4 Practice Competencies to Effectively Support Wellness for Social Workers and Clients in Northern Saskatchewan Communities

Wanda Seidlikoski Yurach; Carrie LaVallie; and Vivian R Ramsden

Social workers carry out trauma counselling services in northern communities because this kind of work requires someone with a generalist background who can practice independently (Coholic & Blackford, 2003; Graham et al., 2008). Delivering trauma supports in northern Canada, social workers most often use the title of mental health therapist or mental health provider (Assembly of First Nations, 2015; O’Neill et al., 2016). Northern communities have difficulty retaining mental health providers/social workers because outside of northern communities, very little is known about what is needed to support their well-being to carry out this work (Mental Health Commission of Canada, 2012). Kiawenniserathe Benedict (2015) contends that northern human service work including social work is extremely challenging and believes healthy/supportive workplaces are required to mitigate the range of demands. Therefore, social workers need access to evidence-informed practice competencies to protect their well-being in order to create psychologically safe work places to carry out northern trauma work effectively and sustainably and in turn improve services for and with northern clients (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). Although the main focus of this chapter is northern social work practice competencies, rural Canadian social workers may have similar experiences, such as limited access to well-being supports and isolation from professional colleagues (Goodman, 2012). The information covered in this chapter includes: a review of the complexities of working in northern communities; social work practice barriers/challenges for social workers in northern practice; practice competencies that support/protect the well-being of northern clients and social workers; an overview of micro, mezzo, macro skills; as well as discussion questions, activities, and references. Overall, this chapter addresses the following question: What are the practice competencies and supports social workers require to protect their well-being in order to navigate central complexities of northern practice and provide a relational participatory approach to service delivery in northern communities? This question is answered by explaining the unique complexities of northern social work trauma practice, adapting social work practice competencies to incorporate the well-being of workers, and exploring ethical and sustainable undertakings at the micro, mezzo, and macro level.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will have had the opportunity to:

- Be aware of the complexity of Canadian northern and rural social work practice in order to create a safe work environment and mitigate ethical dilemmas.

- Learn how to employ a relational participatory practice approach through critical reflection and enhanced well-being in order to help others.

- Learn how to apply ethical and sustainable social work practice competencies at the micro, mezzo, and macro levels when working with communities in northern Canada.

Complexities of Working in Northern Communities

New social workers in northern communities have often reported experiencing culture shock and difficulty fitting in (Cruikshank, 1990; Zapf, 1993), and Indigenous clients reported feeling guarded about non-Indigenous social workers/counsellors/therapists in their communities (Morrissette & Naden, 1998). Northern social workers have often faced trust issues with their clients whether from inside or outside the community. Therefore, workers need to use a generalist trauma-informed approach to build trust with clients to effectively carry out services while at the same time protecting their own health and well-being (O’Neill et al., 2016; Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). As well, northern communities are closely connected and as a result, professionals such as social workers often encounter situations that challenge their Codes of Ethics, such as dual relationships and lack of confidentiality (Bishop & Schmidt, 2011; Galambos et al., 2006; O’Neill et al., 2016). Social workers provide trauma counselling within Indigenous communities that have experienced elevated rates of emotional pain along with reduced access to needed services (Hackett et al., 2016; Lavoie & Gervais, 2012). The lack of resources and increased demand for services demonstrate the complexity of working in northern communities.

Formal mental health professional service providers, which included social workers, were studied in a multi-phase project in the following Canadian locations: Yukon, British Columbia, Alberta, Northwest Territories and Nunavut (O’Neill et al., 2016); the purpose of the study was to identify and hear experiences of providing trauma support in isolated locations. Although trauma providers reported increased levels of compassion as a result of working in northern communities, they also talked about feeling emotionally empty due to the long hours they were required to work (O’Neill, 2010). As well, providers have reported quitting their jobs or leaving trauma care altogether when they were unable to balance the demands of the work (Harrison & Westwood, 2009; Kanno, 2010), or to manage the emotional distress they were experiencing (Bride, 2007).

Despite their commitment to their clients and communities, northern social workers described having encountered the following barriers: high complex-trauma caseloads, limited self-care resources, insecure program funding, and high rates of staff turnover (O’Neill et al., 2013). Humility and confidence are required to maneuver the barriers within isolated northern trauma work, which can be especially difficult for a new social worker (O’Neill et al., 2016). The complexities, isolation, and high trauma case loads in northern social work can increase one’s risk of secondary trauma further discussed in the next section.

Isolation and Secondary Trauma

Isolation is a significant obstacle for northern trauma workers and limits their access to colleagues and clinical supervision (Coholic & Blackford, 2003; O’Neill et al., 2016). Also, the demanding nature of remote northern trauma work is exacerbated by the isolation and may increase providers’ vulnerability to secondary trauma (O’Neill, 2010). Secondary trauma can include mental health effects such as inability to trust, and loss of freedom and safety (cognitive shifts); upsetting or lack of feelings, increased startle response, and the inability to carry out normal activities (psychological distress) (Collins & Long, 2003); and feeling disconnected from friends, family, and one’s clients (Elwood et al., 2011).

Distress or secondary trauma due to trauma counselling is described in the literature using several terms including secondary traumatic stress, burnout, and compassion fatigue (Collins & Long, 2003; Elwood et al., 2011; Hensel et al., 2015). Although this variation in terminology creates some challenges in comparing results, there appears to be agreement in the literature that secondary traumatic stress occurs because of wanting to alleviate the emotional pain of a client (Figley, 1995). Secondary trauma symptoms can develop rapidly and intensify into secondary traumatic stress disorder – much like Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Figley, 2002). Furthermore, PTSD diagnostic criteria now includes the repeated indirect exposure to unpleasant details of events that are traumatic (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Consequently, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (2013) recommended that “labour laws, occupational health and safety, employment standards, workers’ compensation, the contract of employment, tort law, and human rights decisions are all pointing to the fact that employers must provide a psychologically safe workplace” (p. 53).

