42

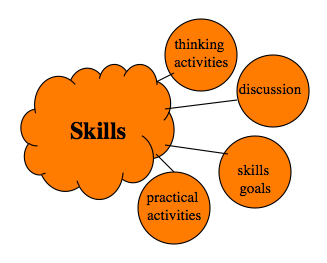

6.5.1 Skills in a digital age

In Chapter 1, Section 1.2, I listed some of the skills that graduates need in a digital age, and argued that consequently a greater focus is now needed on developing such skills, at all levels of education, but particularly at a post-secondary level, where the focus is often on specialised content. Although skills such as critical thinking, problem solving and creative thinking have always been valued in higher education, the identification and development of such skills is often implicit and almost accidental, as if students will somehow pick up these skills from observing faculty themselves demonstrating such skills or through some form of osmosis resulting from the study of content.

It is of course somewhat artificial to separate content from skills, because content is the fuel that drives the development of intellectual skills. My aim here is not to downplay the importance of content, but to ensure that skills development receives as much focus and attention from instructors, and that we approach intellectual skills development in the same rigorous and explicit way as apprentices are trained in manual skills.

6.5.2 Setting goals for skills development

Thus a critical step is to be explicit about what skills a particular course or program is trying to develop, and to define these goals in such a way that they can be implemented and assessed. In other words it is not enough to say that a course aims to develop critical thinking, but to state clearly what this would look like in the context of the particular course or content area, in ways that are clear to students. In particular skills should be defined in such a way that they can be assessed, and students should be aware of the criteria or rubrics that will be used for assessment. Skills development is discussed throughout the book, but particularly in:

6.5.3 Thinking activities

These include activities that enable students to practice a range of skills, such as critical thinking, problem solving, and decision-making. A skill is not binary, in the sense that you either have it or you don’t. There is a tendency to talk about skills and competencies in terms of novice, intermediate, expert, and master, but in reality skills require constant practice and application and there is, at least with regard to intellectual skills, no final destination. With practice and experience, for instance, our critical thinking skills should be much better at 65 than at 25 (although some might call that ‘wisdom’).

A major challenge over a full program is to ensure a steady progression in the level of a skill, so, for instance, a student’s critical thinking skills are better when they graduate than when they started the program. This means identifying what level of skill they have before entering a course, as well as measuring it when they leave. So it is critically important when designing a course or program to design activities that require students to develop, practice and apply thinking skills on a continuous basis, preferably in a way that starts with small steps and leads eventually to larger ones.

There are many ways in which intellectual skills can be developed and assessed, such as written assignments, project work, and focused discussion, but these thinking activities need to be designed, then implemented, on a consistent basis by the instructor.

6.5.4 Practical activities

It is a given in vocational programs that students need lots of practical activities to develop their manual skills. This though is equally true for intellectual skills. Students need to be able to demonstrate where they are along the road to mastery, get feedback on it, and retry as a result. This means doing work that enables them to practice specific skills.

In the history scenario (Scenario D), students had to cover and understand the essential content in the first three weeks, do research in a group, develop an agreed project report, in the form of an e-portfolio, share it with other students and the instructor for comments, feedback and assessment, and present their report orally and online. Ideally, they will have the opportunity to carry over many of these skills into other courses where the skills can be further refined and developed. Thus, with skills development, a longer term horizon than a single course will be necessary, so integrated program as well as course planning is important.

6.5.5 Discussion as a tool for developing intellectual skills

Discussion is a very important tool for developing thinking skills. However, not any kind of discussion. It was argued in Chapter 2 that academic knowledge requires a different kind of thinking to everyday thinking. It usually requires students to see the world differently, in terms of underlying principles, abstractions and ideas.

Thus discussion needs to be carefully managed by the instructor, so that it focuses on the development of skills in thinking that are integral to the area of study. This requires the instructor to plan, structure and support discussion within the class, keeping the discussions in focus, and providing opportunities to demonstrate how experts in the field approach topics under discussion, and comparing students’ efforts. The role of discussion is covered more fully in Chapter 3, Section 4, Chapter 4, Section 4 and Chapter 12, Section 10.

6.5.6 In conclusion

There are many opportunities in even the most academic courses to develop intellectual and practical skills that will carry over into work and life activities in a digital age, without corrupting the values or standards of academia. Even in vocational courses, students need opportunities to practice intellectual or conceptual skills such as problem-solving, communication skills, and collaborative learning. However, this won’t happen merely through the delivery of content. Instructors need to:

- think carefully about exactly what skills their students need;

- how this fits with the nature of the subject matter;

- the kind of activities that will allow students to develop and improve their intellectual skills;

- how to give feedback and to assess those skills, within the time and resources available.

This is a very brief discussion of how and why skills development should be an integral part of any learning environment.

Activity 6.5 Developing skills

- Returning to the HIST 305 scenario, what specific skills was Ralph Goodyear trying to develop in his course?

- Are the skills being developed by students in the history scenario relevant to a digital age?

- Is this section likely to change the way you think about teaching your subject, or do you already cover skills development adequately? If you feel you do cover skills development well, does your approach differ from mine?

For feedback in the first two questions, click on the podcast below.