6 Jean Chrétien: A Vision of Canada Through an Analysis of His Throne Speeches

A Vision of Canada Through an Analysis of His Throne Speeches

Sarah Hoag

Introduction

For the purpose of this analysis, the Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s Speech from the Throne of 1994 will be compared to his Throne Speech of 2002. This comparison will be supplemented with his response to the Reply of the Official Opposition on Leaders’ Day. In the Canadian Parliamentary system, several days are set aside to debate the Throne Speech, and on Leaders’ Day, the Leader of the Opposition normally moves an amendment to the motion to accept the Throne followed by the Prime Minister who expands on the items raised in the Throne Speech and defends the policies of his government. The Throne Speech of 1994 was a first for Jean Chrétien as Canada’s Prime Minister, and the 2002 speech was his last as Prime Minister, although the Liberal party remained in power following his retirement. Such a comparison of Chrétien’s first and last Speeches from the Throne provides an excellent lens with which to analyse Jean Chrétien’s vision of Canada over his approximately nine years in office. Though a comparison of all Throne Speeches delivered during Chrétien’s time as Prime Minister might also provide an outline of his vision for Canada, such an undertaking is beyond the scope of this paper and would merit more than a mere book chapter. In fact, such an analysis would likely require, at least, several monographs. This paper will not seek instead to analyze Chrétien’s government on the basis of fulfilling their promises outlined in two separate Throne Speeches. Of course, Political discourse changes over a Prime Minister’s tenure, necessitated by a plethora of factors such as fiscal considerations, national sentiments, global events, and many others. This paper, however, seeks only to understand the vision Jean Chrétien demonstrated for Canada by analysing his book-end Throne Speeches, the one at the beginning of his administration and the one at the end of it. As Jean Chrétien said, “A Speech from the Throne is an opportunity for the government to step back and take stock of where it is and set out the priorities for where it wants to go.”1

History and Speeches

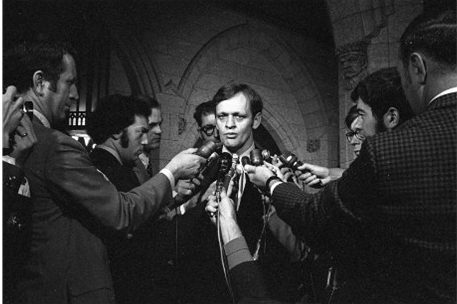

The Throne Speeches of the 35th to 37th Parliaments give insight into the Liberal party agenda for Canada in light of the 1991 shift from the Conservative leadership of Canada under Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. In many ways, the Liberal government of Jean Chrétien came into a power vacuum. Brain Mulroney, the charismatic and strong Progressive Conservative leader, had stepped down as prime minister and party leader in 1993, leaving some Canadians feeling orphaned2. Jean Chrétien, a life-long politician and Liberal, rose to power through his persistence and the unique ideas he had developed in the Liberal party under former leaders Pierre Elliot Trudeau and Lester B. Pearson. As a child and young adult, Jean Chrétien had been the subject of discrimination, classism, and reprisals.3 In comparison to other Canadian politicians of his time, Chrétien’s parents were poor which, largely, made Chrétien an outsider in elite political circles.4 It is evident in his speeches, however, that Chrétien used such a heritage and upbringing to his advantage during his political career as he was able to convince voters that he understood the class divide many Canadians struggled to overcome.

Although Chrétien was a lifelong politician, his vision for Canada also emerges from a comparison of Throne Speeches which are in reality little more than a moment in time. They provide considerable insight into his conception of Canada and they provide the primary source for this study. Those Speeches are used to support the arguments made here as well as some of the policies initiated by the Chrétien Government and the biographical materials on Chrétien that were gleamed from a variety of books and peer reviewed articles, including Iron Man by Lawrence Martin, “The Scrapper” by Nate Hendley, “A passive internationalist: Jean Chrétien and Canadian foreign policy” by Tom Keating, and others.