Listening to understand the emotional pain of another requires empathy, but it also often results in impact on the therapist (Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995). Trauma counselling involves listening to clients’ horrific stories and can negatively impact a worker (Hensel et al., 2015; O’Neill, 2010). Workers primarily dealing with traumatized clients are reportedly more likely to experience secondary trauma (Bride, 2007; Pearlman & Mac Ian, 1995). Bride (2007) reported that more than 70% of social workers providing trauma support in her study experienced at least one symptom of secondary traumatic stress, and 15.2% met the criteria for PTSD. Many northern human service providers also identified experiencing attributes consistent with secondary trauma such as loss of compassion, lack of sleep/exhaustion, and hypervigilance (O’Neill, 2010). As a result, northern providers experiencing high levels of distress can often struggle to meet the needs of their clients as well as their own (O’Neill, 2010).

Significant secondary traumatic stress risk factors include: a worker’s age, years of experience, personal trauma, trauma caseload, and access to personal as well as workplace supports (Hensel et al., 2015). Being new to the job was found to be the strongest work-related predictor of secondary trauma (Devilly et al., 2009). In addition, secondary trauma contributing factors specifically related to practicing in northern Canada were reported to include: worker’s trauma history; listening to trauma narratives; observing a client’s physical trauma wounds, and insufficient capacity to deal with stress (Bishop & Schmidt, 2011).

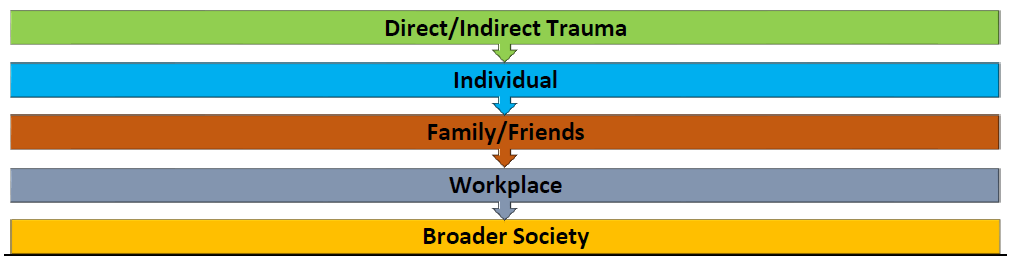

Trauma workers can also sometimes struggle to separate themselves from their clients’ stories because of their own unhealed trauma (Bishop & Schmidt, 2011; Ludick & Figley, 2016). Workers with unresolved trauma may generate protective emotional barriers that can undermine the therapeutic relationship (Collins & Long, 2003). Ludick (2013) recommended that human service providers detach from their clients’ trauma stories, because those who can do so are the least negatively impacted by their work. Also, social workers who interview for solutions and focus on their client’s resilience are better able to reduce their own risk of secondary trauma, even when they have trauma histories similar to those of their clients (Morrisette & Nadan, 1998). Social workers must often be the ones who set measures in place to support their well-being (Bercier & Maynard, 2015). For example, to reduce the likelihood of secondary trauma, a social worker must clearly define and protect their own empathic boundaries to maintain their well-being and capacity to work with their clients (Ludick & Figley, 2016). As well, workers experiencing secondary trauma should discontinue providing services as this is not healthy for themselves or their clients (Bride, 2007; Harrison & Westwood, 2009). Social workers also need to understand that the negative emotional and psychological implications of trauma counselling can also extend to their own family and other people close to them (Pearlman & Saakvitne, 1995; Westman & Bakker, 2008). For example, social workers in northern Saskatchewan report sometimes being unable to connect emotionally to their family (children/partner) and friends (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). Figure 1 demonstrates the linkages between direct and indirect trauma and the trickle-down effect from social worker to the broader society.

Figure 1

The Broad Reaching Implications of Direct and Indirect Trauma

The job demands of northern and rural social work, including time away from home, affects both the worker and their family. Social workers also identified that isolation and secondary trauma negatively affected their cognitive and psychological well-being. Northern practice creates unique challenges that require social workers to be aware of strategies and competencies to strengthen/support their own well-being, their families’, and their clients’. Well-being and safety-supports at the individual and organizational levels are vital for northern social workers to manage the potential impact of their work (Barrington & Shakespeare-Finch, 2014). These strategies will be discussed in the next section.

Supporting and Protecting the Well-being of Northern Providers

O’Neill et al. (2016) argued that the implications of indirect trauma exposure are especially of interest for human service providers working in remote locations in Canada. To protect the well-being of providers, including social workers in isolated northern communities, workers must effectively use local community services and supports; they must be open to adopting cultural and trauma-informed practice competencies (O’Neill et al., 2016). Goodwin et al. (2016) recommended that an interdisciplinary team approach should be a job expectation for mental health workers in northern Canada to better meet the needs of the community, and to offset the effects of isolation. For example, social workers need to actively seek out and establish relationships with a broad range of community supports such as Elders, nurses, teachers as well as parents and youth to develop a collaborative/collective toolkit of services that could be delivered. These community connections help to increase supports to clients and in turn reduce the isolation from one’s peers/colleagues experienced by northern social workers.

In 2013, four Saskatchewan First Nations Tribal Councils piloted a project to develop/train community-based mental wellness teams and support linkages between local trauma-informed formal and informal resources (Hill et al., 2016). Social workers in northern communities can also link into these interdisciplinary teams for increased support. Another method of supporting a team approach would be to connect northern providers/social workers through a “community of practice” to provide a platform for workers to engage and discuss innovative methods of practice (Wenger & Snyder, 2000) collectively and supportively. The term “community of practice” was defined by Wenger and Wenger (2015) as “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (p. 1). A “community of practice” requires: a common purpose or concern; relationships that support participants capacity to learn and offer learning to others; collaborative building of capacity by sharing solutions to recurring issues; and a forum to discuss experiences and methods of practice (Wenger & Wenger, 2015).

