1 William Lyon Mackenzie King’s Vision for Canada

Brady Dean

Introduction

Being Prime Minister is not easy. Those who run for and achieve the position are responsible for every action that Canada takes as well as every success and failure Canada experiences during their tenure. While the democratic system divides the power and responsibility of government and statecraft among many people and institutions, the Prime Minister likely has the most important role: to chart a course for an often divided and fractious Canada. “What kind of country is Canada to be?” is a question that likely exists in the mind of each Prime Minister on his or her first day in office and perhaps is present there until their last day in the role. Fortunately for scholars of political history, Prime Ministers propose an answer to that question very frequently during their tenure, and two of the most helpful parliamentary instruments to find their proposed answers are their Speeches from the Throne and their Leaders’ Day Addresses.

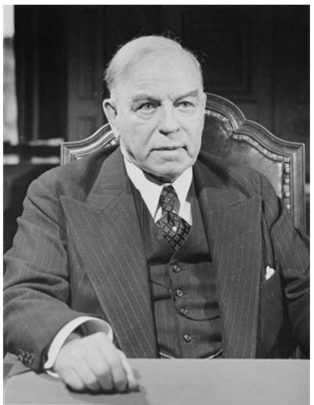

Mackenzie King, Canada’s longest serving Prime Minister, had much practice writing and delivering such speeches and addresses. Often perceived as unable or unwilling to take strong stances on any given issue, historians often view Mackenzie King with ambivalence.1 In many cases, the views of historians are valid and defendable; one only needs to examine Mackenzie King’s handling of conscription for evidence of political indecisiveness.2 However, this criticism cannot be launched against his Speeches from the Throne and Leaders’ Day Addresses. These speeches and addresses provided a clear vision of the Canada that Mackenzie King believed must come to fruition. This essay will examine his Speeches from the Throne and Leaders’ Day Addresses and demonstrate that he provided a clear, firm, and unwavering vision for Canada that centered on the country being a cooperative, supportive, and nationally united country. This essay, more specifically, focuses on years from 1936 to 1942, a period which is interesting period since the timeframe encompasses the years leading up to and including the early years of World War II. As such, the vision for Canada that Mackenzie King presented before the war’s onset is given a trial by fire as the fight against Adolph Hitler and Nazi Germany entered a dangerous phase. The period also provides an opportunity to investigate how Mackenzie King adjusted his vision from depression-era Canada to a period of mobilization for and participation in war. This paper argues that he does not make many adjustments. In fact, his vision only became further focused.

This chapter is based on a methodology that relies on an empirical analysis of Throne Speeches and Leaders’ Day Addresses by King. Through an engagement with these speeches and addresses, one is afforded a direct view of how Mackenzie King envisioned a Canada with him as Prime Minister and how he articulated that vision. Further, using both sources allows an analysis of how Mackenzie King described his vision to Canadians as well as how he defended it in the face of opposition. When looked at together, the Throne Speeches and Leaders’ Day addresses provide a comprehensive overview of Mackenzie King’s vision for Canada.This essay also attempts to understand Canada’s national identity. National identity is a difficult concept for any nation to construct, and Canada’s complicated history of bringing together several diverse ethnic communities and geographical regions only compounds this difficulty. To oversimplify the history, Indigenous people existed in what is now known as Canada long before the arrival of Europeans. France first established a colony on the North American continent in the 16th century.

Later, Britain followed and eventually won control of much of North America in the Seven Year’s War in 1763. When Canada finally became a dominion and looked to expand both in size and population, it extended its control over a large area and although it invited many different races to join the nation-building endeavour, it also left out and marginalized many others as it struggled to populate the land. The result was a massive country, with many different regions, filled with people from, quite literally, all over the world. While the diversity was a beautiful creation, it also proved challenging for its political leaders. It is nearly impossible to construct a national identity that encompasses all of Canada’s history, regions, and demography.Often, the question of Canadian national identity is contentious and has the potential to create huge schisms in the Canadian polity. Students of Canadian history can describe many tense events in Canadian history that can be connected to issues of national unity: Japanese internment, the flag debate, the conscription crisis in the First World War, and the FLQ crisis stand out. The challenge of Canadian national identity was so pervasive that it had to be present in the decision-making process of every Prime Minister and maintaining national unity has always been a priority. Unfortunately, national identity would forever be a “moving target” for Prime Ministers. As explained by Raymond Blake: “Ideas and policies that become national identity […] are subject to ever-changing contexts in the search for national well-being.”3 Mackenzie King knew this well and was petrified of making any decision that would threaten Canadian unity. This context is crucial to understanding the task that confronted Mackenzie King when he, through his Speeches from the Throne and Leaders Day addresses, explained his vision for Canada.

