104

Image: Care2, 2012

Some methods of teaching, such as online collaborative learning (Chapter 4, Section 4), depend on high quality discussion between instructor and students. However, there is substantial research evidence to suggest that ongoing, continuing communication between teacher/instructor and students is essential in all online learning. At the same time it needs to be carefully managed in order to control the teacher/instructor’s workload.

13.10.1 The concept of ‘teacher presence’

In a classroom environment, the presence of the teacher or instructor is taken for granted. Usually, the teacher is at the front of the class and at the centre of attention. Students may want to ignore a teacher but that is not always easy to do, even in a very large lecture theatre. The instructor just being there in the room is often considered to be enough. We can learn a lot though about the important pedagogical aspects of teacher presence from the research into online learning, where teacher or instructor presence has to be worked at.

13.10.2 Teacher presence and the loneliness of the long distance learner

Research has clearly indicated that ‘perceived instructor presence’ is a critical factor for online student success and satisfaction (Jonassen et al., 1995; Anderson et al., 2001; Garrison and Cleveland-Innes, 2005; Baker, 2010; Sheridan and Kelly, 2010). Students need to know that the teacher or instructor is following the online activities of students and that the teacher/instructor is actively participating during the delivery of the course.

The reasons for this are obvious. Online students often study from home, and if they are fully online may never meet another student on the same course. They do not get the important non-verbal cues from the teacher/instructor or other students, such as the stare at a stupid question, the intensity in presentation that shows the passion of the instructor for the topic, the ‘throwaway’ comment that indicates the instructor doesn’t have much time for a particular idea, or the nodding of other students’ heads when another student makes a good point or asks a pertinent question. An online student does not have the opportunity for a spontaneous discussion by bumping into the teacher or instructor in the corridor.

However, a skilled teacher can create just as compelling a learning environment online, but it needs to be deliberately planned and designed, and be done in such a way that the their workload can be controlled.

13.10.3 Setting students’ expectations

It is essential right at the start of a course for the teacher or instructor to make it clear to students what is expected of them when they are studying online, whether in a blended or fully online course. (On reflection, why would we not do the same for face-to-face teaching?)

Most institutions have a code of behaviour for the use of computers and the Internet, but these are often lengthy documents written in a bureaucratic language, and are more concerned with spam, general online behaviour such as ‘flaming’ or bullying, or hacking. Although necessary, this is not sufficient for teaching purposes. Thus teachers or instructors are advised to develop a set of specific requirements for student behaviour that is related to the needs of the particular course, and deals with the academic requirements of studying online. Some guidelines or principles for developing meaningful online discussion can found in Chapter 4, Section 4.4.4. However, there are some other specific actions that teachers and instructors can take to ensure teacher presence.

A small task can be set in the first week of a course that sets up student expectations for the rest of the course. For instance students can be asked to post their bio and respond to other students bio posts, or can be asked to comment on a topic related to the course and their views on this before the course really begins, using the discussion forum facility in the learning management system. It is important to pay particular attention to this activity, because research indicates that online students who do not respond to set activities in the first week are at high risk of non-completion. Teachers or instructors should follow up with a phone call or e-mail to non-respondents at the end of the first week, and ensure that each student is following the guidelines or doing the task set, even if students are experienced in studying online. Students know that the teacher/instructor is then following what they do (or more importantly don’t do) from the outset.

Different courses may require different guidelines. For instance a math or science course may not put so much emphasis on discussion forums, but more on self-assessed computer-marked multiple choice questions. It should be made clear whether students must do these or if they are optional, or how much time should be spent as a minimum on doing such non-graded activities, and the relationship of non-graded activities to activities that are graded or assessed. They should get such an activity within the first week of a course, and the teacher/instructor should follow up with those that avoid the activity or have difficulties with it.

Lastly, teachers/instructors should follow their own guidelines. Your comments should be helpful and constructive, rather than negative. You should actively encourage discussion by being ‘present’ and stepping in on a discussion where necessary – for instance if the comments are getting off topic or too personal.

13.10.4 Teaching philosophy and online communication

Teachers/instructors who have a more objectivist approach to teaching are more likely to focus on whether students are not only covering the necessary content but are also understanding it. This often requires students going back over content, providing misunderstood or difficult content in an alternative manner (e.g. a video as well as text), and instructor or automated (computer-based) feedback. Most LMSs will provide summaries of student activities, and it is important to track each individual student’s progress. Teachers/instructors with a more constructivist approach are more likely to emphasize online discussion and argument.

Whatever your approach, students want to know where you stand on some of the topics. Thus while it is necessary often to present content objectively with an ‘on the one hand… on the other…’ approach, students usually feel more committed to a course where the teacher’s/instructor’s own views or approach to a topic are made clear. This can be done in a variety of ways, such as a podcast on a topic, or an intervention in a discussion, or a short video of how you would go about solving an equation. These personal interventions have to be carefully judged, but can make a big difference to student commitment and participation.

