6 Braiding Trauma-and-Violence Informed Care Practice Guidelines into Competencies for Social Workers working in Rural and Remote Locations

Carrie LaVallie and Wanda Seidlikoski Yurach

Trauma-and-violence informed care (TVIC) guidelines and practice policies in human service work impress upon the need to include historical and cultural principles. A culturally comprehensive approach for TVIC is not available for many mental-health providers working in rural, remote, and northern locations in Canada, including social workers. Canada’s colonial legacy created experiences for Indigenous peoples that western[1]-based approaches/practices often overlook and/or cause traumatic triggering. Acknowledging the historical impact colonization has on Indigenous peoples’ health, and understanding the lingering effects of intergenerational trauma, provides key insights into the health and wellness of rural and remotely located Indigenous peoples. Being trauma-and-violence informed “is not about ‘treating’ trauma,” it is about focusing on enhancing safety, control, and resilience (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 3); acknowledging cultural contexts of understanding and healing; and in turn creating psychological safety for both the client and the provider. This chapter braids a trauma-and-violence informed framework and the Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework (Sasakamoose et al., 2017) with social-work practice competencies, creating a more comprehensive approach for social workers working with Indigenous populations in rural and remote communities.

Cultural understandings of healing engage figurative language to explain health concepts. Creating relationships with clients by reducing triggering communication and using a common language can create a trusting space for sharing. Braiding TVIC guidelines, Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework (ICRF), with social-work practice competencies, explores how we explain the same experiences through our beliefs and approaches that support healing. Current healing systems rely on dominant western perspectives; therefore, to create effective decolonized services, social workers need to incorporate treatment and intervention approaches that reflect the worldview of the client. Decolonization is the process of balancing population needs and countering western dominance. Decolonizing the dominant western perspective for trauma-and-violence informed care means prioritizing local understandings of health and harmonizing them with proven western-based methods, within the Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework. This chapter uses the metaphor of a braid to illustrate how social workers blend trauma-and-violence universal precautions that are culturally suitable into their practice. The first section introduces you to TVIC concepts and the second introduces you to the Indigenous cultural responsiveness theory. The third section explains how social workers can harmonize, blend, or braid these three approaches into a wholistic, culturally-suitable healing approach for working with clients who may have experienced violence or trauma. By the end of this chapter, you should be able to describe the principles of trauma-and-violence informed care and the Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework and then use real-world examples to apply them to social work practice competencies for working in rural or remote locations.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will have had the opportunity to:

- Identify power imbalances in rural and remote locations where social workers practice.

- Describe principles of a trauma-and-violence informed framework (TVI).

- Discuss a culturally suitable practice when working with rural and remote clients.

- Critically reflect on alignment of data collection method using universal trauma precautions.

- Apply concepts of Culturally Responsive trauma-and-violence informed care to social work practice.

Figure 1

Braided Sweetgrass

Braid 1 Trauma-and-Violence Informed Care

Trauma-and-violence informed approaches (TVIA) is a way of being that reflects a caring, ethically-based relationship, recognizing “the connection between violence, trauma, negative health outcomes and behaviours” (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 2). Trauma-informed approaches in social work practice presume that clients seeking services may have experienced trauma; therefore, care providers assess for signs/symptoms of trauma and the overall impact on their client’s lived experience. The Government of Canada encourages inclusion of “violence” into the term “trauma-informed” to represent the connection of violence with trauma (2018). Addressing the effects of trauma includes recognizing that violence might have happened in the past or is ongoing and may cause long term-effects (Government of Canada, 2018).

Social work policy and practice should include efforts to understand how trauma and violence impact people’s lives and behaviours. This awareness supports creating emotionally and physically safe environments; fostering opportunities for choice, collaboration, and connection; and providing strength-based and capacity-building approaches to client care. Trauma-and-violence informed social work practice competencies are evidence-informed methods and interventions that include the impact of trauma and violence on one’s life while targeting specific physical, mental, and spiritual health issues seen as overall well-being. Social workers seeking to provide trauma-and-violence-informed (TVI) practice competencies need to employ the following four principles as outlined by Health Canada (Government of Canada, 2018) and are used as guiding principles in this chapter:

- Practitioners understand that trauma and violence impact on peoples’ lives and behaviours. Knowing “exactly” what happened to the client is not as important. as knowing that when someone reacts in an unexpected way, the social worker can reflect upon the possible traumatic or violent incidents that may have been experienced by the person and lead with empathy and understanding.

- Fostering authentic connection and communication in non-judgmental ways helps to build trust and provides consistent expectations to the client. Communication through clear expectations and non-judgement language fosters trust between the practitioner and client, thus resulting in more honest sharing of the client’s lived experience. Honest sharing gives the social worker more information from which to create effective, client-based intervention and treatment options.

- Trauma research and effective treatment is rapidly emerging. To stay on top of evidence-supported methods, organizations and systems can deliver ongoing training and professional development events to foster opportunities for choice, collaboration, and connection with the clients.

- Understanding that dominant service systems often oppress, marginalize, and dismiss trauma-impacted people helps the social worker to anticipate client reactions and needs.

By utilizing trauma-and-violence informed practice competencies and principles, the social worker becomes the intervention approach. Creating a healing environment that includes a safe trusting manner will further improve the effectiveness of the practitioner as the intervention. Unsettling physical or psychological experiences (called a trigger) may cause an unexpected response. To help prevent or lessen triggers that may arise from trauma experiences, it is paramount that service providers set up an emotionally and physically safe environment, using a non-judgmental attitude, offering choice and collaboration, and anticipating client needs. Critical self-reflection, along with clear expectations for the provider, informed by the principles of trauma-and-violence informed care (TVIC), will help professionals to employ strength-based, capacity-building approaches to support favorable coping responses and resilience.

Trauma

Trauma is the lingering memory, either psychologically or physiologically (or both), of a disruptive event that impacts a person’s sense of safety and control; and is defined as “a single event, multiple events, or a set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically and emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s physical, social, emotional, or spiritual wellbeing” (SAMHSA, 2014, p. 4). When the body’s natural defence responses are unable to complete the process of protection or reaction, or supportive resources are not in place to aid feelings of safety and connection, a traumatic response may develop (Levine, 2010): “Traumatized people are fragmented and disembodied. The constriction of feeling obliterates shade and texture, turning everything into good or bad, black or white, for us or against us. It is the unspoken hell of traumatization” (Levine, 2010, p. 355).