Lawson et al. (2009) argues that northern social workers require support strategies to reduce the isolation and work demands to prevent burnout and job attrition. These support strategies include provision of resources to reduce isolation; training to expand one’s knowledge and skills; and supervision to develop effective practice competencies and supports (Lawson et al., 2009). In addition, northern Canadian providers have identified a need for formal clinical supervision, teamwork, routine debriefings, and access to informal supports such as friends and/or family to provide services over the long term (Bishop & Schmidt, 2011; O’Neill et al., 2016). McKee and Delaney (2009) propose that northern social workers partner with communities to meet their identified needs. Authentic and sustainable partnerships must be based on “context-sensitive knowledge for practice” (McKee & Delaney, 2009, p. 330). Through a participatory narrative inquiry study lens, the next section introduces practice competencies specific to protecting the well-being of northern-based trauma support social workers.

Key Practice Competencies for Northern Social Workers

A brief overview of a participatory narrative inquiry of trauma-support social workers will be discussed to understand their experiences in northern Saskatchewan. It is important for social work standards of practice specific to northern and rural practice to be research-informed. Through the stories, we can gain valuable insight specific to providing trauma-informed services that also supports the well-being of social workers. Ten trauma-support social workers with experience working in northern Saskatchewan’s Indigenous communities were interviewed regarding their lived experiences. They made the following recommendations to improve providers’ sense of belonging and safety and to ease the overall impact of job demands. These included: adopting a team approach; building strong working relationships with supervisors/managers; and expanding overall access to formal supports including a “community of practice” (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). Social workers involved in the study also provided recommendations about practice competencies including: collaborative/relational participatory skills; a continual process of critical self-reflection of one’s knowledge/values; practice through a reconciliatory trauma-informed lens, employing cultural humility; and improving northern workplace well-being and safety supports (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021).

The standards of practice developed by the Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers (SASW, 2020) in 2020 set out the competencies which registered social workers in the province must adhere to for the benefit of their clients; these competencies include ethics, advocacy, culture-based interventions, collaboration, and new insightful methods of engagement/intervention. Although standard practice competencies provide a basic and consistent level of expectations, they might limit social workers to more mainstream ways of approaching their practice. Therefore, we propose that northern social workers strive to develop the following northern practice competencies:

- Encouraging social workers to connect with other social workers to build a strength-based collaborative “community of practice”

- Understanding the context of northern communities

- Engaging in critical self-reflection and cultural humility

- Engaging in a relational participatory reconciliatory approach to meet the service needs of northern communities while recognizing ethical dilemmas such as dual roles.

- Utilizing trauma-informed practices

- Supporting workplace safety and wellness

Building authentic supportive relationships within northern communities and connecting with outside resources/supports, clinical supervision, and standards of practice are instrumental to the well-being/resiliency of northern social workers to sustain service provision. In addition, understanding Indigenous peoples’ trauma history is needed in order to support and protect well-being.

Importance of Northern Social Workers Understanding Indigenous Peoples’ Trauma

Social workers who want to work in northern Indigenous communities need to understand how intergenerational trauma and the negative health implications associated with such trauma have developed because of colonization (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada [TRC], 2015). A recommendation from the Assembly of First Nations (2015) was to establish a process to support “existing and future providers from Western-trained programs in developing cultural safety, trauma-informed practice approaches, harm reduction skills, as well as a deep historical understanding of First Nations health, ongoing colonization, intergenerational trauma, and its effects” (p. 27). In addition, one of the TRC’s Calls to Action (2015) is provision of “cultural competency training to all healthcare professionals” (p. 2). Allen and Smylie (2015) strongly suggested that mental health providers should be trained in “cultural competence, cultural safety… and trauma-informed care” (p. 36). As discussed earlier in this chapter, the Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers (SASW, 2020) has developed practice competencies that include cultural competence. Therefore, all social workers, but more importantly those that work in northern Canada, must take steps to practice competently. Social workers must learn their own family histories, cultures, and ways of thinking, along with those of their clients, so they can integrate this information into their practice (SASW, 2020).

When providing social work support and counselling support to Indigenous peoples, one must prioritize learning about colonization, along with the current systemic inequalities and racism that create ongoing trauma (Stewart, 2009). It is imperative for providers to be aware of the history of Indigenous peoples in order to understand the circumstances that have created the trauma within the communities in which they work (Stewart, 2009). Social workers need to understand that Indigenous peoples in Canada have been subjected to a purposeful strategic process of assimilation through colonization (Thompson et al., 2010). For instance, the forced removal of Indigenous children to attend residential schools undermined their culture and family bonds (Ross, 2014; TRC, 2012), and created mass intergenerational and interpersonal trauma that continues today (Thompson et al., 2010).

To strengthen the self-determination of Indigenous peoples and communities, social workers in northern communities must engage in a continuing process of self-reflection and fully appreciate the direct link between the history of Indigenous peoples and the current issues faced by northern communities. Allan and Smylie (2015) argued that understanding and reflecting on the impact of racism helps generate a process of decolonizing the delivery of services for and with Indigenous peoples. Social workers engaging in northern practice must actively understand, believe in, and fully participate in reconciliation efforts. As an active participant in reconciliation, one must engage with a curious mindset and self-reflection that supports an openness to learning. An overview of this process will be provided in the next section.

Learning Through Curiosity and Critical Self-Reflection

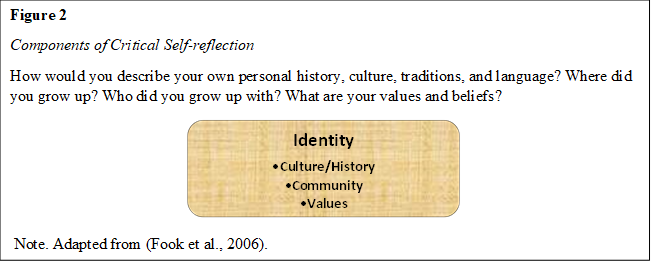

Northern Canada is more than just a geographical region for Indigenous peoples; it is home, has a sense of purpose, and is sacred (Schmidt, 2009). Professional supports for those working as social workers in northern Canada must have a broad understanding of the “traditional worldview of Aboriginal People” (McCormick, 2009, p. 338). Culturally-uninformed service providers might unknowingly undermine their Indigenous clients’ beliefs, thereby generating additional stress (McCormick, 2009). Health and social service providers need to engage in a process of self-reflection regarding their personal values and cultural principles when working with Indigenous peoples (Moss et al., 2012) as shown in Figure 2.