Before the War: Canada as Cooperator

When the 18th Parliament of Canada opened in February 1936, the nation was still very much in the grips of the Great Depression. Unemployment, while finally showing signs of improvement, was still of grave concern. Certainly, Canadians were alarmed with the failure of their governments to reduce the number of able-bodied workers receiving relief payments. It was against such a grim backdrop that Mackenzie King, through his Speech from the Throne, staked out his position on international trade and its importance as a tool for Canada to cooperate with the world. Touting the new Canada-United States trade agreement that had been recently reached as well as the continuing normalization of trade with Japan, King’s words left no question of what he thought of trade, noting that the signed agreement and the normalization of relations with Japan “will contribute to the reversal of the trend toward extreme economic nationalism, which has been undermining standards of living and embittering relations between countries all over the world.”4 King clearly — and forcefully — positioned international trade as an instrument not only of promoting peace and prosperity but also of challenging growing economic nationalism as a barrier to economic recovery in Canada and around the world. Being a shrewd politician, King was careful to paint the opposition leader at the time, Conservative R.B. Bennett, as anti-trade and an economic nationalist during his Leaders’ Day Address on 10 and 11 February 1936. While Bennett claimed that the trade agreement with the United States was negotiated too hastily, King took issue with the fact that Bennett, who was Prime Minister from 1930-1935, made no real effort to strike such a trade deal during his time in power. In pointing this out, King branded Bennett as a proponent of economic nationalism that King believed only created tensions between nations and inhibited peace.

In King’s vision, Canada was a trading nation and trade was essential for Canadian prosperity. King believed that the Canada of 1930-1935 – the Canada that he suggested employed economic nationalism under Prime Minister Bennett – was un-Canadian and he wanted to reassure Canadians that that construction of Canada was no more under his Liberal government. The Canada that King envisioned as he is spoke in 1936 was one that believed in trade with other nations. He also states that, given the strong majority the Liberal government held in the 18th parliament, as well as their resounding successes in three by-elections that took place after the commencement of the last general election, Canadians, too, agreed that a global outlook was the way forward.5In the Speeches from the Throne in January of both 1937 and 1938, King took each opportunity to prove that he was correct about the power and efficacy of international trade. Canada enjoyed a “marked increase” in trade and commerce over those years which improved its economic position internationally as well as provided a “continuance of recovery” in domestic finances, which remained hindered by the impacts of the Great Depression.6 It was also during these very same years that the situation in Europe worsened with Hitler’s violations of the Treaty of Versailles compounding the problems. King acknowledged these tensions and once again reiterated that the importance of trade as an important peace-keeping tool: “The Government is convinced,” he said, “that, in seeking to co-operate with the United Kingdom and other countries in efforts to promote international trade, it is pursuing one of the most effective means of ensuring economic security and progress in Canada, and the betterment of conditions in the other parts of the world.”7

In analyzing King’s words above, two key points emerge that help one understand the vision that Mackenzie King had for Canada during the period from 1935 to1939. Firstly, that international trade was key to peace in the world and Canada must contribute to peace by contributing to international trade rather than pursuing a protectionist and isolationist agenda as Bennett had. Secondly, international trade, he asserted, was good for Canada as much as it was for the world. By speaking of these two points so frequently throughout the years from 1935-1939 and by speaking of them usually one after the other, King carefully aligned and intertwined Canada’s domestic well-being with its international well-being. By engaging the world in trade, Canada improved the world’s conditions as well as its own domestic conditions. Therefore, the most logical and prosperous path for Canada and the path that King put Canada on emphasized the importance of international partnership and cooperation.