Once thought to affect only people exposed to natural disasters or war situations, the concept of trauma has evolved to include explanation from many theories such as developmental, childhood, incident-based, intergenerational, medical, and complex. Intergenerational trauma “is passed on through parental/institutional patterning from one generation to the next, as well as being transmitted through blood lines” (Linklater, 2011, p. 20). Society’s stigmas about one’s gender, race, sexual orientation, ability, and/or culture disproportionately increase one’s experiences of, and effects of, trauma. Lingering effects on trauma-impacted people may present as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) which includes a comprehensive cluster of symptoms profound enough to interfere with one’s family and social relationships, work, and well-being (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Violence

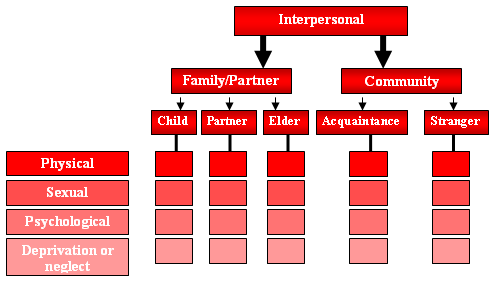

In working with trauma-impacted people, social workers recognize the need to implement an understanding of violence into policies and practice. Violence might be recurring or an isolated incident that has an overwhelming impact on people’s lives. Incidents of violence can be overt, for example, a physical assault; subtle (blocking women’s reproductive rights); or implied, such as systemic racism. The World Health Organization’s Violence Prevention Alliance (VPA, 2021) defines violence as, “the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” (para. 2). The VPA (2021, para. 3) classifies four modes of violence: physical, sexual, psychological attack, and deprivation; and three sub-types: self-directed, interpersonal, and collective. Self-directed violence is injurious actions initiated against oneself such as self-harm or suicide. Violence directed toward another person is coined as interpersonal violence (see figure 2 Typology of Interpersonal Violence). Child, partner, or Elder maltreatment/neglect, are expressions of family/partner violence; whereas “youth violence; assault by strangers; violence related to property crimes; and violence in workplaces and other institutions” are forms of community violence (VPA, 2021, para. 4). Violence within 2SLGBTQ+ relationships is often stigmatized and ignored in heteronormative programming. Social, political, and economic violence such as social exclusion, structural racism, and epistemic racism (Reading, 2013) are examples of collective violence (VPA, 2021).

Figure 2

Typology of Interpersonal Violence

Religion or language once organized people into social class structures (Reading, 2013). However, colonization replaced religion and language rankings with race classifications misappropriated as a scientific measure for human characteristics. Racial classifications applied biological understandings to socially-constructed concepts that used scientific evidence to generate beliefs regarding intelligence, evolution, and violence. Relational racism is the day-to-day overt acts of violence that BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) and 2SLGBTQ+ people experience, such as being followed in a store, called names, or physically attacked because of skin colour or sexual/gender expression. Government acts and policies established covert forms of systemic racism, such as social exclusion. Social exclusion is an act of community violence (Raphael, 2020).

People are racialized through physical and/or social isolation policies resulting in unfair distribution of housing, healthcare, education, and employment (Jacklin & Warry, 2012). For example, 2SLGBTQ+ leaving violent relationships often encounter exclusion from shelters because they do not fit into the female heterosexual intimate partner violence survivor stereotype (Mortimer et al, 2019). Indigenous peoples in Canada experience social isolation through the rural and remote location of reserves, and at one time Indigenous peoples held no voting rights (Raphael, 2020). Many Indigenous communities experience poor quality of housing or infrastructure; access to clean drinking water may be an issue even within 50 kilometres of a town or city (Government of Canada, 2021).

Epistemic racism, preferring one form of cultural knowledge over another, often goes unacknowledged (Reading, 2013). Structural racism builds from epistemic racism believing that western knowledge systems are superior. Government deeds create inequitable laws, policies, rules, and regulations; these prevent opportunities to contribute to the economy, develop resources, and participate in political endeavours. Knowledge bias creates oppressive and discriminatory practices. The practices then become structural systems that support dominance for settlers’ perspectives and needs, without Indigenous peoples’ input. Examples include reserve size, health treatment options, and legal approaches and outcomes.

Reading (2013) explains that embodied racism is the somatic reaction to covert forms of racism. Indigenous peoples experience the many forms of racial violence that go unaddressed and over time create lingering trauma responses. Colonization changes the brain’s neural pathways and neurodecolonization must take place within the colonized person to generate helpful, empowering thoughts (Yellow Bird, 2013). Michael Yellow Bird, a social worker, developed neurodecolonization theory by converging Indigenous-healing and Western-based practices (Yellow Bird, 2013). Neurodecolonization theory is the process of reconciling the effects of colonization through mindfulness practice and then seeking united solutions to issues of well-being. Before reconciliation can take place, one must decolonize one’s mind and overcome negative feelings created by structural oppression (maintained through colonialism), by exercising neurodecolonization (Yellow Bird, 2013). Social workers can also decolonize their own minds by challenging power imbalances, incorporating a mindfulness practice, and countering the colonized mind by exposing forms of racism and racial structures.

Social workers who keep in their awareness that trauma impacts might be the result of violence, and that the interventions available are based on a western-dominant, colonized system, can then challenge the impulse to blame/judge the client’s actions as moral failings. Clients’ decisions or actions might be based on a trauma response that stemmed from one or more violent incidents/experiences with colonial and patriarchal structures. For example, children who witnessed intimate-partner violence between their caregivers may develop childhood-trauma symptoms such as heightened anxiety around others. The child may feel highly anxious when in the social worker’s presence and as a result might respond with defiance or hostility. Understanding that a child may feel unsafe in the presence of others will help to inform a social worker to create an environment that supports the child to feel safe and in control. If a teenager presents with self-harming behaviour (such as cutting), the social worker can hold in their awareness that incidents of sexual assault or abuse may increase the likelihood of self-harming behaviour (Madge et. al., 2011). Leading with a trauma-and-violence informed lens will support social workers in seeing the self-harming behaviour as a possible coping mechanism as opposed to attention-seeking performance. The act of immediately assuming negative stereotypes about Indigenous peoples may be explained by understanding that the first settlers generated negative stereotypes of Indigenous people as defiant, hostile, and attention-seeking and thus situated Indigenous peoples in the position of needing control and management. In contrast, trauma-and-violence informed care (TVIC) observes that client behaviour arises from disrupting or overwhelming experiences based in colonial messaging and structures, which in turn requires a safe, caring, non-judgmental environment.

To uncover covert violent practices of systemic racism, social workers can critically self-reflect upon their own colonial history, and/or position of privilege, and/or assimilation/oppressive practices. For example, clients who themselves have faced negative residential school experiences, or their family members, may unknowingly hold mistrust of government institutions in their physiological or psychological systems (Truth and Reconciliation Commission [TRC], 2012). It is important for all social workers to develop trauma-informed policies and practices, and attend training to mitigate potential harms to clients. Experiences of discrimination and other forms of violence are prominent amongst people who do not fit into the white, male, heterosexual, able-body, categories. Abuse based on gender or sexuality; or spiritual; emotional, financial, psychological or physical control negatively influences decisions and outcomes about well-being. Thus, to effectively practice trauma-and-violence informed care, it is important for social workers to contextualize their client’s behaviour, versus viewing it as a pathology or as a moral failing.

Universal Trauma Precautions

A social work trauma-and-violence informed care practice goal is to minimize harm to clients (Canadian Association of Social Workers [CASW], 2005; Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers [SASW], 2020). Embedding universal trauma-and-violence precautions into policies and approaches for work with all people helps to create a common delivery method for helpers to provide consistent services to lessen the potential to unintentionally re-traumatize the client. Broadening the definition of trauma supports social workers to understand trauma as “inextricably linked to systems of power and oppression” (Becker-Belease, 2017, pp. 131-132) versus understanding trauma as an “individual pathology.” Trauma-informed methods that question the “status quo” broaden a social worker’s approach to include the elimination of inequality and racism that cause harm/trauma. Trauma-and-violence informed care helps survivors to reclaim their power, by considering “client’s sensitivity to issues of trust, power, and stigma” (Becker-Belease, 2017, pp. 134-136). As follows, to mitigate potential barriers to care and better meet the unique needs of trauma-impacted people, rural/remote social workers should be encouraged to incorporate universal trauma-and-violence informed approaches.

