4 The Role of Nurse Leaders in the Development of the Canadian Health Care System

Nurses interact every day with Canadians seeking assistance to maintain and improve their health. As a result, nurses can identify trends in population and public health. They know the strengths and the weaknesses of Canada’s health system. They see, first hand, the issues related to accessibility of services. Nurses witness the need to integrate health services with other aspects of social development policy. They work with change in the form of emerging research, knowledge and new technology.

—CNA presentation to the Senate Standing Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology (Calnan & Lemire Rodger, 2002)

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) set 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) for world health in 2015. These 17 SDGs include human activities across the economic, social, and environmental dimensions of health. Dr. Margaret Chan, Director-General of the WHO, stressed that universal health coverage (UHC) is the “linchpin of the health development agenda, not only underpinning a more sustainable approach to the achievement of the other health targets, but allowing for a balance between them” (WHO, 2015, p. iii). UHC is regarded, at an international level, as a “tested and proven” framework that guides progressive health care transformation within individual countries. Canada pioneered UHC for the world. This chapter will trace the role of nurse leaders in the development and provision of health care in Canada from the time of the first settlers through to the development, implementation, and ongoing refinement of UHC. The chapter will also include a brief overview of demographic and social forces that exerted a significant impact on both nursing leadership and the Canadian health care system.

Much of the historical information within this chapter is based upon the Canadian Nurses Association (CNA) history book, One Hundred Years of Service (CNA, 2013). For a more detailed account of the historical role of Canadian nurse leaders, you can access the full book here.

Learning Objectives

- Review historical events related to Canadian health care and the role of early nurse leaders in those events.

- Identify how health care responsibilities have been divided among federal, provincial, and territorial governments.

- Describe how demographic forces and social forces impact nurse leadership within the Canadian health care system.

4.1 Early Nurse Leaders in Canadian Health Care

Nurses have played an important role in the health of Canadians for over 400 years. The history of nursing in Canada began with Marie Rollet Hébert, the wife of an apothecary from Europe who settled in what is now Quebec City. She assisted her husband in providing care for the early settlers from 1617 until her death in 1649. Gregory and colleagues describe how she consulted with Indigenous peoples regarding healing methods (Gregory, Raymond-Seniuk, Patrick, & Stephen, 2015). They also recount how she educated Indigenous children and quickly became known as “Canada’s first teacher.”

The first Hôtel-Dieu in New France, still in existence today, was established in 1639 by three sisters of Augustines de la Miséricorde de Jésus in Quebec City to care for both the spiritual and physical needs of their patients. Jeanne Mance, known as Canada’s first lay nurse (CNA, 2013), had both medical and surgical skills. She arrived on Montreal Island from France in 1642 and established a hospital the following year (Gregory et al., 2015). In 1659, she recruited three sisters from the Hospital Sisters of Saint-Joseph in France to assist with running the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal (Noel, 2008). She is credited with co-founding the city of Montreal.

The founding of the Hudson’s Bay Company accelerated the growth of commerce and trade between the Europeans and the Indigenous population of Canada. However, the Europeans brought much more than traders, settlers, and education to Canada. During the seventeenth century, a small pox epidemic killed almost half of the Huron people (CNA, 2013) and the services of the European lay nurses were in great demand.

In 1747, Marie-Marguerite (Dufrost de Lajemmarais) d’Youville led a lay group of women to take charge of the bankrupt Hôpital Général de Montréal. They turned it into a hospice for aged men and women, orphans, and “fallen” women. This group of women became known as the Grey Nuns in 1755 (Jaenen, 2008). Marie-Marguerite d’Youville was the first Canadian to be canonized and was named a saint in 1990 (CNA, 2013).