Stimulation of the Canadian economy was a primary pillar of the 1994 Speech from the Throne.5 Public engagement in Canadian affairs is the primary theme of the 2002 Speech from the Throne, however.6 It can be argued that the Chrétien government evolved over the course of their time in office to create a version of Canada that became cohesive and prosperous under his administration. Although a utopia can never be achieved, the list of Liberal “to dos” in 2002 was essentially a list of things they had already achieved but wanted to continue to do, but to do better, and to invest more effort and resources to keep building Canada in that direction.7 The 2002 Throne Speech painted the picture for Canadians of a government that had been working tirelessly for them and of Canadians who were working tirelessly for the nation as a collective.8 In many ways, the 2002 Speech from the Throne is an ode to Canada whereas the 1994 Speech from the Throne was an elegy for Canada that had suffered and lost its way under Conservative leadership.

Chrétien’s first remarks, by way of the Governor General, in the 1994 Speech from the Throne are not earth shaking or revolutionary by any means. An even-keel approach, driven by the request for trust in the Canadian parliamentary institution, provided the basis for the speech. It gave Canadians a sense of security that would attempt to convince them that their trust was not misplaced in electing the Chrétien Government.9 Ethic councilors were promised to bring an end to corruption, transparency was promoted, and ministers were to be held accountable by the people and to Parliament.10 Changes to the public policy formation were promised as a priority of the Chrétien government.11 Although this might seem mundane, it was a way to affirm for Canadians that policy would not be changed by Chrétien himself, but by elected officials acting in the best interests of Canada. Small businesses were targeted as essential to the financial future of Canada. It was, moreover, common knowledge that in 1994 the Chrétien Government and Canada were facing a dire financial situation. Canada was regarded by some internationally as a ‘third world debt-ridden nation’ and they mocked its financial struggles. Chrétien wanted Canadians to know that his new Liberal government wanted to educate, invest in, and support small scale Canadian businesses as he believed they would see it as a light in the darkness for many Canadians who were struggling to stay afloat. Parallels can be made back to Chrétien’s upbringing in Quebec where his parents were struggling to provide for their children.12

Chrétien understood, too, that international trade and strong, efficient Canadian industrial production were critical components for the well-being and success of Canadians and they were important elements of the Throne Speech’s emphasis on economic stimulation.13 Cultural identity was also linked to his economic plans for Canada. Although the Speech failed to elaborate on how cultural identity in Canada would not only be preserved but also help the economy but his signaling the importance of culture came as a reassurance to Canadians who feared that their cultural sovereignty was threatened by the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement that Mulroney had negotiated in 1988. Chrétien also promised a reviews on foreign policy along with celebrations of D-Day marking Canada’s contribution to the liberation of Europe during the Second World War.14 Chrétien’s last Throne speech echoed and built on his first from 1994. In essence, the 2002 Throne Speech attempted to convey a message of hope for Canada – a strategy to rebuild its economy and become a leader on the global scale through the strengthening of small business and increasing trade.

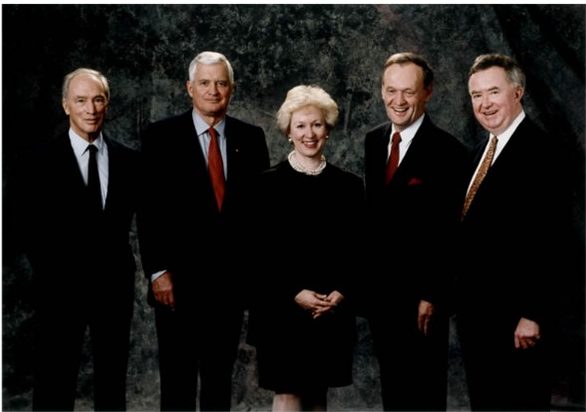

The Chrétien Government’s last Throne Speech was very different from that delivered eight years prior. Canada, as a collective, young, and prosperous nation, is presented in a positive light.15 In comparison to the dire representation of Canada in 1994, Canada was celebrated as a nation of promise. The nation he described in his speech was a force on the global scale, the Canada he shaped had become ‘Canada 2.0’ in comparison to Canada he inherited from the Conservative Government in 1994. The relationship between Canadians and the Government was the primary focus of Chrétien’s last Throne Speech.16 New issues had also emerged such as climate change and the environment and they became key features of that speech. Such a change might have become priorities of the government because the world had changed by the early 2000’s. Another important development in Canada was inter-societal relations especially between the state and Indigenous governments and the 2002 Throne Speech included greater attention on federal relations with Indigenous people in Canada.17 In terms of economic issues, they were still a priority but the 2002 Throne Speech focused on the maintenance of Canada’s strong economic position and the continuance of government diligence as a way to continue the growth the nation had witnessed since 1994.18 Canada’s involvement in the United Nations and other international organizations was also a primary element of the 2002 Throne Speech, along with the events of 9/11 as part of a recapturing the Government’s commitment to its people and to world peace.19 The government had looked to the people of Canada for input on Canada’s role in the world. The first Throne Speech in 1994 had not taken direct measures to involve the Canadian public in these matters.20

