur at any stage of a person’s career, even early on, and may be dependent on the person’s age, personality, coping abilities, and personal and professional supports.

- The professional themselves do not always notice the onset or warning signs.

- If a professional is affected by empathy fatigue, they are not practicing ethically or competently, similarly to other forms of impairment.

- The effects are on a spectrum and do not follow the same path for every professional.

- The effects are often noticed by others, even if not noticed by the individual themselves, and therefore adequate clinical supervision and other professional support is necessary.

- It is the professional’s perception, not the client’s traumas or stressors, that contribute to empathy fatigue. This is to say that as individuals, we all have our own histories, and it is how our clients’ stories combine with our own responses that contribute to the amount of empathy fatigue we will experience.

Compassion fatigue and empathy fatigue share some commonalities, but there are also distinctions. One of the differences is based on the different definitions of “empathy” and “compassion.” Compassion is having a desire to help, while empathy is relating to the experiences of another. The more empathetic a professional is and the more empathy they experience and convey, the higher risk they are for developing empathy fatigue. Take, for example, the following difference: the social worker who uses a trauma therapy approach to assist a client with significant past trauma versus the social worker who empathically relates to a client who is going through a divorce and is struggling financially now as a single parent on a limited income. Stebnicki (2008) would suggest that the latter is at higher risk for empathy fatigue because of the extent to which their own personal emotional energy goes into relating to that client. Empathy fatigue is seen as more of a cumulative effect where compassion fatigue can have a more rapid onset.

Vicarious Trauma

Vicarious trauma is similar to compassion fatigue in that it evolves from secondary exposure to trauma through our clients’ experiences; however, unlike compassion fatigue it involves a change in the helper’s worldview and may or may not include trauma symptomology. This is a cumulative effect, building up over time (O’Neill, 2010a). Beyond the experience of compassion fatigue, vicarious trauma changes how an affected person views the world. This is, for example, when the social worker hears client stories of domestic violence and now believes that all relationships are unhealthy, or one who works with female survivors of sexual violence and now believes that men, in general, cannot be trusted. In the words of McCann and Pearlman (1990), “it is our belief that all therapists working with trauma survivors will experience lasting alterations in their cognitive schemas, having a significant impact on the therapist’s feelings, relationships, and life” (p. 136). This points to the intensity of the work we do as professionals in the business of working with society’s most vulnerable.

Vicarious trauma is not a new concept. The negative impact on helping professionals has been noted for a long time. A few decades ago, McCann and Pearlman (1990) developed constructivist self-development theory to explain the effect other peoples’ trauma can have on another person experiencing it vicariously. This theoretical model essentially says that we all have our own ways of viewing the world, and when these views are challenged by having conflicting information provided to us through experiences, directly or indirectly, our worldview changes. If we believe the world to be a generally safe place but then hear someone’s experience of being a victim of violence, this can affect how we perceive the world as well. This is also why vicarious trauma tends to be a gradual effect. Hearing one traumatic story might not make a person believe in the general lack of compassion in humans but hearing story after story with a similar theme can.

The following fictional scenario of “Sheryl,” demonstrates how vicarious trauma can develop and affect the individual:

Examples

Sheryl is a social worker in a sexual violence program at a community-based agency. After working with several women who had been abused and hearing intimate details of the assaults and the ongoing impacts on them, Sheryl began to lose her trust in men. Where previously she had been social, going out with friends and on the occasional date, she now began to isolate and removed her online dating profile. She no longer trusted men and did her best to not encounter them alone. Even if she were on an elevator and a man got on, she would often get off, even if it was not her floor.

Questions for reflection:

- How does this presentation differ from the examples of burnout and compassion fatigue?

- One marker for the development of vicarious trauma is the change in the individual’s worldview. How do you think the mental health consequences of Sheryl’s job would have been similar or different if Sheryl had previously been the victim of intimate-partner violence herself?

Impacts on Mental Health in a Rural/Remote Context

With the research showing that burnout and other work-related stress is more related to organizational factors than individual ones, let us now turn our attention to some of the impacts of mental health strain specifically through a rural/remote lens, as the working conditions in this context are often different than in urban settings. Consider the following scenario:

Examples

You are a social worker who has been hired by a non-profit agency to provide support to families who have been exposed to domestic violence. Your primary role is to provide counselling to women who have been victims of abuse. In this office it is just you and one other social worker who is also in the role of supervisor. You begin offering counselling support to a woman after receiving a referral from the local child protection agency, who had become involved because the couples’ three children, ranging in age from four to eight, have witnessed some of the violence, which always reportedly occurs when one or both parents is using substances. Although your role is to work with the woman, the child protection agency has set a requirement for the husband to get counselling for his anger and for both parents to address their substance use issues. As well, the two eldest children are demonstrating some acting-out behaviours at school. As this particular community has no programs for men, nor for addictions, and the school does not have a counsellor on-site, you are asked to take on all these roles: domestic violence counsellor, anger management counsellor, couples’ counsellor, children-who-witness abuse counsellor.

