3 “It’s All About Context” – Knowing, Not Knowing and Everything In-between

Colleen McMillan; Natalie Compagna; and Hilton King

This chapter focuses on unlearning, learning, and understanding why context is paramount before practicing in northern and rural Indigenous Canadian communities. Context is explored and written in this chapter from the worldview narratives of a First Nation social worker, followed by a euro-western educated settler and academic, and lastly a recently graduated social worker living and working in a rural and northern community. These three first-person narratives explore context through historical associations with land, ethics and values, knowledge creation and why reflective and reflexive work is needed for a social worker to practice in northern and rural communities. The practice tensions embedded in these issues between the First Nation and euro-western worldviews are shared through case scenarios that highlight the work needed to ensure the social worker helps rather than harms. We conclude the chapter by offering an “epistemological Wampum Belt” as a transformative way for the two worldviews to move forward, contextually mindful of the uniqueness of rural and northern social work.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will have had the opportunity to:

- Appreciate the importance of context as a critical prerequisite for social work practice in rural and northern communities

- Question learned knowledge: identify spaces in one’s learning where harm can be unintentionally reproduced

- Deeply understand oneself and social location regarding western and Indigenous knowledge and how the two intersect in social work practice

- Learn and unlearn, and in the process, come to a place of cultural, contextual, and epistemological humility

“Context starts in the history’’: Land Acknowledgements as Relationship

This chapter is collaboratively written from three distinct worldviews: the first narrative is written by an Indigenous person who is a social worker, the second narrative by a euro-western educated academic and social worker, and the final by a recent Master of Social Work graduate working and living in a rural and northern community. We intentionally chose to write in this way to highlight the differences between worldviews and how disconnection among kinds of knowledges can occur and be transferred to a social work practice. We also wrote this way to show that collaboration between different worldviews can be achieved, when guided by core social work values such as respect, diversity, cultural appreciation, and dignity. Lastly, we believe writing this chapter in the more traditional or western way, as in using one “voice,” is disingenuous to the messages we want to share. Understanding different worldviews and exploring Indigenous and euro-western histories represents a critical first step to fully understanding living and working in northern and rural Indigenous communities. A case highlighting tensions and possibilities ends this first section exploring land acknowledgments as relationship, and how navigating these as a social worker working in a rural and northern setting requires intentional unlearning, and then learning, before any help can be offered or received.

Indigenous Narrative of the Relationship with Land

My given name is Hilton King, which is a name that I use to identify myself within society. When I want all of Creation to hear me, I introduce myself in my Ojibway language as Wahmahtig (Learning Tree). This is very important because I want my ancestors to know that I have not forgotten to keep my language strong as it represents who I am. There are very few fluent speakers in my community and as time goes on, I can see how the loss of language, land and displacement of our people affects us socially and spiritually. I come from a small, northern community 300 kms north of Toronto, called the Wasauksing First Nation. The overall population is 1,073 with 379 living on reserve with a land base of 7,874 hectares. Every two years the First Nation holds an election appoints one Chief and five councillors who politically and socially administer the community. The programs and services offered to the First Nation members include day care, a band school, health station, adult learning centre, community centre and an Elders’ residence. Most of my family still reside there with some living off reserve.

In my Creation Story, I know that my name has a big part in my identity. My connection to Creation allows me to be who I am because my name, Wahmatig, (Leaning Tree), is how I am identified in Creation. Had my parents known the teachings of traditional life, my identity would have been nurtured as Anishinaabe. My Creation story has been told within the Mediwiwin Lodge Medicine Society as well as in The Mishomis Book. This Creation story tells of how we came to be as Anishinaabe peoples.

We all have different responsibilities and for me as part of Creation, I believe I am here because this is part of my life journey. In my journey, I attend to spirit by using my medicines and teachings to help me live a good life. My learning has also taught me not to forget how my culture changed my life. Understanding that my spirit was always kind and caring is a huge awareness for me. My Christian training took that away, and I always felt I was not good enough, not lovable enough, and that I would never amount to anything. I can say from the bottom of my heart that my faith in our ways and creation saved me, and I will forever be grateful for who I am.

The Creation Story and the Relationship to Land

Within the Creation story there are seven sacred fires of Creation. Each sacred fire tells of a time in Creation that brought forth life. Each fire is a teaching of how life unfolds from the Creator’s sacred intentions. Each sacred fire tells us of the gradual unfolding of Creation with the first fire speaking to the Creator’s first thoughts and it is from this first fire that we continue today to use shakers in our ceremonies to emulate the Creator’s first thoughts, or the sound of those thoughts. The second fire speaks to the forming of the stars within Creation and then came the moon and sun and duality was formed. This was the third fire in Creation. Each fire signifies the Creator’s work.

Gitchie Manido, also known as the Great Spirit, took four parts of Mother Earth and blew into them using the sacred shell. From the union of the four sacred elements and his breath, man was created. It is said that Gitchie Manido then lowered man to the earth. Man was the last form of life to be placed on Earth. From this original man came the Anishinabe people. The intentions of our life as Anishinaabe people and as the last ones to be formed tells me that we are to help maintain balance and harmony within Creation. Because we were the last to be formed, we must always show our respect for the life that the rest of Creation gives to us, including caring for the land.

The land we have been delegated to live on by the government of Canada is getting smaller as our communities grow by the numbers. There was a time in our history where we had no boundaries and we roamed all over Turtle Island to hunt, gather, build our homes, and raise our families within Creation. We did not abuse the land because we knew that we only had one Mother Earth and it was up to us as the keepers to help her help us to survive here. We realized that if her waters became undrinkable, her air polluted, her back filled with garbage, none of us would survive. Only the animals would survive because they know the teachings of how to live in harmony with Mother Earth.

Since 1492 with the coming of another race to our Island, our lives were changed forever. This was in our prophecy, and it was said that this other race would either bring peace and good will or they would bring a life of hurt and pain to us as a people. As we can see in our history, Indigenous people of Canada have been marred by hurt and pain caused by foreign ways of living. Our ancestors were wise and could see that the other race who came here intended to stay which is why they felt treaties must be developed that respect everyone, particularly the land.

In Canada’s history, they say the Royal Proclamation is the Magna Carta of treaties; however, when this treaty was written there was no input from our leaders. This document also states that we only have the right to use the land, but we cannot own our land. In the Indigenous worldview, the only treaty we recognize and respect is the Wampum Belt Treaty that was developed by all the Nations of Turtle Island under the watchful eye of the Creator. This treaty symbolizes that we all can live together but must respect each other and respect Mother Earth by traditions. There are many Wampum Belt treaties in our history and the Two Row Wampum was the treaty that symbolized that we can all live here and go down the same river, but no one can interfere in each other’s life and how they live. This treaty belt was made physically from all the elements of Creation as opposed to a piece of paper such as the Royal Proclamation.

I am hoping I have given you enough understanding to come to your own conclusion on why this land we walk on is sacred and we must respect her.

Euro-western Narrative of the Relationship with Land

This next section is written from the worldview of a euro-western educated settler who is now an academic in social work. My name is Colleen McMillan and my understanding of the land comes from my primary and secondary education that is informed by a white, settler and colonial version of history.