The nineteenth century was a time of rapid advances in both health care and nursing education. Almost concurrently with the publication of Florence Nightingale’s Notes on Nursing in 1859, Louis Pasteur published a paper suggesting that human and animal diseases are caused by micro-organisms (CNA, 2013). Canadian nursing expertise grew rapidly as the first graduates from the Nightingale Training School began working in 1865 and the first Canadian graduates from the Mack Training School for Nurses started working in 1878. The first two professional male nurses in Canada graduated from the Victoria General Hospital School of Nursing (Halifax) in 1892 (CNA, 2013).

Rapid changes to the North American frontier also took place during the nineteenth century. The British North America Act formally established the Dominion of Canada, composed of Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick, with John A. Macdonald elected as the first prime minister in 1867. Between the years of 1870 and 1898, Manitoba, British Columbia, Prince Edward Island, the Northwest Territories, and the Yukon Territory joined Canada. The completion of Canada’s first transcontinental railway in 1885 linked these vast expanses of land together as one country and brought settlers into the open lands of the west.

The rapid opening of the Canadian west to settlement brought to light a shortage of health care providers and hospitals in the isolated western communities. Lady Ishbel Aberdeen, wife of Canada’s Governor General, wrote about the “pathetic stories” she heard, “where young mothers and children had died, whilst husbands and fathers were traveling many weary miles for the medical and nursing aid, which might have saved them” (VON Canada, 2017). Lady Aberdeen was asked by the National Council of Women to establish an order of visiting nurses to travel to areas without medical or health services and establish small “cottage” hospitals. This order of nurses was to be founded in honour of the sixtieth anniversary of Queen Victoria’s ascent to the throne. Amazingly, parliamentary support for the order wavered because of opposition from Canadian doctors.

However, Lady Aberdeen accepted the challenge and, despite resistance, The Victorian Order of Nurses (VON) was established in late 1897, with Lady Aberdeen the inaugural president.

Figure 4.1.1 Lady Aberdeen Established VON to Provide Health Services in Rural and Remote Communities

The VON’s first tasks included the provision of visiting nursing services to areas without medical facilities and the establishment of small “cottage” hospitals in isolated areas of the west. The VON Canada nurses were immediately dispersed to rural and remote areas across Canada. In 1898, four VON Canada nurses travelled with military and government officials to the Klondike in the Yukon where during the gold rush many prospectors were suffering from a typhoid epidemic. VON Canada sites were opened in Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto, Halifax, and Kingston, and the first “cottage” hospital was established in Regina to care for the early prairie settlers.

