4 An Analytical Review of Pierre Trudeau’s Speeches from the Throne: Becoming Prime Minister in 1968 and 1980

Dayle Steffen

Introduction

The nature of Canada’s national identity is a progressively changing ideal that shifts across time, and this is never made clearer than through the speech from the Throne. Each version is written under the watchful eye of the Prime Minister and read by the Governor General to open a new session of parliament.1 The idea speech delivers a set of goals the government hopes to achieve, and charts the direction for the country. The Speech is focused on what the government holds as its central values and key con0cerns to better the nation. In short, the Speech from the Throne outlines what the new government plans to do to improve the country and what key aspects of identity on which it chooses to focus. What is interesting about an investigation of the Throne Speech is how the sense of what makes up Canada’s “national identity” almost always changes in some way or another under each new Prime Minister, as they outline what they believe Canada stands for as a nation, both domestically and internationally, and what its people should identify as.

One of the most significant of these changes occurred under Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau, as he placed such emphasis on social liberties and equality. His emphasis on those values had an incredible impact on Canada’s people in so many ways. Yet Prime Minister Trudeau’s Speeches from the Throne contained more than just this declaration; in fact, his vision for the country was so encompassing that his Speeches from the Throne were more like a point-by-point plan on what he hoped his government would accomplish, rather than presenting a more generalized vision for the country. It is not possible in a single chapter to consider all of Trudeau’s Speeches from the Throne that cover his 16 years in office. Rather, this paper examines what the vision for the country was when he first took office in 1968, and again when he was re-elected to office in 1980, comparing how these Speeches from the Throne were similar and different, and provides a snapshot his vision for Canada, and how it evolved over his time as Prime Minister.

Background

Pierre Trudeau was born on October 18, 1919 to a family of comfortable means and security, who would later become wealthy due to his father’s savvy business skills.2 This enabled young Trudeau, when he grew up, to attend prestigious educational institutions, such as l’Universitie de Montreal, and Harvard University, where he attained his doctorate in law after writing his dissertation on the relationship between Marxism and Christianity.3 He later became a professor of law at l’Universitie de Montreal, and concerned himself with the status of French speaking people in Canadian society.4 Of note, Trudeau also engaged in anti-conscription protests during World War II from 1942-44, referring to the war as “an exercise in British colonialism and imperialism” in which he felt that the French people in particular would pay dearly.5 Even from this early age, Trudeau demonstrated his loyalty to the French Canadian populace, but also to his ideals of non-violence and restraint from becoming involved in what he thought of as unnecessary international conflicts This would later play a significant role with the direction in which he drove the country as Prime Minister.

Moving into office in 1968, Trudeau was met with a country that was in the throes of social reform and unrest. Movements such as Quebec’s FLQ and the Red Power were demanding immediate federal and provincial action to grant liberties to the marginalized groups they represented, and to introduce reparative legislation for long-term sustainability.6 Additionally, the post-WWII economic boom had begun to decline as industrialization slowed and inflation began to rise, causing financial strain across the Western world.7

Unfortunately, these same concerns continued throughout the 1970’s, becoming even more pronounced, so that in 1980 when Trudeau was re-elected to office8, the situation in the country was reaching a breaking point. On the social side, English-French relations were at an all-time low and culminated in the Quebec Referendum of 1980.9 In the West, a rising feeling of being alienated by the federal government resulted in the beginnings of the new Western separatist movement.10 Additionally, the economic situation was also very bleak, and Canada was facing a serious recession due to a stale economy and lack of a diversified workforce.11 Indeed, at a glance, the climate in Canada from 1968 to 1980 had only changed in terms of its severity, but not its nature.

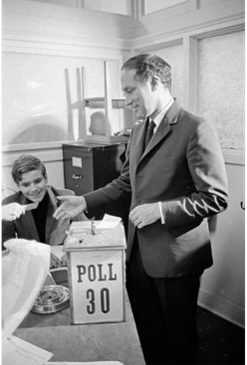

Speech of the Throne, 196812

This first Throne Speech of the new Trudeau Administration, delivered on September 12, 1968, was delivered by the Governor General, the Right Honorable Daniel Roland Michener for the opening of the 28th session of Parliament.13 Right away upon its opening words, the speech directed its attention towards the concerns of the Canadian people as a whole and addressed the need for the new government to connect more closely and openly with the people it governs. As one way of achieving this objective, it promised to ask Parliament to dispense with old and cumbersome procedures in the House of Commons and adopt more expedient policies that could work towards the changes that Canadians wanted and that were needed in a progressively modern society.14

The Speech then ambitiously addresses the idea of creating a unified Canada that would build greater cohesion with all of its people across the nation. One of the ways it hoped would build national unity was through a new Official Languages Act based on the recommendation of the Royal Commission of Bilingualism and Biculturalism. Trudeau believed that would then build increased equality and representation of both English and French as Canada’s official languages; better and strengthen attachment to all languages across the nation. He also promised better and fairer treatment to Status “Indians” (First Nations and Indigenous people), increased funding for transportation systems, educational programs, public television, and postal services.15 The rationale for such initiatives, as was explained, was simple: to create a constitution and government that protected the unity of all Canadians. At the same time, Trudeau announced in the Throne Speech that the federal government was in talks with the provinces to create a new constitution. The 1968 Throne Speech, particularly its short-term objectives, were designed to address immediate need while the constitution was being designed and patriated, or so the tone of the speech implies. The overall theme of the Speech was one of “righting of wrongs” in terms of creating a more just and equal Canadian society that reflects the values of humanitarianism and fairness.16 Its central objective was to afford all Canadians, the opportunity to have equal and easy access to economic opportunity and material gains, to develop new departments and initiatives to combat poverty, and to give proper recognition and representation to those groups that had been marginalized and “know what it is to feel injustice.”17 Within such a framework, there was a recognition that poverty cannot be immediately eliminated and that it was an ongoing process, just as fighting inequality. Yet Trudeau believed that if governments continue to be committed to these causes, then real societal change would occur. To this end, a promise was made to increase pensions for seniors, to create better programs for the sick and infirm, and to create a new department to provide better supports for economic opportunities to all Canadians.18

The Throne Speech also addressed Canada’s economic standing in the world. It proposed changes to the Criminal Code so that fairer justice be given to workers in terms of labor laws and disputes. The Speech discussed with great emphasis the need to create a competitive and self-sufficient Canadian economy that could stand up against “more advanced nations in the world”.19 Trudeau believed that to combat poverty, create diverse employment opportunity, and support Canadians’ desire for an increasingly material and comfortable lifestyle, the economy needed to change and grow. This section of the speech is interesting in that it is one of the few times international concerns were really discussed in any detail, and yet even within this, the larger focus is still placed on the immediate impact to Canadians, with internationalism only a by-product. For instance, the idea of helping to stabilize the world’s unsteady economics is discussed, and it was suggested that Canada needed to engage in more free and open trade with its partners around the world, yet the central point remained focused on reducing taxation and inflation for Canadians at home.20

The Speech does briefly discuss international concerns. Again, the idea of identity and national unity comes up in the proposal that policies be enacted to support conservation efforts both in terms of the natural environment and resources of the country, and also in terms of national parks and heritage sites. The idea here is to protect physical markers of the Canadian identity to be enjoyed by future generations. As it relates to international concerns, the idea being discussed here seems to be to shape part of Canada’s international identity by its geographical landscape that would then work in tandem with the tourism industry. It is this point that leads into the discussion of international responsibilities.21

Trudeau was concerned about human rights and equality, not only in Canada but internationally as well. This Throne Speech emphasized the importance of Canada’s obligation to offer humanitarian aid. He was particularly concerned about several important international concerns occurring at that time: the Vietnamese War, the civil unrest in Nigeria, and rising communism and human rights concerns in Czechoslovakia. In fact, the Speech made a direct promise to offer permanent homes in Canada to Czech refugees. However, because of the “slow progress” and “deeply concerning” turn of these international issues, the government would choose to focus more closely on domestic concerns rather than international ones.22

At the end of the Speech, it reiterated its priority to address the concerns of the Canadian people, and the importance of protecting the populace and protect democracy in light of the tenuous global situation. Reiterating the idea of parliamentary reforms, increased social equality, economic growth and opportunity, and natural conservation, the speech ends on a note that speaks to the core concerns of the Canadian people, and related strongly to what Trudeau believed sat at the heart of what it should mean to be a Canadian; strongly focused on the idea of human rights and equal treatment for all people, the Speech leaves the reader with the strong impression of the need to cherish and protect this aspect of Canadian identity.

Speech of the Throne, 1980

In many ways, this Speech from the Throne represented new beginnings for the Trudeau Administration as well as for the country. It was delivered on April 14, 1980 by the Governor General, the Right Honourable Edward Richard Schreyer, opened the 32nd session of parliament.23 Trudeau was fresh out of a federal election victory, which had immediately followed his announcement that he would step down as leader of the Liberal Party following his election defeat that had been just nine months earlier in 1979.24 This speech was also delivered on the heels of a royal visit from Prince Charles, the Prince of Wales, and acknowledged gratitude for the royal visit, and announced the excited prospect of two more royal engagements happening soon. The Speech noted Canada’s close Commonwealth ties as well, making note of the royal accession of the Netherlands’ Princess Beatrix.25

Like Trudeau’s first Throne Speech in 1968, this one too focused on Canada itself, with Trudeau including comments on how he and his wife had the opportunity to see every provincial capital and their plans to make another cross-country trip to see smaller communities, engaging with the Canadian people more directly and personally. This Speech very much spoke of national pride before turning to parliamentary goals for the upcoming session. 26 The acknowledgement of meeting Canadians was clearly aimed at addressing the divisions in the nation. After all, Trudeau had just been returned to a majority government but his party won only one seat west of Ontario-Manitoba border and he faced the prospect of a referendum in Quebec on sovereignty-association.27 The nation was divided.

The Throne Speech recognized that division and noted: “Canada faces many challenges”, but offered a positive outlook with the idea that a united Canada can overcome any obstacle.28 It then outlined Trudeau’s priorities, including the need to address Parliament and introduce new and much needed measures to deal with pressing matters. He wanted to focus on creating security for the elderly, equality for women, opportunities for youth, stimulating the economy, improving Canada’s international influence and relations, and strengthening national institutions that work collaboratively with the provinces and territories. It was an agenda that resembled some of his priorities from 1968, and addressed once again the issue of Canadian unity.29

The Speech makes no effort to mask Canada drastic social divisions and civil unrest, from the Atlantic, to Central Canada, to the West. It addressed the various grievances held in different parts of the country, and vehemently stated that this new federal government and its parliament would commit itself first and foremost to the promise of uniting Canada and adhering to the core ideals of what makes the country work. It promoted Canada as a country strong in the loyalty of its people, a country of diversity that promoted enterprise, a country that shares its wealth with the needy, and a country responsive to the needs of the world at large. It was a vision of Canada that Trudeau believed captured the sentiment of a united Canada, but in his 1980 Throne Speech he made specific reference to the upcoming Quebec referendum. More pointedly, he asked the question at the beginning of a new decade, would Canada survive through the 1980’s as a united country?30

The Speech then presented a five-point agenda that the government believed was necessary to focus on for the country to move forward. The first addressed the economic hardship Canadians faced as they moved into the 1980’s, believing that Canadians were “sensible” and “will accept sacrifice” in order to weather the storm of rising global inflation and increased financial strain.31 Showing Canada as a caring nation, Trudeau announced that the government would dedicate what limited federal resources there were to help those Canadians in need. Particular mention was made for those home owners facing foreclosures, small business entrepreneurs facing a dim prospect, and farmers facing uncertainty, though it does specifically make a point in saying that no subsidy programs for these groups would be implemented at that time. Conversely however, the government’s plan included an immediate monthly increase to the old age pension system, making specific note that it would greatly benefit single pensioners, the majority of whom were women, thus bringing in a feminist humanitarian policy. Similar measures emphasized the importance of human rights in terms of the economy, discussing how it was crucial and a top priority of the government to act as a leading force in the equal opportunity for marginalized groups, including the training and hiring of diverse Canadians, including Indigenous people, the physically or mentally challenged, youth, and women. The Speech also promoted protecting the rights of these groups, including making changes to the Criminal Code for crimes of violence against women in particular.32

The Speech went on to address the energy sector, and placed great emphasis on the need to secure Canadian ownership and responsibility of its own oil and natural gas resources. Amidst recent increases in the price of energy, Trudeau was determined to use Canada’s reserves for the benefit of the national community even if doing so alienated the energy-producing provinces such as Alberta.33 To achieve his objectives, the Throne Speech promised several measures, including the idea of introducing a Canadian-made oil price to lower costs for consumers, the need to divert use away from oil towards natural gas and electricity for conservation efforts, to increase federal funding to Petro-Canada as a key corporation in the industry, and to engage in new negotiations for oil and gas trade internationally.34

The first and second parts of the Throne Speech closely relate to the third element, which, focused on rebuilding the economy. Trudeau recognized the problems created by a rising federal deficit, saying that while this government planned to reduce the deficit, it would not entirely eliminate it at the potential cost of other important initiative included in the Throne Speech. He then outlined key steps the government would take to stimulate economic growth, including an emphasis on the Food and Agriculture industries (becoming increasingly important in the 1980’s it claimed), a renewed focus on safe and reliable transportation services, improved access to revenue from fisheries, and improved science and technology industries to diversify and enhance the economy. Emphasis was also placed on keeping the economy Canadian-owned, and he promised to make revision to the Foreign Investment Review Act that would lead to greater opportunity for small Canadian-owned business to grow and expand in competition with larger corporations.35

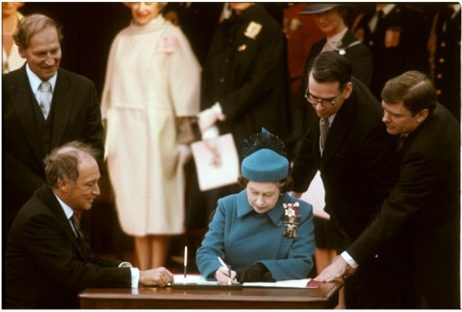

Trudeau was also concerned with how the government operated as he had been in 1968. Consequently, the Throne Speech provide a plan to deal with national institutions to create a more efficient, effective, and united federal government and country. To this end, Trudeau planned to not only review electoral reform to make it more representative and just, but also to renew the constitutional efforts to repatriate the constitution to include a charter of rights and freedoms. Such an initiative would enshrine language equality and provide equal representation for both English and French speaking citizens. Transparency within the government was also promised, noting in particular, plans for a Freedom of Information Act and the removal of the right by Ministers to withhold federal information from the courts. All of this was designed to create trust between the government and the people. The Speech discussed the idea of RCMP reform and review, and increasing the security of individual’s information and use of it.36

Foreign policy was also included as a key component of the Speech. While the section was brief, its message was clear: the government promised to take a hard-line stance against the arms race. In fact, the Speech even uses the phrase “suffocate the deadly growth of nuclear arsenals in the world.”37 To achieve this end, the government announced plans is to commit itself to a strong NATO defence pact while engaging in disarmament talks with nations around the world.38

As a final item, the 1980 Speech from the Throne offered a short commentary on the rising feeling of Western alienation, which was promptly dismissed with the statement that parliamentary members needed to better represent their constituencies to the federal government, while also properly representing the federal government back home.39 As was discussed previously, Trudeau did not have a popular standing in the Western provinces, thus adding to their growing feeling of being unheard and underrepresented, being “alienated” by the federal government. This sentiment was so strong that it caused Trudeau to directly address it in closing this Speech.

Comparison and Analysis

Both of the Speeches from the Throne from 1968 and 1980 provides valuable insights into the state of the country at the time, as well as into the mindset of Pierre Trudeau upon taking office and after more than a decade of being Prime Minister. While they contain much in common in terms of content, the tone and delivery of these speeches stand in stark contrast to each other. They also show an interesting dynamic of shifting perspectives and approaches in handling very similar concerns and issues.

The 1968 speech delivers a tone of refined dignity, using advanced language that impresses upon the audience the intellect and competency of the government and of Trudeau himself. Such a rhetoric might have been embraced specifically to showcase his higher education, but it had the effect of making the speech less accessible to the general populace as it was laden with more dense terminology and phrasing. What is clear from this speech though, is that while it takes aim at addressing the concerns of the Canadian people, the speech itself was not directed towards the populace, rather it is directed to the parliamentary members. This contrasts markedly with the 1980 speech, which uses much more simplified language and attempts to speak directly to the Canadian people in addition to addressing the Parliament. Trudeau seems to be trying to address the rising movement of malcontent across the country; while both speeches address the need to unify the country and bring the people together, such a message is much more pronounced in the 1980 speech due to the much more prevalent instances of dissatisfaction that can be found in the Quebec referendum and the Western alienation movement. Also, because of these things, the 1980 speech presents a more pronounced note of impatience and frustration that the country is not as unified as what had previously been hoped.

The content of the speeches are remarkably similar, addressing many of the same concerns such as the necessity of spurring economic growth, focusing heavily on domestic concerns rather than international ones, creating a more efficient and accessible parliamentary body and process, and preserving Canada both as a country of civil rights and liberties but also as a geographical beauty. Yet, once again, the delivery of these issues are achieved in different ways. In the 1968 speech, a more direct and detailed explanation of how the government plans to meet these goals was outlined, including specific targets to meet and pieces of legislation that were to be brought before parliament. In the 1980 speech, a more generalized approach is delivered, offering only a few instances of detailed planning but focusing more intently on the overall goal the government hopes to achieve in each policy area consider. With this as well, the 1968 speech provides a much more positive outlook on the national and global situations, making reference to the strength of Canadians, the opportunities of the country, the beauty of it, and so on, whereas the 1980 speech quite starkly discussed the difficult climate Canadians faced both domestically and internationally. It even speaks to the very bleak and difficult times ahead and the challenges that will be faced in the ensuing decade.

Considering those two Throne Speeches, what does it say about Pierre Trudeau as Prime Minster? How has he shaped Canada’s national identity today? To first tackle the question of Pierre Trudeau, the answer lies in the themes present throughout these two speeches. For example, when looking at the 1968 speech, it is clear that as a new Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau wanted to introduce his government with a sense of grandiosity and accomplishment, unveiling an ambitious and detailed plan for bettering the nation. With the central focus in 1968 being placed on human rights concerns in almost all sectors of the speech, Trudeau distinguished himself as a leader working for the people, rather than just ruling over them. His clear vision for the country was also unwavering, as seen in the 1980 speech, and it was that steadfastness that continued to drive through the importance of Canada being distinguished as a country of civil liberties and equality. Yet, because of the complexity and sophistication of the 1968 speech, it made the 1980 speech much more pronounced in its pointed directness and simplicity, signifying a change in attitude and perspective on behalf of Mr. Trudeau. That note of impatience shines through much more brightly as a result, bringing forth the obvious tensions felt across the country and the increased challenges facing Trudeau’s vision for a united country. In light of this, it makes him, as a Prime Minister, seem almost stubborn in adhering to his original vision for the country without much (if any) change in the direction he hoped to take. While much can be said on this matter and approach in terms of Trudeau as a person and politician, the impact on is also clear: because of his unwillingness to compromise his vision for the country, he continued to push through an agenda focused heavily on domestic concerns centered around creating economic opportunities to a more socially equal society, and because of this, Canada today still strongly identifies as a country of civil liberties and equality

Conclusion

Both of these Speeches from the Throne provide an incredibly interesting and insightful glimpse into not only the situation in the country at the time when each Speech was delivered, but also into the development of the man behind the speech, Pierre Trudeau. From his first time in office in 1968, until when he was re-elected to office in 1980, his approach in addressing his government and the Canadian people evolves from a more formal and rigid stance into a direct, upfront, and almost impatient tone. While the speeches themselves contain much of the same content in terms of nationalism, economy, international affairs, and more, the delivery of the speeches stand in stark contrast with each other and show a clear evolution of Trudeau’s plan for uniting a divided country. Clearly the state of discontent in the country, which threatened of his central goal of unity, was a great source of strain within the inner workings of the government and with him personally. Despite this, however, the ideas of social equality and human rights advocacy continued as strong themes that persisted in both speeches, evolving over time to reflect the shifting needs of the Canadian people. Trudeau’s ongoing commitment to fighting for human justice is what ultimately shaped an important aspect of the Canadian national identity. Without his vision for the country, Canada’s sense of national identity today would not include such an entrenched aspect of civil liberties and equality.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

“Speeches from the Throne” ParlInfo, Library of Parliament Canada, https://lop.parl.ca/sites/PublicWebsite/default/en_CA

“Governor General of Canada” ParlInfo, Library of Parliament Canada, https://lop.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/People/governorGeneral

“Senate Minutes of Proceedings, 28th Parliament, 1st Session” Canadian Historical Resources Database, Library of Parliament Canada, 13-14, https://lop.parl.ca/staticfiles/ParlInfo/Documents/ThroneSpeech/En/28-01-e.pdf

“Senate Minutes of Proceedings, 32nd Parliament, 1st Session” Canadian Historical Resources Database, Library of Parliament Canada, 8, https://lop.parl.ca/staticfiles/ParlInfo/Documents/ThroneSpeech/En/28-01-e.pdf

Secondary Sources

“When Pierre Trudeau Became PM for a Second Time in 1980” Archives: CBC News, February 18, 2019, https://www.cbc.ca/archives/when-pierre-trudeau-became-pm-for-a-second-time-in-1980-1.5002218

Clarke, Harold D, Jenson, Jane, LeDuc, Lawrence, and Pammett, Jon. “Voting Behaviour and the Outcome of the 1979 Federal Election: The Impact of Leaders and Issues.” Canadian Journal of Political Science 15, no. 3 (1982): 517-52.

English, John. Citizen of the World: The Life of Pierre Elliot Trudeau Volume One 1919-1968. Toronto: Vintage Canada, 2007, https://tinyurl.com/y2lg2wwf

Kenneth, Carty R. and Ward W. Peter, Entering the Eighties: Canada in Crisis. Canada: Oxford University Press, 1980) 147.

Laxer, James and Robert Laxer. The Liberal Idea of Canada Pierre Trudeau and the Question of Canada’s Survival. Toronto: Canadian Electronic Library, 1977, https://www-deslibris-ca.libproxy.uregina.ca/ID/413575

Palmer, Bryan D. “Canada’s “1968” and Historical Sensibilities.” The American Historical Review 123, no. 3 (2018): 773-78.

Zolf, Larry. Just Watch Me Remembering Pierre Trudeau, Toronto: DesLibris. Books Collection, 1984, https://www-deslibris-ca.libproxy.uregina.ca/ID/413563