13.10.5 Choice of medium for teacher/instructor communication

There is now a wide variety of media by which teachers/instructors can communicate with students, or students can communicate with each other. Basically, though, they fall into four categories:

- face-to-face, such as set office hours, scheduled classes or serendipity (bumping into each other in the corridor);

- synchronous communication media, including voice phone calls, text and audio conferencing over the web (for example, Blackboard Collaborate), or even video-conferencing (for example, ZOOM);

- asynchronous communication media, including e-mail, podcasts or recorded video clips, and online discussion forums within an LMS;

- social media, such as blogs, wikis, text or voice messages on mobile phones, Facebook and Twitter.

In general, I much prefer asynchronous communication for two reasons. Online or even on-campus, nominally full-time students are often working and have busy lives; asynchronous discussion, questions and answers are more convenient for them. Asynchronous communications can be accessed at any time. Also, they are much more convenient for me as a teacher or instructor. For instance I can go to a conference even in another country yet still log on to my course when I have some free time. I also have a record of what I have said to students. If using an LMS, it is password protected and communications can be kept within the class group.

However, asynchronous communication can be frustrating for students when complex decisions need to be made within a tight timescale, such as deciding the roles and responsibilities for group work, the final draft of a group assignment, or a student’s lack of understanding that is blocking any further progress on the topic. Then face-to-face or technology-based synchronous communication is better, depending on whether it is a blended or fully online course.

In a fully online course, I also sometimes use a conferencing system such as ZOOM to bring all the students together once or twice during a semester, to get a feeling of community at the start of a course, to establish my ‘presence’ as a real person with a face or voice at the start of a course, or to wrap up a course at the end, and I try to provide plenty of opportunity for questions and discussion by the students themselves. However, these synchronous ‘lectures’ are always optional as there will always be some students who cannot be present (although they can be made available in recorded format).

For a blended course, though, I would organise a series of relatively small face-to-face group sessions in the first or second week of a course, so students can get to know each other as well as me, then keep them in the same groups online for any group work or discussions.

Blogs or e-portfolios can be used by students to record their learning or to reflect on what they have learned, and blogs can be a useful way for the instructor to comment on news or events relevant to a course, but care is needed to keep a clear separation between students’ private lives and conversations, and the more formal in-class communications.

13.10.6 Managing online discussion

Whole books have been written on this topic (see Salmon, 2000, Paloff and Pratt, 2007; Harasim, 2017) and this is discussed in detail in Chapter 4, Section 4.4.4. However, there are some basic guidelines to follow.

13.10.6.1 Threaded discussion

Use the threaded discussion forum facility in the LMS (in some LMSs the instructor has to choose to switch this on).

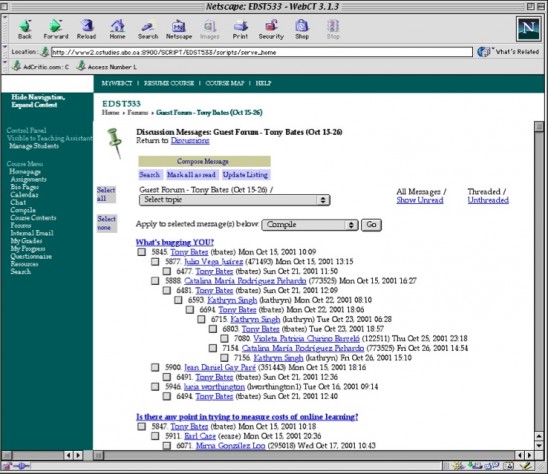

Figure 13.10.2 Example of a threaded discussion topic. This is an old LMS (WebCT) but illustrates clearly the value of a threaded discussion.

Although LMSs are losing some of their original appeal, with more and more instructors using WordPress or other content management systems, I like to use the LMS forum discussion tool because I can organize the discussion by separate topics (a forum for each topic).

In a threaded discussion, a student comment on someone else’s post on a topic is posted next to the post, allowing either the student making the original post or other students to respond to the comment. This way a ‘thread’ of comments linked to a specific topic can be followed. A well chosen topic or sub-topic will often have ten or more threaded comments, and the instructor can tell at a glance which topics have gained ‘traction’.

The alternative, comments posted in time order, as in comments on a blog, for instance, make it difficult to follow a thread of an argument. Also I like to keep a least some of the discussion ‘private’, just between me and the students on the course, as I am using the discussion forum to identify areas of misunderstanding and to develop skills such as critical thinking and clear communication.

13.10.6.2 Be there!

By that I mean ensure that students are aware of your regular online presence. This means monitoring the discussions on a regular basis, and occasionally intervening when appropriate, without hogging the discussion.

For more guidance on handling online communication with students, take a look particularly at the books by Gilly Salmon, Rena Paloff and Keith Pratt, and Linda Harasim in the references below.