Over the decade the government had matured and grown more confident and this is evident in the 2002 Throne Speech. While the 1994 Throne Speech dripped with the rhetoric of saving Canada and dealing with a crushing fiscal reality, the 2004 Throne Speech turned optimistic and pointed to a rebuilding of Canada. As such, the healthcare system in Canada became another major focal point of the 2002 Throne Speech as an essential element of creating a caring and compassionate nation. This was also demonstrated in support for lower income families and children which became a priority of the 2002 Throne Speech. It seems that the Throne Speech became a vehicle for Chrétien to reiterate for Canadians that the Liberals had secured Canada financially throughout their three mandates and they now could re-invest in social programs and build on the legacy of past Liberal governments that had created Canada’s welfare state.21 In both Speeches from the Throne unity was an important issue as it is with all governments in Canada. While the foreign policy of Jean Chrétien had not been well outlined in the Throne Speech of 1994, in the Speech of 2002 Chrétien makes an effort to identify the impacts of 9/11 on Canada and Canada’s involvement in organizations such as the United Nations.22 Keating notes, however, that, “[…] as Prime Minister he seemed to have a limited interest in these areas, a more modest view of the country’s role and, not unimportantly, a strong belief in the greater importance of domestic affairs.”23 Jean Chrétien really was concerned with Canada domestic affairs, and he made no effort to hide his desires to hoist Canada out from under its massive debt, heal the national divisions, and build a new social Canada Let us now turn to each of the Throne Speeches. Analysing the Throne Speeches through a comparative lens allows us to explore the bold vision Chrétien had for Canada. It was one of restoring economic prosperity, building regional cohesiveness, and growing for the future. By comparing his Speeches in 1994 and 2002, we can see how one prime minister inherited a nation and how he became proud of the Canada he shaped and how he believe his vision at the end of his career as Prime Minister would continue to shape the nation.

Throne Speech 1994

Context matters. To understand Prime Minister Jean Chrétien’s framework and concepts of the Speech from the Throne and his Leaders’ Day reply we must recall the 1994 election. The Liberal party had lost in the two previous federal elections against the Conservative Party led by Brian Mulroney.24 These defeats, including the poorest showing ever by the Liberals, would make the elections of 1993 even more important as to re-establish the Liberal party’s power as the governing party in Canada. Lawrence Martin once wrote, “[the] Liberals were impatient in their lust for a new leader.”25 Canada had been through a decade of Conservative Governments, the Liberals had been through years of defeat, and a new leader seemed to be their way to generate momentum for the 1993 election and regain power. Chrétien emerged as one of the favorite of Liberals across Canada, capturing the leadership of the Liberal Party in June 1990 and winning a majority government in 1993.

The Throne Speech of 1994 was the Liberal party’s opportunity to set the tone of their government for the next four years. Critics of the 1994 Throne Speech, following the election of the Liberal party, said the speech “set modest aims”.26Prior to be elected Prime Minister, Chrétien is noted to have said, “I came back into politics for one reason: I want Canada to stay together [… and]” he then added, “[…] we have become more British Columbian, more Albertan, more Québécois, and more Ontarian. This is a problem. We have to become Canadian. Otherwise we won’t survive.”27 These ideas were echoed in his response on Leaders’ Day in 1994 when he said, “We are French Canadians […] our country is Canada.”28 Although national unity and the ending of the fragmentation of Canada had been priorities of Chrétien though his career in federal politics and certainly during his time as Prime Minister, these sentiments of healing a fractured Canada were not front and centre in his first Speech from the Throne. During the 1994 Speech, a view of Canada being united by a strong government was clearly the dominant narrative. The government Jean Chrétien envisioned for Canada was one that provided opportunity for Canadians to achieve their full potential, while maintaining and promoting Canadian unity.29 In his response to the opposition leader on Leaders’ Day in 1994, Chrétien discussed his meetings with the provincial leaders where he advocated for more open trade among the provinces.30 Trade, it seems, was a means of promoting national unity.