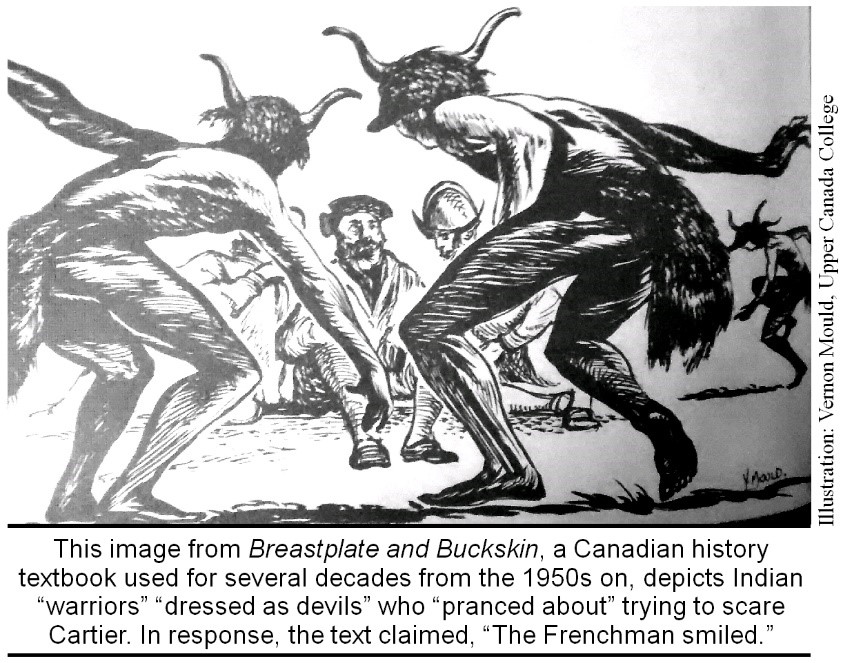

My primary and secondary education emphasized the conquest of North America by men such as Christopher Columbus, Jacques Cartier and John Cabot, all who accidentally discovered Canada while seeking a way to Asia. My knowledge of Indigenous people and the land they owned came from several textbooks I was given as a student during the 1970s, including Building the Canadian Nation, by George W. Brown, and Breastplate and Buckskin, by George E. Tait. The textbook, Building the Canadian Nation, was authorized for use in the schools of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Saskatchewan by the Protestant Committee of the Council of Education. Tait, who authored Breastplate and Buckskin, received the McGraw-Hill Ryerson Special Book Award in 1978 for outstanding contribution to Canadian education and as a model of how to present historical educational material on Indigenous life to primary school students.

Figure 1

Breastplate and Buckskin

Both textbooks depicted Indigenous peoples as savages who attacked early explorers, making conflict a necessary way of life. The use of witchcraft and a connection to the occult inferred they were to be feared and not trusted.

Figure 2

Breastplate and Buckskin

I was taught in school that land acquisition was negotiated by Indigenous peoples and European explorers. I was told the explorers would need land to establish settlements and the Indigenous peoples were happy to share their land and knowledge. This notion continued for many decades in schools, past my primary and high school education. As recently as 2017, a Canadian textbook for grade three children contained the phrase, “when the European settlers arrived they need land to live on. The First Nations people agreed to move to different areas to make room for the new settlements” (Lee-Shanok, 2017). My primary, secondary and even university education relating to land was that it was willingly given to white settlers by Indigenous peoples in exchange for firearms and tobacco. Rich and abundant resources freely allowed explorers, and later other colonists from Europe, to take as much land as needed for purpose of settlement. I was also taught that treaties were created with good intention and Indigenous peoples greatly benefited from such treaties. My early education instilled in me the worldview of early European explorers as benevolent and kind toward their Indigenous hosts, and any conflict was the result of the latter peoples’ not being civilized.

New Social Work Graduate Narrative of the Relationship with Land

You may be wondering what learning about the history of the land and worldviews have to do with social work practice in northern and rural communities. The answer is everything. The history of the land is the context. The differences between Indigenous and euro-western relationships to land is the context. The social work case study will make explicit what unlearning needs to occur before practice can begin in a way that does not reproduce harm. My name is Natalie Compagna, and I am a recent social work graduate from a School of Social Work whose social work program was framed by euro-western pedagogy. My education left me unaware, uninformed, and unprepared for working in a rural and northern Indigenous community.

Case Study Demonstrating the Importance of Unlearning and Learning

During the third year of the Bachelor of Social Work program I moved to a rural and northern community with a population of approximately 580 people. Shortly after moving there, I began working for a Provincial Child Protection Agency that provided services to seven different Indigenous communities in the area. Much of my time was spent trying to connect community members with more resources and supports. Many of the resources and supports required did not exist in our area so we had to refer people to surrounding communities. There were two available options: a small mountain town forty-five minutes southeast, or a city an hour and a half northwest.

When I began working my assumption was that the general preference would be to travel to the closest community – the mountain town 45 minutes southeast. My first assignment was to help a mother access more resources. When we met, I presented her with options for referrals. She declined every option I presented from the town forty-five minutes away and asked if I could try to find the same options in the city one hour and a half away. In that moment it became clear that I had missed something, and I felt as though I had completely failed the community member. This scenario would repeat itself multiple times before I eventually approached a co-worker, explained the situation, and then asked, “What is the history and context with the local communities?”

The response from my colleague was more complex than I had anticipated, and immediately I wished I had asked sooner. This reflection highlights the importance of unlearning. The land forty-five minutes away was what many people from one of the local First Nations called home before it was appropriated by European settlers. The Nation of people were removed from their homes, the land taken from them, and they were pushed out of the area. Forced to start over, the Nation resiliently rebuilt their community. However, residual tensions between the local community and the community down the highway were still palpable and very much present.

Shifting from a place of knowing to not-knowing, I asked the mother if she would mind telling me about the tensions associated with the community, I had insisted she go to. She shared many stories about the pain related to how poorly she was treated in the other community because she is First Nations. She suggested that the next time I go grocery shopping I truly pay attention to how customer service is delivered based the shopper. Towards the end of the conversation, she stated that many people would rather drive further to be treated equitably and with respect.

Unlearning and learning as a way forward

As highlighted in this case study, history informs context, which then informs social work practice in rural and Indigenous communities. It is ideal that new social workers be given a brochure, “Community-Context & How to be a Good Guest,” in order to be well-informed. However, since there is no such brochure, the social worker is responsible for acquiring the necessary information. Although not a brochure, consider the recommended steps below to ensure you begin your practice in a new community in an informed, respectful, and culturally-mindful way.

First Step: Acknowledge you are a guest and are privileged to be there.

If you have moved to a remote or rural northern Indigenous community for a social work position, your first relationship with the land should come from a place of gratitude. It is important to acknowledge that you are a guest on the land and are privileged to be living there. Take time to familiarize yourself with the local landscape. Do not be afraid to venture out into the community and experience what local amenities are offered. Tour around the outlying areas to the north, south, east, and west so that you have a basic understanding of the geography of the area. Next, is a reminder that may seem superfluous, but you should take heed. If you have arrived in a new community with the narrative, “I’m here, I’m going to fix things, I’m going to help, you’re welcome,” then please pack your bags and leave. People do not need to be “fixed”, and you are not a solution (Lamia & Krieger, 2009). Beginning the work with this kind of narrative is guaranteed to mislead you.

Second Step: Get to know the history which informs existing tensions

Entering a new community from a place of not-knowing will serve you well. A place of not-knowing means not making assumptions and being humble in your approach. A good place to start acquiring knowledge is to ask your new co-workers to tell you about the land, the territory, and the history associated with that land. They may have local books, stories, or information to share with you that will serve as useful tools. Ask if there is a local knowledge keeper or community member that you may be able to speak with. Equally important, and this will hopefully become habit, is to ask what gifts or practices are customary if you are seeking knowledge or wisdom from a community member. For example, in some communities it is custom to give a gift of loose tobacco in exchange for the individual’s time and knowledge. Getting to know the area and the history of the land will help you in your social work practice. The earlier you can get this information, the easier it may be for you to provide respectful and informed care.