Before the War: Canada as Supporter of its Allies

Mackenzie King understood that Canada had much to offer the world and trade was just one of the ways it could help the world and itself at the same time. But he also understood the limits of Canada’s ability to be a true global leader. He understood that Canada would never be able to lead in the same way that the United States or the United Kingdom was able to lead – it did not have the economic or military power or other resources that would allow it to do so. Even while understanding Canada’s limitations, King believed Canada could help its allies reach their full potential. In King’s vision, Canada had to play a supporting – but important role, nonetheless.

At the beginning of 1939, war was all but certain in Europe and it was time for all nations, including Canada, to prepare for that eventuality. That said, King believed that the work of supporting the maintenance of peace must continue and he said as much during his Leaders’ Day Address that year which, primarily, was a response to the new opposition leader, Robert Manion’s address. After expounding on the success of the Liberal government in achieving a trade agreement with the United States in 1935, and the positive impacts of that trade agreement for Canadians, King explained that the United Kingdom and the United States were interested in striking a trade deal between themselves and that Canada supported such an agreement. In fact, he would help usher it along. King saw Canada as a lynch pin between those two nations and, in fact, King was willing to adjust Canada’s agreements both with the United States and the United Kingdom as a way of facilitating a trade agreement between the United States and United Kingdom.8

King took much personal credit for Canada’s generosity in adjusting its deals with the United States and United Kingdom as a way of ensuring that those two countries struck up their own deals. It was, however, an indication of King’s vision for Canada. While noting that a small cost was associated with adjusting Canada’s agreements with the economic interests of those two countries, those adjustments would pay dividends, as Canada’s role in the international community would be further solidified. Not only had Canada improved its own economic position by brokering trade deals with other like-minded nations, it also facilitated the trade deals of its allied nations and, in doing so, “has helped to make one of the most substantial contributions towards improving world conditions that has been made in this last decade.”9 Clearly, King envisioned a Canada that was a cooperator and facilitator on the world stage – it was open for trade with other nations and encouraged other nations to do the same.

Before the War: National Unity

The vision of Canada as player on the world stage had the potential to come with a domestic political cost. For any prime minister to become too close with other countries, especially with the United States in Canada’s case, could cause strife within the various cultural groups that existed in Canada. For example, historically, many French-speaking Canadians were frequently concerned with Canada becoming too close with Great Britain, and many Canadians, more generally, have been wary of becoming intertwined with — or pulled into the orbit — of the United States. Such rhetoric and perceptions were not lost on Mackenzie King and those views were likely front of mind in any decision that he would make for the country as a means of preserving national unity. Such thinking is evident in his Speeches from the Throne and his Leaders’ Day addresses prior to the war; King manifested such ideas by sprinkling messages throughout his speeches about where Canada’s allegiances truly lay. King was particularly acutely aware, especially for English-speaking Canada, of the necessity of reminding Canadians that Canada was an important member of the British Commonwealth. For him, mentions of the Crown and Canada’s relationship to it acted as a touchstone to recalibrate Canada’s position in the world and was used to reassure Canadians that Canada was not straying too far from its roots. King mentioned the Crown many times in the period before the war. Generally, those sentiments of the Crown and of Canada’s relationship to it came at the beginning of the Speeches from the Throne, especially during the period prior to the war. For example, the Speech from the Throne of February 1936 began with condolences towards the late King George V.10