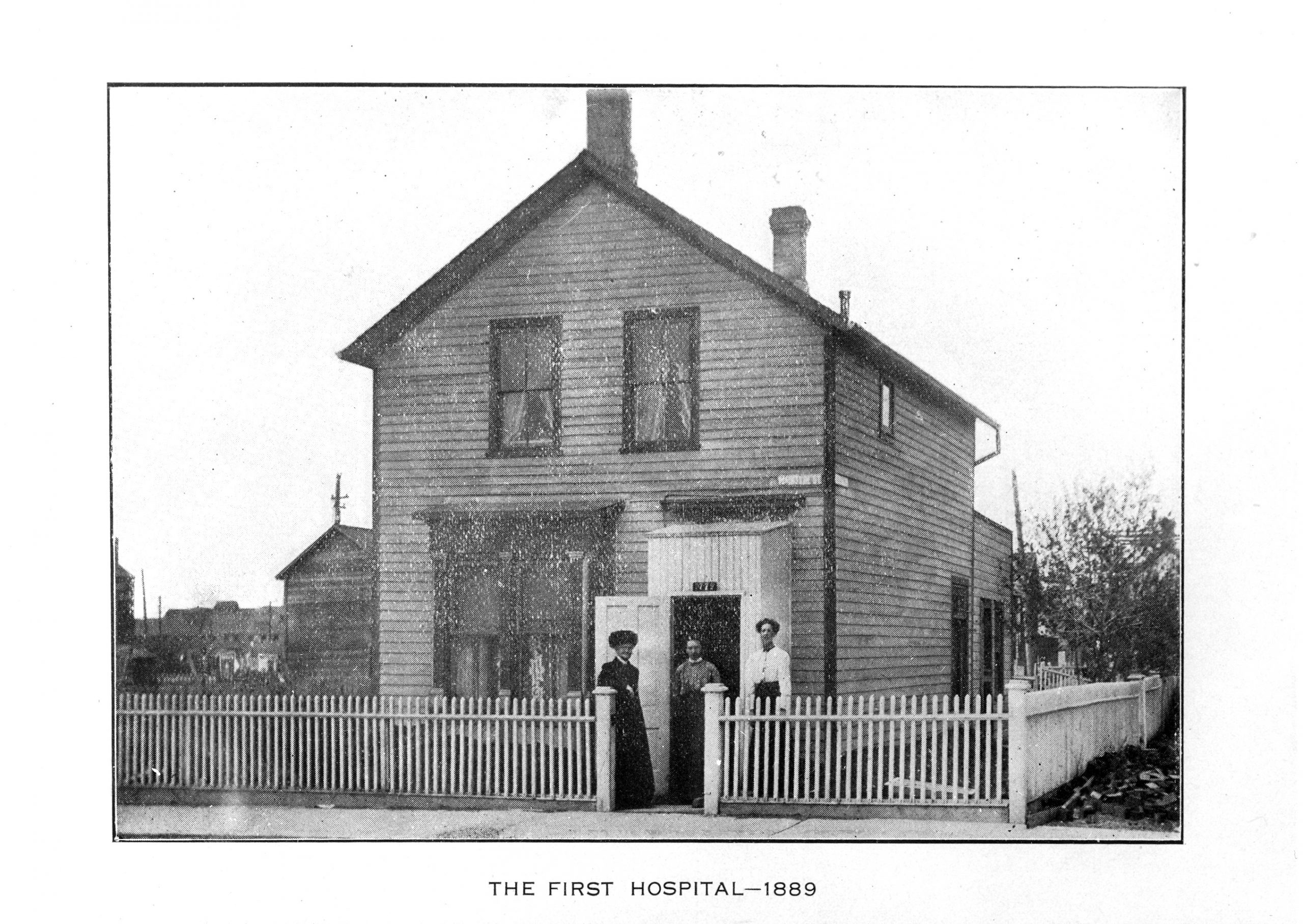

Figure 4.1.2 The First Hospital in Regina, Saskatchewan

Essential Learning Activity 4.1.1

For further insight into the response of physicians to the establishment of the VON, watch this short Heritage Minutes video on “Cottage Hospitals” (2:00), produced by Historica Canada.

4.2 Health Care and Nursing Highlights of the First Half of the Twentieth Century

The early years of the twentieth century saw the establishment of 43 additional VON hospitals in rural and isolated areas of Canada. The VON services were funded through community fundraising led by prominent community members such as Lady Minto (the wife of another Canadian Governor General). The responsibility for running these hospitals was eventually placed in the hands of the communities, with the last VON Canada–run hospital handed over to the community in 1924. However, VON nurses have remained involved with community nursing to the present day.

In good times and bad, VON Canada served as a catalyst for building a sense of community—creating opportunities for people to work together to meet their needs and those of friends and neighbours. Prenatal education, well baby clinics, school health services, visiting nurses, and coordinated home care programs all had their earliest origins with VON Canada (VON Canada, 2017).

The establishment of the International Council of Nurses in 1899 and the service of Canadian troops in the Boer War in South Africa heralded an increased Canadian nursing involvement in international affairs. Canadian nurses left their mark in the Boer War as Georgina Fane Pope was the first Canadian awarded the Royal Red Cross for her extraordinary service as a nurse in the Boer War.