Examples

Reflection Questions about Land:

- What was your first impression when you read the Indigenous and euro-western approaches to the land? Did you feel there was a connection or disconnection between the two sections?

- Do you know what treaty of land you currently live and work on?

- If you were to identify one lesson you need to unlearn prior to practicing in a northern or rural Indigenous community, what would it be, and how would you plan to unlearn it?

Code of Ethics – Tensions Between two Different World Views

Perhaps the greatest divide between western and Indigenous worldviews is that of ethical codes and related behaviours. In fact, from a language perspective, the term “code of ethics” is absent in the Indigenous worldview. Ways of ethically conducting oneself are legislated in the western world, as compared to relational and wholistic in the Indigenous worldview. Generally, codes of ethics in western centered practice are driven by principles of competencies, risks, and interventions, and they are informed by expert opinion. The Indigenous worldview is relational, starting with acknowledging the relationship with Mother Nature as the Creator. Understanding self allows for behaviour that is balanced, grounding personal and professional behaviour in teachings from the Medicine Wheel, Seven Grandfather Teachings, and the Wampum Belt. As you read through this section identify what you see as shared space, or common factors, between Indigenous and euro-western contexts of professional conduct.

Indigenous Narrative of a Code of Ethics

From an Indigenous worldview, a code of ethics is important to keep us accountable as social workers. Approaching a code of ethics from a place of self-reflection is important to become more attuned to the people we are working with. If we are not in a good place ourselves, and have no knowledge of other worldviews, we will experience difficulty in having empathy, a necessary trait if one is to be a helper. If we are not coming from this place of understanding, it is not our fault, as western ways of knowing have never taken the time to unpack a history that dates back to settler arrival on the land we call Turtle Island.

I have been fortunate with my social work education journey, because it has been culturally motivated. The undergraduate and graduate programs I attended highlighted the gaps in western healing, and the areas where my Indigeneity would be helpful as a healer with my people and community. Treaties signed between Indigenous people and settlers made us accountable to ourselves and how we could live together as people. Some of those treaties are the Medicine Wheel, the Seven Grandfather Teachings, and the Wampum Belt.

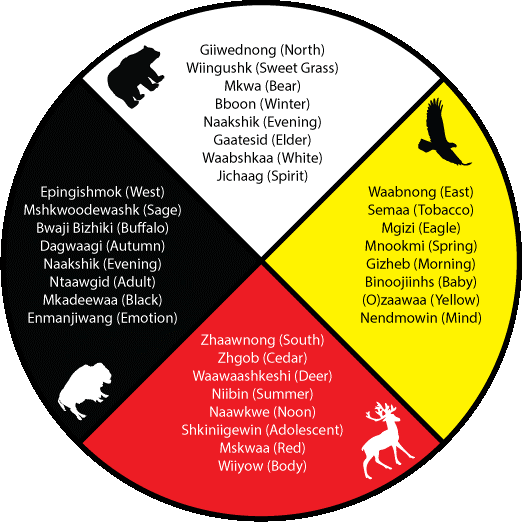

The Medicine Wheel

The Medicine Wheel teaching is a guide to living, teaching us that if we follow this guide, our connection to Creation will be filled with harmony and balance. If we think of the Medicine Wheel as an actual wheel, the wheel is incomplete if any colours of peoples are missing. This tells us that society has excluded colours from this wheel resulting in an unbalanced wheel, which means we have an unbalanced society. Our history tells us that this understanding is rooted in truth. Exclusion of people because of their skin colour or different beliefs is evident in the prevalence of racism and domination in our society.

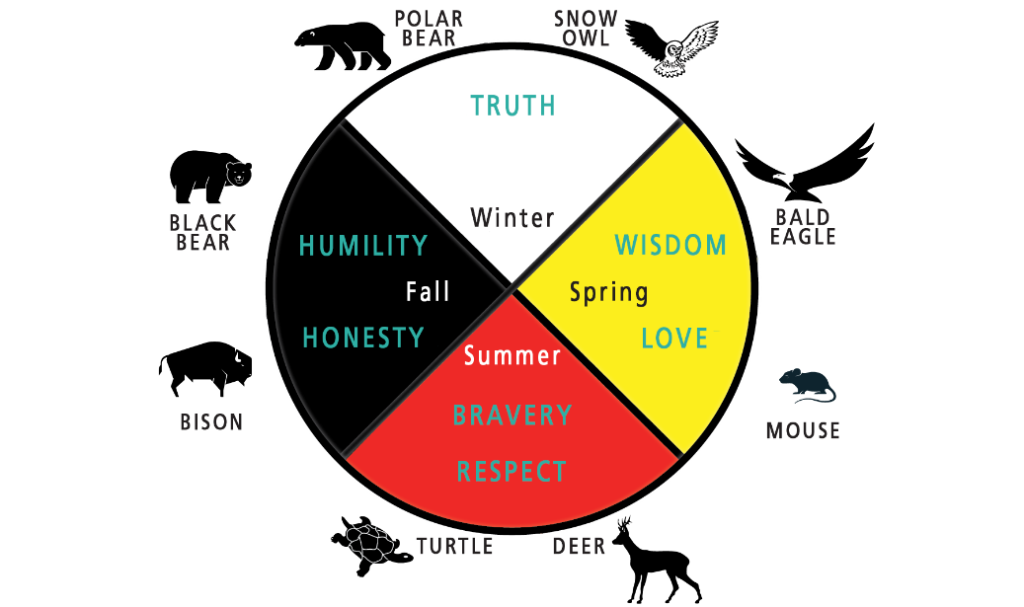

Figure 3

The Medicine Wheel

In Medicine Wheel teachings, everyone has a right to a good life and no one is excluded (Absolon, 1993). The colors in the wheel represent the four colors of men/women: red, yellow, black and white as illustrated in Image 1. There are animals who sit in those directions and deserve the same type of respect we give each other as human beings because we are all part of Creation and are interrelated. A book titled “The Hollow Tree “by Herb Nabigon (2006) is a reading that reflects a wholistic approach to healing and incorporates the four sacred directions that give us meaning in our social work practice. For example, in the east we receive new beginnings, the south is about relationships and summer, the west is about gathering and preparing, and the north is a time for storytelling and rest. Each of these directions applies to an element of our being: spirit, heart, mind and body. Together, these elements create a wholistic and balanced practice.

From the beginning of our time, we as Indigenous people knew and respected this worldview as a way of being—not a religion but a way of life. We were instructed to live in harmony and balance within Creation. We were created out of love from Mother Earth, father sky and our grandparents—grandmother moon and grandfather sun.

The Seven Grandfather Teachings

Our belief system is founded upon guiding principles referred to as The Seven Grandfather Teachings seen in Image 2. These teachings guide us on how we should conduct ourselves toward each other and Aki Kwe (Mother Earth). They keep us connected in a way that reminds us that anything we do within the context of Creation, we do always under the guise of Creation to keep us humble. The Seven Grandfather teachings tell us if we do not believe in something, there may be disruptions resulting in a path that is harmful, because we are out of balance and harmony with Creation. Much like the Medicine Wheel teachings, the Seven Grandfather teachings also guide us toward living a good life by following principles; wisdom, love, respect, bravery, honesty, humility and truth. Creator wanted us to live life to the fullest and he/she gave us all the tools to do this, but they all must begin with self.

Figure 4

The Seven Grandfather Teachings

Indigenous people believe we experience a state of disharmony or imbalance in our lives because we have strayed away from the teachings of the Seven Grandfathers, fundamentally the lack of respect for self (Rakafa, 2018). Again, the interconnectedness of the Seven Grandfather teachings reflects a synergy between one’s core beliefs and one’s behaviour or practice; for example, to have truth you must have courage, to have honesty you must be brave, to know love you need to know peace, and to know wisdom you must practice humility. Indigenous people apply these teachings to all of Creation, not just human beings.