Trauma-impacted people often feel terror, shame, helplessness, and powerlessness (Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse, 2014). To reduce negative experiences and increase safety and control, rural and remote social workers are invited to integrate universal trauma-and-violence precautions by assuming every person they work with may have experienced trauma and/or violence, and therefore do not have to retell their story and be potentially retraumatized. Social workers can lessen the potential triggers that occur in telling one’s story and in turn can increase the client’s sense of safety, self-determination, and resilience. Trauma-and-violence informed practice is a harm-reduction approach because the social worker minimizes potential negative experiences for people living with trauma. The outcome from using universal trauma precautions is a reduction in client blame and pathologizing of client behaviours, and is essential to reducing harm when working with rural and remote clients.

Examples

Critical Thinking Question #1

- You begin planning to work with your first client. How might you prepare to discuss incidents of trauma and violence with your client. What might prevent you from broaching the subject with your client? What experiences might they have encountered that are trauma and violence related? When would you ask for help if you encounter difficulties in working with your client about trauma and violence?

Mitigating Secondary Trauma

Secondary trauma results from providers listening to the troubling details of client trauma stories (Bishop & Schmidt, 2011; Harrison & Westwood, 2009; Hensel et al., 2015; O’Neill, 2010), and is also referred to as vicarious trauma or secondary traumatic stress (Elwood et al., 2011). Secondary traumatic stress is “the stress resulting from helping or wanting to help a traumatized or suffering person” (Figley, 1993a in Figley, 1995, p. 7); it has psychological characteristics resembling post-traumatic stress disorder (Baird & Kracen, 2006). Alternatively, vicarious trauma is the “harmful changes that occur in professionals’ view of themselves, others, and the world, as a result of exposure to the graphic and/or traumatic material of their clients” (Baird & Kracen, 2006, p. 181).

Social workers most impacted by secondary trauma are newer workers with high trauma caseloads, as well as a personal history of trauma and stressors outside of work (Dagan et al., 2015; Devilly et al., 2009). Social workers in remote locations in Canada reported that isolation and dual relationships/boundary challenges negatively impacted their well-being. They also conveyed limited access to clinical supervision, colleagues, and client supports led to poor mental health (O’Neill, 2010; Seidlikoski Yurach, 2021). Signs of experiencing secondary trauma are increased levels of arousal (hypervigilance), intrusion (negative thoughts/images), and avoidance (places/people) (Bride et al., 2004).

To lessen the impacts of secondary trauma on social workers, organizations acknowledge the implications of client trauma stories on rural and remote providers including how it might impede their ability to carry out daily activities (O’Neill, 2010). Secondary trauma is a valid concern for service providers and “the key to successfully working with trauma victims is understanding secondary trauma and the risks associated with hearing traumatic material and finding ways to process and cope with it” (Hesse, 2002, p. 308). Taking care of oneself is paramount in rural/remote social work practice. Therefore, social workers should also incorporate continuing education and professional development that includes trauma-and-violence informed theories and information about Canada’s colonial legacy as part of their practice. Doing so may help reduce incidents of secondary trauma and provide social workers with a clearer understanding of the trauma passed on to the population with whom they are working.

Trauma-informed practice includes taking care of the needs of practitioners and helpers. Benedict (2015, p. 18) comments that “…the healing journey and spirit of the helper is just as important as that of the one seeking help…” and “in order to help in a good way with a good mind, helpers need to be cared for and care for ourselves.” To incorporate a trauma-informed framework, the social worker must understand that they are participating in their own healing journey. Working with trauma-impacted people means the people providing the service are also tending to their own well-being in a holistic way (Wieman, 2009). For example, Somatic Experiencing® is a neurobiological approach to releasing traumatic shock from disrupting events. Peter Levine (2010) created this framework, as well as specific clinical tools, to support trauma healing. Some professionals working with trauma-impacted people feel they have limited control over their positions; thus, they might attempt to control others as a management strategy. Incorporating Somatic Experiencing® practices helps to regulate the social worker’s nervous system and in turn creates an environment of safety, self-determination, and resilience for the client. Somatic Experiencing® is an approach that is not taught within the social work practice. Social workers interested in using this approach may access the information through books or take specific training around the world through different venues. Continuing professional development such as workshops that focus on healing oneself is as important as social work practice-based information.

When participating in one’s own healing journey, Elder teachings inform us that for some, an Indigenous belief is that reciprocity is paramount in healing; in other words, we are all healing together (LaVallie, 2019). Institutions, particularly those in rural/remote locations, can create supportive healing work environments to mitigate/prevent secondary trauma for workers including: access to regular debriefings and clinical supervision, and open discussions amongst colleagues about the stressors of social work (in person or remotely) as an important daily/weekly routine. Although rural/remote and northern locations may have limited access to supports to lessen secondary trauma such as professional colleagues, interdisciplinary teams (Collins & Long, 2003) and/or “a community of practice” (Wenger & Snyder, 2000), these supports are readily available online or by phone. Working on their own healing journey within a supportive work environment can create a strong foundation for social workers to reduce and/or prevent the effects of secondary trauma.

This section identified the first strand of the braid: social workers approaching their clients with a universal trauma precaution lens. Social workers endeavor to assume that all clients may have experienced trauma that includes some form of violence encounter and thus lead with a non-judgmental approach. As well, following the principles of offering choice, a safe space (physically and psychologically), collaboration, and focusing on the client’s strengths, the social worker is the first intervention when employing trauma-and-violence informed care. The client may not feel like a whole person due to the trauma; therefore, resourcing the client’s strengths helps to lessen their trauma response. Remember that the social worker does not need to know the client’s whole story, only that an incident impacted the client and that they may display an unexpected response due to a physical or psychological trigger. All social workers may be at risk of experiencing secondary trauma. To prevent this negative impact, social workers should attend professional development opportunities regarding trauma-and-violence informed practice and opportunities that support healing one’s self. In addition, social workers must work to decolonize the institutions and organizations that continue to oppress and marginalize clients. To do this, they first decolonize their own minds through neurodecolonization methods and then endeavor to incorporate culturally suitable approaches. The next section explores how social workers can braid in decolonizing culturally suitable approaches to strengthen the human services they offer to clients.

Braid 2 Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework

Although, as discussed in the previous section, social-work professionals must be trauma-and-violence informed, questions can still arise regarding the cultural suitability of western-developed trauma-and-violence informed approaches “based on adherence to Westernized culture” (Knowlton & Lafavor, 2021, p. 1). Eighty-eight percent of practitioners surveyed, who work with American Indigenous trauma-impacted peoples, believed there was a “lack of inclusivity of culturally-informed approaches with current” evidence-based practices (Knowlton & Lafavor, 2021, p. 11). Evidence-based practice has “long been criticized for its ethnocentrism in which outcomes from empirical studies are thought to generalize across a wide range of populations” (Knowlton & Lafavor, 2021, p. 16). Ethnocentrism is the practice of comparing one’s own cultural standards and beliefs against another while holding in their awareness the superiority of their own culture. For example, western settler understandings of how things are done and what one should value took precedence over other ways of knowing. What was “proven” as scientific was really a narrow understanding of what was true for western-based people. Canada’s colonial legacy created a false belief that non-western-based science, ability, intellect, and cultural practices were unevolved and without merit. Leaders, at that time, set policies in place to treat Indigenous peoples and communities as inferior and as needing to be controlled (for example the Indian Act, the Indian Agent’s role, and the use of residential schools). Decolonizing is the process of examining colonial systems and then creating a new way of moving forward that honours the ways of knowing and being of the peoples who were colonized (Linklater, 2014).

