30

We start with lecture-based teaching methods that have been moved into a technological format with little change to the overall design principles. I will argue that these are essentially old wine in new bottles.

4.2.1 Live, streamed video

This is basically a classroom lecture delivered at the time of delivery to remote students (although there may also be live students in the lecture theatre as well – this is sometimes called bi-modal teaching. For an example of this, see here.). The remote students may be watching on their own at home, work or in transit, or in small groups at another campus or local learning centre. There is no change in the design from an in-person lecture, although the instructor may need to make sure that the remote students are not ignored if there are questions or discussion. Because the lecture is live, and everyone attends at the same time (even though they may be in different places), the teaching is synchronous. For an example, see here.

Live streamed video is often the first step instructors take into online learning, because they do not have to do anything new other than learn how to set up and switch on the equipment. As the technology became cheaper and easier to use, the use of live streamed lectures doubled between 2016 and 2017 in Canada (Bates et al., 2018). When the Covid-19 pandemic suddenly burst onto the scene in March, 2020, and instructors and teachers had to pivot immediately to emergency remote learning, this was the method adopted by the majority, mainly using Zoom or other online video-conferencing technologies. The advantage of Zoom or similar video-conferencing software is that it can be used from anywhere with an internet connection by instructors and students.

Some instructors require all students to be present during the live lecture in order to ensure participation, but this can be counter-productive if the aim of going online is to increase flexibility for students. This flexibility can be accommodated by also recording the lecture.

4.2.2 Recorded and streamed lectures

Lectures can be recorded in two main ways.

- if using Zoom or a similar online video-conferencing system, the session can be recorded and made available for later use by students. Depending on the licensing agreement, there is often a limit on how long the video will remain available, but it can be kept usually for at least a couple of months or to the end of a semester.

- lecture capture technology such as Panopto or Kaltura is another, older, technology that allows a ‘live’ classroom lecture to be recorded and stored on a server for later streaming to students. The lecture capture equipment is usually installed in the lecture theatre. This technology, which automatically records a classroom lecture once activated by the lecturer, was originally designed to enhance the classroom model by making lectures available for repeat viewings online at any time for students regularly attending classes – in other words, a form of homework or revision.

Lecture capture led to the development of massive open online courses (xMOOCs), such as those offered by Coursera, Udacity and edX. These MOOCs were originally classroom lectures recorded using lecture capture technology at Stanford, MIT and Harvard, and then made available to the general public over the internet.

The main advantage of recording lectures is to allow all students (those present and those that missed the lecture) to review the lecture at their leisure. Thus recording lectures is an asynchronous technology, in that the lectures can be viewed at any time and any place with Internet access. Lecture capture is a more permanent alternative to using the recording facility in video-conferencing software such as Zoom, although video-conferencing software can be used from anywhere with an Internet connection.

Recorded video can be integrated with a learning management system (see 4.2.3 below). Passwords can be used to limit access to the recorded videos to registered students only. In some cases, making recordings of lectures available to students has been shown to reduce student drop-out dramatically.

Flipped classrooms, which pre-record a lecture for students to watch on their own, followed by discussion in class, are an attempt to exploit more fully this potential (for an example see here).