The Healing Power of Circle Work

Indigenous authors such as Absolon (2011) Wagamese (2019) and Mitchell (2018) write with spirit about how connected we are to the land, wind, water and sky. We embrace our traditional ways allowing spirit to come and be celebrated, such as when our circles open with ceremony. When spirit is present, we feel supported to be honest, not to be afraid of sharing our personal stories, and to talk openly and with authenticity in circle. As social workers, it is important we also talk honestly in these circles because of the people we are helping. By sharing our own thoughts and insights we allow the pain and suffering of others to be told without judgement or fear of being shamed.

Our circle consists of people from east to west and teachings from those locations. This concept looks at life as circular and emphasizes that everything is related. In Rupert Ross’s (2006) book, Returning to the Teachings, he explains how the circle can bring harmony and balance back to people who end up in the justice system. He writes that in the legal system there is a winner and a loser, which erects a barrier to healing. In small and rural Indigenous communities this emotional divide is very damaging and creates residual harm. When a circle is used to facilitate conversation between two parties, all people who live in that community are invited to come and participate if they wish. recognising the principle that harm extends beyond the individual. The four sacred medicines of tobacco, sweetgrass, sage and cedar are placed in the middle of this circle to help bring the spirit of these medicines into the circle. The medicines are placed in their respective direction to honour the belief that ancestors sit in those doorways and can be called to help at any time. A facilitator familiar with Aboriginal beliefs guides the circle aligned with the spiritual component of Indigenous beliefs. An Eagle feather is given to each participant who speaks to support the sharing of truth. The knowledge that is shared validates Indigenous thought, which supports multiple perspectives and truths given through honesty and authenticity. The circle brings people together with a feeling of kinship. I believe this blood memory has taken its place to bind us together.

Teachings of the Wampum Belt

The Two Row Wampum Treaty defines how we are to go down the same river of life together: Indigenous people stay on our side of the river and settlers stay on their side of the river, and we are not to interfere with each other’s way of being and knowing. This parallel journey is reflected in Image 3 with the two lines that are equal but do not intersect. Unfortunately, this agreement was never followed although for Indigenous people, our worldview has not changed, and we still believe that all people have an inherent right to a good life.

Figure 5

The Wampum Belt

Corbiere (2014) explains how the Wampum Belt is a symbol of a worldview connected to the land and spirit world and a reminder to settlers of historical agreements. Theses agreements were made under the watchful eye of Creator and acknowledged the sacredness of treaty discussions toward a world that all people live in harmony and balance. Unfortunately, these understandings are no longer acknowledged or followed by settlers and a disconnect from Creation is the result. As with other Indigenous ways of knowing, the Wampum Belt is symbolic of the deep and scared relationship to the land. Indigenous peoples see land as our Mother Earth and do everything in their power to help preserve her.

Euro-Western Narrative of a Code of Ethics

Euro-western codes of ethics for social work have transitioned through several different stages over the last century, suggesting either an evolution or a search for meaning, depending upon one’s perspective. Reamer (1998) identified four spans in which the profession’s code of ethics can be understood: the morality period, values period, ethical theory and decision-making period, and lastly the risk management period that predominates today, particularly in child welfare. While the morality period reflects the Christian charity or non-profit origins of the social work profession, on organizing relief and responding to the “curse of pauperism” (Paine, 1880, as cited in Reamer, 1998), there remain paternalistic elements within the context of social work and Indigenous peoples.

The period in which the concept of morality dominated was the era of residential school systems (1876-1996). The forceable removal of thousands of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit children from their homes by provincial welfare workers was most evident during the 1960s, also known as the 60s Scoop. The intersection of religion and charity, both concepts underpinning social work ethics, assumed the form of government sponsored religious boarding schools toward the goal of assimilation into euro-Canadian culture (Union of Ontario Indians, 2013). The failure of this government intervention set the context for the 60s Scoop, when social workers assigned to reserves acted as agents of the state in the apprehension of children. Social workers at that time were not required to have specific knowledge about, or training in, Indigenous child welfare or First Nations culture. Trained in the western worldview and supported by a code of ethics that guided their actions, social workers “were not trained to recognize problems rooted in generations of trauma related to the residential schools” (Kawartha-Haliburton Children’s Aid Society, n.d., para. 1). Societal views existing at this time were used to justify the systematic disruption of families as necessary through the involvement of social workers; Indigenous peoples were regarded as “child-like creatures in constant need of the paternal care of the government. With guidance, they would gradually abandon their superstitious beliefs and barbaric behaviour and adopt civilization” (Titley, 1992, p. 36). Equipped with “good intentions,” child welfare workers, unfamiliar with child-rearing practices and communal values, “attempted to rescue children [without] taking culture and ethnicity into consideration as it was assumed the children would take on the heritage of the foster/adoptive parents” (Alston-O’Conner, 2010). Contributing to the morality stance was that of monetary gain; provincial child welfare organizations received monies for each child apprehended (Lavell-Harvard & Lavell, 2006). The transfer of Canadian Aboriginal children to the United States served as an additional financial gain as private adoption agencies paid child welfare services in the amount of $5,000 to $10,000 per child (Lavell-Harvard & Lavell, 2006). Child welfare policies actively supported social workers to “remove Aboriginal children from their homes and communities and damage Aboriginal culture and traditions all the while claiming to act in the best interest of the child” (Johnson, 1983, p. 24).

Parallel to these activities was the development and expansion of The Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW), founded in 1926 with the first code of ethics offered in 1938. The initial code was revised eight times since 1938 with the most recent revision in 2005. In Canada, while social work legislation is the responsibility of the provinces/territories, provincial codes of ethics reflect and uphold the values listed by the CASWE to guide social work practice. These include (CASW, 2005):

- Value 1: Respect for the Inherent Dignity and Worth of Persons

- Value 2: Pursuit of Social Justice

- Value 3: Service to Humanity

- Value 4: Integrity in Professional Practice

- Value 5: Confidentiality in Professional Practice

- Value 6: Competence in Professional Practice

Despite the multiple revisions to the CASW Code of Ethics, several scholars have critiqued the code for failing to recognize the historical role of power embedded in the values, with more emphasis placed on protecting the profession than the pursuit of social justice. For example, Collier (1993) considers the relationship between social work and practice in remote and rural areas to be a residual effect of colonization. He argues the social work profession has traditionally reflected control and regulation, serving dominant society’s interests of agency bureaucracies, rather than the interests of Indigenous individuals or their communities (Collier, 1993). In a 2010 Master’s thesis, Marques (2010) explored to what degree the CASW’s six values transferred to practice in northern, rural and remote communities, defined as communities north of the 54th parallel. A key finding of the study that interviewed social workers working in rural and northern communities, including reserves and with band councils, was that the CASW Code of Ethics (2005) did not align with the rural and northern context in which they worked. Value misalignments identified by Marques (2010) in her thesis, “Applying the Canadian Association of Social Workers Code of Ethics in Uniquely Situated Northern Geographical Locations: Are there factors in practice environments that impact adherence to the 2005 code?” are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Misalignments between CASW Values and their Applicability to Rural and Northern Practice

| CASW Value | Value Misalignment |

| Value 1: Respect for the Inherent Dignity and Worth of Persons | Challenges providing direct service to clients in their home communities – community norms, existing/non-existing community structures/ programs/services, and multi-service collaboration

Challenges with the justice system and child welfare system – social justice is not served, political games |

| Value 2: Pursuit of Social Justice | Limited Resources – lack of positions and funding