Indigenous communities experience continued chaos due to “oppression, colonization, and residential school history” and the resulting stress is associated with “depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and difficulty expressing emotions” (Brave Heart, 2004 as cited in Linklater, 2011, p. 34). There are links between substance abuse and mental health issues stemming from traumatic memories resulting from failed assimilation processes (Health Canada, 2011). Indigenous-based teachings, activities, and practices include methods that are helpful for trauma-impacted people (LaVallie, 2019; Linklater, 2011; Sasakamoose et al., 2017). Cultural trauma-informed care “acknowledges and teaches about the Indigenous-specific effects of colonial policies and how they are linked to historic and current medical services for Indigenous people” (Indigenous Health Working Group, 2016, p. 5). Therefore, key approaches to address well-being must include understanding Canada’s colonial history, providing culturally-safe services, and valuing cultural knowledge (Health Canada, 2015). As such, social work services ought to consist of culturally-suitable and trauma-informed treatment and supports. The following section will explain how to employ culturally-suitable approaches by understanding cultural safety, using reflexivity in social work practice, and implementing an Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework. These three factors create the second braid in the trauma-and-violence informed, culturally-suitable, social work practice braid.

Cultural Safety

Rural and remote based social workers find it important to provide services that demonstrate cultural understanding, respect, and inclusion (CASW, 2005, p. 4). Those working with Indigenous people must be aware of their unique needs to provide culturally-safe services (Health Canada, 2015). Cultural safety encourages providers to recognize power imbalances and reflect on their biases that support discrimination. Discrimination is “Treating people unfavourably or holding negative or prejudicial attitudes based on discernable differences or stereotypes (AASW, 1999)” (as cited in CASW, 2005, p. 34). Cultural safety goes beyond refraining from “making assumptions based on people’s appearance or presumed ethnicity” (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 9), as it includes challenging power imbalances (unequal influence over self-determination or economy) and changing practice approaches. Cultural safety involves social workers acknowledging that service users decide “whether the professional relationship feels culturally safe” (De & Richardson, 2008, p. 39). Therefore, even if a social worker believes they are presenting in a culturally-safe way, if a service user indicates otherwise, social workers must be open to learning from the teachings/critique provided by the service user. Ultimately, cultural safety is the practice of supporting the client to express their culture.

Institutional barriers that inhibit Indigenous peoples from receiving culturally-safe care include limited understandings of Canada’s colonial history and assimilation policies, and a lack of respect for Indigenous ways of knowing and healing (First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Advisory committee of the Cultural Safety committee for the Cultural Safety Working Group [CSWG], 2013, p. 8). The CSWG (2013) states that “To be effective, care providers need to understand how the burden of unresolved personal and historical losses carried by many recipients of care may shape present behaviour” (p. 11). For people “who are attempting to work through other traumatic experiences, or who are dealing with severe psychological pain and addictions, understanding the dynamics and impact of history can be a part of the therapeutic healing process” (Aboriginal Healing Foundation [AHF], 2006, p. 42). Agencies and helping professionals are, therefore, encouraged to “participate in cultural competence and understanding as it relates to the Indigenous populations they serve” (Klinic Community Health Centre, 2013, p. 51). Failing to do so can potentially cause additional distress for individuals seeking supports.

The Canadian Association of Social Workers (CASW, 2005) adopted Guidelines for Ethical Practice outlining both cultural awareness and sensitivity. Through the guidelines, social workers are invited to understand culture, acknowledge diversity, respect the impact of their own heritage, and be aware of the customs and languages of their clients (CASW, 2005, p. 4). The Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers (SASW, 2020) expands the CASW (2005) guidelines, and asks for social workers to “strive to obtain a working knowledge and understanding of the impact that their own heritage, values, beliefs, and preferences can have on one’s practice and on clients whose background and values may be different from their own” (SASW, 2020, p. 11). To be compassionate, to build relationships, and to understand others, one must engage in a process of critical self-reflection to understand one’s self. To work in rural or remote communities, social workers must reflect on their positionality in colonial structures and take on a broader perspective based on openness and curiosity to another’s culture such as cultural humility (coined by Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). Cultural safety, therefore, needs to include cultural awareness, sensitivity, competence, and cultural humility.

Examples

Critical Thinking Activity #2

- A school located in a remote community hires you as the school’s liaison social worker. The principal asks you to increase parent attendance at parent teacher interviews. How would you braid together a trauma-and-violence informed approach with cultural responsiveness to complete this task? What information do you need to prepare the braids? Who would you enlist to support your work? Where would you start in creating relationships with the students, the school, the parents, and the community?

Reflexivity

A decolonizing, trauma-and-violence informed approach in social work practice involves a process of critical self-reflection to develop innovative approaches to healing (Linklater, 2011). Reaching out for help, by trauma-impacted people, depends on several factors including availability of services, perceived ‘victim blaming,’ and a lack of trauma-informed responses by practitioners (Schreiber et al., 2010). Reflexivity is a contemplative practice that invites social workers to explore their experiences, challenge their biases, and discover how they have changed because of the process (LaVallie, 2019). Schreiber et al. (2010) argue that “Public attitudes about interpersonal violence and mental health play an important part in shaping the social environment in which the [trauma-impacted people] and the help-providers are embedded” (para. 18). We need more trauma-and-violence informed and trained professionals, who are knowledgeable about agencies in order to refer clients and to incorporate a reflexive contemplation of the social worker’s role in supporting healing. Strategies produced by the social worker represent a combined way of knowing that is not returning to the “time before” but creating a new way forward (LaVallie, 2019). Employing trauma-and-violence informed measures means embracing local healing practices or approaches. Braiding cultural responsiveness and trauma-and-violence informed care frameworks into social work practice competencies relies heavily on institutions, which must honour and provide opportunities for Indigenous-based ways of healing. Only with institutional support will social workers be able to harmonize with clients so that culturally suitable and trauma-and-violence information care practices can be used. Most importantly, social workers and clients should feel free to employ culturally-suitable methods that match local customs and ways of healing.

Social workers employing Indigenous cultural responsiveness need to start by examining their own ethnocentrism. They do this by building a relationship with people who are “not like them.” Relationship building honours five elements: respect, reciprocity, relevance, responsibility, and reflexivity. Sasakamoose (as cited in Evans et al., 2020), when discussing research practices, states that “Kirkness and Barnhardt (1991) have identified the “4 Rs” for developing research procedures in an Indigenous context and Kovach (2010) identified a fifth” (p. 65), which is reflexivity. Reflexivity moves past simple reflection, and toward examining how the practitioner was changed because of the work done with the client, together in a relationship of a healing. To deepen the reflexivity process, the social worker uses cultural catalysts to invite relationships to develop with the client, community, environment, and ethos, which then support co-constructing new knowledge for healing (LaVallie, 2019). Cultural Catalysts and local healing practices are cultural activities, prayers, smudges, drumming, ceremonies, hand-building activities, languages, sweats, dances, stories, and land-based activities based on local knowledge and regional materials. To employ reflexivity, social workers are invited to acknowledge the relationship they have with the client and/or community, decolonize practice competencies and institutional policies to mitigate triggers and equalize power imbalances, and incorporate local figurative language and ways of knowing and doing.

People living with trauma will often use more general professional resources to connect to mental health services (Stokes et al., 2017), such as their family doctor, nurse, social worker, or teacher (Ansara & Hindin, 2010; Schreiber et al., 2010; Woodtli, 2000). Although many professional practice guidelines talk about cultural safety and trauma-and-violence informed (TVIC) care as incorporating historical and cultural understandings, they do not include examples. TVIC guidelines, therefore, can appear vague, without clear examples of how to implement the theory (Stokes et al., 2017). Often missing from the guidelines is a non-western perspective—a perspective whereby an Indigenous culture and ways of knowing are incorporated into the trauma-healing experience. As previously discussed, western settlers created education systems and health institutions based on western ways of knowing and doing. Non-western healing approaches were devalued and left out of trauma-and-violence treatment approaches based on racist notions of inferiority and superiority.

