92

12.3.1 Open textbooks

Textbooks are an increasing cost to students. Some textbooks cost $200 or more, and in the USA a university undergraduate spends on average between $530 – $640 a year on textbooks (Hill, 2015), although the cost of recommended textbooks is between $968 and $1221 (Caulfield, 2015).

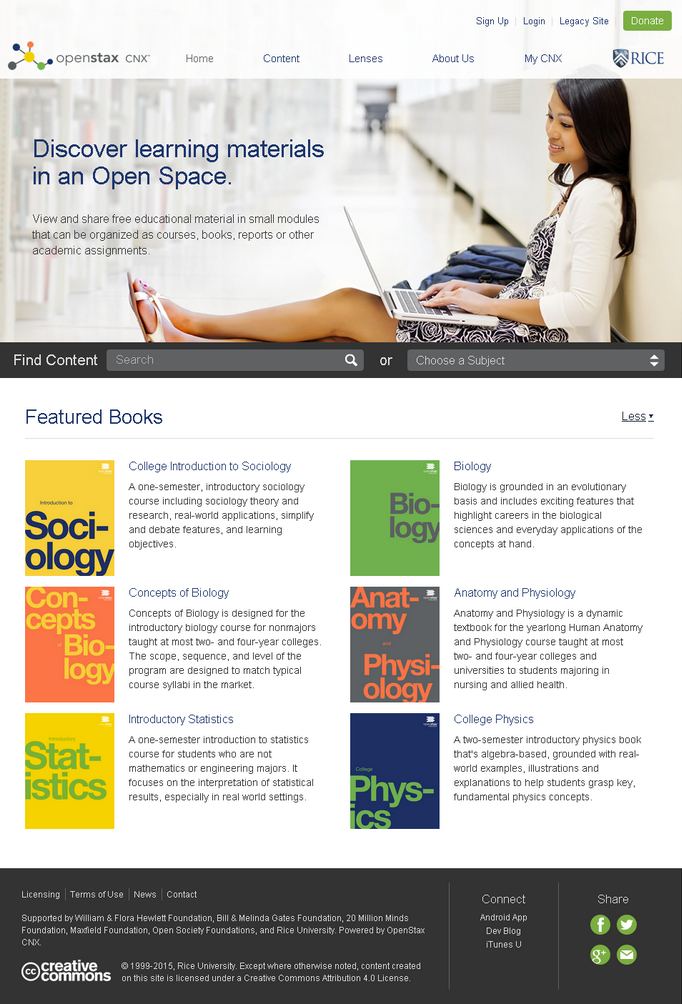

An open textbook on the other hand is an openly-licensed, online publication free for downloading for educational or non-commercial use. You are currently reading an open textbook. There is an increasing number of sources for open textbooks, such as OpenStax College from Rice University, and the Open Academics Textbook Catalog at the University of Minnesota.

In British Columbia, the provincial government funded the B.C. open textbook project, which operated in collaboration initially with the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, but now also with other provinces through the Canada OER Group. The B.C. open textbook project focuses on making available openly-licensed textbooks in the highest-enrolled academic subject areas and also in trades and skills training. In the B.C. project, as in many of the other sources, all the books are selected, peer reviewed and in some cases developed by local faculty. Often these textbooks are not ‘original’ work, in the sense of new knowledge, but carefully written and well illustrated summaries of current thinking in the different subject areas.

12.3.1.1 Advantages of open textbooks

Students and governments, through grants and financial aid, pay billions of dollars each year on textbooks. Open textbooks can make a significant impact on reducing the cost of education. Approximately 86,000 students in B.C. have saved as much as $9 million since the open textbook project first launched in 2012 and that number continues to grow through advocacy and collaboration with the B.C. post-secondary system (Beattie, 2018).

Cable Green, the Interim CEO of the Creative Commons, has a ‘vision’ for open textbooks: 100 per cent of students have 100 per cent free, digital access to all course materials by day one. That is far from the case today.