This is not necessarily unrealistic in rural social work. One person may wear many hats when it comes to service provision. As you think about this scenario, imagine this is you and consider the following:

- How might you feel about being asked to take on more than you had agreed to when you took the job?

- Think about the ethical implications and consider how you might respond: maintain your boundary of remaining within your job description even if it means the family does not receive all the support they need to stay together, while limiting your stress level, or offering all the various supports while potentially placing increased pressure on you.

- Now think about this scenario from the perspective of the child protection social worker who is also doing their best to protect the family and keep them safe and together, having limited resources to refer out to. How might it affect your practice if there is no one available to offer the various supports? How might you help the family to be safe if you are limited in the services you can access?

This is often the reality of working in a small or remote community where the resources are limited. That might be okay if you are a seasoned social worker who has experience or at least feels comfortable and competent working in all these areas, or if this is the only family you have on your caseload and you have access to training to support you, but these conditions are rare.

Rural agencies often hire new social workers who are seeking experience at the beginning of their careers. That experience can be overwhelming given that there is also likely little support offered. Refer to the beginning of this chapter and the contributors to burnout. What do you notice? Which of the six factors do you identify when you look at the above scenario? Quite possibly a high workload demand given that you are one of only two social workers and the other has other responsibilities to attend to. You also have limited control over your role since you are being called upon to do more than you were hired to do. Depending on your relationship with your supervisor and how over-worked they are, you may or may not receive much positive feedback, and support you receive from colleagues is limited by the small workplace community. What you are being asked to do may also not be consistent with your personal values. If you accepted this role to support victims of domestic violence, it may be outside of your comfort-zone to be asked to work with the perpetrator as well. In their review of the literature around social work and burnout, Lloyd et al. (2002) identify that the general population sometimes does not understand the role and work of social workers, resulting in lack of support for their expertise and experience, which may be a cause of burnout. This review refers to several authors in saying that people often think social work is just being nice or doing the things “that anyone can do” (Lloyd et al., 2002, p. 257). The issue of role ambiguity is prevalent in the literature as a contributing factor to burnout. In rural or remote locations, where resources are limited, there is the issue of roles not being understood but also, due to the lack of other referral sources, social workers may be asked to take on duties outside the scope of what they have been hired to do, forcing them to become a generalist practitioner. Riebschleger et al. (2015) look at the matter of child protection social work in rural communities and identify many of the same issues: lack of resources and minimal funding, all in the context of higher rates of poverty and substance abuse as is common in rural and remote areas.

There are several factors that social workers in rural/remote workplaces need to contend with that are not necessarily present to the same extent in urban locations. O’Neill (2010a) identifies some of these factors as “increased need for flexibility, personal independence and creativity, risk of professional and personal isolation, and limited community resources and lack of referral sources” (p. 3). Much as our hypothetical social worker experienced, they needed to become generalists because other services were absent. The circumstances in which burnout can occur include workload demands and lack of control or autonomy, so being expected to do more than you initially agreed to, and sometimes in situations of not feeling competent in some areas, will have a negative impact. It could be argued that this is an even higher risk for social workers in remote settings where there are fewer people doing the work. Riebschleger et al. (2015) refer to research, although based in the United States, that talk about the strongest predictors of child welfare workers leaving rural work, which include low levels of work-life balance and not feeling effective or satisfied in their jobs.

These differences between working in rural and remote locations versus urban ones also contribute to social workers experiencing burnout or secondary trauma differently. As Linda O’Neill (2010a) identifies, “informal reports suggest that northern practice may be detrimental to longevity in the field for mental health practitioners, especially those who come from outside northern communities” (p. 2). Part of the reason for this may be found in some of the issues already identified, in terms of lack of anonymity and isolation both personally and professionally. However, the nature of the work is often different in these locations based on the clientele and presenting issues. When you look at the make-up of Canada and which communities tend to be considered rural or remote, much of the population in these areas is Indigenous. We know the long-standing history of the trauma that Indigenous people have experienced in Canada and the inter-generational effects today. According to Canadian Census data collected between 2011 and 2016, suicide rates among Indigenous people in Canada are three times higher than non-Indigenous people, and nine times higher among the Inuit (Kumar & Tjepkema, 2019). High levels of primary trauma inevitably lead to high levels of secondary trauma for those trying to help.