The Canadian Nurse journal was first published in 1905. The intention of the journal was to “unite and uplift the profession, and protect the public through work such as advocacy for nurse registration legislation” (CNA, 2013, p. 203). Journal articles dealt with issues similar to those that we continue to deal with today. One early article, a discussion on patient safety in the operating room, reported that a pair of forceps had been left in a patient, and the author made a recommendation that “forceps should be counted in operating rooms” (CNA, 2013, p. 203). The author of another article noted that “Canadian nurses are highly valued abroad” (CNA, 2013, p. 204) and she despaired that 50 to 75 per cent of graduate nurses from smaller Ontario cities had moved to the United States to work. As early as 1907, the editor of the Canadian Nurse was requesting “improved hours of work, workload and general working conditions for nurses” (CNA, 2013, p. 204).

This growing concern for patient safety and the need for an organized nursing voice led to the establishment of the Canadian National Association of Trained Nurses, which eventually became the Canadian Nurses Association, in 1908. Mary Agnes Snively was the founding president of the organization. In addition, by 1914, all existing provinces except Prince Edward Island had their own provincial nursing associations. By 1922, all nine existing provinces had some form of nursing registration legislation.

World War I began in 1914. Approximately 2,000 “trained Canadian nurses, with 27 matrons and a reserve of 203 for special hospital service were enlisted” (“The War Years,” 2005, p. 39). Nurses were eager to volunteer to serve in the armed forces. “For example, when a call was made in January 1915 to fill 75 positions, 2,000 nurses applied” (”The First World War’s Nursing Sisters,” 2016, p. 17). Nurses in the Canadian army received a higher income than the enlisted men and were accorded authority as a lieutenant. Lieutenant Colonel (retired) Harriet (Hallie) Sloan further explains the reasons for this rush of nurses to enlist:

From the time of the Boer War, Canadian nurses had officer status, with the same rank, pay and privileges of army lieutenant. They also had the power of command over those working under them, such as orderlies. . . . Among the Allied forces in both world wars, Canadian nurses were the only ones to enjoy equality with officers. (“The War Years,” 2005, p. 39)

Canadian nurse Margaret MacDonald, appointed matron-in-chief of the Canadian army nursing service, was the first woman given the rank of major in the British Empire, while medals or decorations were awarded to 660 Canadian nurses. However, in addition to the many positive aspects of nursing service in the military, 47 Canadian nurses lost their lives in World War I (CNA, 2013).

Essential Learning Activity 4.2.1

To find out more about military nurses in World War I, watch this short Heritage Minutes video called “Nursing Sisters” (1:00).

World War I, combined with the Spanish Flu epidemic (1918–mid-1920s), hit healthy young adults hard and left many nurses as the sole supporters of their families. In addition, the stock market crash of 1929 started the Great Depression, leading to further hardships. Hospital nursing work was difficult to find and since private duty nursing was more abundant and offered shorter hours and better pay than hospital nursing, many nurses worked private duty (CNA, 2013). However, overall poor pay and scarcity of work culminated in deprivation for countless nurses and their dependents throughout this time period.

World War II started in 1939 and over 4,000 nurses enlisted. Many enlisted because they would be assured of a good wage. Their services were greatly appreciated by the soldiers, as Pauline Siddons describes: “I have memories of halls lined with stretcher patients waiting for a bed, while more loaded ambulances continued to arrive” (Bassendowski, 2012, p. 91).

Figure 4.2.1 Historical Picture of Nurses Leading Disaster Response

Military service provided independent decision-making opportunities for Canadian nurses and prepared them for future leadership positions. One nursing veteran recalls:

It was during this bloody war that one learned and dared to be a nurse of the future. As nursing sisters in front line units, we gave intramuscular injections, administered intravenous solutions . . . removed sutures, did major dressings. . . . On our way to Italy . . . malaria added greatly to our workload. We learned to do blood smears, determine from all our findings the type of disease, and initiate intravenous treatment where indicated. (Pepper, 2015, p. 8)

Thirteen Canadian nursing sisters lost their lives in World War II.

During World War II, a severe shortage of trained civilian nurses led to a search for a new source of nursing personnel within the hospitals. The CNA advised the provinces to develop a course for nursing assistants. To support the provinces in this pursuit, the CNA developed the first curriculum for nursing assistants in 1940.