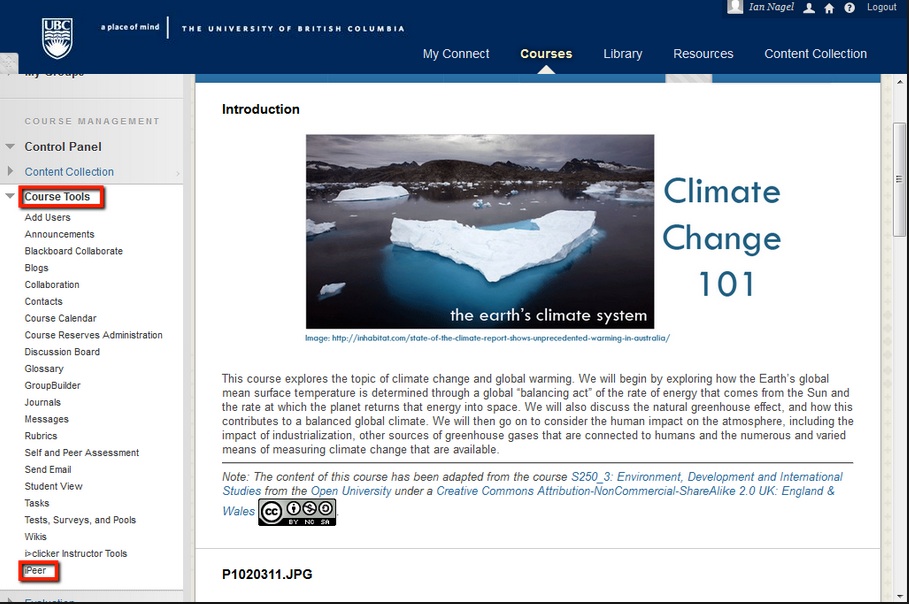

4.2.3 Lecture-based courses using learning management systems

Learning management systems (LMSs), such as Blackboard, Canvas, D2L and Moodle, are software that enable instructors and students to log in and work within a password protected online learning environment. LMSs can be used in a variety of ways. In this section the focus is on using an LMS to mirror a lecture-based approach to teaching. The main difference is that the student using an LMS is working asynchronously.

The software allows the instructor or teacher to organise the student work into weekly units or modules. The lecture can either be written, often in the form of Powerpoint slides, or delivered as a video. The instructor selects and presents the material to all students, a large class enrolment can be organized into smaller sections with their own instructors or adjunct faculty, there are opportunities for (online) discussion, students work through the materials at roughly the same pace, and assessment is by end-of-course tests or essays. The learning management system is primarily an asynchronous technology, in that students can access the software at any time and any place with an internet connection.

Originally LMSs were primarily text-based, but now they can integrate both live or recorded video, such as Zoom meetings or streamed lectures.

The main design differences with video-based or classroom lectures is that in an LMS:

- the content is primarily text based rather than oral (although increasingly video and audio are now integrated into LMSs),

- the student-teacher interaction and online discussion are mainly asynchronous rather than synchronous,

- students are assigned online work within the LMS to follow up on the instructor-provided material

- the course content is available at any time from anywhere with an Internet connection.

These are important differences from a physical classroom, and skilled teachers and instructors can modify or adapt LMSs to meet different teaching or learning requirements (as they can in physical classrooms), but the basic organizing framework of the LMS (weekly modules, regular assessment, and interaction between students and with an instructor) remains the same as for a physical classroom.

Nevertheless, the LMS is still an advance over online designs that merely put lectures on the Internet as pre-recorded videos, or load up pdf copies of Powerpoint lecture notes, as is still the case unfortunately in many online courses.

Perhaps of most importance though is that most LMSs embed good design principles, such as:

- requiring clearly stated learning objectives,

- a clear weekly work structure for students,

- opportunities for online discussion,

- opportunities for feedback from instructors, and

- continuous and/or summative assessment.

These features are built in to the software to guide instructors in their design. Other ways of designing teaching with an LMS will be discussed later in this chapter.

4.2.3 Strengths of the lecture-based model for online learning

Old wine can still be good wine, whether the bottle is new or not. If lecturing was considered good practice and effective in-person, then one might reasonably expect it to be equally effective online.

Secondly, in an emergency such as the pandemic, and with relatively easy to use tools such as online video-c0nferencing systems and lecture capture, instructors and teachers can make a rapid pivot to maintain student education even though neither students nor instructors can access a school or campus. In an emergency there is not time to re-design curricula or teaching methods, or to train teachers and faculty in alternative methods of teaching.

Third, recording and streaming lectures on demand not only allows more flexibility for students who have difficulty in getting to school or campus, but also allows students to replay, review and analyse the lecture more closely. In short it allows students to spend more time on task.

Fourth, once recorded the lecture can be used again with a different class in a different year. This can subsequently free up some of the instructors’ time for more interaction with students.