Colonial systems (including learning institutions) expect helping professionals to understand the populations that they work with, but do not always give professionals adequate culturally-responsive resources. Even helping professionals that are of the same culture as their clients might struggle to incorporate local customs and ways of knowing because institutional barriers prevent adapting suitable assessment and treatment approaches. Social work practice competencies must include a trauma-and-violence informed framework along with an Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework to develop an overall comprehensive approach to work effectively in rural and remote communities. Culturally-suitable approaches can be met by being culturally responsive. Therefore, the next section will explain how cultural responsiveness, developed through a grass roots effort, guides western institutions in providing culturally-suitable practice options.

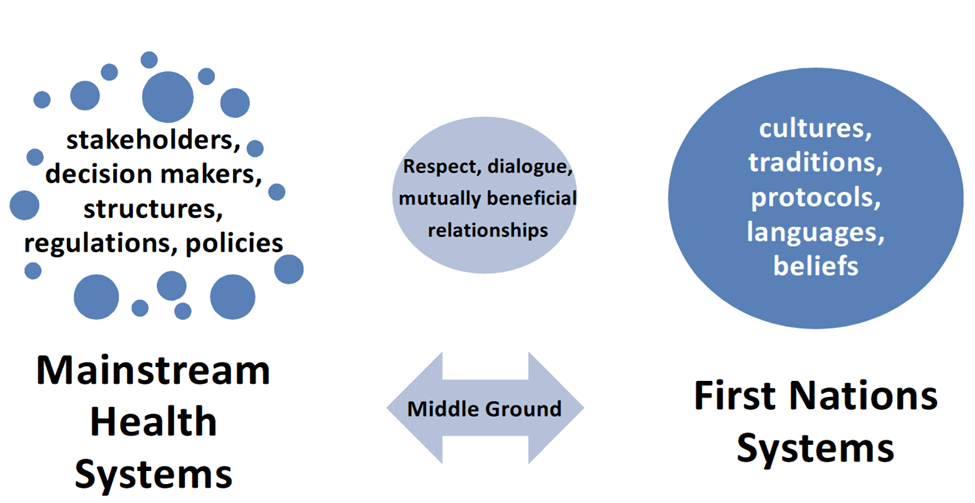

Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework

The Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework (ICRF; Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations [FSIN], 2013) is “about restoring and enhancing First Nations own health systems” (p. 7) whereby “the two systems could come together as equals to work together in a way that would be to the benefit of all” (p. 6; see figure 3), Thus, cultural responsiveness is a decolonizing approach to improve health and social-based systems by honouring Indigenous ways of knowing and being. The Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Theory “is a model created and owned by First Nations peoples living within Saskatchewan’s borders” (Sasakamoose et al., 2017, p. 1). This theory guides the Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework and provides principles that “can be locally adapted and applied” (Sasakamoose et al., 2017, p. 1) to communities servicing First Nations people. Principles in decolonizing approaches must be trauma-informed, strengths-based, community-engaged, and spiritually-grounded (Snowshoe & Starblanket, 2016). Cultural Responsiveness positions Indigenous systems alongside Western-based systems with a middle ground containing ethical space (Ermine, 2007), two-eyed seeing (coined by Marshall et al., 2015), and harmonizing ways of knowing (LaVallie & Sasakamoose, 2016). Ethical space is created and considered sacred (Sasakamoose et al., 2017). Within this middle ground, social workers interact with rural and remote populations to create culturally-suitable care and approaches. Employing Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework engages many of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s (TRC, 2015) calls to action. As part of this process, non-Indigenous partners and allies are encouraged to examine their values, skills, and attitudes about cultural competence and work toward reconciliation.

Figure 3

Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework

The second braid in the trauma-and-violence informed, culturally-suitable, social work practice braid recognizes power imbalances and asks the social worker to reflect on their own biases that support discrimination. This section explained how to employ culturally-suitable approaches by understanding cultural safety, using reflexivity in social work practice, and implementing an Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework. The social worker incorporates cultural awareness, sensitivity, competence, humility, and safety to provide a culturally-competent practice. Additionally, social workers are invited to reflect on their experiences with the clients. This reflection includes providing trauma-and-violence informed care, challenging discriminating thinking, and discovering how they and their practice have changed because of the process. The first two braids offered theory to inform practice. The next section introduces the third braid that weaves social work practice competencies with the theories.

Braid 3 Practice Competencies

Incorporating trauma-and-violence informed care (TVIC) while acknowledging the negative effects of a colonial legacy, providing culturally-safe services, and valuing cultural understandings works to dismantle ethnocentrism and covert racism. Social workers are invited to decolonize their approaches with rural and remote peoples by braiding frameworks that honour the lived experiences of trauma-impacted Indigenous persons. Braiding frameworks creates a stronger approach than using one strand alone. Social workers are encouraged to employ trauma-and-violence informed universal precautions to mitigate triggers by creating a safe space, starting their own healing journey, and employing Indigenous cultural responsiveness into services. This section offers practical applications to rural/remote social work competencies through the micro-level that involves working directly with individuals or families.

Creating Safe Space at the Micro-level

Social workers have a duty to provide trauma-and-violence informed care (TVI); this means prioritizing safety, control, and choice. Social workers braid a TVI framework strand and an Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework (ICRF) strand by learning about these two theories. They then begin to braid in the third strand of practice competency by starting their own healing journey and creating a safe space.

A safe physical and communicative space supports clients to share their experiences (Moss et al., 2012). To create a safe space, a social worker follows local customs to attain the services of, and collaborate with, an Indigenous or local Knowledge Keeper within the community the social worker offers services. Together they consider what would make the space feel comfortable and inviting for that community’s members. This resource person can guide the social worker in understanding what the client might need prior to the appointment. They can assist with information about barriers to parking, transportation, daycare, family obligations, or employment restrictions related to attending. Thus, creating a safe space starts with reducing barriers for clients to attend the appointment. The social worker then does a walk-through, with the Knowledge Keeper, starting with entering the building, going to the office or room, running through a mock session, and then leaving the location. The Knowledge Keeper will offer suggestions for visual identifiers and spaces that encourage safety, control, and choice. Local artwork, local language speakers, and access to food, beverages, and bathroom facilities (some clients may not have eaten before attending the appointment or had a long way to travel) encourage a sense of connection and acknowledgement of the client’s worldview. Walking through the space and employing universal trauma-and-violence protocols with Indigenous Cultural Responsiveness Framework will help to lessen trauma-inducing incidents. Social workers can also apply this approach to non-Indigenous peoples in rural and remote areas by enlisting the services of a local community member to aid with the walk-through, identify barriers to attending and ways to create a safe space.

Examples

Critical Thinking Activity #3

- Imagine that you are entering a building that you have not been in before. Notice how you feel before you open the door. What might you want to know before entering? Whom are you meeting, where are they located, is there a waiting room with other people? Are you able to walk right in or do you need someone to let you in? These are common questions that most people have before entering a new place. Now imagine if the place that you are going into is designed in a way that makes you feel unsafe. How does this affect the way you are feeling? Do you still want to enter the building? Should places be designed to make you ‘feel safe’?