Recommendations coming from a 1943 National Health Survey focused on providing salaries and working conditions for nurses “comparable to those prevailing in other occupations requiring similar preparation” (CNA, 2013, p. 218). However, hospitals were “unable or unwilling to capitalize on nursing sisters’ demonstrated abilities in expanded technological roles or their increased autonomy. Instead, hospitals relied heavily on student labour, with limited roles for ‘specially trained’ graduate nurses” (Toman, 2007, p. 202). Upon return to civilian life following the end of World War II, most nursing sisters resisted conventional hospital roles and sought alternate careers. The following statement from Mary Tweddell helps explain the dilemma of the nursing sisters: “We’d been living the army life—I’d been four years over there—and it was a different life entirely. You came back here and you’d be amazed how hard it was to get back” (Bassendowski, 2012, p. 48).

4.3 Health Care and Nursing Highlights of the Second Half of the Twentieth Century

During the decades following World War II, access to health care became a Canadian public priority. However, the nursing shortage continued. Increased responsibilities and poor working conditions in hospitals led nurses to demonstrate an interest in collective bargaining. The first nursing union was formed in British Columbia in 1945.

The 1948 federal grants program offered money for health surveys, public health research, infectious disease control, and grants for hospital construction (when matched with provincial funding). The building of new hospitals created a further shortage of health care personnel. Nursing schools could not graduate registered nurses in adequate numbers to meet the demands. Auxiliary workers, such as nursing assistants, were hired by hospitals to assist the RNs.

Universal Health Care Coverage

Public apprehension about access to health care dominated the Canadian health care landscape for the last half of the twentieth century. The first Canadian health region was established in Swift Current in 1946. For less than $20 per person per year, residents received “doctor services, hospitalization, children’s dental care, and a professional public health service including nurse, immunization programs and health inspectors” (Matthews, 2006, para 3).

Two of the significant outcomes of this “experiment” were (1) an increase in doctors in the Swift Current Health Region from 19 in 1946 to 36 in 1948; and (2) as a direct result of the work of the nurses and access to doctors, a drop in the infant mortality rate to the lowest in Saskatchewan. The Saskatchewan Medicare system, based on the Swift Current model, was introduced to the entire province of Saskatchewan in 1962. The Swift Current Health Region, the first universal hospital and medical care program in North America, was a harbinger of international health care priorities in the twenty-first century (WHO, 2017).

Essential Learning Activity 4.3.1

Saskatchewan nurses have been very involved in the Canadian health care system. To find out more about the history of nursing in Saskatchewan, watch this video titled “The Role of Canadian Nurses during WW1 & WW2” (5:19) by Dr. Sandra Bassendowski, Professor, College of Nursing, University of Saskatchewan.

The introduction of UHC coverage to Canadians was a multi-step process, commencing with the passing of the national Hospital Insurance and Diagnostic Services Act (1957), which covered the cost of inpatient treatment, laboratory services, and radiology diagnostic services in acute care hospitals throughout Canada. In 1966, the Medical Care Act extended health coverage for Canadians to help cover the costs of physicians’ services outside hospitals. Canada’s national health insurance program was structured to ensure that every Canadian received medical care and hospital treatment, which was paid for by taxes or compulsory health insurance premiums. Costs were shared between the federal and provincial governments, providing the provinces met the principles of accessibility, universality, comprehensiveness, portability, and administration (CNA, 2013; Dunlop, 2006).