4.2.4 Weaknesses of the lecture-based model for online learning

First, all of the limitations of in-person, lecture-based teaching outlined in Chapter 3.3 are carried over and if anything magnified when lectures are moved online.

The most important limitation though of lecture-based online learning is that students studying online are in a different learning environment or context than students learning in a classroom, and the design needs to take account of this. In particular, students are working in isolation. As a result, for motivational reasons, they need more interaction online with the instructor and other students than in an in-person lecture. It is also unhealthy for students to be watching a screen for six hours a day (see Cross, 2022), if all classes are organised around transmissive lectures. This limitation of lecture-based teaching becomes more serious the younger the student, or the less self-disciplined the student. Students who struggle in an in-person teaching context tend to struggle even more in an online context where the lecture model is used (see, for instance, Figlio et al., 2013).

The need to re-design teaching for an online environment will be discussed more fully in the rest of the book, but if online lectures are used they need to be modified, and in particular the time spent on video lectures needs to be reduced, to allow time for students to work asynchronously and for the instructor to have more time for interaction with students.

Thirdly the lecture-based online learning design fails to meet the changing needs of a digital age. It is important then to look at teaching methods that make the most of the educational affordances of new technologies, because unless the design changes significantly to take full advantage of the potential of the technology, the outcome is likely to be no better and more likely much worse than that of the physical classroom model which it is attempting to imitate. This is discussed more fully in Chapter 7 and Chapter 8.

Lastly, the danger of just adding new technology to the classroom design is that we may just be increasing cost, both in terms of technology and the time of instructors, without changing outcomes.

4.2.5 Summary

Moving transmissive lectures online in March 2020 was a justifiable necessity. There was not time to do anything else. Doing the same thing in January 2022, nearly two years later, is not acceptable. There has been plenty of time to re-design online teaching to make better use of its strengths, particularly asynchronous learning that students can do online individually or in online groups.

In the school (k-12) system in particular, this requires a complete change of teaching methods for online learning. At the time of writing (January 2022) this has not occurred in most school systems, mainly because of failure to train teachers in online learning or to use specialists in online learning to help change curricula. Also younger children in particular need to be in school for a wide range of reasons. Online learning therefore needs to be used very selectively in the school system.

In the post-secondary system, the challenge has not been so great. Many universities and colleges already had experience of online learning before Covid-19, and had the specialist instructional designers and resources needed to train faculty in online learning. The main difficulty has been instructors’ reluctance to move away from the tried and trusted lecture method, for reasons given in Chapter 3.3, and the difficulty of scaling up support for blended or online learning.

There is also enough flexibility in the design of learning management systems for them to be used in ways that break away from the traditional lecture-based model, which is important, as good online design should take account of the special requirements of online learners, so the design needs to be different from that of an in-person classroom model. We will look at other of ways to do this in the rest of this chapter.

Education is no exception to the phenomenon of new technologies being used at first merely to reproduce earlier design models before they find their unique potential. However, changes to the basic design model are needed if the demands of a digital age and the full potential of new technology are to be exploited in education.

References

Bates, A. et al. (2018) Tracking Online and Distance Education in Canadian Universities and Colleges: 2017 Halifax NS: Canadian Digital Learning Research Association

Cross, J. (2022) What does too much screen time do to children’s brains? Health Matters, New York-Presbyterian

Figlio, D., M. Rush and Yin, L. (2013) Is It Live or Is It Internet? Experimental Estimates of the Effects of Online Instruction on Student Learning Journal of Labor Economics, Volume 31, Number 4

Activity 4.2 Moving the lecture-based model online

1. What are the advantages and disadvantages of breaking up a 50 minute lecture into say five 10 minute chunks for recording? Would you call this a significant design change – if so, what makes it significant?

2. What are the advantages and disadvantages of reducing online lecture time and increasing the time that students spend asynchronously online?

3. Can you think of a simple alternative to using video lectures for putting your courses online?

For my response to these three questions listen to the podcast below (new for Third Edition):