For centuries, people accepted adversarial disputes and harsh conflict as a by-product of human nature. This acceptance caused people to analyze only how conflict could be resolved, that is, how they could make it go away. In the past decade or two, many people have started to also ask, “Why is conflict resolved in that way?” and, “Might there be a better way?”

If we are to make progress toward better conflict resolution, it is imperative that we understand why conflicts arise and how people traditionally have reacted to conflict situations. When we are able to analyze more clearly the causes of disputes, we will be able to determine better what processes need to be implemented to produce a more positive outcome to the conflict.

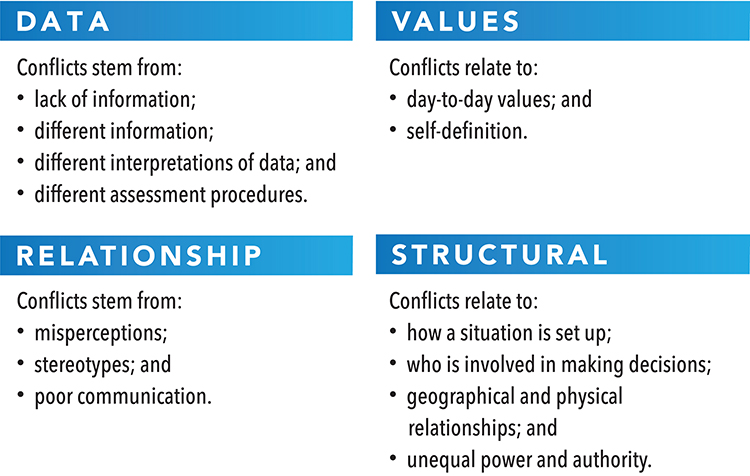

In order to analyze how to transform destructive conflict into a dispute with a positive outcome, let us begin by exploring the four major types of conflict (categorized by cause): data conflicts, relationship conflicts, value conflicts, and structural conflicts.

Data conflicts occur when people lack the information necessary to make wise decisions, are misinformed, disagree over which data are relevant, interpret information differently, or have competing assessment procedures. This type of conflict is usually the simplest to overcome, by adopting a process to ensure both parties perceive the data in the same way.

These problems often result in what have been called unrealistic or unnecessary conflicts since they may occur even when objective pre-conditions for conflict, such as limited resources or mutually exclusive goals, are not present. They occur due to the presence of strong emotion (e.g., jealousy, mistrust, hatred) and are created from perceptions, poor communication, stereotypes, and so on. Relationship conflicts often fuel disputes, causing them to escalate.

This type of conflict is caused by perceived or actual incompatible value systems. Values are beliefs people use to give meaning to life and to explain what is good, bad, right, or wrong. Value conflicts occur only when people attempt to force one’s set of values on another or lay claim to exclusive value systems, which do not allow for divergent beliefs.

Structural conflicts are caused by oppressive patterns of human relationships. These patterns are often shaped by forces external to the people in dispute. Often, the disputants have no reason to be in conflict other than the structural problem that is imposed on their relationship. Often, these conflicts can be overcome by identifying the structural problem and working to change it. Acceptance of the status quo can perpetuate structural conflict.

It is important to understand what type of conflict (data, value, relationship, or structural) you are dealing with before you can effectively work toward a resolution. The solution for each type of conflict will be different and must suit the type of conflict you are addressing. For example, it would be unlikely that you would resolve a relationship problem with a data solution.

Data and structural conflicts have external sources of conflict and are typically easier to resolve; this is done by changing something in the external environment. Conversely, relationship and value conflicts relate to internal sources of conflict and can be much more difficult to resolve. Understanding relationship and value conflicts requires a deep internal awareness and empathy for others. Resolving relationship and value conflicts may significantly challenge an individual’s personal perspectives, which generally makes the process more difficult. Typically, when we are under stress or in an escalated conflict we reach for data or structural solutions to resolve the conflict as these solutions require less time and effort.

Every individual or group manages conflict differently. In the 1970s, consultants Kenneth W. Thomas and Ralph H. Kilmann developed a tool for analyzing the approaches to conflict resolution. This tool is called the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) (Kilmann Diagnostics, 2017).

Thomas and Kilmann suggest that in a conflict situation, a person’s behaviour can be assessed on two factors:

Thomas and Kilmann use these factors to explain the five different approaches to dealing with conflict:

There is an appropriate time to use each approach in dealing with conflict. While most people will use different methods in various circumstances, we all tend to have a more dominant approach that feels most comfortable. One approach is not necessarily better than another and all approaches can be learned and utilized. To most effectively deal with conflict, it is important to analyze the situation and determine which approach is most appropriate.