Health care costs spiralled after the implementation of Medicare, and a review of the publicly funded insurance programs was conducted in 1979 by Justice Emmett Matthew Hall. Dr. Helen Mussallem, then executive director of the CNA (and a World War II veteran), presented the CNA’s brief, “Putting Health Back into Health Care” to the review. This document highlighted the CNA’s belief that:

insured health-care services should be extended to include more than just acute care, that nursing services should be covered and serve as an entry point to the health-care system and that all extra premiums such as extra-billing and user fees should be banned. (CNA, 2013, p. 105)

Dr. Ginette Lemire Rodger assumed the position of executive director of the CNA following Dr. Mussallem’s retirement in 1981. Dr. Lemire Rodger conducted extensive lobbying to support the recommendations set out in “Putting Health Back into Health Care.” The Canada Health Act passed in 1984 included several of the revisions recommended by the CNA. Nursing leaders, including Dr. Lemire Rodger and Dr. Helen Preston Glass (CNA president) had been “unable to convince parliamentarians to extend coverage to services outside hospitals and other medical institutions, but they did manage to have the description of potential providers of insured services broadened to include health-care practitioners and not just physicians” (CNA, 2013, p. 106). Opening the door to funding of insured nursing services was the catalyst that promoted the presence of nurse practitioners in outpatient and nursing clinics.

Essential Learning Activity 4.3.2

Answer the following questions as you review the Canada Health Act:

- What are the five standards that the provinces and territories must meet?

- What are the responsibilities of the provinces and territories for health care?

- What services do the provinces and territories fund?

- What are the responsibilities of the federal government for health care?

- What services does the federal government fund?

- How does the federal government fund and work with First Nations and Inuit people?

To understand more about health care services for First Nations and Inuit people, visit the First Nations and Inuit Health web page on the Health Canada website. Then answer the following questions:

- What is Jordan’s principle?

- If a First Nations child is not receiving services and supports, who is to be contacted?

Auxiliary Workers

The federal government’s plan provided grants that were to be matched by provincial money and provided momentum for rapid hospital construction and renovation. By 1950, money had been approved for almost 20,000 additional hospital beds throughout Canada. These grants, combined with other state-sponsored health focused programs, increased the public’s demand for health care. A new category of auxiliary workers was introduced to meet these demands. The CNA was supportive of these auxiliary workers, having already developed a curriculum for nursing assistants in 1940. The provinces began to create courses and bring the licensing of this new classification of auxiliary workers under their control.

Nursing Education

Figure 4.3.1 First Graduating Class from the University of Saskatchewan, 1943

Nursing education was a focus of Canadian nurse leaders for the last half of the twentieth century. Nursing students had become indispensable care providers for patients within the hospitals and were frequently overworked by the hospital administration. Nurse leaders became increasingly alarmed about the quality of education provided to these students who learned on the job by providing much of the patient care. In 1946, Evelyn Mallory, president of the Registered Nurses Association of British Columbia questioned the state of nursing education:

Are we going to continue to compromise, to muddle along with nursing education and nursing service hopelessly confused, not only in the minds of the public, but in the minds of nurses as well, as has been the case for years? Or were nurses at long last going to do some really constructive planning in relation to the preparation of professional nurses, frankly recognizing that we must have more nurses and better nurses if the needs of the community are to be met? (cited in CNA, 2013, p. 72)

In an attempt to improve the education of nurses, the CNA piloted an accreditation program for schools of nursing. The 1960 pilot accreditation project report on the Evaluation of Schools of Nursing revealed that 21 out of 25 schools failed to meet the standards. As stated by Dr. Helen Mussallem, “the students were not students, they were indentured labour” (CNA, 2013, p. 81).

Dr. Mussallem was the first Canadian nurse to complete a PhD in nursing. Her research, which focused on the development of nursing education in general educational systems, received extensive attention from both professionals and the general public. She recommended a complete revision of Canada’s nursing education system. Following publication of her research, the Globe and Mail described nursing training in the following words:

The hospital system of training nurses is closely akin to the army system of training soldiers . . . that deprives her of some of her civil rights—she must submit to curfews, to a considerable control of her leisure time, even to dictates about her personal grooming . . . and not even be able to insist on the most basic of rights—the right to be treated as a reasonable, responsible adult in a free society. (CNA, 2013, p. 85)

Dr. Mussallem’s research brought the need for a change in nursing education to the forefront of Canadian nursing and served as a catalyst for the movement of nursing education out of the hospitals and into Canadian colleges and universities.