Service provision in home community – (community leadership challenges, community power structures, accessibility, resources, service provision environment, community supports |

| Value 4: Integrity in Professional Practice | Social worker role challenges – holding a social work degree, qualified, experienced, competent, specialization expectations

Challenges with supervisor role – non-degreed, unqualified, lack of access, lack of support, lack of knowledge Nepotism – power structures, positions provided to unqualified family members and/or friends, impacts the quality-of-service provision, impacts clients directly |

| Value 5: Confidentiality in Professional Practice | Boundary challenges – dual and multiple roles

Confidentiality challenges – professionalism, service environment, privacy, community population, accessibility to community, service provider community-based versus itinerant |

| Value 6: Competence in Professional Practice | Unrealistic expectations of service provision – beyond area of competence, lack of specialization

Geographical location – accessibility, existing services/supports, and jurisdictional challenges |

(Marques, 2010)

Christian eurocentric values frame the CASW Code of Ethics (Vanderwoerd, 2010) so it is not surprising that the code’s transfer to practice is experienced as problematic and incongruent to the living and working contexts in rural and northern communities. Two foundational concepts of the CASW Code of Ethics have been earmarked by the Ontario Human Rights Commission as problematic in the context of Indigenous children continuing to be overrepresented in the child welfare system: decision making and risk management. Perceived bias of authorities, including child welfare workers, has been reported in decision making practices related to assessment, resulting in higher rates of risk being assigned to Indigenous families. In the report, Under Suspicion: Concerns about Child Welfare, The Ontario Federation of Indigenous Friendship Centres have identified that non-Indigenous child welfare workers, do not understand the nature or structure of Indigenous families and cultural differences in how families live. They only see that children are not being raised by their parents or are living in what they think are over-crowded conditions. In another example, Indigenous youth told us that they are sometimes put into care because they miss a lot of school due to practicing their traditions and taking part in ceremonies. (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2017)

Additionally, risk assessment and tools used to assess risk are perceived to “be biased and perpetuate racism because they do not account for structural inequalities, such as racial discrimination, that may affect a child’s well-being” (Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2017). To extend this argument further, structural inequalities leading to poverty are stated to result in value judgements against Indigenous parenting practices by non-Indigenous social workers. Standards for assessment are based upon white, western and Christian worldviews which fail to consider cultural knowledges, values and beliefs.

New Social Work Graduate Narrative of Code of Ethics

An Elder I was working with offered me traditional medicines, and performed a smudge ceremony as a gift for helping her. The Elder explained to me that I owe her a package of tobacco for the medicines. In that moment, the western and Indigenous approaches to value and ethics collided. Professional boundaries in the social worker and client relationship are important. As outlined in the CASW (2005) Code of Ethics, value 4 and principle 3 states, “social workers establish appropriate boundaries in relationships with clients and ensure that the relationship services the needs of clients” (p. 7).

I was not able to call a “time-out” so that I could quickly shuffle through my textbook on how to handle the situation. Furthermore, I did not even know where I could look to inform myself on this situation. In the moment I had to use my judgement and gut instincts. This was not the first Northern Indigenous community that I have worked with, so I knew that a cardinal rule is to never turn down a gift from an Elder as a helper. It would be insulting to the Elder and may harm the working relationship. Farrah (2012) notes that “giving or receiving a gift that extends beyond acceptable gestures, such as a cup of coffee, a meal or a holiday hamper, can change the professional nature of the social worker – client relationship” (p. 4). In the context of the local community, having someone gift me with medicines is not only considered an acceptable gesture, but an honour.

Accepting the gift was resolved, but I still had to contend with the ethical dilemma of presenting the Elder with the gift of tobacco. At this point I had only been working in the area for three months so was not familiar with local traditions. The first step I took was to consult with a supervisor who was from the community and a band member about local traditions, specifically around gift giving for Elders. I was able to maintain confidentiality while presenting the scenario. My supervisor provided me with insights which included the type of tobacco to purchase, where to purchase it, and the best way to present it. She agreed that accepting the gift and providing tobacco was the best course of action.

The immediacy of this interaction straddled me between honouring the CASW Code of Ethics (2005) ingrained in my western framed education, and that of respecting and paying homage to the relational importance of the local Indigenous context. The crux of the situation was how to find possible middle ground between the CASW Code of Ethics while being respectful to Indigenous ways of knowing and living. In practice, I heard colleagues say, “this is the way it is up north” or this is the “northern way.” There is truth to this, but we still have ethical obligations and standards as social workers. Finding the path between these two worldviews is contextually bound, requires an openness to unlearn and then learn local ways while being mindful of the legislation that we have agreed to practice by.

Examples

Reflection Questions about Ethics:

- What does ethics mean to you?

- Does this section change how you view the Code of Ethics? If so, in what way?

- How would you adapt your personal and professional code of ethics to local Indigenous culture in the treaty area where you live?

Epistemological Contexts – Multiple Knowledges are Important

Epistemology is a branch of philosophy focusing on the theory and creation of knowledge (Stroll & Martinich, 2021). Willig (2019) argues that a core skill needed to be an effective helper is to have an awareness of one’s own epistemological underpinnings, or what kinds of knowledges(s) are valued. For example, does the knowledge that informs one’s social work practice comes only from a euro-western worldview, or recognize different forms of knowledge(s) such as those created by Indigenous peoples?

In the same way researchers need to develop awareness of their assumptions about what there is to know and how they can come to know about it (epistemology), social workers need to be aware of their fundamental assumptions about human beings and the world they live in, as well as their beliefs about how best to develop an understanding of their clients and the meaning(s) of their experiences (epistemology) (Willig, 2019).

In this section we will focus on Willig’s description of epistemology as it relates to the act or process of counselling in social work. How do you provide counselling? What are you taught about the dimensions associated with counselling; as in where does counselling take place, when does it happen, and what proof exists that it happened?

Indigenous Narrative of Knowledge

Every Nation, community, and individual has their own preferences regarding social work practice. It is essential to recognize that there are multiple ways to provide individual, community-centred and culturally safe services. Otherwise, there is a risk of perpetuating colonized and oppressive approaches that will not provide space for healing but cause more harm (Stewart et. al., 2017). One of the key differences between Indigenous and western practice is the shift from individualistic counselling approaches to more collectivist ways, regardless of whether it represents an individual or community intervention. Some Indigenous worldviews of practice may be indicative of more collectivist societies, such as healing and grief circles. McCormick (2000) notes that more meaning may be provided through community, cultural values, and family. Healing circles are an example of combining all three of these elements.

The way Indigenous peoples approach healing is spiritually guided and mindful of the Seven Grandfather Teachings, the role of the Creator, and beliefs and practices referred to as traditional medicine. The Report of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (1996) defined traditional healing as,

Practices designed to promote mental, physical, and spiritual well-being that are based on beliefs which go back to the time before the spread of Western ‘scientific’ biomedicine. When Indigenous peoples in Canada talk about traditional healing, they include a wide range of activities, from physical cures using herbal medicines and other remedies, to the promotion of psychological and spiritual well-being using ceremony, counselling and the accumulated wisdom of Elders. (p. 348)

Traditional healing work is relational, ceremonial, and sacred. There are several avenues that are used to support people who are struggling and in need of healing. Some of the approaches will be described here but it is important to recognize the importance and role of context with each of these approaches. For example, some Nations will use the sweat lodge while others will not. Likewise, some ceremonies associated with the sweat lodge are unique to that particular community. For example, some ceremonies may include drumming and gift offerings to the ancient ones, while in other cases it could be part of a Sun Dance (Marsh et al., 2018). Assuming all Indigenous peoples follow the same healing approaches risks homogenizing people and sacred practices and reproduces colonization.