Social factors can also contribute to some of the negative impacts on a social worker’s mental health, whether that be cultural norms or socio-economic influences such as high rates of poverty or homelessness. These cause the potential for value conflicts between worker and location. Consider this example of “Penelope,” which demonstrates value conflicts along with the experience of perceived inability to help, or to effect change, in a setting in which it is difficult to separate from this reality even during non-working hours. Although fictional, Penelope’s experience is not uncommon, particularly for social workers working in communities quite different from their own:

Examples

Penelope is a social worker in a remote northern community working in a mental health setting. She has had several female clients who are experiencing domestic violence. Not only does she experience hopelessness and frustration at the lack of supports available for these women in the community, but she also sees how few options there are for women living with abusive partners. Homelessness rates are high, so it is not an option for many of these women to leave their partners and move out on their own. Unemployment rates are also high, so financially it is not very feasible for women to branch out on their own. Often when she goes out in the community, Penelope notices women with black eyes and bruises on their arms, and she is disturbed by how domestic violence seems to be normalized to the extent that women often do not even try to hide what is happening behind closed doors.

Question for reflection:

- When you read the above scenario, did you assume Penelope was from this community, or from elsewhere? Why? How do you think her response would be different if she were from this community or from away?

There are two types of social workers working in rural or remote communities: those who are from the community, and those who are not. Both come with their own sets of challenges. Moving away from what one is used to and into a completely new setting without the predictability that comes with it can be an adjustment for anyone. Moving to a community with perhaps a different culture, customs, and lifestyle than they are used to brings a new set of challenges. Many of Canada’s remote communities have high Indigenous populations. Although this cross-cultural exchange can be exciting and provide new opportunities to both the professional and the community, there are also potential challenges in being viewed as an outsider. For instance, the professional may not understand the culture and idiosyncrasies of the community dynamics, channels to achieve change, politics, customs, and history. Sometimes professionals moving into a community are afforded opportunities not provided to the locals; for example, housing provided to professionals can be a barrier when many members of the community struggle with housing instability, or access to better-paying jobs because of the opportunity to have gained an education. This contributes to the “outsider” effect and assumptions based on ethnic stereotypes. Navigating these systems and differences can cause a lot of stress. Take the example of “Steve,” who portrays the experience of guilt over the allocation of resources and how this is viewed differently by the different populations involved:

Examples

Steve decided to move out of the rat-race of city-living and give living and working in a northern community a chance. This community was desperate for qualified social workers, so housing was provided, albeit at a cost. Once Steve got settled in his home, at his job, and started making some social connections, he started to notice comments being put on local social media platforms about the housing crisis in the community and the perceived unfairness of outsiders getting housing when so many of the local residents struggle with homelessness. This led to Steve feeling like even more of an outsider and contributed to feelings of guilt over his comparative resources.

Questions for reflection:

- Even though his living situation is not directly work-related, can this still potentially have a negative impact on Steve’s ability to do his job effectively?

- What ways can you think of that Steve’s mental health might be negatively impacted?

- What are the ethical implications, and how might Steve address the situation if called out on this privilege by a client?

Being a member of the community and transitioning to a different role is also a challenge in rural settings in that the social worker may be related to or know the community members, who may become their clients, on a more intimate basis, causing changes in their relationships and pose issues of confidentiality. This brings up some ethical dilemmas, particularly with respect to confidentiality and dual relationships, which can exacerbate work stress, particularly if combined with a lack of supervision opportunities. There is also the added component of a shared trauma history between professional and client (O’Neill, 2010b) which the worker may need to do some personal work on to promote healing in themselves so as not to be further triggered in their work setting. Consider the following fictional scenario of “Susie”:

Examples

Susie, an Indigenous woman, was the first member of her family to go to university. She graduated with her social work degree and was excited to return to her community after 4 years away to work and to make a difference in the social circumstances there. She started working at an organization whose focus was keeping families together, through providing counselling services, advocacy, and supervised visitation upon the referral of the child protection agency. Shortly after she started there, her parents and brother organized a gathering to celebrate her graduation and invited members of the community. Susie was surprised to find that she received a cold reception from some people who believed that Susie was helping to reinforce systems of keeping families apart. This was particularly hurtful because, as having being part of the foster care system herself for a brief period as a child, Susie believed strongly in keeping families together wherever possible, while also recognizing that this is not always what is best for vulnerable children.

Questions for reflection:

- Why do you think the community is wary of Susie retuning to the community, even though they know her? What are they afraid of?

- How might Susie win over her community again?

- Considering the history of colonization in Canada among Indigenous populations and the impacts of intergenerational trauma, how might the community members have treated an “outsider” differently than they treated Susie?