Assessment

Trauma-impacted people endure memories, sensations, emotions, and/or images connected to the dysregulating event that impacts their ability to make a connection with others or to respond suitably. Social workers can hold in their awareness that, for some clients, making it to the appointment takes a lot of effort. Social worker interactions with trauma-impacted people may inadvertently re-traumatize or trigger the client through touch, innuendoes, interpretation of behaviours, and/or forceful or demanding language (Government of Canada, 2018). Approaching a person from behind or touching a person without permission (even on the shoulder) may activate an autonomic nervous response. The person may startle or lash out for seemingly no reason. A non-judgmental attitude invites the client to share their concerns about, or barriers to, attending the appointment.

Social workers use empathy, respect, immediacy, genuineness, conciseness, clarity, listening, and non-verbal behaviours to communicate (Beesley et al., 2018). However, they often overlook their own language when they think about working with clients. One’s intention behind communication is evident in how and what one says. Clients can interpret underlying biases, judgements, and assumptions held by the helping professional, which may result in the client feeling unsafe.

Trauma-and-violence informed assessments lessens triggering language, supports self-determination, and focuses on strengths. Social workers may regularly be conducting intake assessments and/or collecting statistical data on their clients. Many assessments and data collection forms use direct westernized language that may imply victim blaming, and/or trigger sensations from traumatic memories. The potentially negative experience may be further compounded by how the social worker asks the questions. Using universal trauma-and-violence precautions means that it may be important to re-word intake forms to lessen triggering language, and that it might be helpful to spread the intake assessment over two to three appointments. In addition, the social worker should focus on how the client was successful with decisions they made and how they can find self-determination.

Western-based intakes and intervention frameworks that focus on deficit and disease-based explanations are ineffective. Instead of asking a client where they have failed in controlling their depression, the trauma-and-violence informed care social worker may instead ask the client about when they have felt joy and happiness. Notice the difference in the questioning. After identifying strengths, the social worker then invites discussion about what supports the client needs or what barriers the client is facing. People seeking supports may begin to feel that the assessment process is meant to find blame and label them. Braiding cultural responsiveness into the assessment process can include holding a focus group with clients (with informed consent) and Knowledge Keepers to discuss the assessment process and intake documents, and to assist social workers to review their assumptions through a critical lens; thus, the social worker may be prepared to inform clients more effectively about the purpose of the support/intervention offered.

Employing Cultural Suitability When Working with Clients

Culturally-suitable, trauma-and-violence informed care includes the following: the social worker’s level of confidence in providing such care, use of and competence in culturally-informed treatment programming, support for culturally-responsive healing options, and referrals to suitable community-based resources. To employ culturally-suitable and trauma-and-violence informed care (TVIC), social workers may start by seeking to understand how colonial trauma has, and continues to influence the neurological functioning of both the social worker and the client. As discussed earlier in this chapter, structural racism is embedded in governmental institutions where many social workers work. The practice of neurodecolonization works to correct cognitive biases and current western mindlessness created by colonization (Yellow Bird, 2013). Social workers who are on their own healing journeys are invited to use neurodecolonization and encourage clients to implement the same contemplative-based practice to support positive, healthy neural networks for themselves (Yellow Bird, 2013). One-on-one interactions must take into consideration the importance of creating a safe space, mitigating triggering language, supporting self-determination, focusing on strengths, and practicing neurodecolonization.

Screening for Trauma

People have an autonomic nervous system that regulates the body’s functions. Heart rate, breathing, temperature, and digestion fluctuate throughout the day in response to many situations. Disruptive experiences initiate the fight, flight, or freeze response (autonomic system) to help people to become aware, protect, or defend themselves, and then return to normal. Trauma interrupts one’s natural orienting and protecting responses resulting in fixated physiological (Levine, 2010) and psychological states. Peter Levine developed the Somatic Experiencing ® theory, which was discussed earlier in this chapter, to work through the immobility (freeze) phase and complete the impaired survival response (fight or flight):

If the immobility phase doesn’t complete, then that charge stays trapped, and, from the body’s perspective, it is still under threat. The Somatic Experiencing® method works to release this stored energy, and turn off this threat alarm that causes severe dysregulation and dissociation. (Somatic Experiencing® International, 2021, para. 5)

It is important for social workers to screen for trauma experiences by holding in their awareness theoretical frameworks about the effects of colonization, the establishment of systemic racism, and the physiological and psychological responses to trauma and violence. Through this awareness, they create an environment for the client to share what supports and resources they need without forcing them to relive their trauma story. Social workers can “acknowledge the root causes of trauma without probing” (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 10). To do this they should express concern, listen without judgement, and recognize the client’s strengths.

Delivery and Intervention

Being trauma-and-violence informed involves having cultural competence regarding the traditions and practices of any specific culture. When working with rural and remote peoples, an understanding of their cultural practices is essential in promoting and supporting the healing process. Traditional healing practices are localized and culturally specific (Klinic Community Health Centre, 2013). Social workers employing culturally-responsive trauma-and-violence informed care will invite local Knowledge Keepers and clients to inform them and the organization about what should be included in delivering general care and intervening in situations. It is therefore important to be curious about the culture of your client and avoid inaccurate assumptions. Paramount to trauma-and-violence informed care is that the client has a choice over their support and should always be referred to the most appropriate agencies for a full complement of services. An example of this is the work done through the Regina, Saskatchewan based Wellness Wheel. Established in 2016, this agency works to provide enhanced and equitable access to care, by true engagement in the community to inform front-line services (Wellness Wheel, 2016). Local Knowledge Keepers, peer advocates, and users engage in discussion with front-line service workers to braid Indigenous culturally-responsive treatment options into care for people living with HIV/AIDS and other chronic conditions.

Counselling, Consultation, and Programming

Social workers value clients’ right to self-determination or control in decisions about their overall well-being (CASW, 2005). Self-determination is the ability to hold control over one’s choices or the community in which they interact. It is assumed that trauma-impacted people had control taken from them; therefore, the social worker’s role is to provide a trauma-informed process that reintegrates control into the client’s decision-making processes and physiological awareness. Clients often feel a lack of voice within systems that perpetuate victim-blaming, or ignore the effects of colonization, and preserve systemic racism. Social workers willing to build a strong understanding of how colonization and intergenerational trauma has impacted Indigenous peoples’ well-being, and in turn support the client and community self-determination (Reading & Wien, 2013), will reduce barriers and misunderstanding.

Mezzo and Macro Levels

The social work practice area at the mezzo-level includes working with groups and organizations (schools, businesses, neighbourhoods, hospitals, non-profits, and small-scale communities), in rural and remote areas. Cultural-responsiveness and trauma-and-violence informed concepts braided into social work practice competencies focuses on accessibility, advocacy, and administration. Accessibility, availability, and adaptability of services, directly and indirectly, affect Indigenous service-users’ well-being (National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health [NCCIH], 2019). Rural and remote service areas experience barriers to care stemming from “colonialism, geography, health systems, health human resources, jurisdictional issues, communications, cultural safety, and traditional medicines” (NCCIH, pp. 1-2). People living outside of urban areas experience inequitable access to care. For example, the Indian Act directed Indigenous peoples to live in rural and remote locations thus creating issues with recruiting and retaining service providers. Rural and northern communities find it difficult to fill social work positions and keep workers, long term. As well, jurisdictional issues relating to service coverage prevents clients from accessing available and culturally-suitable services promptly.