The Sweat Lodge

The sweat lodge has been used for generations and carries great significance. Those who carry the gift to facilitate this ceremony are ones who have spent many years learning, and can be a woman or man who is trained by Elders to facilitate sweats. They are aware of how sacred this ceremony is because their training has taught them; they know they are dealing with spirit. The ceremony is about purification of the mind, body, and soul and when one goes through this ceremony, they are going back to the beginning when life was safe for them.

Elders teach that the sweat lodge ceremony serves a sacred purpose through the ritual healing or cleansing of body, mind, and spirit while bringing people together to honour the energy of life. I spoke to Elders Julie & Frank Ozawagosh (personal communication, January 2013), about the teachings Elders bring to the Sweat Lodge. The Elders teach that each person who enters the lodge brings his or her own challenges, suffering, conflicts, addiction, and concerns. Sitting together brings connection, truth, harmony, and peace through sweating, praying, drumming, sharing, stories, and singing (Marsh et al., 2018). All the elements of the lodge come from the land and whenever lodges are built, the worldview is that healing will happen, but first faith must be reached by the individual who is asking for healing. Some lodges are envisioned and crafted as circular to represent the Mother’s womb, and resembles a baby bump when it is sitting on the land. This is aligned to the stages of life teachings, that talk about how we were carried by our Mother for nine months. In those nine months we were surrounded by water and the heartbeat of our Mother, so if we can borrow from that beautiful image, this is the safest we will ever feel in our lives and provides the ultimate place of security for healing. This author used the sweat lodge for healing from the trauma of sexual abuse while in the care of the Children’s Aid Society. My experience in the Sweat Lodge helped me feel that I could trust people again.

Healing Circles

Healing circles, or talking circles, are ceremonies that create space for connection, culture, and healing. When someone passes away in the community there is a collective grief, and the entire community feels the impact of the loss. Coming together, supporting each other in a safe and sacred circle can be powerful. Healing circles take a variety of forms, but a shared element is that members sit in a circle to consider a problem or a question (Mehl-Madrona & Mainguy, 2014). First Nations peoples observe that the circle is a dominant symbol in nature and has come to represent wholeness, completion, and the cycles of life, including the cycle of human communication.

Indigenous healing using circle work starts with a prayer, usually by the person convening the circle, or by an Elder, if an Elder is involved. The way the circle is conducted speaks to the collectivist nature of Indigenous epistemology. This is reflected by the circle keeper saying only few things about the talking object and then passing the object to the person on the left, clockwise. As a healing circle, smudging will often begin the ceremony, to invite the spirit world in and feel connected. Someone will typically go around the circle holding the abalone shell with the medicine and an eagle feather in their right hand. Each person in the circle smudges. A talking stick or other representative object is held by the person who speaks. Other sacred objects may also be used, including eagle feathers and fans, a sacred shell, stone, or Wampum Belt.

Figure 6

Sweet Grass and Feather Used for Smudging Ceremony

Respecting knowledge is multiple, experienced differently for each person, and listening is important for healing; only the individual holding the talking stick speaks whiles others remain in respectful silence. The circle is complete when the stick passes around the circle one complete time without anyone speaking out of turn. The talking circle prevents reactive communication and directly responsive communication, and it fosters deeper listening and reflection in conversation. It also provides a means for people who are prohibited from speaking directly to each other because of various social taboos to speak and be heard. The sacredness of circle work follows Indigenous epistemology in that it honours respectful silence, speaking from the heart, authenticity of emotion and speech, and confidentiality in the circle. Nothing leaves the circle without permission from the speaker.

Time and Place

Time assumes a different meaning when counselling in northern and rural communities. Counselling sessions may be as short as thirty minutes, or as long as an hour and a half if the person you are working with deems it to be important. Allowance is needed to make space for the natural story telling process to unfold, honouring the oral tradition of experience, and not be restricted by the western view of counselling regimes and practice protocols.

Lastly, an office setting may not be appropriate. It is difficult to create a sense of safety in a space that represents generations of systemic racism and biases experienced by Indigenous peoples. Counselling is relational, contextual, familial and land based. Locations of conversations can be determined by the individual and can look like sitting by a fire, going for a walk by the river, or having a cup of tea at a kitchen table. A connection that is not forced, and feels more organic, has more potential to create a space for healing.

Euro-western Narrative of Knowledge

Individuals planning a career in social work practice are met with several mid-level theories of counselling, estimated to be between 200 to 400, to choose from (Lambert et al., 2004). Western approaches to counselling traditionally create foci of practice by organizing theories into different groupings; psychodynamic theories, cognitive- behavioral theories, humanistic theories, feminist theories, and postmodern theories. Organizing theories this way represents a western classification system that is discrete. There is no acknowledgement of context, or how the theories relate to the land or the community. The dimensions relating to counselling emphasize location, duration, treatment protocol and documentation. These dimensions are standardized, apart from feminist practice that is aligned to power dynamics and the relational and reciprocal aspect of the client/worker relationship.

Historically, students enrolled in schools of social work informed by western theories were taught that the problem lies within the individual. A shift during the early 2000s witnessed a shift to a strengths-based perspective. As described by Saleebey (2009), the “fundamental premise [of strengths based social work] is that individuals do better when they are helped to identify, recognize, and use the strengths and resources available in themselves and their environment” (p. 234). Despite this shift, there continues to be a disregard for Indigenous epistemologies in program curriculum. Looking at some of the ways current ontology and epistemology is taught and practiced highlights the reproduction of euro-western centric thinking.

Location of Counselling

Counsellors are often taught to hold sessions in offices or other spaces within a building. If not in an office specifically designated for counselling, then counselling is typically held in an agency, school, shelter or hospital. Counselling in an office is usually one hour in length, after which the individual, couple or family leave. Studies suggest the ideal space with respect to furniture, lighting, artwork, and seating (Devlin & Nasar, 2012; DeAngelis, 2017). In an article titled, “Healing by Design,” DeAngelis (2017) states that

a good therapy office design should take into account the human instinct to protect ourselves and our territory—a feature that may be particularly important to consider with vulnerable therapy clients. We are animals, after all, and do our best mental work when we feel a little bit protected. (p. 56)

This concept of protection relates to the social worker, not to the client, and continues to be emphasized as important as evidenced by the recent literature. In the context of working with Indigenous peoples, the historical violence done by the social work profession is unrefuted. Suggesting that social workers need to protect ourselves and our territory is reminiscent of settler narratives inferring Indigenous peoples were “dangerous savages” (Garcia, 1978) and the guarding of appropriated land is still necessary.

Other literature supports the use of credentials in the room to demonstrate the social worker’s expertise (Devlin et al., 2009), noting that four to nine displays of professional credentials is sufficient to showcase within the office. The authors were unable to locate any academic western informed literature that included the importance of land acknowledgment in the offices of social workers, especially during this historical moment in the context of the Truth and Reconciliation Report in Canada. The absence of such literature in academia speaks to the erasure of the importance of settler acknowledgement, thus reproducing western dominated ontology of counselling.

Risk and Safety

The concepts of safety and risk are reflected in how social workers are instructed to practice and carry out their respective roles and responsibilities. Much has been written and taught on risks associated with the profession (McCafferty & Taylor, 2020) specifically in the field of child welfare. Despite the growing awareness of harms caused to Indigenous children and families as identified in the report, “Understanding Risk in Social Work” (2017), support continues for “robust assessment tools [to] provide a necessary check and balance in emotionally demanding work” (p. 376). In this way protection of the social worker is central, not the individual or family client. As noted earlier, risk is a concept that permeates throughout much of western social work literature, ranging from office arrangements, to assessments, to documentation. Barsky (2010) states that the continuing rationale for risk management and related policies is to avoid the legal consequences of causing harm, which include lawsuits, disciplinary action, or damage to the employer’s legal status or position in the community. This principle is operationalized in how Schools of Social Work teach students documentation that is risk as compared to strengths based.