Confidentiality and anonymity are factors that are more likely to come up in smaller communities where there is a higher likelihood of seeing clients in your personal time. Trying to navigate confidential situations can be challenging: do you acknowledge the client you see in public and risk “outing” them as a client? Or do you ignore them and risk their feeling rejected? And what about if you learn something about your client outside of the office space that may need to be addressed in it? For example, you are working with a client on their alcohol addiction and then see them drinking at the local pub. How does one navigate this? Addressing this potential in the professional setting, discussing this possible situation beforehand, can prevent awkwardness later on. Is keeping to yourself, then, the best option to prevent these possible circumstances? O’Neill (2010b), in her research among rural helping professionals in northern BC and the Yukon territory, identifies the balance sometimes needed when working as an “outsider” in a rural/remote community in that staying an outsider will have you missing out on a lot, but being too involved in the community may lead to more dual relationships. Graham et al. (2008) bring to attention the issue that it is more challenging to prevent dual relationships in smaller settings but that there is a cost to not even trying: “If practitioners were to take seriously the view that all dual relationships must be avoided completely, they would most likely not be able to practice in such settings” (p. 400). It is about balance: communities need social workers (and all professionals), so if this means there will be some overlap in personal and professional relationships, the benefits likely outweigh the challenges.

A significant component of good mental health is placing energy in various areas of one’s life as opposed to just one or two, which includes work-life balance. In smaller communities, a social worker’s life can be impacted even on their personal time, which can affect how they choose to do their self-care, a protective factor against the negative impacts on their mental health. As mentioned, lack of anonymity, seeing clients in the community, even having people know where you live are often realities. Any hobbies the rural social worker enjoys participating in may pose challenges because of the small number of people to draw from who may share the same interests. Becoming involved in the local play production, joining the community band or choir, attending an arts or language class: these are all potentially-awkward situations for the social worker to navigate. It is difficult to fully relax and enjoy an activity if one believes they might be under scrutiny from others. Depending on the role we play when our social work hat is on, physical safety may be an issue; think of child protection social workers who may have had to intervene with a family who is very angry at such intervention, or a mental health social worker who phoned the police to check on a patient at home. The self-care practices, the things we do to reduce our stress and to off-set the negative impacts of stress, are therefore sometimes hindered.

Consider this example of a social worker whose personal time was affected by an ethical dilemma:

Examples

Melissa is a child protection social worker. She has been working with a family where domestic violence is the primary concern. As a result, there is an order in place stating that the father cannot have unsupervised access to the children and any contact must have the pre-approval of the social worker. One evening while Melissa is waiting in line at the local swimming pool, she notices the family in line ahead of her: both children and both parents. Although there on her own time to participate in a healthy activity for her own physical and mental wellness, Melissa considers her ethical and professional responsibilities. She ends up phoning the after-hours child protection line and being directed to intervene, spending the rest of her evening making alternative plans for the children after the breech of the order. After this experience, Melissa is hesitant to go public places for a long time.

Questions for reflection:

- Should Melissa have ignored this situation, or pretended she did not see the family? If you were her, how would you have felt if you ignored what you saw? Refer to the Canadian Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics to guide your decision. Which of the values are most relevant?

- Is this situation as likely to occur in a more urban setting?

- Think for a moment about how comfortable you would be in the above scenario and how you might handle it. Is this something you are prepared to face? Or is it more important to you to have your anonymity and a greater distinction between work and personal life.

Stress and burnout impact the individual social worker, but it also has impacts on the system at large. O’Neill (2010a) provides some context as to the vastness of the remote locations in Canada and brings to light the issue of limited resources, meaning more stress on the people doing the work. Preventing burnout and mitigating the effects of secondary trauma is essential in trying to retain the perhaps few professionals present, and to prevent the high turnover rates often seen in rural and remote environments. In their literature review on the impacts of burnout on mental health professionals, Morse et al. (2012) point to several negative outcomes including neck and back pain, sleep problems, depression, anxiety, substance use, and other problems related to the circulatory, respiratory, and digestive systems. From an organizational perspective, these authors found that employee burnout has a range of negative impacts. Not surprisingly, employees who are burned out will be away from work more often (absenteeism), are more likely to leave their jobs; the resulting employee turnover/retention problems can be costly to the organization. These problems also affect the quality of services clients receive as the burned-out employee may not put as much effort into their work and may not adhere to best-practice standards.

We see that the job impacts on the social worker can differ for multiple reasons, including individual factors, the organization and organizational culture, and location (rural vs urban). Whether or not we are from the community in which we are working will make a difference, as is how involved or distant we are from the community members and activities. Because no two social workers are the same, nor every community or organization, there is no “right way” to mitigate the negative mental health effects, so finding what works for the individual is essential.