Social workers at the macro-level work with large-scale systems (laws, government policies, funds, activist groups, social policy) in rural and remote areas. Advocacy is an expected role of social workers (CASW, 2020). Social workers seek “to improve systems and to address structural or systemic inequalities” and work to implement “Strategies that include members of a community in conversations and actions” (CASW, 2020, p. 4). An example of providing advocacy through a trauma-and-violence informed, culturally-responsive practice framework could be to provide support to 2SLGBTQ+ persons seeking transition or crisis housing in rural or remote locations. It is true that across Canada, self-identified women in general face higher incidents of intimate-partner violence (Public Safety Canada, 2021). Programs usually assume that relationships are heterosexual; and therefore, often exclude or discriminate against lesbian or bi-sexual relationships. Further marginalized individuals are two-spirited people, men, transgendered, queer, or non-binary survivors because they do not fit into the gendered norm of heterosexual women survivors of intimate partner violence. Holding local focus groups with 2SLGBTQ+ community members to determine their unique needs along with culturally suitable responses and treatment approaches can inform social workers about where and how to advocate for their clients in rural and remote locations where services are limited. Solutions to accessing services may include, not having to explain experiences of abuse or sexual orientation, and housing transgendered people in smaller groups to improve feelings of safety and control. A decolonial culturally appropriate approach includes getting to know the 2SLGBTQ+ community to strengthen relationships and trust, especially for client’s requiring transitional or crisis housing. Social work as a profession includes working for changes in policies and systems knowing the specific needs of the community that they are representing. They in turn with communities can inform the police, law-makers, and the public on how to reduce harm and mitigate trauma-and-violence experiences.

Conclusion

This chapter offered a discussion and exploration of a braided framework as a foundation to begin developing the social worker’s competencies for work with rural and remotely located Indigenous clients by increasing safe and suitable accessibility of services and ensuring appropriate and timely referrals. Working with trauma impacted clients means acknowledging that they may have experienced, or continue to experience, violence. The goal for social work practice in these communities with these populations is to mitigate triggering experiences and reduce harming incidents. This chapter invited the social worker to identify power imbalances in rural, remote, and northern practice. The sections wove the principles of trauma-and-violence informed care and the Indigenous Cultural-Responsiveness Framework along with practice competencies. With this information, social workers should be able to begin aligning social work competencies with universal trauma precautions. Braiding in culturally-suitable perspectives and healing approaches strengthens client care efficacy. Creating relationships and reducing triggering language creates space for honest well-being related sharing. Braiding in is about exploring respectful approaches that support healing. Moreover, organizations can work to provide ample time and resources to create space for meaningful engagement.

[1] Concept used to describe a collective way of beliefs and values imposed upon Indigenous peoples by European-centric settlers, who enforced a Christian and positivistic viewpoint.

Additional Resources

- Briggs, P. C., Hayes, S., & Changaris, M. (2018). Somatic experiencing® informed therapeutic group for the care and treatment of biopsychosocial effects upon a gender diverse identity. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9.

- Government of Canada. (2018). Trauma and violence-informed approaches to policy and practice. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/health-risks-safety/trauma-violence-informed-approaches-policy-practice.html

- Sasakamoose, J., Bellegarde, T., Sutherland, W., Pete, S., & McNabb, K. (2017). Miyo-pimatisiwin developing Indigenous cultural responsive theory (ICRT): Improving Indigenous health and well-being. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(4).

References

Aboriginal Healing Foundation. (2006). Final report of the Aboriginal healing foundation. Volume III: Promising healing practices in Aboriginal communities. http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/final-report-vol-3.pdf

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

Ansara, D., & Hindin, M. (2010). Formal and informal help-seeking associated with women’s and men’s experience of intimate partner violence in Canada. Social science & medicine, 70.

Baird, K., & Kracen, A. C. (2006). Vicarious traumatization and secondary traumatic stress: A research synthesis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 19(2), 181-188.

Becker-Blease, K. (2017). As a world becomes trauma-informed, work to do. Journal or Trauma & Dissociation, 18 (2), 131-138.

Beesley, P., Watts, M., & Harrison, M. (2018). Developing your communication skills in social work. Sage Publications Ltd.

Benedict, A.K. (2015). Dying to get away: Suicide among First Nations, Metis and Inuit Peoples. In K. Kandhai (Ed.), Inviting Hope. Aboriginal Issues Press.

Bishop, S., & Schmidt, G. (2011). Vicarious traumatization and transition house workers in remote, northern British Columbia communities. Rural Society, 21(1), 65-73.

Bride, B., Robinson, M., Yegidis, B., & Figley, C. (2004). Development and validation of the secondary traumatic stress scale. Research on Social Work Practice, 14, (1), 27-35.

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2005). Guidelines for ethical practice 2005. https://www.casw-acts.ca/en/what-social-work/casw-code-ethics/guideline-ethical-practice

Canadian Association of Social Workers. (2020). CASW scope of practice statement. https://www.casw-acts.ca/en/casw-scope-practice-statement

Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse. (2014). Trauma-informed care. The essentials of…series. https://www.ccsa.ca/sites/default/files/2019-04/CCSA-Trauma-informed-Care-Toolkit-2014-en.pdf

Collins, S., & Long, A. (2003). Too tired to care? The psychological effects of working with trauma. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10(1), 17-27.

Cultural Safety Working Group, First Nation, Inuit and Métis Advisory Committee of the Mental Health Commission of Canada (CSWG). (2013). Holding hope in our hearts: Relational practice and ethical engagement in mental health and addictions [Final Report].

De, D., & Richardson, J. (2008). Cultural safety: an introduction. Nursing Children and Young People, 20(2), 39-44.

Dagan, K., Itzhaky, H., & Ben-Porat, A. (2015). Therapists working with trauma victims: The contribution of personal, environmental, and professional-organizational resources to secondary traumatization. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 16(5), 592-606.

Devilly, G. J., Wright, R., & Varker, T. (2009). Vicarious trauma, secondary traumatic stress or simply burnout? Effect of trauma therapy on mental health professionals. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 43(4), 373.

Elwood, L. S., Mott, J., Lohr, J. M., & Galovski, T. E. (2011). Secondary trauma symptoms in clinicians: A critical review of the construct, specificity, and implications for trauma-focused treatment. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 25-36.

Ermine, W. (2007). The ethical space of engagement. Indigenous Law Journal, 6(1).

Evans, J., Bremner, L., Johnston, A., Rowe, G., & Sasakamoose, J. (2020). Guiding Principles and Considerations from Indigenous Approaches to Evaluation and Research. Department of Justice, Canada.

Federation of Saskatchewan Indian Nations. (2013). Cultural responsiveness framework. https://allnationshope.ca/userdata/files/187/CRF%20-%20Final%20Copy.pdf

Figley, C. (1995). Compassion fatigue as secondary traumatic stress disorder: An overview. In C. Figley (Ed.), Compassion fatigue: Coping with secondary traumatic stress disorder in those who treat the traumatized (1-20). Routledge.

Government of Canada. (2018). Trauma and violence-informed approaches to policy and practice. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/health-risks-safety/trauma-violence-informed-approaches-policy-practice.html

Government of Canada. (2021, May 21). Map of long-term drinking water advisories on public systems on reserves. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1620925418298/1620925434679

Harrison, R. L., & Westwood, M. J. (2009). Preventing vicarious traumatization of mental health therapists: Identifying protective practices. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 46(2), 203-219.

Health Canada. (2011). Honouring our strengths: A renewed framework to address substance use issues among First Nations People in Canada. http://nnadaprenewal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/Honouring-Our-Strengths-2011_Eng1.pdf

Health Canada. (2015). First Nations mental wellness continuum framework. https://thunderbirdpf.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/24-14-1273-FN-Mental-Wellness-Framework-EN05_low.pdf

Hensel, J. M., Ruiz, C., Finney, C., & Dewa, C. S. (2015). Meta‐Analysis of risk factors for secondary traumatic stress in therapeutic work with trauma victims. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(2), 83-91.