The emergence of evidence-based practice modalities, such as cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT), removes land and environmental context from counselling and reinforces the problem is the person argument. Such modalities reinforce a standardized approach to understanding issues experienced by the individual and are divorced from historical, social and environmental impacts such as intergenerational trauma and residential schools. Documentation resulting from such modalities is categorical and discrete, separating personal narratives of the client to be included in case notes.

New Social Work Graduate Narrative Regarding Knowledges

I quickly noticed as a new social work graduate that the space between a euro-western approach to counselling and the Indigenous centrality of relationship within Indigenous communities is evident. This difference first became obvious to me in my role as a Mental Health and Addictions Clinician for a mobile support team; I needed to unlearn what I was taught just a year earlier in a graduate social work program.

As a service provider in a small northern community, no work of any kind can be done without trust. A deep trust must be earned. All interactions are relational, and some may even be experienced as more “casual.” or informal. For example, community members have asked me to have tea to decide whether the element of trust is even possible, before deciding to engage in counselling. I have been asked to meet in parking lots to engage in conversations to determine whether I can be trusted.

This chapter emphasizes the importance of context. How context is translated into the ontology of counselling is that previous history of service providers determines what counselling is and how the community understands it. There may be a history of service providers coming into their small town, “helping” for a short time, and then leaving, with this cycle repeated multiple times. There may be residual hurt and pain from this cycle established by previous service providers. All context matters, as it actively informs the number and degree of barriers local community members associate with the concept of counselling.

The examples given in this section relate to the context of counselling, but also apply to any area of practice or focus under the social work umbrella. Before engaging in any type of social work, one must first start to think about community. It will be difficult to become a part of the community and trusted by the community if you do not engage with it. Become a part of the community by being present, engaging in relationship building, and being visible so people have an opportunity to get to know you. If this is out of your comfort zone, or not something that was ever taught to you in school, consider “non-traditional” western ways in which people in the community can determine whether they can trust you in counselling. For example, I do Ride and Rant.

Ride and Rant is my way of adapting to the trust needs of community members. A couple of community members were not comfortable with meeting in the office setting. I advocated funding to purchase Tim Horton’s gift cards and then offered to pick people up from their home, grab a coffee and go for a ride. One client who I had seen in the office the first two sessions spoke twice as much in the vehicle. My car has proven to be a valuable and context appropriate therapeutic setting. People appreciate facing the same direction as a sign of relational equality.

Social work in a northern context is about the space created to reflect relationship. Going for a walk in the woods, being outside on the land, talking while walking, sitting by a fire, all symbolize respect for the context of northern Indigenous communities. I sat with an Elder in her garden to have a counselling session because that was her happy place, during a particularly difficult day. Euro-western approaches to working with community members may feel inauthentic, lacking in relational connection and hierarchal because of the physical location in which most social workers are taught to practice in, the office.

Examples

Reflection Questions about Knowledge:

- How did you come to know what social work is? How do you know what you have learned is true?

- Does the way you practice social work support or diminish Indigenous epistemologies? Can you provide an example?

- How would you change your current way of counselling to meet the contextual needs of the community you are working in?

- How do you establish a relationship with the community to empower individual members?

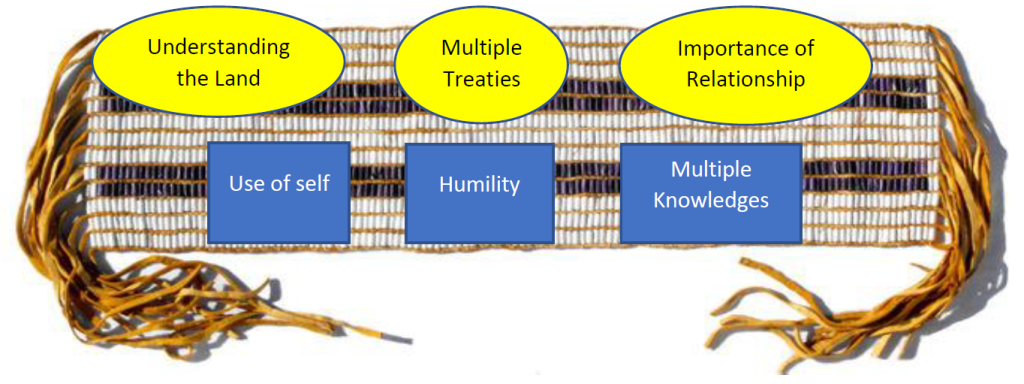

Moving Forward – Creating an Epistemological Wampum Belt

In this final section we offer a way of moving forward that honours Indigenous worldviews while curating western ways of working that contribute and support social workers employed in rural and northern communities. This section is framed by the teachings held in the Wampum Belt. As previously noted, the Wampum Belt is a symbol of a worldview that is connected to the land and spirit world and a reminder to settlers of historical responsibilities, which has taken on greater significance since the discovery of the residential school graves. The importance of context has been a constant thread throughout this chapter, and as social workers we need to reflect upon past harms against Indigenous peoples. A first step is to acknowledge Indigenous knowledges as valid and not less than euro-western knowledge.

In this final section of the chapter, we offer hope to you, by suggesting a social work Wampum Belt informed by Indigenous and western knowledges and worldviews that can be contextually appropriate, mindful, and healing.

The Two Row Wampum Belt

The Two Row Wampum Belt (Kaswentha) of the Haudenosaunee is an example of a wampum belt that symbolizes an agreement of mutual respect and peace between the Haudenosaunee and European settlers. The principles were embodied in the belt by virtue of its design: two rows of purple wampum beads on a background of white beads represent a canoe and a European ship. The parallel paths represent the rules governing the behaviour of the Indigenous and European peoples. The Kaswentha stipulates that neither group will force their laws, traditions, customs or language on each other, but will coexist peacefully as each group follows their own path (ahnationtalk, 2015; Gadacz, 2020).

Remaining faithful to the teachings embedded in the wampum belt, while continuing to be reflective and reflexive of context, we created a version of the Two Row Wampum Belt recognizing the western learnings and unlearnings that are necessary to provide mindful guidance to those wanting to practice social work in northern or rural communities. For example, social workers trained in western knowledge first need to unlearn teachings related to the land, treaties, and relationships. Only then can learning happen related to the use of self, the importance of humility and respect for multiple knowledges.

Figure 7

Combined Worldview Two Row Wampum Belt

Indigenous Teachings and Western Competencies Wampum Belt

Aligned with the Two Row Wampum Belt, we envision parallel, distinct but complementary, concepts of Indigenous and western knowledges of social work that acknowledge the importance of context while providing mindful attention to practice. This “social work Wampum Belt”’ is meant to be sufficiently fluid to reflect local teachings and knowledges specific to treaties, geographies and land issues. We have intentionally allowed space in each of the components to incorporate meanings that speak to the different cultural and geographic contexts found in northern and rural Indigenous communities. Lastly, we want to avoid the prescriptive nature reflective of western social work practice that has become the norm in so many programs, and more generally within the counselling field. That said, we are providing a series of guided questions to deepen and extend self exploration toward an understanding of how to work in northern and rural communities. It is our hope that the following set of questions support your journey in creating a Wampum Belt that reflects and respects the living and working context you inhabit. We suggest that you use your answers to create a Wampum Belt specific to the context in which you live and work to practice in a respectful, authentic and relational way in your social work journey.