Let’s take a closer look at each approach and when to use it.

An avoidance approach demonstrates a low commitment to both goals and relationships. This is the most common method of dealing with conflict, especially by people who view conflict negatively.

A competing approach to conflict demonstrates a high commitment to goals and a low commitment to relationships. Individuals who use the competing approach pursue their own goals at the other party’s expense. People taking this approach will use whatever power is necessary to win. It may display as defending a position, interest, or value that you believe to be correct. Competing approaches are often supported by structures (courts, legislatures, sales quotas, etc.) and can be initiated by the actions of one party. Competition may be appropriate or inappropriate (as defined by the expectations of the relationship).

Accommodating

Table 11.3.3 Accommodating

|

Types of

Accommodating

|

Results

|

Appropriate When

|

- Playing down the conflict to maintain surface harmony

- Self-sacrifice

- Yielding to the other point of view

|

- Builds relationships that will allow you to be more effective in future problem solving

- Increases the chances that the other party may be more accommodating to your needs in the future

- Does not improve communication

|

- You are flexible on the outcome, or when the issue is more important to the other party.

- Preserving harmony is more important than the outcome.

- It’s necessary to build up good faith for future problem solving.

- You are wrong or in a situation where competition could damage your position.

|

Application to Nursing—Accommodation

When might accommodation be an appropriate approach to conflict in a hospital or clinic setting?

It may be appropriate to use an accommodating approach when, for example, one of the nurses on your shift has a particularly difficult patient who is taking up a lot of time and effort. Seeing that the nurse is having difficulty, you take on some of her or his tasks. This increases your workload for a period of time, but it allows your colleague the time needed to deal with the difficult patient.

When might accommodation be an inappropriate approach to conflict in a hospital or clinic setting?

This approach may no longer be appropriate if that same nurse expects you to continue to cover his or her tasks after the situation with the difficult patient has been resolved.

Compromising

Table 11.3.4 Compromising

|

Types of

Compromising

|

Results

|

Appropriate When

|

- Splitting the difference

- Exchanging concessions

- Finding middle ground

|

- Both parties may feel they lost the battle and feel the need to get even next time.

- No relationship is established although it should also not cause relationship to deteriorate.

- Danger of stalemate

- Does not explore the issue in any depth

|

- Time pressures require quick solutions.

- Collaboration or competition fails.

- Short-term solutions are needed until more information can be obtained.

|

Application to Nursing—Compromise

When might compromise be an appropriate approach to conflict in a hospital or clinic setting?

You are currently on shift with another nurse that does the bare minimum and rarely likes to help his or her colleagues out. It is two hours since lunch and one of your hyperglycemic patients have not received their lunch tray. You approach your colleague and ask him or her to go look for the tray while you draw blood from a patient for them. The other nurse agrees as he or she has been having difficulty with the patient that needs a blood draw.

When might a compromise be an inappropriate approach to conflict in a hospital or clinic setting?

It would be inappropriate to continue to ask the nurse to do tasks for you that are less appealing than the tasks you take on.

Collaborating

Collaborating is an approach that demonstrates a high commitment to goals and also a high commitment to relationships. This approach is used in an attempt to meet concerns of all parties. Trust and willingness for risk is required for this approach to be effective.

Table 11.3.5 Collaborating

|

Type of

Collaborating

|

Results

|

Appropriate When

|

- Maximizing use of fixed resources

- Working to increase resources

- Listening and communicating to promote understanding of interests and values

- Learning from each other’s insight

|

- Builds relationships and improves potential for future problem solving

- Promotes creative solutions

|

- Parties are committed to the process and adequate time is available.

- The issue is too important to compromise.

- New insights can be beneficial in achieving creative solutions.

- There is a desire to work through hard feelings that have been a deterrent to problem solving.

- There are diverse interests and issues at play.

- Participants can be future focused.

|

Application to Nursing—Collaboration

When might collaboration be an appropriate approach to conflict in a hospital or clinic setting?

It may be appropriate to use collaboration in a hospital or clinic setting when discussing vacation cover off with team members at a team meeting. During a team meeting, time is available to discuss and focus on what is important for each member of the team.

When might collaboration be an inappropriate approach to conflict in a hospital or clinic setting?

Collaboration would be inappropriate in a discussion of a new policy that has been put in place if the team has little influence in making adjustments.