Promoting Mental Wellness

We have seen how working in relative isolation can negatively impact our mental health, but what can be done about it? The motivation should be high for us as helping professionals to maintain our mental well-being not only for ourselves but also so that we can show up for the people we serve. In their book on trauma stewardship, Laura van Dernoot Lipsky and Connie Burk (2009) acknowledge that “people who are working to help those who suffer, or who are working to repair the world to prevent suffering, must somehow reconcile their own joy- the authentic wonder and delight in life- with the irrefutable fact of suffering in the world” (p. 16). In other words, be cautious not to feel guilty for enjoying your own life while others are experiencing distress. Everyone has their challenges. Just because one person seems to be struggling more than you does not diminish the depth of your own challenges or successes. You need to avoid comparing yourself to others as you move forward through your career in social work.

As we have seen, mental health is an issue that has consequences for the organization as well as the individual, so exploring changes that can be implemented at both levels is crucial. Organizations can be agents of change, but change can be slow to implement if it is even recognized in the first place. Depending on the size of the organization and the distance between decision-makers and workers on the front-line, change may be easier or more challenging. A problem cannot be solved if no one knows about it, so speaking up about our areas of struggle can be a great place to start. For example, having conversations about workload or opportunities for training to feel more competent, as well as advocating for adequate orientation on the job and addressing role ambiguity.

Some research suggests that higher levels of social support (personal and professional) increase compassion satisfaction and decrease burnout among helping professionals (Killian, 2008). In fact, this researcher discovered that helping professionals working in a team environment had higher job satisfaction and less psychological stress, and that the more contact the helper has with traumatized individuals in a week, the lower their compassion satisfaction. If support and a team-based working environment are mediating factors in causing burnout from workload demands, then those working in remote locations with few co-workers are missing out on this benefit. Developing a system of support for social workers in such settings can reduce the potential negative impacts of workload demands. Manning-Jones et al. (2016) identify three primary factors to promoting mental wellness among helping professionals, social support being one of them. All types of support—peer, family/friends, and professional—were shown to be of benefit. The other two processes noted by these authors are self-care and humour. The emphasis in the research on the importance of support, both personal and professional, in maintaining mental wellness stresses the need for adequate supervision. Unfortunately, in rural settings where agencies tend to have fewer staff, the level of supervision a social worker gets is not always adequate. Morse et al. (2012) identify some leadership strategies that can support social workers’ mental wellness. This includes helping to reduce employee feelings of inequity by offering opportunities to meet the needs of the individual as well as the organization. As burnout is highly related to organizational factors, these authors also identify literature that addresses organizational strategies to reduce burnout, including increasing social support as well as regular supervision, both formal and peer; allowing employees to be a part of decision-making about their roles; reducing job ambiguity; decreasing workloads; and training supervisors about communication and the importance of all these factors.

Training is another issue that arises, as competence in the field contributes to better mental health and a belief in one’s power to affect change. Adams and Riggs (2008) explore some of the factors that lead to higher risk of vicarious trauma among therapists, and one of their findings is that therapists with less experience tend to have higher rates of symptoms of trauma in themselves. They argue for better training of individuals who will be doing the work, and not just a one-day workshop. Because in a rural or remote setting social workers cannot always control the type of work they end up doing or the clientele they see, accessing supervision right from the start is imperative to maintaining their wellness and their perseverance in the profession.

We cannot rely solely on organizations to change or just hope that we have a supervisor who has the time, energy, and experience to provide what we need. From an individual perspective, there are some actions we can take to put our mental wellness in our own hands. Before even moving to the community, it helps to do some research to familiarize yourself with it, including the culture (which includes challenging your own cultural biases), what resources are available, how decision-making occurs, historical and intergenerational trauma, and socio-economic concerns. Van Dernoot Lipsky and Burk (2009) note that our own personal history can impact our response to the work we do. If we have our own trauma history, we may be more, or differently, impacted working with a particular traumatized population than someone without that lived experience. Therefore, considering why you are choosing the work you do and taking regular stock of whether this continues to be a positive choice for you, may assist in either continuing in accessing supports of your own, or even making the decision to transition to another stream of work.

In their literature review on burnout, Morse et al. (2012) look at studies focused on the reduction or prevention of burnout among mental health professionals. Some of the interventions they identify are recognizing training needs and then accessing such training, both strategies to help their mental health clients/patients, and cognitive behavioral strategies for managing their own symptoms, improving coping skills, mindfulness, meditation, and gratitude. Other authors have noted the same. Cohen and Collens (2013) completed a metasynthesis of the research on post-traumatic growth, looking at the themes that arise for trauma therapists. One of the themes identified was ways of coping with the traumatic information professionals hear from their clients. In addition to some organizational factors, many of which have already been identified in this chapter, they found some individual coping skills including exercise, healthy eating, rest/meditation, taking holidays, socializing, watching movies, political activism, keeping a sense of humour, and psychotherapy. They also highlight the strategy of finding ways of detaching from work during personal time. Similarly, Manning-Jones et al. (2016) have found that social support, self-care, and humour are three coping strategies to offset the effects of secondary stress.