McKee and Delaney (2009) suggested that northern social workers need to understand the complexities of each community and suspend or change their own beliefs and ideas in order to provide appropriate anti-oppressive services. McKee et al. (2009) provides a list of critical self-reflection questions for social workers in these communities:

- What knowledge am I attempting to bring to this situation? Where did I learn this? How is this learning getting in my way?

- Why is this way of making sense of this situation so automatic to me? Why is this pet theory so dear to me? Why am I having trouble giving it up so that I can approach this situation differently?

- Whose voice is being heard in this knowledge I take to be so real? Is it my own, based upon my own authentic experience, or someone else’s? What aspects of my own experience are being misrepresented or silenced by this knowledge I take so much for granted? (p. 202). This self-reflection process is further demonstrated in Figure 3, and you are encouraged to engage in your own process of self-reflection by using these questions and process as a guide.

Figure 3

What is your reality?

How would you answer the above noted questions? What might get in the way of you being able to answer these questions? How has your reality been formed?

Note. Adapted from (McKee et al., 2009).

Stories can be an effective way to set the stage for self-reflection and curiosity. For example, an Elder sat with two colleagues one morning to enjoy some conversation over a cup of coffee. The conversation began with pleasantries and then turned to the topic of grief. At that point, one of the colleagues expressed that they did not want to engage in such a serious discussion. This was supposed to be a pleasant morning of coffee and conversation. The Elder picked up on this tension and chose to tell a story in order to intervene. He began his story by asking “Did you know I’m writing a book”? To which his colleagues replied, “No.” He said “Yes, it’s called looking at the world through a pin hole in a blanket. It’s about a boy who can only see the world through this pinhole, but as he is more curious to see the world, that pinhole expands and he is able to see so much more.” The two colleagues looked at each other and then at the Elder. With a smile, they realized that no more needed to be said; they ate their breakfast, drank their coffee, and enjoyed each other’s conversation. The story shared by the Elder created space for everyone at the table because each of the colleagues had a choice about its message. One such message might be that a person’s defensiveness can keep them from seeing all that there is to see. When you get frustrated or defensive, remember this story and be aware that sometimes we all need to be silent and listen. As well, we may not know what there is to learn in a particular moment, but through a process of reflection we will learn something from it. This story resonates with social workers as we focus much if not all our attention on the needs of others. This is how we view the world through the “pinhole in our blankets.” Although focusing our attention on the needs of clients is an important aspect of trauma-informed practice, we must expand our view to include the needs of social workers as well.

Workplace Safety and Wellness – Trauma-Informed Practices and Supports

To better support clients in healing their trauma, counsellors, and social workers themselves require safeguards in their workplaces to shield them from secondary traumatic stress (Kanno, 2010). In order to learn how to effectively work in northern communities one must actually work in a northern community (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). There is no textbook that can quite prepare someone for the work that they will do in northern communities. One must hit the ground running and do whatever is placed in front of you (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). Social workers must understand the implications of working with trauma stories. They must also understand that they are all part of the colonial trauma history as well as the colonial practices that continue in Canadian society today.

Human-service providers require confidence, competence, and compassion, with the emotional capacity to cope with the demands of trauma work (Ludick & Figley, 2016); those who feel more confident in their skills are less likely to experience burnout or compassion fatigue (Ortlepp & Friedman, 2002). Social workers are more likely to enjoy their job (compassion satisfaction) and be protected from fatigue and burnout when they assist others, have positive co-worker relationships, and promote wellness both at work and more broadly (Stamm, 2010). Further recommendations by Ludick and Figley (2016) include the importance of screening potential employees to determine their suitability for trauma work and requiring employers to develop workplace wellness supports to protect workers from secondary traumatic stress.

Social workers truly informed about traumatic learning are required to commit to conscious participation in creating greater safety for their clients and for themselves. Zingaro (2016) argues the focal point of social work is to develop relationships that incorporate and contextualize trauma while “providing support, information and understanding and as much experience of safety as we can manage” (p.35). Safety includes self-care, which is a significant factor in the well-being of providers including social workers (Wieman, 2009), supporting a worker’s capacity to adapt to challenging situations (Salston & Figley, 2003). Nelson-McEvers (1995) defined self-care as learned patterns of action and strategies to preserve or protect overall health. Kaushik (2017) argued that social workers’ self-care needs must include engaging in a process of maintaining or repairing their own emotional well-being and explains the following:

Pain, despair, and suffering equally affect us as they do to the clients we serve. … How can, we, the service providers, claim to help our clients deal with their suffering if we cannot ameliorate our pain? Just as a drowning person cannot save other drowning people, we the social workers cannot heal others unless we heal ourselves. (p. 27)

Providers working in remote northern communities in Canada have also identified the desire to incorporate trauma-informed practices into their work as a strategy to support and protect their emotional and psychological well-being (O’Neill et al., 2016). Trauma-informed practice competencies involve understanding the impact of trauma on clients and helpers, and implementing the most appropriate/effective method of treatment (SAMHSA, 2011). Thus, it is important to spend time in the community with community members building relationships and learning (Canadian Institutes of Health Research et al., 2018).

Northern communities have a keen sense of connection bound by geographical location, landscape, and kinship, as well as cultural practices. Outsider mental health providers learn about the community they are working in by talking with Elders and residents (O’Neill et al., 2016). Social workers wanting to participate in northern community work must understand that they will face many challenges, but they will also have the honor and opportunity to understand and immerse themselves within an authentic community participatory experience (Schmidt, 2009). Being competent in one’s skills to work in northern practice includes a relational participatory approach. By seeming to understand the trauma of northern clients and by doing so through a trauma-informed lens, social workers are not only able to better work with and for clients in northern communities, but are also better able to support/protect the needs of themselves and other social workers (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021).