11.4 What Does Each Approach Need?

There are times when others may take an approach that is not helpful to the situation. However, the only person that you can control in a conflict is yourself. It is important to be flexible and shift your approach according to the situation and the other people with whom you are working. When someone else is taking an approach that is not beneficial to the situation, it is critical to understand what needs underlie the decision to take that approach. Here are a few examples:

Avoiders may need to feel physically and emotionally safe. When dealing with avoiders, try taking the time to assure them that they are going to be heard and listened to.

Competitors may need to feel that something will be accomplished in order to meet their goals. When dealing with competitors, say for example, “We will work out a solution; it may take some time for us to get there.”

Compromisers may need to know that they will get something later. When dealing with compromisers, say for example, “We will go to this movie tonight, and next week you can pick.” (Be true to your word.)

Accommodators may need to know that no matter what happens during the conversation, your relationship will remain intact. When dealing with accommodators, say for example, “This will not affect our relationship or how we work together.”

Collaborators may need to know what you want before they are comfortable sharing their needs. When dealing with collaborators, say for example, “I need this, this, and this. . . . What do you need?”

Essential Learning Activity 11.4.1

Take an online test by Bacal and Associates from their webpage Conflict Quizzes and Assessments to find out your preferred approach to conflict.

All approaches to conflict can be appropriate at some times, and there are times when they can be overused. It is important to take the time to consider which approach would be most beneficial to the situation in question. Taking the wrong approach can escalate conflict, damage relationships, and reduce your ability to effectively meet goals. The right approach will build trust in relationships, accomplish goals, and de-escalate conflict.

Everyone has the capacity to use each approach to conflict and to shift from his or her natural style as needed. We react with our most dominant style when we are under stress, but other styles can be learned and applied with practice and self-awareness. When dealing with others who may not have developed their capacity to shift from their preferred style of conflict, it is important to listen for their underlying needs. By understanding the needs that exist beneath the surface of the conflict, you can work with the other person toward a common goal.

11.5 How Conflict Escalates

Note: The information in this section has been adapted from Speed Leas’

Levels of Conflict, published by the Center for Congregational Health.

Many academics and conflict resolution practitioners have observed predictable patterns in the way conflict escalates. Conflict is often discussed as though it is a separate entity, and in fact it is true that an escalating dispute may seem to take on a life of its own. Conflict will often escalate beyond reason unless a conscious effort is made to end it.

The following is an example of an escalating conflict. Most people will recognize their own actions in the description.

A conflict begins . . .

- The parties become aware of the conflict but attempt to deal with it sensibly. Often, they will attribute the problem to “a misunderstanding” and indicate that “they can work it out.”

- The parties begin to slide from cooperation to competition. (“I’ll bend but only if they will first.”) They begin to view the conflict as resulting from deliberate action on the part of the other. (“They must have known this would happen.”) Positions begin to harden and defensiveness sets in, which creates adversarial encounters. Parties begin to take actions to strengthen their positions and look to others for support. (“Don’t you feel this is reasonable?” “Do you know what that idiot is doing to me?”)

- As communication deteriorates, parties rely more on assumptions about the other and attribute negative motives to them. (“I’ll bet they are going to . . . ,” “Those sorts of people would . . . ,” “Their thinking is so muddled, they must . . .”) Groupthink often takes over as each disputant seeks support from others. (“We have to appear strong and take a united front.”) Parties begin to look for more evidence of other problems—their beliefs feed their observations.

- Parties soon believe that cooperation cannot resolve the problem because of the actions of the other, and aggressive actions are planned. (“I’ve tried everything to get them to see reason.” “It’s time to get tough with them.” “I’m going to put a stop to this.”)

- Parties begin to feel righteous and blame the other for the whole problem. Generalizing and stereotyping begin. (“I know what those people are like. . . . We can’t let them get away with this.”) Parties begin to be judgemental and moralistic, and believe they are defending what is right. (“It’s the principle of the matter.” “What will people say if we give in to this?”)

- The conflict becomes more complicated but also more generalized and personalized. Severe confrontation is anticipated and, in fact, planned for, thus making it inevitable. The parties view this as acceptable as the other has, in their mind, clearly shown they are lacking in human qualities. (“He’s just a jerk; we’ll have to really hit him hard.”)

- All parties appears now to believe that the objective of the conflict is to hurt others more than they are being hurt. (“I’ll make you pay even if we both go down over this.”) The dispute is beyond rational analysis; causing damage to the other, even at your own expense, is the main focus. (“Whatever it takes . . .” “There is no turning back now.” “They won’t make a fool out of me.”)