Newspapers such as the Globe and Mail claimed that the Liberal Speech from the Throne of 1994 “set modest goals” and that it was a “repackaged version of the party’s […] promises from the fall election campaign”.31 These claims were echoed by the Leader Post which said that, “[t]he speech read like a condensed version of the red book on policy the party used during the campaign last fall.” 32 Though these comments were critical of the 1994 Throne Speech, they provided a sense of Liberal certainty that what they had campaigned on was what they plan to accomplish while holding office. The Throne Speech did not introduce new ideas to the Canadian populace about the Liberal agenda, yet it did attempt to put at ease a fractured nation. For these reasons, national unity was a primary message of Jean Chrétien’s Speech from the Throne. The speech, by tradition, was delivered by the Governor General. The Speech from the Throne of 1994 was less about the policies the Canadian government would enforce and more about Canadian identity.33 In his short speech, Chrétien used the word “Canadian” over twenty times.34

The 1994 reply to the Speech from the Throne was delivered by the Honourable Lucien Bouchard, the official leader of the opposition and leader of the Bloc Québécois, a federal political party devoted to Quebec sovereignty.35 Bouchard’s Reply begins by noting that the Official Opposition was elected by the people of Quebec and new representations in Western Canada.36 He then goes on to address the upcoming referendum in Quebec and the opposition’s representation of Quebecois sovereigntists. Mr. Bouchard then goes on to address the differences between Quebec and what he calls, “English Canada”.37 He is clear in his response, English Canada will no longer dominate political discourse at the federal level. In some ways, his response targets Chrétien personally as Mr. Bouchard quotes General Charles de Gaulle who compared the uncertainties of longing to the truth of reality.38 Jean Chrétien’s long political career meant that he had been a politician during the time when the French President Gaulle and the Canadian Prime Minister Lester B. Pearson were in dispute.39 This response draws attention to what Jean Chrétien didn’t say in his Speech from the Throne as much as what he did say. The rebuttals to the Throne Speech address issues of economic uncertainty in Canada unemployment rates, Canadian foreign affairs, federalism, Quebec-Canada dualisms, and federal spending. 40 He states, “This partnership [economic] will also extend to our work in knitting together a stronger social fabric in Canada.”41 After the Leader of the Opposition’s remarks and his comments on Canada’s dual national identity, the Prime Minister has the opportunity to respond.42 Jean Chrétien mentioned Quebec only when discussing the issue of Atlantic fisheries.43 He did not mention French and English relationships in Canada as being divergent nor did he suggest that national unity was in peril (despite the recent defeat of the Meech Lake and Charlottetown Accords to “bring” Quebec into the Constitution).44 Jean Chrétien does however say that, “Our cultural heritage and our official languages are at the very core of the Canadian identity and are sources of social and economic enrichment.”45 These words of unity paint a picture of Canada that is far from the one described by the Honourable Lucien Bouchard. It is evident in the 1994 Speech from the Throne and Leader’s Day remarks by Jean Chrétien that Canada is to be a nation united on all fronts and that discussions of Quebecois separatism was not to be on the table for discussion.