Land

What is the territory you live on?

What is the history of the land you live and work on?

How should you be acknowledging the land when speaking?

Treaty

What treaty does the Nation belong to?

What is the history of the treaty you live and work on?

Who belongs to the treaty?

Relationships

What languages are spoken in the community?

What language/languages are taught in the schools?

If there is more than one Nation of people living on the land, what is the history between the two? What is the context?

Humility

How does your social location impact how you may be perceived? Consider the context and history of the community.

Have you engaged with the community and made an effort to be a community member?

Dual Knowledges

What have you done to learn more about local culture, traditions, and etiquette?

How have you adapted your practice to be more community-centred?

What changes need to be made to meet the needs of the community?

Use of Self

What are your hidden biases?

What work have you done to engage in self-reflection?

Are you aware of your social identity?

Moving Forward

It is important, and contextually imperative, that we take a moment to acknowledge the ongoing discovery of children’s remains at former residential school across Canada. This discovery underscores the importance of understanding context within social work practice. Those who enter the social work profession do so because of the desire to help, advocate, and make positive changes. The pre-requisite for any change when working in northern, rural areas is to come equipped with an understanding of how this country came to be; how history impacts you as the helper; and how history impacts the people you will be serving. In closing, we are including an interview with an individual who was a career child welfare worker in a rural, northern community to share his lessons and the importance of understanding and accepting context as a key principle. You cannot be a catalyst for change if you do not fully understand how context determines everything and requires unlearning and learning, as well as the space between the two.

Conclusion

This chapter focuses on the importance of context in relation to land, code of ethics and what is considered knowledge for social workers who practice in northern and rural Indigenous communities. Written from the worldviews of an Indigenous social worker, a euro-western educated social worker and academic, and a new social work graduate who lives and works in a northern and rural community, we emphasize the importance of unlearning what one knows, or has been taught, and the resulting lack of knowledge as a starting place. Unlearning requires understanding historical context and how this context informs current social work practice. We end the chapter using the traditional treaty representation of a Wampum Belt to show how Indigenous knowledge and euro-western knowledge can co-exist in harmony when guided by respect, humility, and acknowledgment of context.

References

Absolon, K. (1993). Healing as practice: Teachings from the Medicine Wheel [Unpublished Manuscript]. WUNSKA network, Canadian Schools of Social Work.

Absolon, K. (2011). Kaandossiwin: How we come to know. Fernwood Publishing.

ahnationtalk. (2015, November 20). Alan Ojiig Corbiere: The underlying importance of wampum belts. Nation Talk.

Alston-O’Conner, E. (2010). The Sixties Scoop: Implications for Social Workers and Social Work Education. Critical Social Work, 11(1), 54-55.

Armitage, A. (1995). Comparing the policy of aboriginal assimilation: Australia, Canada and New Zealand. UBC Press.

Barsky, A. E. (2010). Ethics and values in social work. Oxford University Press.

Benton-Banai, E. (1988). The Mishomis book: The voice of the Ojibway. University of Minnesota Press.

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). Code Of Ethics. https://www.casw-acts.ca/files/attachements/casw_code_of_ethics_0.pdf

Collier, K. (1993). Social Work with Rural Peoples (2nd ed.). New Star Books

DeAngelis, T. (2017). Healing by design. American Psychological Association, 48 (3), 56.

Devlin, A. S., & Nasar, J. L. (2012). Impressions of psychotherapists’ offices: Do therapists and clients agree? Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(2), 118 122.

Devlin, A. S., Donovan, S., Nicolov, A., Nold, O., Packard, A., & Zandan, G. (2009). “Impressive?” Credentials, family photographs, and the perception of therapist qualities. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(4), 503-512.

Farrah, J. L. (2012). Examining the complexities of the social worker–client relationship. Newfoundland & Labrador Association of Social Workers: Practice Matters.

Gadacz, R.R. (2020, November 5). Wampum. The Canadian Encyclopedia.

Garcia, J. (1978). Native Americans in U. S. history textbooks: From bloody savages to heroic chiefs. Journal of American Indian Education, 17(2), 15-19.

Johnson, P. (1983). Native children and the child welfare system. Lorimer Publishing. Kawartha Haliburton Children’s Aid Societies. (n.d.). Sixties scoop.

Lambert, M. J., Garfield, S. L., & Bergin, A. E. (2004). Overview, trends, and future issues. In M. J. Lambert (Ed.), Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change (5th ed., pp. 805–822). Wiley.

Lamia, M. C., & Krieger, M. J. (2009). The white knight syndrome: Rescuing yourself from your need to rescue others. New Harbinger Publications.

Lavell-Harvard, D. M. & Lavell, J. C. (Eds.). (2006). Until our hearts are on the ground: Aboriginal mothering, oppression, resistance and rebirth. Demeter Press.

Lee-Shanok, P. (2017, October 3) GTA book publisher accused of whitewashing Indigenous history. CBC.

Marques, L. W. (2010). Applying the Canadian association of social workers code of ethic in uniquely situated northern geographical locations: Are there factors in practice environments that impact adherence to the 2005 code? [Master’s thesis, University of Manitoba]. MSpace.

Marsh, T. N., Marsh, D. C., Ozawagosh, J., & Ozawagosh, F. (2018). The sweat lodge ceremony: A healing intervention for intergenerational trauma and substance use. The International Indigenous Policy Journal, 9(2).

McCafferty, P., & Taylor, B. (2020). Risk, decision-making and assessment in child Welfare. Child Care in Practice, 26(2), 107-110.

McCormick, R. M. (2000). Aboriginal traditions in the treatment of substance abuse. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 34(1), 25–32.

Mehl-Madrona, L., & Mainguy, B. (2014). Introducing healing circles and talking circles into primary care. The Permanente Journal, 18(2), 4–9.

Mitchell, S. (2018). Sacred instructions: Indigenous wisdom for living spirit-based change. Atlantic Books.

Nabigon, H. (2006). Hollow tree: Fighting addiction with traditional Native healing. McGill Queen’s Press-MQUP.

Reamer, F. G. (1998). The evolution of social work ethics. Social Work, 43(6), 488–500.

Ross, R. (2006). Returning to the teachings: Exploring Aboriginal justice. Penquin Books.

Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples. (1996). Report of the royal commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

Saleebey, D. (Ed.). (2009). The strengths perspective in social work practice (5th ed.). Allyn & Bacon.

Stewart, S. L., Moodley, R., Hyatt, A., & Smoke, M. L. (2017). Indigenous cultures and mental health counselling: Four directions for integration with counselling psychology. Routledge.

Stroll, A., & Martinich., A.P. (2021, February 11). Epistemology. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/epistemology

Tait, G. E. (1953). Breastplate and Buckskin [Book Cover]. The Ryerson Press.

Talaga, T. (2018). All our relations: Finding the path forward. House of Anansi Press Inc.

Titley, E. B. (1992). A narrow vision: Duncan Campbell Scott and the administration of Indian affairs in Canada. University of British Columbia Press.

Union of Ontario Indians. (2013). An overview of the Indian residential school system. https://www.anishinabek.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/An-Overview-of-the-IRS-System-Booklet.pdf

Wagamese, R. (2019). One drum: Stories and ceremonies for a planet. Douglas & Mcintyre Publishing.

Whittaker, A. & Taylor, B. Understanding risk in social work. (2017). Journal of Social Work Practice, 31(4), 375-378.

Willig, C. (2019). Ontological and epistemological reflexivity: A core skill for therapist. Counselling Psychotherapy Research, 19, 186-194.