Relational Participatory Approach to Social Work in Northern Practice

Folgheraiter and Raineri (2012) suggested that “in genuine relational social work, there is not one party who seeks to provide well-being to another; everybody pursues the well-being of everyone else together” (p. 480). As well, “in any helping relationship, the help is only produced when the worker accepts help from the interested parties as if they themselves were workers” (Folgheraiter & Raineri, 2012, p. 484). To work competently within a relational participatory approach, social workers must also acknowledge everyone’s humanity including their own (Folgheraiter & Raineri, 2012); they must view all relationships as essential, including those with clients, co-workers, and supervisors (Ruch, 2009). For social workers to effectively work within northern communities, they must genuinely and authentically engage in developing strong, trusting, and mutually-respectful relationships with their clients and the community.

Winter (2019) maintains that relational practice is based on “being real, committed, responsive in thoughtful ways; and also, being able to regulate one’s own emotional responses and react responsibly to the emotions of others” (p. 13). For social workers to practice relationally with clients, they must understand that transformation and growth occurs because of the relationship; healing can occur even though the relationship is not equal; and positive results require working together through their connected worlds “interpersonal, intrapersonal and structural” (Winter, 2019, p. 13). Howe (1998) advises a relational participatory approach requires social workers to acknowledge their personal traits or nuances and how this might impact the client and the worker. Moreover, a relational participatory approach requires competent oversight, guidance, and facilitation.

Social workers should anticipate that many of the relationships they will engage in professionally within northern communities will have ethical complexities such as dual roles and boundary issues. To assist the social worker in navigating ethical dilemmas, they can be encouraged to refer to documents provided by social work regulatory bodies, as well as colleagues, for guidance. For example, the Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers (2020) outlines the following standards of practice required to protect the client when dual relationships are likely to occur:

- Consult with another social worker regarding the dual/multiple role relationship and subsequent provision of professional services to the client and include the contents of the consultation in the client’s record.

- In all cases when a dual/multiple role relationship exists the social worker is solely responsible for ensuring that appropriate professional boundaries are maintained, and that the client-social worker relationship is protected.

- Where a social worker’s personal circumstances result in frequent contact with clients outside the practice setting, a social worker shall take reasonable measures to discuss with all clients how contacts outside the professional context will be managed to protect the client’s interests (p. 23).

Building relationships, although key in effective northern and rural practice requires a careful balance between developing specific skills beyond the scope of empathy to include sincerely caring for another while putting in safeguards to protect one’s client. The relationships need to be reciprocal and consider not only the well-being of the client but that of the social worker. In the next section, we will further examine why northern community relationships need to be meaningful with suggestions for how this might take place.

Building Meaningful Client-Worker Relationships – Care and Love

Delivering mental health services in northern communities requires social workers to build genuine/authentic participatory relationships with clients and communities so that they can work collaboratively and competently. McCormick (2009) recommended that provider/client relationships must be collaborative not only to provide safe services to clients, but also to protect the safety and well-being of providers. Building relationships, particularly for outsiders in Indigenous communities, takes time due to the historical implications of colonization. It is important to remember that “social work discourses have never given permission for us to love the people we work with, although words such as care, empathy and compassion have long been used” (Massing, 2017, p. 174). Social workers working in northern Saskatchewan Indigenous communities have described “loving” the people and communities they work in and how heartbreaking it is when they leave (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021).

Rollins (2020) argues every social work relationship is purposeful and unique requiring “a sustained focus on intervention, purpose and goals. At the same time, social workers are focused on developing, retaining, retrieving, and repairing these relationships that in turn, can also enhance the client’s own relationship capacity” (p. 399). One of the most important aspects of working in northern Indigenous communities is to patiently hold the necessary space for trusting relationships to develop. For example, northern Saskatchewan social work mental health providers indicated that longer term work within Indigenous communities was more effective than short term crisis-work, because trusting relationships take time to develop (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). Building relationships within northern Indigenous communities helps to improve the social workers’ access to local supports, which in turn helps to buffer the impact of isolation.

Building relationships requires being respectfully curious and learning about the community. It is important to find out what the community wants/needs and then explore and develop solutions together (Kurtz, 2014). Each relationship will have its own unique complexities and take time, often years, to develop (Mayan & Daum, 2016). Each relationship within northern communities, although timely, is worth every moment of effort when engagement is fully collaborative. It is also important that social workers understand that they are likely an outsider (not from the community), and therefore they should ask permission or wait to be invited to share their opinion. A person must understand that the invitation for them to provide an opinion could take years. Factors such as colonization, being a government agency representative, being an outsider, having western values, and/or being non-Indigenous influence the length of time it can take to build a collaborative, respectful relationship within a northern community. Taking time to develop relationships is key to building trust within northern and rural communities and in turn, helps to reduce the isolation social workers experience especially as a new social worker. Focusing on the strengths of a community and taking steps to work with and for a community at all practice levels supports healing efforts driven by clients and their communities. An expanded discussion of the micro, mezzo and macro levels of practice and its connection to safety will follow.

Micro, Mezzo, Macro Practice Competencies

Social workers, providing services in northern communities, have reported needing to feel safe to effectively carry out their work at a micro, mezzo, and macro level (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). To feel safe, it is important for social workers to rely on foundational social-work skills that include building authentic relationships, cultural competence, empowerment, critical thinking, evaluating the effectiveness of approaches, and knowing how to work with at-risk individuals and communities (Austin et al., 2016). Social workers can also feel safer in their work by being able to access supports such as clinical supervision, scheduled debriefings, and safe accommodations; they also need to be part of a work team to carry out collaborative and interdisciplinary northern services (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021).

Each level of northern social work practice whether micro, mezzo, or macro requires specific skills. For example, a social worker’s focus at a micro level is on interpersonal and relational skills whereas at a mezzo level, they must focus on their ability to build broader relationships with agencies in communities that may have competing goals. They try also not to forget the overarching influences of the structural, political, financial, and ideological powers that social workers want and hope to change and adjust to meet the needs of all individuals. We will begin by discussing the micro level skills needed to work in rural and northern communities.