The next year’s speech opened with the business of King George VI’s upcoming coronation and Canada both expressing its loyalty to the King and planning for Canadian representation at the coronation.11 The theme continued the following year when the Speech from the Throne begins by discussing the coronation ceremonies and the reaffirmation of the “relationship between the Sovereign and his peoples in the several Dominions […].”12 Placing discussion of the Crown at the forefront of the Speeches from the Throne put the relationship to the Crown at the forefront of Canadian minds, a deliberate choice by Mackenzie King who always positioned Canada as a member of the Commonwealth first and foremost. Such a tactic ensured that Canada’s expanding its place in the world through cooperation and support with, and for other nations, would not allow Canada to forget its historical origins, which could be cause for a strain on national unity. Mackenzie King’s commitment to the Crown can also be found in his Leaders’ Day Addresses, although it is in these somewhat more wide-ranging addresses that Mackenzie King carefully qualified Canada’s relationship to the Crown. To King, while the relationship to the Crown was extremely important, so too was national autonomy. While these two values may seem competing — and they were in some respects — King was careful to hold them both at once in harmony. Perhaps the clearest indication of this is a quotation by King in his Leaders’ Day address of 1937 where he states that “there is the importance of laying emphasis upon national autonomy and, on the other hand, the equal importance of laying emphasis upon imperial unity.”13 He continues to qualify his vision for Canada as both Commonwealth member and autonomous agent by saying, “there are times when it is necessary to emphasized strongly the position of our national autonomy; there are other times when it is equally desirable that the need of unity between all parts of the British Empire should be strongly stressed.”14 King’s vision of Canada as committed member of the Commonwealth and autonomous agent is even further intertwined and solidified when, during his Leaders’ Day Address during the special war session of 8 September 1939, King made it very clear that Canada must be involved in the war. He once again emphasized Canada’s historical roots as a British dominion and even utilized those roots in his rhetoric, stating that Canada had to join the side of the Allies because, after all, “where did our liberties and freedoms come from?”15 Clearly, the Canada that Mackenzie King envisioned was one that was simultaneously committed to its historical ancestors but also one which made its own decisions as a nation.

When war did eventually come, however, would King’s vision for Canada change or remain the same?

During the War: Cooperator

Mackenzie King could make any grand claim of Canada as a cooperator in peace time. In fact, the growing tension in Europe prior to 1939 only strengthened King’s claims that Canada should be a partner and facilitator on the world stage as a means of avoiding war. However, war proved to be unavoidable and King had increased Canadian military expenditure in the few years before 1939. Would the concepts that King espoused during peace time remain and continue to be pursued during war time? The answer to this question is yes, and while King’s peace time vision for Canada played an important role of keeping the world peace, the outbreak of war only served to strengthen his resolve. Canada was a partner to its traditional allies in the Commonwealth and to the US before the war to try and he even attempted to avert a conflict, but once the war began, Canada not only remained a partner but also increased it effort to wage the war against Nazi Germany to ensure that good prevailed in the battle and overcame the evil that he believed had engulfed the globe.

Early during World War II, the onslaught of Nazi Germany was frightening for King as the immediate and crushing losses grew for Allied nations. These developments would occupy most of King’s Speeches from the Throne for the early years of the war. He used these advancements of the Nazi forces in Europe to remind Canadians that Canada will be an unremitting and unflinching partner in the war effort, stating, “These tragic events have but served to intensify our determination to share in the war effort of the allied powers to the utmost of our strength.”16 King’s use of the phrase, “utmost of our strength,” is telling, and it was a clear signal to Canadians that Canada would be a partner in the war effort to the extent possible to ensure victory in Europe as Canada had done in the fight for peace during the First World War. While he stopped short of uttering the phrase “total war” at this point, King seems to have been preparing Canadians for that level of commitment. The early years of the war also allowed King to align Canada’s interest with that of those nations from which many Canadians had come and were then resisting German aggression: Britain and France. “The constant consultation and complete co-operation maintained with the government of the United Kingdom and France […]”17

Clearly, King wanted Canadians to agree that Canada had to cooperate to its fullest extent on the side of good in the battle of good versus evil to ensure the victory and that Canada find itself, at the end of war, “[…] standing, united at the side of Britain and of France.”18Unfortunately, King’s statement did not age well. In June of 1940, France capitulated to Nazi Germany. This did not shake King’s vision for Canada role in the war effort; it only shifted its focus. While the United States was not involved in the war until 1941, France’s capitulation meant that the United States was now a key ally in the fight against Germany. King reminded the Canadian people of this while also reinforcing Canada’s important role in the Allied war effort: “In the face of the common peril there has arisen a closer association and an increasing measure of co-operation between the United States of America and the nations of the British Commonwealth.”19 King’s mention of the United States alongside the Commonwealth was a harbinger of the kind of cooperation that would follow the war years. In short, Canada was seemingly ready to cooperate with any nation fighting on the side of good versus evil and he was preparing the Canadian people to cooperate fully with its two most important Allies at the time: the United Kingdom and the United States of America. For King, Canada’s security had to be ensured.