- Finally, destruction of the other, even if it means self-destruction as well, is the driving force. (“If it takes everything I have, for the rest of my life . . .”)

Figure 11.5.1 is called the conflict escalation tornado. It demonstrates how conflict can quickly escalate out of control. By observing and listening to individuals in dispute, it is often possible to determine where they are in the escalation process and anticipate what might occur next. In doing so, one can develop timely and appropriate approaches to halt the process.

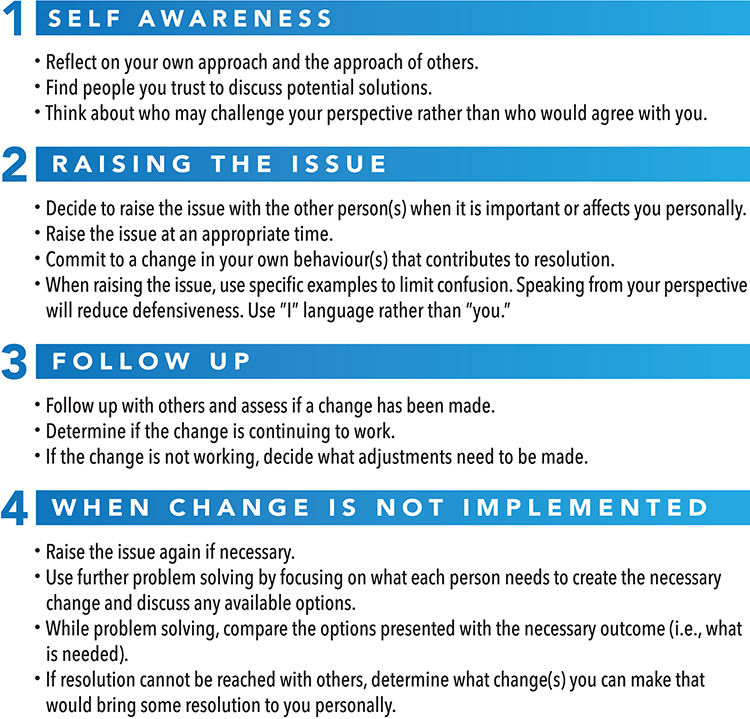

11.6 How to Get Off the Spiral: Stopping Escalation

An appropriate level of risk must be taken by the individuals involved to de-escalate the conflict. Taking these risks can be scary as it requires people to be vulnerable and express emotions. A nurse leader’s emotional intelligence plays an important role in the de-escalation of conflict. By taking risks to de-escalate conflict, whether the result is successful or unsuccessful, the nurse leader sends a message of wanting to rebuild trust, respect, and effective communication. Risk taking can also provide an opportunity to make necessary change by learning and developing new behaviours and capacities to work effectively as individuals and as work units.

Typically, when conflict is not de-escalated and resolved appropriately, it results in more conflict in the relationship. The relationship continues in a state of heightened sensitivity to actions, and assumptions can be formed quickly. Actions that may previously have been viewed as innocent or acceptable may be perceived as threatening. Every unresolved conflict reduces the time it takes to get to the top of the tornado because of this heightened sensitivity. The following steps are suggestions for use at every stage of conflict escalation. The ability to harness fear and be vulnerable is a critical step for de-escalation.

Research Note

Amestoy, S. C., Bakes, V. M. S., Thofehrn, M. B., Martini, J. G., Meirelles, B. H. S., & Trindade, L. L. (2014). Conflict in nursing management in the hospital. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 35(2). 79–85. doi:10.1590/1983-1447.2014.02.40155

Article review

The study outlined in this article takes a qualitative, descriptive approach, which includes case studies used as an investigational strategy to determine the main conflicts experienced by nurse leaders in the hospital environment, as well as the strategies adopted for dealing with such. The study included 25 nurses in three hospitals in Florianopolis, Santa Catarina, Brazil. Semi-structured interviews, non-participant observations, and dialogical workshops were used to collect data. A thematic analysis was undertaken to analyze the data gathered. What the study found was the most prevalent conflict that emerged in the health sector stemmed from the interpersonal relationships of those working in the health field. The study also put an emphasis on the power dynamics that could relate to the interpersonal conflicts in the health sector.