Figure 4.3.2 Saskatchewan Collaborative Bachelor of Science in Nursing (SCBScN)

Nursing Research

Nursing leader Dr. Ginette Lemire Rodger fought against strong gender, age, occupational, and academic prejudices within the Medical Research Council (now the Canadian Institutes of Health Research) when she joined the council in 1986 and worked to move research funding beyond bench scientists and physicians. Due to her persistence, financial support was found for both nursing research and nursing research infrastructure. Linked to this awareness of the need for nursing research, the first fully funded PhD program was opened at the University of Alberta in 1991. Dr. Lemire Rodger soon became the first graduate from a Canadian nursing PhD program. As Canadian nurses acquired the university graduate credentials required for teaching and research, they began to develop a unique body of Canadian research centred upon the discipline of nursing.

Research Note

Northern Saskatchewan is home to many Indigenous people, who live in small, often isolated, settlements. The economic conditions in the north were abysmal during the twentieth century. The first nursing stations were established in Ile-a-la-Crosse in 1927 and Cumberland House in 1929. Nursing was the backbone of health care in the North.

Following the 1944 election of the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in Saskatchewan, an emphasis was placed on “integration of the underprivileged of society” (McBain, 2015). This initiative was funded by taking advantage of wealth generated through the exploitation of abundant natural resources, such as uranium, found in this region. Nine additional nursing stations were established between 1941 and 1955. Only two of these stations were federal—those in Lac La Ronge and Pelican Narrows. Because small settlements were scattered across the North, it was difficult to develop the resources required to provide good medical care in the local communities. Consequently, air ambulances were established to fly patients from the nursing stations to larger centres, where they would receive the required services.

Provincial nurses attended to the non-treaty population in the North. The few federal nurses present in the North attended to the status Indian population. Numerous jurisdictional issues arose between provincial health care and federal health care. During the latter half of the twentieth century, many provincial nurses were reprimanded for providing care to status Indians. This jurisdictional issue continues to the present day. However, the nurses never refused to provide care; they always found a way to meet the needs of the patient, regardless of treaty status.

In this YouTube video (53:00), titled “Place and Nursing in Remote Northern Communities: A Historical Perspective,” Dr. Lesley McBain discusses historical research conducted with northern Saskatchewan nurses. The research described in this video illustrates some of the challenges faced by outpost nurses while providing care to northern Saskatchewan citizens. In letters to their supervisors, individual nurses bring attention to substandard working environments, which limit their ability to deliver professional care while also having a negative impact upon the welfare of their patients.

After watching the video, answer the following questions:

- According to this research, has the Canada Health Act had an impact on northern communities?

- What changes would you recommend to improve health care in the North?

- How did the frequent relocation of northern nurses impact their “moral proximity,” as described by Malone’s theory of distal nursing discussed in the video?

- If you were a provincial northern nurse, what would you do to ensure that all people receive good care?

Essential Learning Activity 4.3.3

To understand how the development of nurses’ working professionalism over the past 60 years has been linked to changes in societal attitudes, watch this video of Margaret Scaia presenting “Working Professionalism: Nursing in Calgary and Vancouver 1958 to 1977” (51:00).

Summary

Nurses pioneered the provision of holistic health care to Canadians, starting as early as 1617 with Marie Rollet Hébert, who provided care to the early settlers and the Indigenous people. Over the next four centuries, the societal attitudes displayed toward nurses, and their subsequent working conditions, led to nursing shortages. These shortages resulted in the emergence of auxiliary health personnel within the health care workplace.

As nursing education transitioned to universities, nurse researchers and leaders created a unique body of nursing knowledge designed to be used by nurses within their individual practices. This nursing knowledge requires modern nurses to deliver evidence-informed care. Nurses are expected to analyze “practice problems and identify the research that will help them answer questions about how they should go about delivering care” (Lieb Zalon, 2015, p. 425). As holistic practitioners, nurses appraise research and make rational care-provider decisions based on their knowledge of the patient and the health care environment (Rycroft-Malone, 2008).