During the War: Supporter

King left Canadians with no doubt that Canada would be a key member of the Allied fight against Nazi aggression. But, as has been discussed above, Canada could not be a true global leader in this fight; it simply did not have the power or resources to do so. Its primary role would be that of supporting the larger nations and front-line fighters of the war, and it is within the Speeches from the Throne and Leaders’ Day addresses that King explains the importance of this supporting role. In fact, King brands the level of Canada’s support with a new name: total war.20 Throughout the war, King frequently expounded on the importance of Canada fully contributing to the war effort. Factories would be retrofitted to create war materials, Canada would train war pilots on its soil, and create many new initiatives to fight the good fight. In King’s words, Canada was to “[contribute] to Britain vast quantities of munitions, foodstuffs, and supplies.”21 King’s Leaders’ Day addresses during the war years primarily revolved around quantifying and defending the degree to which Canada was supporting the war effort. More specifically, King had to defend his administration’s war policies by showing that no expense was being spared in the fight against Nazi aggression. In his January 1942 Leaders’ Day address, for instance, King defended his government’s training of British pilots as being the best use of its resources so that Britain can “strike back against the aggressor.”22 Canada also had a supporter role as lynchpin between the United States and the United Kingdom, much as it had prior to the outbreak of war.23 Where Canada acted as a supporter of trade between like-minded nations before the war, it became a supporter of United States and United Kingdom relations during the war as well. Specifically, King helped to facilitate getting the United States’ resources into the hands of the United Kingdom in the fight against Germany, even if isolationists within the United States were keeping their country out of the war. He spoke of this role at length in his November 1940 Leaders’ Day address wherein he thanked the United States for their help in the war effort, whether that be through planes, tanks, materiel, and the like as well as Canada’s part in securing such help: “joint action between the United States and Canada was recognized also as necessary to their common security […] what followed constitutes the most significant development in international affairs since our parliament adjournment in August. Of ultimate importance, it far surpasses the formation of the [T]riple [A]xis.”24 The impact of Canada’s support of the war effort through fostering and nurturing joint action with the United States is not undersold by King. History would later prove that he was correct in these grandiose claims as support from the “neutral” United States helped stave off defeat of the United Kingdom by Nazi Germany. Not only was Canada in a total war footing and supporting the war effort through materiel at every junction, but it was also ensuring that the United States supported the war effort too. This was, it might be argued, Canada’s true contribution as an important partner in the Allied war effort.

During the War: National Unity

While Canada was being pushed to its limits and fully engaged in what Mackenzie King labelled as total war, the cracks in national unity which showed at the best of times had the potential to be exacerbated. As such, King had to portray Canada to Canadians and internationally as united through World War II, and his Leaders’ Day Addresses during the war years, therefore, focused much on national unity. Firstly, King made it clear that Canada must not resort to partisan infighting and must remain united. That rhetoric was certainly one way of pre-emptively hamstringing political opponents during the war, such as opposition leader Richard Hanson in the early years of the conflict and Gordon Graydon in the later years, but it also shows King’s desire for a united country with him at the helm. He argued that his government during the war was exactly what the people wanted, and he claimed to have the strong mandate of the Canadian people, citing his strong 1940 election victory as evidence.25 To King, Canadians want him in Ottawa leading the nation and they were united behind him. His only goal — as it related to national unity during the war years — was to assert that Canada was, indeed, united and the only threat to that unity was the leaders across the aisle.This rhetoric continued when King frequently criticized the opposition leaders for playing politics during such a time when what the nation required was strong unity: “[the war] needs and will need the utmost vigour and whole-hearted assistance on the part of each and every one of us.”26 This is not to say that Canada was operating completely independent of Great Britain. King deflects Richard Hanson’s attempts to paint him as not being loyal enough to the Crown by saying “[I] have the strongest admiration for Britain” and he chastised Hanson for trying to create division by saying: “I see no reason for drawing a line between our respective loyalties.”27 Thus, by dismissing these criticisms and, in fact, criticizing Hanson for launching such divisive language, King’s position on national unity put forward in his speeches during the war was evident: Canada was united, and any criticism of his strongly-elected national government only actually serve to foment disunity. Perhaps the best illustration of King’s vision of the united Canada during the war can be found in an already-referenced statement he made in May of 1940, while the war was not going well for the Allies: “the end of the war will find the people of Canada, where the beginning of the war found us; standing, united at the side of Britain and of France.28