The study found that management of these interpersonal conflicts is necessary, as are strategies to deal with them. Management of these interpersonal conflicts is critical to the health sector because of the paralysis or overwork that can accompany conflict in nursing teams, and between nurses and other health professionals, such as physicians. The best strategy outlined in this study for dealing with interpersonal conflict is a democratic, involved style where team members are included in decision making. The impact this will have on the field of nursing is encouraging. The authors recognize a limitation of this study: the fact that the availability and shift patterns of nurses make it difficult to perform the involved kind of research undertaken in this study. What is hoped is that this information will encourage the integration of interpersonal conflict management training into the work and training materials provided to nurses through their education.

Summary

Conflict is inevitable, especially for leaders. Effective nurse leaders invest time understanding the causes of conflict and learn how to manage and resolve it. The first step to managing conflict is to reflect on your own experiences and understand your personal approach to conflict. After learning their own preferred style, good leaders learn to understand the styles of others and adapt their approaches accordingly. They observe and practice de-escalating situations and coaching people toward resolution. Fortunately, managing conflict is not something to be feared; rather, it is something that can be learned and practised. It just takes time.

Change the way you think about disagreements, and how you behave during conflict. Be willing to listen, engage directly, constructively, and collaboratively with your colleagues.

—Cloke and Goldsmith, 2011

After completing this chapter, you should now be able to:

- Describe the different causes of conflict.

- Verbalize the different approaches to managing conflict.

- Recognize how conflict escalates.

- Adapt your approach to conflict.

Exercises

1. Read this scenario and answer the questions that follow.

Jill and Neil are both nurses working the same shift. Jill is responsible for patients in rooms 1–6 and Neil is responsible for patients in rooms 7–12. Over the course of their shift, both nurses routinely visit their patients’ rooms to take vitals and deliver medication.

On one of his rounds, Neil attends to his patient in room 8. He reads the chart and notices Jill’s initials signaling that she had already checked on this patient. A bit confused, he continues on to his next patient. After another hour goes by, Neil returns to room 8 and again notices Jill’s initials on the chart. Neil thinks to himself, “What is she doing? I’ve got it covered. She’s checking my work. She must think I’m incompetent.” Neil decides to approach Jill and see what is going on.

Questions:

a) What might have been the initial cause of the conflict?

b) What kind of conflict did it turn into?

c) If Neil provides Jill with a copy of the room assignments, would that resolve the conflict?

2. Read this scenario and answer the questions that follow.

A nursing team is having a routine meeting. One of the nurses, Stephen, is at the end of a 12-hour shift and another nurse, Tanya, is just beginning hers. Tanya is a senior nurse in the unit with over ten years’ experience on this specific unit. Stephen is new to the unit with less than three years’ experience in nursing. Tanya has been asked to present information to the team about effective time management on the unit. During Tanya’s presentation, Stephen is seen rolling his eyes and talking to other members of the team. Tanya breaks from her presentation and asks “Stephen, do you have anything to add?” Stephen replies, “No, I just don’t know why we need to talk about this again.” Tanya chooses to avoid engaging with Stephen further, and finishes her presentation. Stephen continues to be disruptive throughout the presentation.

After the meeting concludes, Tanya approaches Stephen and asks if he had anything to add from the meeting. Stephen replies, “No, I don’t have anything. I just think we all know what the procedure is because we just learned it all during orientation training. Maybe if you don’t remember the training, you should take it again.” Tanya is shocked by his reply and quickly composes herself. She states, “Stephen, I have worked on this unit for over ten years. I was asked to present that information because there are current issues going on among the staff. Next time please respect my authority and listen to those who come before you.”

Questions:

a) What types of conflict are present?

b) What will need to happen to resolve this issue between Tanya and Stephen?

3. Take a moment to think about what your preferred approach to conflict may be. How might you adapt your approach to conflict when working with others?

4. Read this scenario and answer the questions that follow.

Connie, the head nurse on Unit 7, is a respected member of the team. She has been working on this unit for a number of years and is seen by the other nurses as the “go to” person for questions and guidance. Connie is always thorough with patients and demonstrates excellence and quality in her work. Dr. Smith is a well-respected member of the medical profession and an expert in his field of medicine. He has a reputation for excellent bedside manner and is thorough in his approach with patients.

Connie is four hours into her 12-hour shift when she is approached by Dr. Smith. He asks, “Connie, why has the patient in room 2 not received his blood pressure medication over the past few days? I was not notified about this!”

Connie, trying to find a quick solution, replies, “I didn’t know that patient had been missing medication. I’ll go check on it and get back to you.”

Dr. Smith is persistent, saying, “You don’t need to go check anything. I know this patient and should have been informed about the withholding of medication and the reasons why.”