Hesse, A. (2002). Secondary trauma: How working with trauma survivors affects therapists. Clinical Social Work Journal, 30(3), 293-309.

Indigenous Health Working Group. (2016). Health and Health Care Implications of Systemic Racism on Indigenous Peoples in Canada. [report].

Jacklin, K., & Warry, W. (2012). Decolonizing First Nations health. In J. Kulig, & A. Williams, (Eds.), Health in rural Canada (pp. 373-389). UBC Press.

Klinic Community Health Centre. (2013). Trauma informed: The trauma toolkit (2nd ed.).

Knowlton, C., & Lafavor, T. (2021). Attitudes toward evidence-based practices for trauma-impacted American Indian/Alaska Native populations: Does the role of culture even matter?. Journal of Indigenous Research, 9(2).

LaVallie, C. (2019). Onisitootumowin Kehte-ayak (the understanding of the old ones) of healing from addiction [Doctoral dissertation, University of Regina]. OURspace.

LaVallie, C., & Sasakamoose, J. (2016, June 22–24). Healing from addictions through the voices of Elders [Panel]. Traditional Knowledge and Research, First Nations University of Canada.

Levine, P. (2010). In an unspoken voice. North Atlantic Books.

Linklater, R. B. L. (2011). Decolonising trauma work: Indigenous practitioners share stories and strategies [Doctoral dissertation, University of Toronto]. Proquest Dissertation Publishing.

Linklater, R. A. (2014). Decolonizing trauma work: Indigenous stories and strategies. Fernwood Publishing.

Madge, N., Hawton, K., McMahon, E., Corcoran, P., De Leo, D., de Wilde, E., Fekete, S., van Heeringen, K., Ystgaard, M., & Arensman, E. (2011). Psychological characteristics, stressful life events and deliberate self-harm: Findings from the Child & Adolescent Self-harm in Europe (CASE) Study. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 20(10), 499–508.

Marshall, M., Marshall, A., & Bartlett, C. (2015). Two-eyed seeing in medicine. In M. Greenwood, S. de Leeuw, N. M. Lindsay, & C. Reading’s (Eds.), Determinants of Indigenous peoples’ health in Canada: Beyond the social (16-24). Canadian Scholars’ Press.

Mortimer, S., Powell, A., & Sandy, L. (2019) ‘Typical scripts’ and their silences: exploring myths about sexual violence and LGBTQ people from the perspectives of support workers. Criminal Justice, 31(3), 333-348.

Moss, A., Racer, F., Jeffery, B., Hamilton, C., Burles, M., & Annis, R. (2012). Transcending boundaries: Collaborating to improve access to health services in northern Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In J. Kulig & A. Williams(Eds), Health in rural Canada (pp.159-177). UBC Press.

National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health. (2019). Access to health services as a social determinant of First Nations, Inuit and Métis health. https://www.nccih.ca/docs/determinants/FS-AccessHealthServicesSDOH-2019-EN.pdf

O’Neill, L. K. (2010). Northern helping practitioners and the phenomenon of secondary trauma. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 44(1), 130-149.

Public Safety Canada. (2021, March 4). Government of Canada legislation targets intimate-partner violence [news release]. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-safety-canada/news/2021/03/government-of-canada-legislation-targets-intimate-partner-violence.html

Raphael, D. (2020). Poverty in Canada: Implications for health and quality of life (3rd. ed.). Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.

Reading, C. (2013). Understanding Racism. The National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. http://www.nccah-ccnsa.ca/419/Aboriginal_Racism_in_Canada.nccah

Reading, C., & Wien, F. (2013). Health inequalities and social determinants of Aboriginal peoples’ health. National Collaborating Centre for Aboriginal Health. https://www.nccih.ca/495/Health_inequalities_and_the_social_determinants_of_Aboriginal_peoples__health_.nccah?id=46

Restoule, B. (2015). Conducting assessments in First Nations and Inuit communities: A training and reference guide for front line workers. Thunderbird Partnership Foundation.

Sasakamoose, J., Bellegarde, T., Sutherland, W., Pete, S., & McNabb, K. (2017). Miyo-pimatisiwin developing Indigenous Cultural Responsive Theory (ICRT): Improving Indigenous health and well-being. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 8(4).

Saskatchewan Association of Social Workers. (2020). Standards for practice for registered social workers in Saskatchewan. https://sasw.ca/site/standardsofpractice

Schreiber, V., Maercker, A., & Renneberg, B. (2010). Social influences on mental health help-seeking after interpersonal traumatization: A qualitative analysis. BMC Public Health, 10(634).

Seidlikoski Yurach, W. (2021). The power of stories: The experiences and well-being of mental health providers working in northern Saskatchewan communities. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Saskatchewan]. Harvest.

Snowshoe, A., & Starblanket, N. (2016). Eyininiw Mistatimwak: The role of the Lac La Croix Indigenous pony for First Nations youth mental wellness. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing Te Mauri–Pimatisiwin, 1(2), 60–76.

Somatic Experiencing® International. (2021). About us. https://traumahealing.org/about-us/

Stokes, Y., Jacob, J., Gifford, W., Squires, J., & Vandyk, A. (2017). Exploring nurses’ knowledge and experiences related to trauma-informed care. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 4(1).

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf

Tervalon, M., & Murray-Garcia, J. (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: a critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Undeserved, 9(2), 117-125.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2012). They came for the children: Canada, Aboriginal peoples, and residential schools.

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2015). Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to action. http://www.trc.ca/websites/trcinstitution/File/2015/Findings/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf

Wellness Wheel. (2016). The need: Challenges of the current system to meet Indigenous health needs.

Wenger, E., & Snyder, W. (2000). Communities of practice: The organizational frontier. Harvard Business Review, 78, 139-145.

Wieman, C. (2009). Six Nations mental health services: A model of care for Aboriginal communities. In L. Kirmayer and G. Valaskakis (Eds.), Healing traditions: the mental health of Aboriginal people in Canada (401-418). UBC Press.

Woodtli, M. A. (2000). Domestic violence and nursing curriculum: Tuning in and tuning up. Journal of Nursing Education; 39(4), 173-182.

World Health Organization Violence Prevention Alliance. (2021). Definition and typology of violence. Retrieved March 30, 2021, from https://www.who.int/violenceprevention/approach/definition/en/

Yellow Bird, M. (2013). Neurodecolonization: Applying mindfulness research to decolonizing social work. In M. Gray, J. Coates, M. Yellow Bird, & T. Hetherington (Eds.). Decolonizing social work (pp. 293-310). Ashgate Publishing Company.

a way of being that reflects a caring, ethically-based relationship, recognizing “the connection between violence, trauma, negative health outcomes and behaviours” (Government of Canada, 2018, p. 2)

Evidence-informed methods and interventions that include the impact of trauma and violence on one’s life while targeting specific physical, mental, and spiritual health issues seen as overall well-being.

Unsettling physical or psychological experiences

the lingering memory, either psychologically or physiologically (or both), of a disruptive event that impacts a person’s sense of safety and control; and is defined as “a single event, multiple events, or a set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically and emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s physical, social, emotional, or spiritual wellbeing” (SAMHSA, 2014, p. 4).

the intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment, or deprivation” (VPA, 2021, para. 2).

Taking care of the needs of practitioners and helpers.