Donaldson et al. (2019) at the Florida Virtual Campus found in a survey of students in all Florida state universities that due to high costs of textbooks:

- 64% of students did not purchase the required textbook;

- 43 percent were taking fewer courses;

- 23 percent dropped a course;

- students purchased 3.6 textbooks that were not used during his or her academic career.

There are also other considerations. It is a common sight to see lengthy line-ups at college bookstores all through the first week of the first semester (which eats into valuable study time). Because students may be searching for second-hand versions of the books from other students, it may well be into the second or third week of the semester before students actually get their copy.

So why shouldn’t government pay the creators of textbooks directly, cut out the middleman (commercial publishers), save over 80 per cent on the cost, and distribute the books to students (or anyone else) for free over the Internet, under a Creative Commons license?

12.3.1.2 Limitations of open textbooks

Faculty resistance is still a problem for open textbooks. Open textbooks had been adopted in between half and two thirds of all post-secondary institutions in Canada in 2017, and a further 20 per cent were exploring their use. However, this varied considerably by province. In British Columbia, 90 per cent of all post-secondary institutions had adopted open textbooks for some courses; in Saskatchewan and Quebec, less than a third of institutions were using open textbooks (Donovan et al., 2018). This indicates clearly the impact of government support for open textbooks. Adoption was highest in universities and large institutions. Donovan et al. also found that there was a lack of knowledge and even more so of training for instructors in the use of open textbooks and OER.

Murphy (2013) has questioned the whole idea of textbooks, whether open or not. She sees textbooks as a relic of 19th century industrialism, a form of mass broadcasting. In the 21st century, students should be finding, accessing and collecting digital materials over the Internet. Textbooks are merely packaged learning, with the authors doing the work for students. Nevertheless, it has to be recognized that textbooks are still the basic currency for most forms of education, and while this remains the case, open textbooks are a much better alternative for students than expensive printed textbooks.

Quality also remains a concern. There is an in-built prejudice that ‘free’ must mean poor quality. Thus the same arguments about quality of OER also apply to open textbooks. In particular, the expensive commercially published textbooks usually include in-built activities, supplementary materials such as extra readings, and even assessment questions. Nevertheless, Jhangiani and Jhangiani (2017), in a survey of 320 undergraduate students in British Columbia who had actually used an open textbook for one or more of their courses, found that 96 per cent of respondents perceived the quality of their open textbook to be equal or superior to a commercial textbook.

Others (including myself) question the likely impact of ‘open’ publishing on creating original works that are not likely to get subsidized by government because they are either too specialized, or are not yet part of a standard curriculum for the subject; in other words will open publishing impact negatively on the diversity of publishing? What is the incentive for someone now to publish a unique work, if there is no financial reward for the effort? Writing an original, single authored book remains hard work, however it is published.

Although there is now a range of ‘open’ publishing services, there are still costs for an author to create original work. Who will pay, for instance, for specialized graphics, for editing or for review? I have used my blog to get sections of this book reviewed generally, and this has proved extremely useful. Also, one can still approach top quality reviewers for an independent review, as was done for this book (see Appendix 3). I also received free technical support from both BCcampus and Contact North, but other potential open textbook authors may not have that kind of support.

Marketing is another issue. It takes time and specialised knowledge to market books effectively. On the other hand, my experience, having published twelve books commercially, is that publishers are very poor at properly marketing specialised textbooks, expecting the author to mainly self-market, while the publisher still takes 85-90 per cent of all sales revenues. Nevertheless there are still real costs in marketing an open textbook.

How can all these costs be recovered? Much more work still needs to be done to support the open publishing of original work in book format. If so, what does that mean for how knowledge is created, disseminated and preserved? If open textbook publishing is to be successful, new, sustainable business models will need to be developed. In particular, some form of government subsidy or financial support for open textbooks is probably going to be essential.

Nevertheless, although these are all important concerns, they are not insurmountable problems. Just getting a proportion of the main textbooks available to students for free is a major step forward. To see whether or not I felt it worthwhile to write the first edition of this book, see ‘Writing an Online Book: Is it Worth it?’ (Bates, 2015). Seven years later, I have not changed my mind.