Connie, again attempting to find a resolution, states, “Well, there must be some communication about this change somewhere . . .”

“There isn’t!” Dr. Smith interrupts.

Connie becomes upset and decides to leave the conversation after declaring, “Fine, if you know everything then you figure it out, you’re the one with the medical degree, aren’t you?” She storms off.

Connie makes her way to the nurses’ station where Dan and Elise are assessing charts and says to them, “You will not believe what Dr. Smith just said to me!”

Dan and Elise look shocked and ask “What?”

Connie explains, “Well, he thinks I don’t do my job, when really we nurses are the ones that keep this unit going. Who is he to question my ability to look after patients? I am the most knowledgeable person on this unit!”

Dan and Elise don’t know how to reply and decide to avoid the interaction with a simple “Oh yeah.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Smith has made his way to the doctor’s lounge and finds his colleague Dr. Lee. Dr. Smith tells him, “That head nurse on Unit 7 is useless. She doesn’t know what she is doing and doesn’t understand that we must be informed about changes to our patients’ medications, does she?” Dr. Lee nods quickly and returns to reviewing his file.

About three hours later, Connie and Dr. Smith have each spoken to several people about the interaction. Connie bumps into another nurse, Jessie, one of her best friends. Connie pulls Jessie aside and says, “You will not believe what I just saw. I was going into the admin office to file my holiday requests and out of the corner of my eye, I see Dr. Smith lurking around the corner, pretending to look at a chart, spying on me!”

“What? Are you serious? That’s not safe,” replies Jessie.

Connie is relieved that Jessie is taking her side—it makes her feel like she is not going crazy. “Yeah, I’m really getting worried about this. First that creep is accusing me of not doing my job, then he is wasting his time spying on me. What a loser! Maybe what I should do is file a complaint. That’ll show the “big man” that he isn’t that big around here and maybe take him down a notch.”

When Jessie gives her an apprehensive look, Connie continues, “Oh Jessie, don’t worry. I have a perfect record and this won’t affect me. Even if it does, I will have done something good for all the other nurses around here. It is the principle of the matter at this point.”

Meanwhile, Dr. Smith has run into an old classmate of his, Dr. Drucker, and says, “Wow! You got hired! So happy to have you in the hospital. I do need to tell you though to be careful of the head nurse on Unit 7 . . .” Dr. Smith describes his troubles with Connie and adds, “She’s a real snitch! She makes trouble out of nothing. I was reviewing a chart down the corridor from the admin office, minding my own business and actually getting my work done, when I saw her slip into the admin office to squeal about me to the top bosses! This is something that needs to be watched! We can’t have people reporting doctors to administration over nothing. I think I’m going to write her up and get a black mark on that perfect record of hers. I will be fine—everyone knows I’m right. There will be consequences for her.”

Questions:

a) Using the scenario above, identify the stages of the conflict escalation tornado.

b) What suggestions might you give to Dan, Elise, Jessie, Dr. Lee, and Dr. Drucker about how to respond to Connie and Dr. Smith?

c) How do you think this conflict will be resolved?

References

Amestoy, S. C., Bakes, V. M. S., Thofehrn, M. B., Martini, J. G., Meirelles, B. H. S., & Trindade, L. L. (2014). Conflict management: Challenges experienced by nurse-leaders in the hospital environment. Revista Gaúcha de Enfermagem, 35(2). 79–85. doi:10.1590/1983-1447.2014.02.40155

Cloke, K., & Goldsmith, J. (2011). Resolving conflicts at work: Ten strategies for everyone on the job (3rd ed.). San Francisco: John Wiley & Sons.

Leas, S. (2011). Levels of conflict. Center for Congregational Health. Retrieved from https://cntr4conghealth.wordpress.com/2011/09/01/levels-of-conflict-by-speed-leas/

Oxford Dictionaries online. (n.d.). https://www.oxforddictionaries.com/

Reagan, Ronald. (1982). Address at commencement exercises at Eureka College (Eureka, Illinois). Reagan Library. Retrieved from https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/archives/speeches/1982/50982a.htm

Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario. (2012). Healthy work environment best practice guidelines: Managing and mitigating conflict in health-care teams. Retrieved from http://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/Managing-conflict-healthcare-teams_hwe_bpg.pdf

Thomas, K. W., & Kilmann, R. H. (2017). An overview of the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI). Kilmann Diagnostics. Retrieved from http://www.kilmanndiagnostics.com/overview-thomas-kilmann-conflict-mode-instrument-tki

Feedback/Errata