Many issues identified in the early history of Canadian health care continue to have a significant impact on Canadian nurses today. Understanding nursing’s past will help today’s nurses move forward as they deal with current issues, such as nursing shortages/supply-and-demand issues; health care funding cutbacks with hospitals replacing nurses with lesser skilled workers; blurring of distinctions between licensed practical nurses and registered nurses; implementation of extended nursing practice that allows nurses to realize their full potential; implementation of primary health care; increasing employment of nurse practitioners; development of nursing informatics; focus on self-regulation; reform of nursing curriculum and education delivery; and finally, the constant need to pay close attention to the appropriate compensation of nurses and provision of quality health care work environments. Lessons acquired throughout Canadian history encourage the vigilance of nurse leaders as they build the future for nursing and health care in Canada.

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Identify historical events related to Canadian health care and the role that early nurse leaders played in those events.

- Identify how health care responsibilities have been divided among federal, provincial, and territorial governments.

- Describe how demographic forces and social forces impact nurse leadership within the Canadian health care system.

Exercises

- What are the responsibilities of the federal government under the Canada Health Act? Discuss the impact of dividing the responsibilities for health care between the provincial, territorial, and federal governments.

- Discuss how social forces have had a significant impact upon the roles of nurses in Canadian health care. Provide at least three examples of social forces.

- What changes would you recommend to the Canada Health Act?

References

Bassendowski, S. (2012). A portrait of Saskatchewan nurses in military times. Saskatoon, SK: Houghton Boston.

Calnan, R., & Lemire Rodger, G. (2002). Primary healthcare: A new approach to healthcare reform. Notes for remarks to the Senate standing committee on social affairs, science and technology. Ottawa: Canadian Nurses Association.

Canadian Nurses Association [CNA]. (2013). One hundred years of service. Ottawa: CNA. Retrieved from https://www.cna-aiic.ca/~/media/cna/page-content/pdf-en/cna_history_book_e.pdf?la=en

Dunlop, M. E. (2006). Health Policy. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/health-policy/

Gregory, d., Raymond-Seniuk, C., Patrick, L., & Stephen, T. (2015). An introduction to Canadian nursing. In d. Gregory, C. Raymond-Seniuk, C. Patrick, & T. Stephen (Eds.), Fundamentals:Perspectives on the art and science of Canadian nursing (pp. 3–22). Philadelphia, PA: Walters Kluwer.

Jaenen, C. J. (2008). Marie-Marguerite d’Youville. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/marie-marguerite-d-youville/

Lieb Zalon, M. (2015). Translating research into practice. In P. S. Yoder-Wise, L. G. Grant, & S. Regan (Eds.), Leading and Managing in Canadian Nursing (pp. 411–429). Toronto: Elsevier.

Matthews, M. (2005). Swift Current Health Region. In Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan: A living legacy (pp. 919–920). Regina, SK: Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina.

Noel, J. (2008). Jeanne Mance. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved from http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/jeanne-mance/

Pepper, E. A. (2015). “Over There” in World War II. The Canadian Nurse, 111(8), 8–9.

Rycroft-Malone, J. (2008). Evidence-informed practice: From individual to context. Journal of Nursing Management, 16, 404–408.

The First World War’s nursing sisters. (2016). Canadian Nurse, 112(8), 17.

The war years. (2005). Canadian Nurse, 101(7), 38–41.

Toman, Cynthia (2007). An officer and a lady: Canadian military nursing and the Second World War. Vancouver: UBC Press.

VON Canada. (2017). More than a Century of Caring: Our Proud Legacy. Retrieved from www.von.ca/en/history

World Health Organization [WHO]. (2015). Health in 2015: From MDGs, Millennium Development Goals to SDGs, Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva: WHO. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/200009/1/9789241565110_eng.pdf?ua=1

Feedback/Errata