Evoking a victory achieved in partnership with those nations from which Canada’s two major cultural and ethnic groups descended was King’s most powerful statement to reinforce national unity.So, too, was his strategy on conscription. In the early years of the war, it quickly became clear that even more soldiers would be needed than already provided and were later volunteering. This need led to a national discussion of conscription and whether it would be necessary to enact to sustain Canada’s war effort. King, extremely wary of the impact on national unity that conscription would have given the divisions it caused in 1917, he delayed as long as possible to avoid straining national unity and he initially instituted only half-measures to placate the advocates of conscription. In 1940, King introduced conscription but only for the purposes of defending Canada and not for sending soldiers overseas. In 1942, a plebiscite was held to release the Canadian government from its promise of not sending those conscripted men overseas. In 1944, King reluctantly sent men overseas. French Canada showed its dismay with this decision and national unity was strained. Despite this, this strain was eventually lifted when, in 1945, the war came to an end. A relieved King was able to maintain national unity while fulfilling Canada’s war effort, perhaps one of the most difficult issues of his tenure as Prime Minister.29

Conclusion

The reputation Mackenzie King has today – that of equivocating and indecisiveness – certainly did not come from the speeches examined in this paper. These speeches show a clear vision of Canada, both before and during the war. What is also interesting is the fact that the war, likely Canada’s greatest test it had had to that date, had no real effect on King’s vision of Canada. In fact, he may have doubled down on that vision during the war. The Canada that King described prior to the Second World War came to fruition at the onset of the war and he remained the course throughout the conflict. One may even speculate that King prepared Canada for its ultimate test by charting his vision for Canada prior to the war and then staying the course once fighting began. The result was an impressive showing in the war and the emergence of a stronger, more united Canada that understood the impact it could have on the world with a visionary leader like Mackenzie King at the helm.

Bibliography

Blake, Raymond. “William Lyon Mackenzie King’s Role in the Reconstruction of NationalIdentity.” TheCanadian Historical Review 101, no. 3 (2020): 370-396.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 6 January 1936.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 10 February 1936.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 14 January 1937.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 18 January 1937.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 27 January 1938.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 16 January 1939

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 8 September 1939.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 16 May 1940.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 20 May 1940.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 7 November 1940.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 12 November 1940.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 22 January 1942.

Canada. Parliamentary Debates. House of Commons. 26 January 1942.

Dummitt, Christopher. Unbuttoned: A History of Mackenzie King’s Secret Life. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017.

Granatstein, J.L. Canada’s War: The Politics of the Mackenzie King Government, 1939-1945.Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Granatstein, J.L., and Hitsman, J.M. Broken Promises: A History of Conscription in Canada. Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1977.

Levine, Allan. William Lyon Mackenzie King: A Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny. Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2011.

Neatby, H. Blair. William Lyon Mackenzie King, Volume III, 1932-1939: The Prism of Unity. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976.

Endnotes

1 The historical literature on Prime Minister King is extensive. See, for example, Allan Levine, King: William Lyon Mackenzie King: A Life Guided by the Hand of Destiny (Vancouver: Douglas and McIntyre, 2011); Christopher Dummitt, Unbuttoned: A History of Mackenzie King’s Secret Life (Montreal and McGill: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2017); H. Blair Neatby, William Lyon Mackenzie King, Volume III, 1932-1939: The Prism of Unity (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1976); and J.L. Granatstein, Canada at War: Conscription, Diplomacy and Politics (Toronto: University of Toronto Press,, 2020).