Professional identity, especially seeing oneself as helper, is also noted in the literature as promoting self-care and longevity in the field. Van Dernoot Lipsky and Burk (2009) talk about trauma stewardship and use a model of five directions to encourage us to do a daily reflection on a few areas, including asking yourself what is your “why” for doing the work you do, focusing on what is within your control, developing and maintaining social connections, having balance, and practicing mindfulness. In doing this, we can be assured that where we are choosing to put our professional efforts continues to be in line with our values and capabilities and puts the onus and control on ourselves to either maintain or to change tack if we recognize the need. As humans, we all have limitations. Ignoring these and trying to push forward at the expense of our own mental and physical health will do nothing to help neither us nor those we are trying to serve. This connects to having belief in the work we do (O’Neill, 2010b). What keeps us going even on the most challenging of days and with the most challenging of clients is the belief and hope that change is possible. Consider this example of Mary, who has put a lot of effort toward ensuring she becomes a community member, not just a professional outsider:

Examples

Mary started working in a predominantly Indigenous community directly out of finishing her Bachelor of Social Work degree. She was eager to get into the workforce and begin what she was sure would be a long career as a helper. Although faced with some initial challenges with being accepted into the community, and some embarrassing experiences in which her ignorance of the local culture showed, she persevered. She was active in the community and never passed up an opportunity to attend a cultural event. She continued to have her struggles as the nature of her job was not always conducive to having people like her, but her connection to the community re-enforced why her work was so important.

Questions for reflection:

- What do you think contributed to Mary’s success in integrating into the community?

- What do you think contributed to some of the challenges Mary experienced at first?

- From the perspective of community members, how might they have thought about Mary immersing herself into their community and culture?

- How might Mary’s experience have been different if she was trying to immerse herself in an urban community?

Valent (2007) identifies eight possible survival strategies in response to trauma: “fight, flight, rescue/caretaking, attachment, goal achievement/assertiveness, goal surrender/adaptation, competition/struggle, and cooperation/love” (p. 4). O’Neill (2010a) points to four of them (flight, cooperation, attachment, and acceptance) as being most utilized by mental health practitioners living in the north. Flight– from the commonly-acknowledged “fight/flight/freeze” response to perceived danger–is escaping from a potential threat. In the context of coping with rural social work, this response manifests in several ways: isolation from society, not participating in the community other than going to work; leaving the community on weekends or taking vacations away; or leaving the community entirely. Cooperation is just as it sounds, meaning working together without competition, or pooling resources. Along with support, cooperation is vital to working in isolation, especially when there are limited resources. Valent (2007) argues that “loving relationships and social networks may protect not only against cardiovascular disorders but also against a variety of traumatic stress and other disorders” (p. 11.) Attachment, as we have already explored, is an important part of being a human. We do not live or thrive in absence of human connection. Living in isolation often necessitates an even greater need for attachment to our support system. Acceptance is what Valent (2007) refers to as goal surrender or adaptation: “it demands delaying or surrendering goals, grieving losses, and adaptation to new circumstances” (p. 9.) From everything we know about working in isolation, this makes sense. If we try to hold on to the way things were when we were in an urban setting with more resources and supports, we will quickly get dragged down. Valent (2007) talks about the grieving process that sometimes comes when we recognize the need to adapt to a new way of being and working.

There are some challenges to working in rural or remote locations that urban centres do not necessarily have to contend with, but the news is not all bad. There are many benefits to working in rural communities. Riebschleger et al. (2015) point out that rural practice may involve more independence and collaboration with other agencies, including multidisciplinary teamwork, and engaging with community members on a formal and informal basis leading to developing good working relationships. Focusing on the positives that can arise from working in smaller and remote communities can provide an attitude that will be beneficial in maintaining mental wellness.

There is also some good that can come out of exposure to the types of trauma social workers experience. Some research indicates that people who have experienced trauma, including those who experience it vicariously, can be positively impacted by it. The term posttraumatic growth has developed from this, which is “the process of developing new strengths, stronger relationships, expanded coping mechanisms, and psychological understandings that incorporate trauma experiences” (Regehr, 2018, pp. 7-8). Some benefits can be seen such as increased sensitivity, compassion, and insight; an increased appreciation for the resilience of the human spirit; and an increased sense of the precious nature of life (Arnold et al., 2005 as cited in Regehr, 2018, p. 8).