Micro

Social workers must pay particular attention to individual, interpersonal, and group skills which include engaging in self-reflection at a micro skill level to appropriately deal with their own stress as well as their clients’ (Austin et al., 2016). In addition, at an interpersonal skill level, social workers must complete assessments, lead teams, and “manage power and privilege to effectively maintain relationships with clients and colleagues” (Austin et al., 2016, p. 273). For example, when working in northern communities, a social worker who does not know the local language can still support their client to tell their story in their first language. The provider does not need to understand the client’s story. Finally, group skills are needed to create, empower, and maintain teams and support a process for those teams to follow through with their recommendations for change (Austin et al., 2016).

It is also important for social workers not to go into northern communities focused on healing what they perceive as broken, but instead they should focus on the assets and vitality of the people and community (Barter, 2009). Taking a more strength-based and collaborative approach to practice also creates an opportunity for the community to work together to utilize their own ways of doing and healing (Barter, 2009). The following section will explain how social workers can work with the organizations and agencies within communities to support well-being and healing.

Mezzo

Social workers do many things at a mezzo level in a northern community. For example, workers should take time to visit each northern community agency they work with. During these visits they introduce themselves, explain their role, and spend time getting to know the individuals that work in the different agencies. They do not need to wait for people to come to them; instead, it is important that they make the effort to be engaged with people. Making time to visit those agencies in other communities in the region on a regular basis will build and strengthen relationships and networks. The connections and constructing networks that are instrumental to building multidisciplinary interagency teams have been identified by northern social workers as crucial to their work and well-being. Networking is key not only with agencies within the community but also with those outside the community. External resources include specialized mental health services such as psychiatry, in-patient treatment centres for addictions, and safe shelters. More importantly. the allocation, availability and accessibility of resources are also greatly influenced at a macro level by a variety of political and economic structures. Therefore, the social worker’s felt-sense regarding macro level challenges within northern/rural systems will be discussed next.

Macro

Although pursuing social justice is a core value of social work (Canadian Association of Social Workers, 2005) social workers working in northern Saskatchewan have reported feeling powerless to effect change at broader levels such as “structural inequalities and systemic racism” (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021, p. 131). Social workers providing services in northern Saskatchewan describe their jobs as very demanding and often said that “focusing on systemic issues were not only overwhelming but would take away from what they believed they could do” (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021, p. 131). Northern social workers acknowledge the importance of systemic changes; however, they often struggle to find the time and energy to focus on these issues. Social workers have identified needing to make the conscious choice to carry out their role at a micro level due to the time demands of northern work. Knowing other social workers have had this common experience can help to affirm and normalize feeling powerless at times in these situations.

Conclusion

Working in northern and rural communities requires knowledge regarding how to address the unique complexities of each community, as well as adopting and adapting effective practice strategies. This includes utilizing a relational participatory approach to better support the needs of clients and foster the well-being of social workers. By understanding the significance of relationships within rural/northern communities, social workers are better able to maneuver the ethical challenges such as dual roles, and more readily adopt a team approach to reduce isolation from colleagues. Overall, northern social workers have identified safety as key to trauma work and support for their well-being, which in turn helps to reduce their risk of secondary trauma. As well, knowing the competing demands of providing services in northern and rural settings can undermine one’s capacity to effect change at a systemic level. These practice strategies to assist in meeting the needs of clients, communities and social workers include:

- Social workers seeking to provide effective services and supports must incorporate a relational participatory approach by reflecting on their own trauma history, leading with humility, and supporting clients in telling their story in their own language (Winter, 2019).

- Social work education programs can support and expand training specific to “the development of northern practice skills by adopting a northern perspective based on collaborative partnerships guided by high degrees of context sensitivity and context awareness” (Lawson et al., 2009, p. 303).

- Evidence-informed practice competencies are needed in order to develop ethical, safe, and supportive work places for sustainable social work, including trauma work, in northern Canadian communities. Implementing a “community of practice” can help new and seasoned northern social workers in easing the effects of isolation and secondary trauma (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021).

Activities and Assignments

- Write down a list of resources for both clients and social workers that you would readily have available in a more urban setting in Canada. Review your list individually or as a group and decide which resources and supports might be inaccessible in a more rural or northern location in Canada. Discuss what would be required to have easier access to these resources.

- Whom might northern social workers develop collaborative linkages with to create workplace well-being supports and safety for all northern social workers?

Additional Resources

- Makokis, P., & Greenwood, M. (2017). What’s new is really old: Trauma informed practices through understanding historic trauma.

- Rzeszutek, M., Partyka, M., & Gołąb, A. (2015). Temperament traits, social support, and secondary traumatic stress disorder symptoms in a sample of trauma therapists. Psychotherapy Research Practice & Practice, 46(4), 213-20.

References

Allan, B., & Smylie, J. (2015). First peoples, second class treatment. The role of racism in the health and well-being of Indigenous peoples in Canada. The Wellesley Institute.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed).

Assembly of First Nations (2015). First Nations mental wellness and the non-insured benefits (NIHB) short term crisis intervention mental health counselling (STCIMHC) benefit. https://www.afn.ca/uploads/files/2015_usb_documents/afn_document_review_stcimhc_nov_2015.pdf

Austin, M., Anthony, El, Tolleson Knee, R., & Mathias, J. (2016). Revisiting the relationship between micro and macro social work practice. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 97(4), 170-277.

Barrington, A., & Shakespeare-Finch, J. (2014). Giving voice to service providers who work with survivors of torture and trauma. Qualitative Health Research, 24(12), 1686-1699.

Barter, K. (2009). Reclaiming community: Rethinking practices for the social work generalist in northern communities. In R. Delaney & K. Brownlee (Eds.), Northern and rural social work practice a Canadian perspective (pp. 209-221). Lakehead University.