12.3.1.3 Learn how to adopt and use an open textbook

BC campus has mounted a short MOOC on the P2PU portal on Adopting Open Textbooks. Although the MOOC may not be active when you access the site, it still has most of the materials, including videos, available.

12.3.2 Open research

Governments in some countries such as the USA, Canada and the United Kingdom are requiring all research published as a result of government funding to be openly accessible in a digital format. In Canada, the Minister of State for Science and Technology announced (February 27, 2015) that:

The harmonized Tri-Agency Open Access Policy on Publications requires all peer-reviewed journal publications funded by one of the three federal granting agencies to be freely available online within 12 months.

Also in Canada, Supreme Court decisions and new legislation in 2014 means that it is much easier to access and use free of charge online materials for educational purposes, although there are still some restrictions.

Commercial publishers, who have dominated the market for academic journals, are understandably fighting back. Where an academic journal has a high reputation and hence carries substantial weight in the assessment of research publications, publishers are charging researchers for making the research openly available. The kudos of publishing in an established journal acts as a disincentive for researchers to publish in less prestigious open journals without having to pay to get published.

However, it can only be a question of time before academics fight back against this system, by establishing their own peer reviewed journals that will be perceived to be of the highest standard by the quality of the papers and the status of the researchers publishing in such journals. Once again, though, open research publishing will flourish only by meeting the highest standards of peer review and quality research, by finding a sustainable business model, and by researchers themselves taking control over the publishing process.

Over time, therefore, we can expect nearly all academic research in journals to become openly available.

12.3.3 Open data

The two main sources of open data are from science and government. Following an intense discussion with data-producing institutions in member states, the OECD published in 2007 the OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public Funding. In science, the Human Genome Project is perhaps the best example of open data, and several national or provincial governments have created web sites to distribute a portion of the data they collect, such as the B.C. Data Catalogue in Canada.

Again, increasing amounts of important data are becoming openly available, providing more resources with high potential for learning.

The significance for teaching and learning of the developments in open access, OER, open textbooks and open data will be explored more fully in the next section.

References

Bates, T. (2015) Writing an online, open textbook: is it worth it? Online Learning and Distance Education Resources, June 10

Beattie, E. (2018) Open textbooks make education more accessible and affordable, BCcampus, June 7

Caulfield, M. (2015) Asking What Students Spend on Textbooks Is the Wrong Question, Hapgood, November 9

Donaldson, R., Opper, J. and Sen, E. (2019) 2019 Florida Student Textbook and Course Materials Survey Tallahassee: Florida Virtual Campus

Donovan, T. et al. (2018) Tracking Online and Distance Education in Canadian Universities and Colleges: 2018 Halifax NS: Canadian Digital Learning Research Association

Hill, P. (2015) How Much Do College Students Actually Pay For Textbooks? e-Literate, March 25

Jhangiani, R. and Jhangiani, S. (2017) Investigating the Perceptions, Use, and Impact of Open Textbooks: A survey of Post-Secondary Students in British Columbia International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, Vol. 18, No.4

Murphy, E. (2013) Day 2 panel discussion Vancouver BC: COHERE 2013 conference

OECD (2017) OECD Principles and Guidelines for Access to Research Data from Public Funding Paris FR: OECD

Activity 12.3 Using other open resources

1. Check with OpenStax College, the Open Academics Textbook Catalog and the B.C. open textbook project to see if there are any suitable open textbooks for your subject.

2. What open research journals are there in your subject area? (The help of a librarian may be useful here.) Are the articles of good quality? Could your students use these if they were conducting research in this area?

3. Ask your librarian for help in looking for open data sites that might have useful data that you could use in your teaching. Would students be able to find these data sites by themselves, with just a little guidance (for instance, using Google Search for ‘topic + open access’? How could they or you use this open data in their learning?

There is no feedback from me for this activity.