Jean Chrétien’s response to Mr. Bouchard’s reply to the Throne Speech was quite lengthy. After his congratulatory messages to the Speaker of the House and other members of Parliament, the Honourable Jean Chrétien calls Canada a, “great work in progress” indicating his vision of Canada to be one greater than the Canada left behind by the Conservative Government before him.46 He speaks of the people in his own constituency who wish for healing in Canada – a message distinct from that delivered by Bouchard who was intent on achieving Quebec sovereignty and effectively sundering the Canadian nation.47 The vision of a united Canada Jean Chrétien outlined in his Speech from the Throne were ones of unity yet, Bouchard’s reply to Chretien suggests Canada is a country with clear divides. Perhaps Jean Chrétien saw his Throne Speech as a way of implementing a vision of Canada under a Liberal government that would heal the divisions through a series of new policies and approaches to governing whereas Bouchard saw Canada so mired in crisis that opting out was the only option for Quebec. Chrétien’s approach to the question of unity can be supported by his remark, “Everything we do during this Parliament will be aimed at healing the deep wounds in our country, at restoring the bonds of trust and respect between Canadians and the government.”48 The wounds he is most likely referring to are the economic and cultural wounds in Canada. In 1994, Canada was facing an economic crisis. His vision of Canada is further outlined when he discusses how his government was dealing with Canada’s desperate economic situation. For example, the Chrétien government cut funding for the “helicopter program”, the Pearson airport, and to the appointment of more ministers.49 These cuts showed Canadians that the government was prepared to sacrifice luxury for the benefit of Canadian taxpayers. If every day Canadians could not live in security, nor would the government.

Throne Speech 2002

In response to the 2002 Speech from the Throne, Jean Chrétien spoke in memory of Canadian politician and diplomat Ron Duhamel.50 These remarks of remembrance initiated a conversation on Francophone representation outside of Quebec as Mr. Duhamel was Canada’s representative in La Francophonie as well as a Franco-Manitoban.51 Chrétien takes a different approach in the 2002 Leaders’ Day address as he says his Throne Speech was a way to spark meaningful debate in the House of Commons and a way for the Government to evaluate itself on how they are governing.52 The Speech from the Throne of 2002 was an entirely different story. With the Liberal Government as the incumbent party of nearly 9 years, the Canadian populace knew the face of Jean Chrétien well. This was not a Throne Speech directly following a federal election, nor was it a speech written by a new leader. The Throne Speech of 2002 was unique for a different reason, it was Jean Chrétien’s last Throne Speech to prove his competence as a leader. For the governing Liberal party, issues of leadership and who held the torch of authority was in the back of every member’s mind. The Liberal Government, and their affiliations, were under fire of accusations by the press and internal associates.53 The 2002 Speech from the Throne was important to Chrétien and the Liberal party for reasons different from those of the 1994 Speech from the Throne. In 2002, Chrétien had something to prove, the Liberals had face to save, and North America was still feeling the devastating effects of 9/11, which occurred only one year prior.54’55 Jean Chrétien reportedly promised to deliver on all his promises prior to his retirement, only a year and some months away from the 2002 Throne Speech.56 For this reason, the Throne Speech of 2002 and the one of 1994 can be used as perfect examples of comparison. Jean Chrétien, in both speeches, wanted Canada to unite under him without a divide of language, class, or other dividing factor. To reinforce Chrétien’s views of unity in Canada, he notes that the goal of the government is to “minimizing divisiveness” in order to improve Canada.57

The topics of Chrétien’s Leaders’ Day address demonstrate his pride in what his government has accomplished. He even uses the word “proud” when discussing the ways in which the Liberal party dealt with lowering taxes for Canadians.58 All in all, Jean Chrétien wanted, so badly, for Canada to break down its barriers of separation. Chretien wanted Canadians to unite under his government, no matter if their barriers of division were those of provincial boundaries, education, class, access to resources, or culture.

Conclusion

As Prime Minister Jean Chrétien focused on Canada and fixing the perceived internal divides that he saw in Canada. Many Canadians dream of becoming Prime Minister and many certainly think they could do a better job than a sitting Prime Minister. The role of a Prime Minister, most agree, is to direct and guide Canada, speak on its behalf, and shape Canada. As Prime Minister Jean Chrétien was a nationalist. He believed in the power of unity under the Canadian flag. His foreign policies were weak and his acknowledgement of the Quebecois separatist movements was lacking, but through two Throne Speeches considered here, he stressed the importance of economic and fiscal security as a means of creating security for Canadians and he helped Canadians envision a Canada that would provide for future generations.

Bibliography

Bosher, J. F. The Gaullist Attack on Canada, 1967-1997. Montréal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1999.

Chrétien, Jean. del. by Adrienne Clarkson. “Speech from the Throne to open the Second Session

Thirty-Seventh Parliament of Canada.” Parlinfo. Parliament of Canada, September 30, 2002. https://lop.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/Parliament/procedure/throneSpeech/speech372.