Bercier, M. L., & Maynard, B. R. (2015). Interventions for secondary traumatic stress with mental health workers: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice, 25(1), 81–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731513517142

Bishop, S., & Schmidt, G. (2011). Vicarious traumatization and transition house workers in remote, northern British Columbia communities. Rural Society, 21(1), 65-73.

Bride, B. (2007). Prevalence of secondary traumatic stress among social workers. Social Work, 52(1), 63-70.

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). CASW code of ethics. https://www.casw-acts.ca/files/documents/casw_code_of_ethics.pdf

Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Natural Sciences and Engineering, Research Council of Canada, & Social Sciences and Humanities Research. (2018, December). Council, tri-council policy statement: Ethical conduct for research involving humans. Government of Canada. http://www.cihr-irsc.gc.ca/e/48413.html

Coholic, D., & Blackford, K. (2003). Exploring secondary trauma in sexual assault workers in northern Ontario locations – the challenges of working in the northern Ontario context. Canadian Social Work, 5(1), 43-58.

Collins, S., & Long, A. (2003). Working with the psychological effects of trauma: Consequences for mental health‐ care workers – a literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10, 417-424.

Crisis & Trauma Resource Institute (2021). A little book about trauma-informed work-places. Achieve Publishing.

Cruikshank, J. (1990). The outsider: An uneasy role in community development. Canadian Social Work Review / Revue Canadienne De Service Social, 7(2), 245-259.

Devilly, G. J., Wright, R., & Varker, T. (2009). Vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress or simply burnout? Effect of trauma therapy on mental health professionals. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(4), 373.

Elwood, L., Mott, J., Lohr, J., & Galovski, T. (2011). Secondary trauma symptoms in clinicians: A critical review of the construct, specificity, and implications for trauma-focused treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 25-36.

Figley, C. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In C. Figley, (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 1-20). Routledge.

Figley, C. R. (2002). Compassion fatigue: Psychotherapists’ chronic lack of self care. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(11), 1433-1441.

Folgheraiter, F. & Raineri, M. (2012). A critical analysis of the work definition according to the relational paradigm. International Social Work, 55(4), 473-487.

Fook, J., White, S., & Gardner, F. (2006). Critical reflections: A review of contemporary literature and understandings. In S. White, J. Fook, & F. Gardner (Eds.), Critical reflection in health care (pp. 3-20). Open University Press.

Galambos, C., Watt, J., Anderson, K., & Danis, F. (2006). Ethics forum: Rural social work practice: Maintaining confidentiality in the face of dual relationships. The Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics.

Goodman, P. (2012). Rural Health Training Institute. In J. Kulig & A. Williams (Eds.), Health in rural Canada (pp. 101-117). UBC Press.

Goodwin, S., MacNaughton-Doucet, L., & Allan, J. (2016). Call to action: Interprofessional mental health collaborative practice in rural and northern Canada. Canadian Psychology, 57(3), 181-187.

Graham, J., Brownlee, K., Shier, M., & Doucette, E. (2008). Localization of social work knowledge through practitioner adaptations in northern Ontario and the Northwest Territories, Canada. Arctic. 61(4), 399-406.

Hackett, C., Feeny, D., & Tompa, E. (2016). Canada’s residential school system: measuring the intergenerational impact of familial attendance on health and mental health outcomes. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(11), 1096-1105.

Harrison, R., & Westwood, M. (2009). Preventing vicarious traumatization of mental health therapists: identifying protective practices. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(2), 203-219.

Hensel, J., Ruiz, C., Finney, C., & Dewa C. (2015). Meta‐analysis of risk factors for secondary traumatic stress in therapeutic work with trauma victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 83-91.

Hill, M., Bruyere, T., & Mushquash, C. (2016). It takes a whole community: An evaluation of Saskatchewan mental wellness teams. Centre for Rural and Northern Health Research. Lakehead University.

Howe, D. (1998) Relationship-based thinking and practice in social work. Journal of Social Work Practice, 12(1), 45-56.

Kanno, H. (2010). Supporting indirectly traumatized populations: The need to assess secondary traumatic stress for helping professionals in DSM-V. National Association of Social Workers.

Kaushik, A. (2017) Use of self in social work: Rhetoric or reality. Journal of Social Work Values and Ethics, 14(1), 21-29.

Kiawenniserathe Benedict, A. (2015). Dying to get away: Suicide among Fir Nations, Métis and Inuit Peoples. In K. Kandhai (Ed.), Inviting hope: An exposé on suicide among First Nations, Inuit nd Métis Peoples (pp. 1-24). Aboriginal Issues Press.

Kurtz, C. (2014). Working with stories in your community or organization: Participatory narrative inquiry. Kurtz-Fernhout Publishing.

Lavoie, J., & Gervais, L. (2012). Access to primary health care in rural and remote Aboriginal communities: progress, challenges and policy directions. In J. Kulig & A. Williams (Eds.), Health in rural Canada (pp. 390-408). UBC Press.

Lawson, J., Arges, S., & Delaney, R. (2009). Local workers in rural and northern agencies: Strategies for effective partnerships. In R. Delaney & K. Brownlee (Eds.), Northern and rural social work practice a Canadian perspective (pp. 284-311). Lakehead University.

Ludick, M. (2013). Analyses of experiences of vicarious traumatisation in short-term insurance claims workers [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of the Witwatersrand.

Ludick, M., & Figley, C. R. (2016). Toward a mechanism for secondary trauma induction and reduction: Reimagining a theory of secondary traumatic stress. Traumatology,

Mayan, M., & Daum, C. (2016). Worth the risk? muddled relationships in community-based participatory research. Qualitative Health Research, 26(1), 69-76.

Massing, D. (2017). Relational ethics the third space. In E. Spencer, D. Massing & J. Gough (Eds.), Social work ethics: Progressive, practical, and relational approaches. Oxford University Press.

McCormick, R. (2009). Aboriginal approaches to counselling. In L. Kirmayer & G. Valaskakis (Eds.), Healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal people in Canada (p. 337-354). UBC Press.