Professional and vicarious resilience occur when those who work with vulnerable populations thrive in this high-stress environment (Newell, 2018). According to Hernandez et al. (2007), who developed the concept of vicarious resilience, the resilience of people who have experienced trauma is felt by the helper. Those whose work does not expose them to people in their most vulnerable state may never feel the joy of seeing a person finally overcome an obstacle they have been struggling with for a long time or feel the satisfaction of helping someone see themselves or someone else in a new light, as in the case of “Philip” below:

Examples

Philip is a child protection social worker. He has been working with a family over the past couple of years. Through that time there have been some successes but also some challenges. Twice he had to remove the children and place them in temporary foster care arrangements. After the last removal, the single mother went away to a residential addiction treatment program and successfully completed it. She has been sober now for 4 months and has found employment and stable housing. The children are back living with her, and Philip is preparing to close the file after one final home visit. Philip reflects on the last couple of years and feels a sense of happiness and hopefulness for this family.

A question for reflection:

- One possible concern for professional helpers is putting our professional self-worth in the successes of our clients. That is, believing that if our clients are not progressing, this is an indication that we are not doing a good enough job. What are the risks in this for both the social worker and the client? As you prepare to move forward into a career in social work, what ideas do you have to prevent this from happening to you?

Conclusion

Take a moment to make a list of all your hobbies and interests outside of work or school. Include the places you like to go in your community, the people you socialize with, the events you like to go to, the sports or other organized activities you enjoy. Now imagine yourself working in a community with a small population, perhaps one that is also isolated with no big cities nearby. Knowing what you do now about maintaining your own mental wellness as a social worker in such a setting, how do you see these activities possibly being impacted? Would you feel comfortable going to all the places you identified? How might your choice of social contacts change in this context?

As a social worker in a small community, you do not have the luxury of anonymity. You are likely to face issues of dual relationships in that your activities may overlap with those of some of your clients. The more prepared you are for this happening, the more you can plan. Balance is essential. Finding an equilibrium between being overly visible in the community, attending every social event, joining every organized sport or activity versus staying in your home and only reading books and watching television when you are not at work will help you. Develop and strengthen your personal support system; arrange regular phone calls or Zoom dates with friends and family. Build supervision opportunities into your practice. All of these are factors within your control, and the more open you are to recognizing and accepting these factors as well as your limitations, the more prepared you will be to survive professionally in a place where you do not necessarily have all the resources available to others.

Finally, as a reminder to your “why,” to help keep in mind why you continue to stick with it (whatever “it” may be):

The Boy and the Starfish (Loren Eisley1)

One day a man was walking along the beach when he noticed a boy picking something up and gently throwing it into the ocean.

Approaching the boy, he asked “What are you doing?”

The youth replied, “Throwing starfish back into the ocean. The surf is up and the tide is going out. If I don’t throw them back, they’ll die.”

“Son,” the man said, “don’t you realize there are miles and miles of beach and hundreds of starfish? You can’t make a difference!”

After listening politely, the boy bent down, picked up another starfish, and threw it back into the surf. Then, smiling at the man, he said “I made a difference for that one.”

Activities and Assignments

- Create your own self-care/wellness plan. Prevention is better than intervention, so developing some self-care strategies now, at the beginning of your career, can go a long way in the mitigating of further problems. Keep in mind the wellness wheel format: how can you maintain or improve wellness in all facets. Refer to this at the end of your practicum and again a few months into your first job as a social worker and see how well you are maintaining it; make any changes as needed.

- Search and complete the Professional Quality of Life Scale – The ProQOL 5 Self-Score (English) – on the ProQOL: Professional Quality of Life website in the ProQol Measure & Tools section to see how you rate on levels of Compassion Satisfaction, Burnout, and Secondary Traumatic Stress. If you are currently in a work or practicum setting, this exercise could provide insight into how your work is currently affecting you. Keep your scores and return to this later, once you have been working in the field of social work for a while, in order to note any shifts.

Additional Resources

- McCann, L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131-149.

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual review of Psychology, 52, 397-422.

- Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Valent, P. (2007). Eight survival strategies in traumatic stress. Traumatology, 13, 4-14.

- Van Dernoot Lipsky, L., & Burk, C. (2009). Trauma stewardship: An everyday guide to caring for self while caring for others. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

References

Adams, S. A., & Riggs, S. A. (2008). An exploratory study of vicarious trauma among therapist trainees. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 2(1), 26-34.

Arnold, D., Calhoun, L.G., Tedeschi, R., & Cann, A. (2005). Vicarious posttraumatic growth in psychotherapy. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 45(2), 239-263.

Bianchi, R., Schonfeld, I. S., & Verkuilen, J. (2020). A five-sample confirmatory factor analytic study of burnout-depression overlap. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 76, 801-821.