Chrétien, Jean. del. by Ray Hnatyshyn. “Speech from the Throne to Open the First Session

Thirty-Fifth Parliament of Canada.” Parlinfo. Parliament of Canada, January 18, 1994. https://lop.parl.ca/sites/ParlInfo/default/en_CA/Parliament/procedure/throneSpeech/speech351.

Chrétien, Jean. “Jean Chrétien on Speech From The Throne.” openparliament.ca, January 19, 1994. https://openparliament.ca/debates/1994/1/19/jean-chretien-7/only/.

Chrétien, Jean. “Speech From the Throne.” Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Edited Hansard. (35th Parliament, 1st session,). January 19, 1994, Retrieved from LiPaD: The Linked Parliamentary Data Project website: https://lipad.ca/full/1994/01/19/7/.

Chrétien, Jean. “Speech From the Throne.” Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Edited Hansard. (35th Parliament, 1st session,). January 19, 1994, Retrieved from LiPaD: The Linked Parliamentary Data Project website: https://lipad.ca/full/1994/01/19/6/#3952392.

Chrétien, Jean. “Speech From the Throne.” Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Edited Hansard. (37th Parliament, 2nd session,). October 1, 2002, Retrieved from LiPaD: The Linked Parliamentary Data Project website: https://www.lipad.ca/full/2002/10/01/1/

Delacourt, Susan. 1994. “Throne Speech Sets Modest Goals: Liberals to Act on Promises of Job Creation, Integrity, End to GST.” The Globe and Mail (1936-2017), Jan 19, 2. https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.uregina.ca/historical-newspapers/throne-speech-sets-modest-goals/docview/1143575753/se-2?accountid=13480.

Greenshields, Vern and Dave Traynor in the Leader-Star Services “Grits Vow Integrity, Economic Growth.” The Leader Post (1930-2010), Jan 19, 1994. https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.uregina.ca/historical-newspapers/january-19-1994-page-1-32/docview/2214442582/se-2?accountid=13480.

Hendley, Nate and Gabriel Morrissette. Jean Chrétien: The Scrapper Who Climbed His Way to the Top. Toronto: Jackfruit Press, 2005.

Johnson, William. “Time to Remember an Old Promise, Mr. Chrétien: PIT BILL.” The Globe and Mail (1936-2017), (Sep 19, 2002) 1. https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.uregina.ca/historical-newspapers/time-remember-old-promise-mr-Chrétien/docview/1356842909/se-2?accountid=13480.

Keating, Tom. “A passive internationalist: Jean Chrétien and Canadian foreign policy.” Review of Constitutional Studies, (January-July 2004), Gale Academic OneFile Select, https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A208452484/EAIM?u=ureginalib&sid=EAIM&xid=4b7803ed.

Lucien Bouchard, “Speech From the Throne.” Canada. Parliament. House of Commons. Edited Hansard. (35th Parliament, 1st session, January 19, 1994), Retrieved from LiPaD: The Linked Parliamentary Data Project website: https://lipad.ca/full/1994/01/19/6/#3952392.

Martin, Lawrence. Iron Man: The Defiant Reign of Jean Chrétien. Toronto: Viking Canada, 2003.

McCarthy, Shawn. . “Chrétien’s Desire to Execute Agenda Faces Tough Tests.” The Globe and Mail (1936-2017), (Sep 28, 2002) 1. https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.uregina.ca/historical-newspapers/Chrétiens-desire-execute-agenda-faces-tough-tests/docview/1366109623/se-2?accountid=13480.

Gibbins, Roger. “For Better Or Worse, His Legacy Will Last.” The Globe and Mail (1936-2017), Feb 25, 1993. https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.uregina.ca/historical-newspapers/better-worse-his-legacy-will-last/docview/1143739189/se-2?accountid=13480.

Simpson, Jeffrey. “Jean Chrétien’s Only Agenda: ‘I’m in Charge here’: THE NATION.” The Globe and Mail (1936-2017), (May 04, 2002). 1. https://login.libproxy.uregina.ca:8443/login?url=https://www-proquest-com.libproxy.uregina.ca/historical-newspapers/jean-Chrétiens-only-agenda-im-charge-here/docview/1356973513/se-2?accountid=13480.