McKee, M., & Delaney, R. (2009). Contextual patterning and metaphors: Issues for northern practitioners. In R. Delaney & K. Brownlee (Eds.). Northern and rural social work practice a Canadian perspective (pp. 57-66). Lakehead University.

McKee, M., Delaney, R., & Brownlee, K. (2009). Reflective practice: The key to context-sensitive practice in northern communities. In R. Delaney & K. Brownlee (Eds.), Northern and rural social work practice a Canadian perspective (pp. 192-208).

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2012). Changing directions, changing lives: The mental health strategy for Canada. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.ca/sites/default/files/MHStrategy_StrategySummary_ENG_0_1.pdf

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2013). Psychological health and safety in the workplace: Prevention, promotion, and guidance to staged implementation. National Standards of Canada. https://www.csagroup.org/documents/codes-and-standards/publications/CAN_CSA-Z1003-13_BNQ_9700-803_2013_EN.pdf

Morrissette, P., & Naden, M. (1998). An interactional view of traumatic stress among First Nations counselors. Journal of Family Psychotherapy. 9(3), 43-60.

Moss, A., Racer, F., Jeffery, B., Hamilton, C., Burles, M., & Annis, R. (2012). Transcending boundaries: Collaborating to improve access to health services in northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In J. Kulig & A. Williams (Eds.) Health in rural Canada (pp. 159-177). UBC Press.

Nelson-McEvers, J. A. (1995). Measurement of self-care agency in a noninstitutionalized elderly population. [Masters Theses, Grand Valley State University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

O’Neill, L. (2010). Northern helping practitioners and the phenomenon of secondary trauma. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 44(1), 130-149.

O’Neill, L., George, S., & Sebok, S. (2013). Survey of northern informal and formal mental health practitioners. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 72(1).

O’Neill, L., Koehn, C., George, S., & Shepard, B. (2016). Mental health provision in northern Canada: practitioners’ views on negotiations and opportunities in remote practice. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 38(2), 123-143.

Ortlepp, K., & Friedman, M. (2002). Prevalence and correlates of secondary traumatic stress in workplace lay trauma counselors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 15(3), 213-222.

Pearlman, L., & Mac Ian, P. (1995). Vicarious traumatization: An empirical study of the effects of trauma work on trauma therapists. Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 26(6), 558-565.

Pearlman, L., & Saakvitne, K. (1995). Treating therapists with vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress disorder. In C. Figley (Ed), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (pp. 150-177). Routledge.

Ross, R. (2014). Indigenous healing: Exploring traditional paths. Penguin Canada Books Inc.

Rollins, W. (2020) social worker–client relationships: Social worker perspectives. Australian Social Work, 73(4), 395-407.

Ruch, G. (2009). Identifying ‘the critical’ in a relationship-based model of reflection. European Journal of Social Work, 12(3), 349-362.

Salston, M., & Figley, C. (2003). Secondary traumatic stress effects of working with survivors of criminal victimization. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(2), 167-174.

Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers (2020). Standards of practice for registered social workers in Saskatchewan. https://www.sasw.ca/document/5075/Approved%20Standards%20Document%20eff%20March%201%202020.pdf

Schmidt, G. (2009). What is northern social work. In R. Delaney & K. Brownlee (Eds.), Northern and rural social work practice a Canadian Perspective (pp. 1-17). Lakehead University.

Seidlikoski Yurach, W. (2021). The power of stories: The experiences and well-being of mental health providers working in northern Saskatchewan communities [Doctoral dissertation, University of Saskatchewan]. Harvest. https://harvest.usask.ca/handle/10388/13346

Stamm, B.H. (2010). The Concise ProQOL Manual (2nd ed.). Pocatello.

Stewart, S. (2009). Family counselling as decolonization: Exploring an Indigenous social-constructivist approach in clinical practice. First Peoples Child & Family Review, 4(1), 62-70.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2011). Trauma informed approach and trauma specific interventions.

Thompson, S., Kopperrud, C. & Mehl-Madrona, L. (2010). Healing intergenerational trauma among Aboriginal communities. In A. Kalayjian & D. Eugene (Eds.). Mass Trauma and emotional healing around the world: Rituals and practices for resilience and meaning-making. Vol 2. Human made disasters. ABC-CLIO.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action.

Wenger, E., & Snyder, W. (2000) Communities of practice: The organizational frontier. Harvard Business Review, 78, 39-45.

Wenger-Trayner, E., & Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015). Communities of practice a brief introduction. https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/

Westman, M., & Bakker, A. (2008). Crossover of burnout among health care professionals. In J. Halbesleben (Ed.) Handbook of Stress and Burnout in Health Care (pp.111-125) Nova Science Publishers, Inc.

Wieman, C. (2009). Six Nations mental health services: A model of care for Aboriginal communities. In L. Kirmayer & G. Valaskakis (Eds.), Healing traditions: The mental health of Aboriginal people in Canada (pp. 401-418). UBC Press.

Winter, K. (2019). Relational social work. In M. Payne, & E. Reith Hall (Eds.), Routledge handbook of social work theory (pp. 1-10). Routledge.

Zapf, M. (1993). Remote practice and culture shock: Social workers moving to isolated northern regions. Social Work, 38(6), 694-704.

Zingaro, L. (2016). Traumatic learning. In N. Poole and L. Greaves (Eds.) Becoming trauma informed (pp. 29-36). Centre of Addiction and Mental Health.

Defined by Wenger and Wenger (2015) as “groups of people who share a concern or a passion for something they do and learn how to do it better as they interact regularly” (p. 1). A “community of practice” requires: a common purpose or concern; relationships that support participants capacity to learn and offer learning to others; collaborative building of capacity by sharing solutions to recurring issues; and a forum to discuss experiences and methods of practice (Wenger & Wenger, 2015).

By seeming to understand the trauma of northern clients and by doing so through a trauma-informed lens, social workers are not only able to better work with and for clients in northern communities, but are also better able to support/protect the needs of themselves and other social workers (Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021).