13.10.7 Cultural and other student differences

The most interesting and exciting online courses that I have taught have included a wide range of international students from different countries. However, even if all the students are within one hour’s commute of the institution, they will have different learning styles and approaches to studying online. This is why it is important to be clear about the desired learning outcomes, and the goals for discussion forums.

Students learn in different ways. If one of the desired learning outcomes is critical thinking, students can achieve that in different ways. Some may prefer to discuss course issues with other students over a coffee. Some may do a lot of reading, seeking out different viewpoints. Others may prefer to work mainly in the online discussion forums. Some students learn a lot by lurking online but never contribute directly. Now if you are trying to improve international students’ language skills, then you may require them to participate in the online discussions, and will assess them on their contributions. However, I try not force students to participate. I see it as my challenge to make the topic interesting enough to draw them in. I don’t really care how they achieve the learning outcomes so long as they do.

Having said that, much can be done to facilitate or encourage students to participate. I taught one graduate course where I had about 20 of the 30 students in my class with Chinese surnames. From the student records and the short bios they posted I noted that a few students were from the Chinese mainland, several more were living in Hong Kong, and the rest had Canadian addresses. However even the latter consisted of two quite different groups: recent immigrants to Canada, and at least one student whose great grandfather had been one of the first immigrants to Canada in the 19th century.

Although it is dangerous to rely on stereotypes, I noticed that the further away ‘psychologically’ or geographically the student was, the less they were initially inclined to participate online. This was partly a language issue but also a cultural issue. The mainland Chinese in particular were very reluctant to post comments. Fortunately we had a visiting Chinese scholar with us and she advised us to get the three mainland Chinese women on the course to develop a collective contribution to the discussion and then ask them to send it to me to check that it was ‘appropriate’ before they posted. I made a few comments then sent it back and they then posted it. Gradually by the end of the course they each had the confidence to post individually their own comments. But it was a difficult process for them. (On the other hand, I had Mexican students who commented on everything, whether it was about the course or not, and especially about the World Cup soccer tournament that was on at the time).

Students differences (and possibly stereotypes) also change over time. I am not sure whether 20 years later the differences would apply to students with Chinese names today. The important point is that different students respond differently to online discussion and the instructor needs sensitivity to these differences, and strategies to ensure participation from everyone.

13.10.8 Conclusion

This is a big topic and difficult to cover adequately in one section. However, the importance of teacher/instructor presence cannot be overemphasized for getting students successfully to complete any course with an online component. The lack of instructor online presence in xMOOCs is one reason so few students complete the courses.

There is an unlimited number of ways in which you, as a teacher or instructor, can communicate now with students, but it is also essential at the same time to control your workload. You cannot be available 24×7, and this means designing the online delivery in such a way that your ‘presence’ is used to best effect. At the same time, communication with online students can end up being the most interesting and satisfying part of teaching.

References and further reading

(This is just a small sample of many publications on this topic,)

Anderson, T., Rourke, L., Garrison, R., & Archer, W. (2001). Assessing teaching presence in a computer conferencing context Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, Vol. 5, No.2.

Baker, C. (2010) The Impact of Instructor Immediacy and Presence for Online Student Affective Learning, Cognition, and Motivation The Journal of Educators Online Vol. 7, No. 1

Garrison, D. R. & Cleveland-Innes, M. (2005). Facilitating cognitive presence in online learning: Interaction is not enough American Journal of Distance Education, Vol. 19, No. 3

Harasim, L. (2017) Learning Theory and Online Technologies 2nd edition New York/London: Taylor and Francis

Jonassen, D., Davidson, M., Collins, M., Campbell, J. and Haag, B. (1995) ‘Constructivism and Computer-mediated Communication in Distance Education’, American Journal of Distance Education, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp 7-26.

Paloff, R. and Pratt, K. (2007) Building Online Learning Communities San Francisco: John Wiley and Co.

Salmon, G. (2000) E-moderating London/New York: Taylor and Francis

Sheridan, K. and Kelly, M. (2010) The Indicators of Instructor Presence that are Important to Students in Online Courses MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, Vol. 6, No. 4

Activity 13.10 Communicating with your students

1. How could you apply some of the principles of teacher presence in an online course to a large lecture class?

2. In a blended class where students have at least one classroom session once a week, how would you decide what interactions with students should be done on campus, and what online? What are the reasons for your decision? Does it matter?

3. How important is student discussion in your subject area? What learning goals does it support? How can you help students to achieve these goals through discussion?

4. Interaction/communication between students and teachers/instructors is one of the main cost drivers of education. Could the goals that justify the use of discussion or other forms of communication between learners and teachers or instructors be achieved in other, less costly, ways? Could this be replaced by computers, for instance? If not, why not?

For feedback on this activity, click on the podcast below: