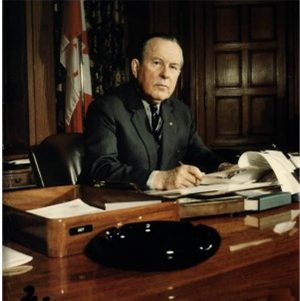

3 Lester B. Pearson’s Quest for Progress and Canada’s Centennial Year: Speech from the Throne and Leaders’ Day Reply, 1967

Joshua Switzer

Introduction

National progress, as political virtue, is an obvious choice for politicians to include in their speechmaking rhetoric. For some Prime Ministers of Canada this stands true in their Speech from the Throne and Leaders’ Day Reply (also simply known as the Reply to the Speech from the Throne). In the same breath, does progress also mean that Prime Ministers merely provide lists of answers to ordinary Canadians in every single speech produced? In the Throne and Throne Reply speeches one can most definitely find examples of progress-driven language on the state of the economy, research and development, social and state relations, resource management, international intentions, party platforms, and other themes typical of any parliamentary speech. Prime Ministers also attempt to envision what Canada means for Canadians – in the present and for the future. The Speech from the Throne and Leaders’ Day Reply from Lester Bowles Pearson, 14th Prime Minister of Canada, casts its light over some unique matters. Both Speeches traditionally emphasize the policy objectives of government. Some commentators and academics see such skillful speeches as being designed to gloss over matters with intrigue and in dressed-up language, however. Clichés pervade these speeches as well.

What is often created, though, is a pleasant and, simultaneously, serious dialogue with Canadians and this, I maintain in this chapter, was Pearson’s intention in his 1967 Speech from the Throne. As much as it was an ode to the Fathers of Confederation, Pearson wanted Canadians to share their pride amongst one another by celebrating the progress of the nation of Canada. There is more to both Speeches than meets the eye, however. The Speech from the Throne in 1967 was read by Governor General Roland Michener and more importantly it conveyed Pearson’s political ideals, values, and visions, evincing rhetorical prowess and sound judgement. Pearson’s Throne Speech and Reply from May of 1967 showcase some rather interesting themes that typify his time in office as Prime Minister; he wrote modestly with no contrived language in these speeches, and seemed to speak directly to Canadians1 and, if not for himself or his party, in honour of the country. But the question still begged is whether or not the Speech from the Throne and Leaders’ Day Reply from Prime Minister Pearson departs as a message to Canadians as only a political promise; national and international matters are reined in by leaders when they solidify and legitimate their position abroad and garner support from the civilians of their country.

This paper’s analysis will be tied together with certain threads that stitch together a larger picture: Pearson’s political ideals in three themes. It must be said that many of the sections from both speeches are outside the scope of this essay; such an approach ensures a more specific, instead of a generalized, thematic direction to understanding Pearson as that moment in Canada’s history. After touching on some of Pearson’s political ‘highlights’, a narrative on the three themes will start to take shape: Pearson and Confederation as it pertained to the centennial year, Pearson and the provinces on questions surrounding the Canadian Constitution, and Pearson’s inherent internationalist leanings while in office. These themes will be given due attention within the appropriate context of each in relation to the larger theme of progress that Pearson promoted.

Brief Secondary Literature Overview

There is not a great deal of scholarly work that has been written analyzing Canadian Prime Ministers and their vision for Canada as outlined in the Throne and Leaders’ Day speeches. As such, this essay offers a new, fresh approach to Canada’s political history; such an approach is an act of continuity that narrates not just on an academic level but also on a public one; finally, it navigates through the vast terrain of Canada’s political traditions. Much of the literature cited in this essay provides a context for each discussed; the Throne Speech from May 8th and Leaders’ Day Reply from May 10th focus in on the primary and secondary literature themes and topics that intersect and overlap. The essay’s secondary literature is supplemented by Canadian political and social history and more specialized articles on Pearson written in the last 20 years, and what he accomplished with a twice-elected minority government for five years. Among the important studies of Pearson in politics include Pearson: The Unlikely Gladiator edited by Norman Hillmer. A good overview of the political climate of Canada in the 1960s is provided by Lara Campbell, Dominique Clement and Gregory S. Kealey’s Debating Dissent: Canada and the Sixties. The ‘political brand’ of Pearson will be supported by work from Michael Bliss’s well-known Right Honourable Men: The Descent of Canadian Politics from Macdonald to Chretien. Other secondary sources appropriated into certain sections of the essay are also important and is mentioned – in-text or footnotes — as the paper progresses.

Approaching Lester Pearson and the Essay’s Parameters

On the home front, Mike Pearson (as he was sometimes called) was a practical and pragmatic politician given to accommodation; globally he strived for mutual understanding with other world leaders.2 From 1963-1968, Lester B. Pearson improved social programs, many of which are still in effect today, such as the Canadian Pension Plan, universal healthcare and national student loans. He became the first Prime Minister to visit France (1964), signed the Auto Pact (1965) with the United States of America, and appointed two Royal Commissions dealing with challenging social and cultural issues: women’s status in Canada and bilingualism and biculturalism. On the international level, today, we remember Pearson for his peacekeeping. Finding a solution to the Suez Crisis was Pearson’s first most important moment on the international stage, and it defined him as he won the 1957 Nobel Peace Prize for his gallant efforts. We can also contribute his international traits to his governing style, a more interesting term: middle-powermanship. Placing Pearson in each of the following boxes — capacity, concentration, creativity, coalition-building, and credibility – establishes a series of interlinking narratives about Pearson’s Canada – a nation between smaller and larger countries within the arena of international activity and taking particular and reasoned positions on foreign conflict.3Pearson was also known as a liberal internationalist and neoliberalist, but only in certain contexts. For the latter we can draw upon Michel Foucault’s gouvernementalite (any matter ‘concerning government’). Within this concept is the notion of classic liberal structures of society and economy turned on its head: refashioned as a relationship that balances social individualism and economic maturity of a nation, and its adherence to the state by supporting the basis of government decisions.4

Pearson’s motives in the 1960s stemmed from his past experiences in the political arena. His political footing as described in this essay is rooted in “retrospective significance” — a rather objective task — which peers into a past within a past.5Historians are constantly recasting historical actors and their stories reflectively. While it may be debatable, a narrative often unfolds in the retelling of history; the past is left in its place and a version of that past is put under the microscope, viewed as a production of significant events and developments which recreates the actors and their mentalities.6 Since this essay is a product of what emerges when one approach primary documents though the lens of empiricism and reads into the connection between political power and persuasion and how they operate within the purview of one democratic leader, there are surely going to be unavoidable overlaps that create inherent silences in the narrative in its attempt to set up a methodology when discussing politics. There are limitations in what I will say about Lester Pearson’s vision of Canada viewed through the rhetoric of speech. Therefore, I have to point out that however useful it is to look at these Throne Speeches with a sense of wonder, looking back in history at how wonderfully versed and terse these Prime Ministers were in reassuring Canadians of their vision for Canada, I ask (and declare, all at once) how important this essay’s analysis unearths historical actors and puts them in their proper place contemporarily – in this case, it is about actors who evaluate and envisage their country. The essay reinforces this idea, and adds to the impressive compendium of topics and chapters in this book on Prime Ministers, as scholarship in this area of history grows. The essays are useful projects for contributing to a snapshot of micro political history. I contend that the argument of this short essay is constructivist in that it values form, content and narrative in lieu of fact and truth-seeking metanarratives.7

The Path from Confederation to 1967

Confederation was the rock on which Canada was first conceived. The truth is, there is not one ounce of doubt Pearson would not have included the importance of Confederation in his Centennial Speeches. What primed the theme of Confederation relevant to 1967’s Canada in his speeches were intertwining themes such as the capacity of the federal system, the pivotal role of establishing provincial relations, “public responsibility”8 and other currents of thought which brought together the idea of a tribute to the “men of many races, creeds, and tongues”.9 Ultimately it was their “wisdom and foresight” in founding a country that was being celebrated.10 Pearson candidly acknowledged Canadians’ view of Confederation from the point of view of “succeeding generations of men and women” had changed and evolved in a positive way, and that our national unity has “preserve[d] the whole”.11 Speaking on behalf of the nation in the Speech from the Throne, Pearson said that “the path of Confederation has been beset with great difficulties – some neutral, some inevitable and some of our own making”.12

Pearson sowed the seeds of a promising future, however, nobly proclaiming the rightfulness of Confederation in the history of Canada that Centennial year – the idea that Canada had made it through some rocky times, but here it was, flourishing 100 years later. He referenced responsibility and opportunity within the context of how Canada had grown from a minor to mature nation. This is not to say that the celebratory aspect of the centennial itself “did much to mask the troubled and uncertain decade”13. The Centennial speeches instead defined notions of nation-building from the time of Confederation. Although his Throne Speech played to the tune of economic nationalism, something Pearson was well-known for while in office, Confederation signaled the progress of Canada from 1867 through to 1967, relative to the political branding of the Pearsonian slogan for signifying nation-building. To Pearson, Confederation was personified as a beacon of progress. The Centennial was, after all, the ultimate example of how far Canada had come as a nation. In his speeches, the topic of Confederation was given ample room to extrapolate and plot out a narrative of national progress. It is as if the historic event of Confederation was a prognosticated “concept” predicated on the Fathers’ efforts for cooperative and “constructive work of a magnitude and in the face of obstacles never before tackled anywhere in the world”.14 This is the D.N.A of Canada – as an ever-growing nation, susceptible to bumps-in-the-road, with a multi-layered and complex history from its inception.

The promise of a bright future for Canada came from its proud past: “As we observe this year the beginning of a new century of Confederation,” he said, “we who find ourselves in positions of authority must always remember that it is our responsibility and our opportunity to serve the needs and aspirations of the Canadian people”.15 Pearson, in both the Speech from the Throne and Leaders’ Day Reply, projects confidence across the board even though the country had been more difficult to run in 1967 “than the unitary centralized government which Sir John A. Macdonald and many others wished for in 1867”.16 We can also observe Pearson’s speeches as inheriting the essence of Canada, something the Leader of the Opposition and previous Prime Minister John Diefenbaker and even Prime Ministers before him could not call their own. The Fathers were undivided in their aspirations to find a definition of Canadian-ness — or a new version of British-ness, back in 1867.

Pearson sought to modernize this theme in evaluating the evolution of the Dominion of Canada for the last 100 years. Even the symbols of national unity Pearson ushered in the mid-1960s were important to the concept of national identity; they spoke volumes of how the country continued on the same path from Confederation. The Maple Leaf Flag (1964) and the creation of the Order of Canada (1965) acted as pre-cursor supports for bolstering national identity. Pearson is respected today, but we cannot put him in the same league as those great Prime Minister’s like Macdonald, Wilfrid Laurier, or even Mackenzie King. Michael Bliss in Right Honourable Men tells us that “by the end of the centennial year, Pearson was largely a lame duck, presiding over a Cabinet that had lost a sense of where it wanted to go”.17 As Bliss opines, Pearson was the type of leader who knew his limits and chose not to surpass them. Pearson was a “transitional figure” who kept a steady hand on the wheel.18 The imprint Pearson left on the Liberal mold was a brand of politics that has somewhat been put to the back of our recent memory’s catalogue of Prime Ministers, but he no longer is underappreciated in Canadian history. Bliss’s metaphor of Pearson’s impact on our country, as a leader, is that of a pitcher in baseball, Pearson’s mainstay sport: although he was a consistent and reliable enough middle-inning, short duration pitcher, Pearson’s only real strength was to “keep his team in the game”, game in and game out, gracefully bowing out when he felt he needed to. No bright spots – he just had to keep it simple.19

Constitutionality and Federal and Provincial Relations

Some see Pearson as either a harbinger of dividing equal attention between cooperative and classic federalism, or as a Prime Minister who brought in a different approach to help iron out issues on provincial-federal unity. 1967 was near the end of Pearson’s tenure in office, so by the time of his Centennial speech and reply the federal government’s promises on provincial matters came out bluntly: “I believe the federal government”, he said, “has a duty to suggest new ways in which it may help the provinces and the municipalities, without interfering with their responsibilities to cope more effectively”.20 Questions loomed over constitutional representation, provincially, and patriation, federally. For Pearson, these issues relentlessly reared their unwanted heads into the political picture. Amongst many agenda issues, the provinces created rifts between them and the central government. Provincial-federal matters in the 1960s were not cookie-cutter problems, nor could they be fixed in a roundabout fashion; each premier had his own platforms to stand on, calling on the federal government by 1964 to amend provincial rights and the British North America Act of 1867. They did not need any explanations, just action — to ensure that things would not stay the same under Pearson. In Pearson’s Throne Speech, pluralism (allowing group diversity and individualism to flourish in society), rural community building, urban initiatives and resource management geared Pearson’s rhetoric towards capitalizing on Canada’s internal relationship with each of the provinces and territories.21 Moreover, noting the constitution’s “structure [which] has endured and served so well” allowed a light to be shone onto the theme of progress and Canada’s preservation of democratic politics and liberal values.22 These, within Pearson’s Liberal theory of P.O.G.G. (peace, order and good government), highlight the importance of federalism and the constitution. The significance of the constitution within the theme of federal-provincial relations comes out in his Leaders’ Day Reply:

Today the constitution remains the most important single element in our government. In some ways, perhaps, it is the most important single element in our achievements. It is the source of the rights and jurisdiction of the provincial as well as the federal governments. It is a protection for all the people, especially minorities. So an obvious and vital factor in our national growth is our constitution.23

He was criticized by Diefenbaker in the reply, and Pearson responded frankly: “Canada has shown by its own record of achievement that a federal system does not mean weakness at any level and that a country can develop under a federal system of government”.24 Cooperation between the provinces and the federal government was, to Pearson, a stronghold built upon federal and national heritage: “[The Fathers] built according to a federal plan because they knew that unity, with cultural and regional diversity, could be harnessed to a positive and enriching role in no other way”.25 This extended into the realms of rights for women, minority groups, and French-Canadians; for example, the appointments of Bilingualism and Biculturalism, and Women’s Royal Commissions overhauled the nationalist agenda in favour of keeping tabs on all geo-political and socio-political matters. Be it cultural or regional differences, gender empowerment or racial equality, solidarity could only come from below, but it started with a common bond. Freedoms for the provinces such as shared policies and joint-programs were discussed openly as programs of nation-building. Enlarged spending power and a fair division of attention between social and political issues were high on the list for Pearson, as the 1960s represented a time where people, more than ever before in twentieth century Canada, “raised questions about the capacity of governments to control their lives and protect society from the excesses of corporate greed.”26

The rhetorical seeds of opportunity and responsibility were sown into the Centennial Sessions. Reconfiguring the constitution was partially secondary in 1967. Pearson desired that Canada’s economic sphere of influence, internal protectionism and foreign affairs took priority. But the following year demonstrated that the provinces could up their anti as they volleyed for more guarantees and protections such as language rights and financial support from the federal government. To make things more complicated, Quebec began to regard itself as having ‘special status’ claims within the constitution framework showing the constraints of the Pearson period.27 Pearson attempted to right the wrongs of past Prime Ministers by showing adversaries like Diefenbaker to see the real picture for what it was: that Canada was still, by 1967, one nation and not two. In his Leaders’ Day Reply to Diefenbaker, who had said that Canada was never in such a state of division before in its history, Pearson spoke about compromise and accommodation: “language and cultural differences introduce politically complicating as well as nationally enriching elements in our society”, setting the stage for 1968’s constitutional talks.28

Pearson’s Rhetoric of Internationalism

Pearson was indeed a person who had a mission for peace and international involvement. Peace was no better exemplified than in Pearson’s views on Vietnam, showing stamina and surety of conviction:

I do not think it would improve our opportunities on working for peace if we took an active position as a government, with the responsibility as a government, on one side or the other in the particularly difficult and dangerous situation in Viet Nam, because it is a dangerous situation and is, I think, causing more anxiety today than it had at any time since I have been trying to follow it.29

Even in praising Paul Martin Sr. in the Leaders’ Day Reply by going so far as to say “there is no person in the western world who has worked harder to bring about negotiations of peace”,30 his political ideals yield to larger forces, in close proximity with international affairs. The issues of foreign investment in Canada was brought about by Walter Gordon who influenced Pearson to adopt a conservative nationalist government by the late 1960s.31 What then, was there to protect Canada’s domestic interests? This was the first serious question for Pearson: there had to be some yielding to the temptation to associate too closely with others, even our southern neighbors. American investment was criticized by the left in Canada, some of whom supported Pearson.32

Thus, Pearson had to find ears elsewhere. In the international arena is where Pearson can be credited for what some call quiet diplomacy. He was not an anti-continentalist but he was a vehement opponent of anti-American sentiment in Canada33 in keeping with the tradition to have bilateral trade relations stay afloat. But he was not about to aide America militarily by sending troops to Vietnam. Nation-building, then, was not an America-Canada nationalist contest to Pearson. The past spoke volumes about his international involvement. Ultimately he was helping to develop “discourses in which Canadian distinction could be remarked upon and celebrated” at the international level.34 To quote Jack Granatstein: “[the] Yanks fought wars, Canadians said…while Johnny Canuck kept the peace…Peacekeeping was so popular…primarily because it was something we could do and the Americans could not.”35 The international stage that Canada shared was with the United Nation, N.A.T.O., and other institutions where countries who were considered partners or allies could come together. Canada’s plans for external aide and international trade were among some of the topics included in his speeches.

His Centennial Speeches remind us, however, of his unshakable confidence in his government’s global vision. Canada’s government to Pearson had to be functional at home and abroad. In his 1967 Throne Speech, peace, disarmament, and all matters of diplomacy-through-settlement were persuasive in that Pearson subtly was calling on other countries’ leaders to realize that a “concerted international endeavour” must be undertaken if progress was to be met with satisfaction.36 But these were mere words on paper, possible worlds of actions. Pearson’s sanguine good nature coupled with a peaceful international image was constructive. Pearson’s interest in international affairs was actually conceived early on in his life; he, like others his age, was influenced by his generation’s experiences from The Great War. Militancy and opposition attitudinized Pearson’s stance on foreign conflict which took precedent over “pre-constitutional” matters.37 It’s not that constitutional matters were less important for Pearson but that “dramatic threats to security that in [his] day dominated the international agenda” 38 affected his political theorizing. In the international community is where Pearson’s humility and stoicism went a long way; a ripple effect throughout his development in politics:

…I do not think that as a responsible government it would be wise or desirable or necessary for us to publicly condemn or publicly proclaim. I think it is better for us to play our part as a member of the international commission and of the international community and work in a quiet, not spectacular but as effective a way as possible…39

Conclusion

Pearson said that “The speech from the throne reflect [sic] in general terms the need for government to improve the opportunities for every Canadian to live a better life.”40 A Leaders’ Day Reply, I might add, shows, on the other hand, the masterful political sparing necessary to defend one’s values. For any Prime Minister, their values are invested in creating the type of Canada they desire. Indeed, their reassurance in these types of speeches, in retrospect, give readers today that especial advantage of looking at the past with hindsight, while contemporarily people sometimes balked at and dismissed their leaders for their judgement or foresight. But Canada is still one nation, held together by the very men and women working from Parliament Hill. Pearson is one of those people who already has a place in the annals of Canadian history, who devoted much of his life to improving the Canadian political system – domestically and internationally. This essay has elucidated on some of Lester B. Pearson’s political values, nation-building projects and his themes on progress, opportunity and achievement. Through an analysis of his Centennial Speeches this essay narrates translucently just how Canada’s history, national fabric and place in the world essentially highlighted Lester Pearson’s vision for Canada on its 100th birthday.

Bibliography

Campbell, Lara. Clement, Dominique. Kealey, Gregory (eds.) Debating Dissent: Canada and the Sixties. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2012.

Canada. 1967. Reply to the Speech from the throne, second session of the Twenty-Seventh Parliament of Canada. Ottawa: Govt. of Canada.

Canada. 1967. Speech from the throne, second session of the Twenty-Seventh Parliament of Canada. Ottawa: Govt. of Canada.

Blake, Raymond. Keshen, Jeffrey. Knowles, Norman. Messamore, Barbara. Narrating a Nation: Canadian History Post–Confederation. Toronto: McGraw-Hill Ryerson, 2011.

Bliss, Michael. Right Honourable Men: The Descent of Canadian Politics from Macdonald to Chretien. Toronto: Harper Collins Publishers, 2004.

Boag, Gemma. “The Middle Power Approach: Useful Theory, Unpopular Rhetoric”. Inquiry@Queen’s: An Undergrad Journal. (2008-03-17): 1-7.

Hillmer, Norman (ed.) Pearson: The Unlikely Gladiator. Kingston, Ontario: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999.

Hynek, Nikola. Thomsen, Robert C. “Keeping the Peace and National Unity: Canada’s National and International Identity Nexus”. International Journal 61, 4 (Autumn 2006): 845-858.

Lemke, Thomas. Foucault’s Analysis of Modern Governmentality: A Critique of Political Reason. London and New York: Verso, 2019.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. Silencing the Past: The Power and Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press, 1995.