Cohen, K., & Collens, P. (2013). The impact of trauma work on trauma workers: A metasynthesis on vicarious trauma and vicarious posttraumatic growth. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 5(6), 570-580.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Psychotherapy in Practice, 58(11), 1433-1441.

Figley, C. R., & Figley, K. R. (2017). Compassion fatigue resilience. In E. M. Seppälä, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, and J.R. Doty (Eds.), The oxford handbook of compassion science. Oxford Press.

Graham, J. R., Brownlee, K., Shier, M., & Doucette, E. (2008). Localization of social work knowledge through practitioner adaptations in Northern Ontario and the Northwest Territories, Canada. Arctic, 61(4), 399-406.

Hernandez, P., Gangsei, D., & Engstrom, D. (2007). Vicarious resilience: A new concept in work with those who survive trauma. Family Process, 46(2), 229-241.

Hudnall Stamm, B. (2009). Professional Quality of Life: Compassion Satisfaction and Fatigue Version 5 (ProQOL).

Killian, K. D. (2008). Helping till it hurts? A multimethod study of compassion fatigue, burnout, and self-care in clinicians working with trauma survivors. Traumatology, 14(2), 32-44.

Kumar, M. B., & Tjepkema, M. (2019). Suicide among First Nations people, Métis and Inuit (2011-2016): Findings from the 2011 Canadian census health and environment cohort (CanCHEC).

Lloyd, C., King, R., & Chenoweth, L. (2002). Social work, stress and burnout: A review. Journal of Mental Health, 11(3), 255-265.

Manning-Jones, S., de Terte, I., & Stephens, C. (2016). Secondary traumatic stress, vicarious posttraumatic growth, and coping among health professionals; A comparison study. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 45(1), 20-29.

Maslach, C. (2003). Job burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 189-192.

Maslach, C., & Leiter, M. P. (1997). The truth about burnout: How organizations cause personal stress and what to do about it. Jossey-Bass Inc.

Maslach, C., Jackson, S. E., & Leiter, M. P. (1996). Maslach Burnout Inventory (3rd ed.). Consulting Psychologists Press.

McCann, L., & Pearlman, L. A. (1990). Vicarious traumatization: A framework for understanding the psychological effects of working with victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 3(1), 131-149.

Morse, G., Salyers, M. P., Rollins, A. L., Monroe-DeVita, M., & Pfahler, C. (2012). Burnout in mental health services: A review of the problem and its remediation. Adm Policy Men Health, 39(5), 341-352.

O’Neill, L. (2010a). Mental health support in northern communities: Reviewing issues on isolated practice and secondary trauma. Rural and Remote Health, 10(2).

O’Neill, L. (2010b). Northern helping practitioners and the phenomenon of secondary trauma. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 44(2), 130-149.

Regehr, C. (2018). Stress, trauma, and decision-making for social workers. Columbia University Press.

Riebschleger, J., Norris, D., Pierce, B., Pond, D. L., & Cummings, C. E. (2015). Preparing social work students for rural child welfare practice: Emerging curriculum competencies. Journal of Social Work Education, 51(sup2), S209-S224.

Simionato, G. K., & Simpson, S. (2018). Personal risk factors associated with burnout among psychotherapists: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74, 1431-1456.

Stebnicki, M. (2008). Empathy fatigue: Healing the mind, body, and spirit of professional counselors. Springer Publishing Company, LLC.

Valent, P. (2007). Eight survival strategies in traumatic stress. Traumatology, 13, 4-14.

Van Dernoot Lipsky, L., & Burk, C. (2009). Trauma stewardship: An everyday guide to caring for self while caring for others. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

World Health Organization. (2019). Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”: International classification of diseases.

“a psychological syndrome that involves a prolonged response to stressors in the workplace” (Maslach, 2003, p. 189).

The result from when an individual “who work[s] with victims… experience profound psychological effects, effects that can be disruptive and painful for the helper and can persist for months or years after work with traumatized persons” (McCann & Pearlman, 1990, p. 133). This includes changes to the helper’s worldview.

“a state of tension and preoccupation with the traumatized patients by re-experiencing the traumatic events, avoidance/numbing of reminders persistent arousal (e.g., anxiety) associated with the patient. It is a function of bearing witness to the suffering of others” (Figley, 2002, p. 1435).

the sense of reward, efficacy, and competence one feels in one’s role as a helping professional (Figley, 2002 as cited in Killian, 2008).

positive outcomes of experiencing trauma, either directly or indirectly.

“the transformations in the therapists’ inner experience resulting from empathetic engagement with the client’s trauma material” (Hernandez et al., 2007, p. 237).