87

Analysing student demographics may help to decide whether or not a course or program should be either campus-based or fully online, but we need to consider more than just student demographics to make the decision about what to do online and what to do on campus for the majority of campus-based courses and programs that will increasingly have an online component.

11.4.1 A suggested method

11.4.1.1 Finding an approach based on successful experience

It should be stated up front that there is no generally agreed theory or even best practices for making this decision. The default mode has been that face-to-face teaching must be inherently superior, and you only go online if you must. However, we have seen that online learning has over the last ten years or so demonstrated clearly that many areas of knowledge can be taught just as well or better online. I will look therefore to examples where there has been a conscious decision to identify the relative affordances of different media, including face-to-face teaching. The area where this becomes most clear is in the teaching of science.

I am going to draw on a method used initially at the U.K. Open University for designing distance education courses and programs in science in the 1970s. The challenge was to decide what was best done in print, on television, via home experiment kits, and finally in a one week residential hands-on summer school at a traditional university. Since then, Dietmar Kennepohl and Lawton Shaw, of Athabasca University, have edited an excellent book about teaching science online (Kennepohl and Shaw, 2010). Also, the Colorado Community College System has used a combination of remotely operated labs for student practical work, combined with home kits, for teaching online introductory science courses (Schmidt and Shea, 2015).

Each of these initiatives has adopted a pragmatic method for making decisions about what must be done face-to-face and what can be done online. What each of these approaches had in common was trusting the knowledge and experience of subject experts who are willing to approach this question in an open-minded way, and working with instructional designers or media producers on an equal footing.

From these experiences, I have extracted one possible process for determining when to go online and when not to, on purely pedagogical grounds, for a course that is being designed from scratch in a blended delivery mode. It is based on a five step process:

- identify the overall instructional approach/pedagogy required

- identify the main content to be covered

- identify the main skills to be taught

- analyse the resources available

- analyse the most appropriate mode of delivery for each of the learning objectives identified above

I will choose a subject area at random: hematology (the study of blood), in which I am not an expert. But here’s what I would suggest if I was working with a subject specialist in this area.

The example in this section is drawn from higher education, but a similar approach could be followed in the k-12 system. The main challenge for teachers will be resources (see 11.4.2 below), but the approach, the way of thinking about making decisions, should still work when teaching school children.

11.4.1.2 Step 1: identify the main instructional approach.

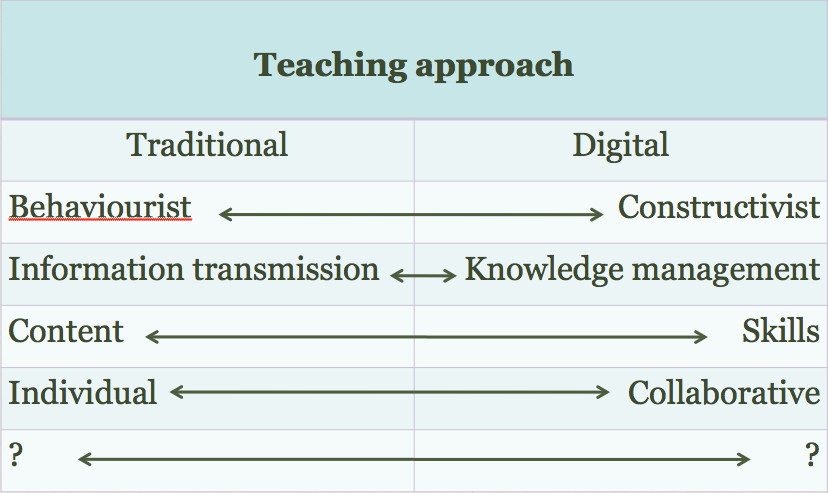

This is discussed in some detail in Chapters 2 to 4, but here are the kinds of decision to be considered:

This should lead to a general plan or approach to teaching that identifies the teaching methods to be used in some detail. In the example of hematology, the instructor wants to take a more constructivist approach, with students developing a critical approach to the subject matter. In particular, she wants to relate the course specifically to certain issues, such as security in handling and storing blood, factors in blood contamination, and developing student skills in analysis and interpretation of blood samples.

11.4.1.3 Step 2. Identify the main content to be covered

Content covers facts, data, hypotheses, ideas, arguments, evidence, and description of things (for instance, showing or describing the parts of a piece of equipment and their relationship). What do they need to know in this course? In hematology, this will mean understanding the chemical composition of blood, what its functions are, how it circulates through the body, descriptions of the relevant parts of cell biology, what external factors may weaken its integrity or functionality, the equipment used to analyse blood and how the equipment works, principles, theories and hypotheses about blood clotting, the relationship between blood tests and diseases or other illnesses, and so on.

In particular, what are the presentational requirements of the content in this course? Dynamic activities need to be explained, and representing key concepts in colour will almost certainly be valuable. Observations of blood samples under many degrees of magnitude will be essential, which will require the use of a microscope.

There are now many ways to represent content: text, graphics, audio, video and simulations. For instance, graphics, a short video clip, or photographs down a microscope can show examples of blood cells in different conditions. Increasingly this content is already available over the web for free educational use (for instance, see the American Society of Hematology’s video library). Creating such material from scratch is more expensive, but is becoming increasingly easy to do with high quality, low cost digital recording equipment. Using a carefully recorded video of an experiment will often provide a better view than students will get crowding around awkward lab equipment.

11.4.1.4 Step 3. Identify the main skills to be developed during the course

Skills describe how content will be applied and practiced. This might include analysis of the components of blood, such as the glucose and insulin levels, the use of equipment (where ability to use equipment safely and effectively is a desired learning outcome), diagnosis, interpreting results by making hypotheses about cause and effect based on theory and evidence, problem-solving, and report writing.

Developing skills online can be more of a challenge, particularly if it requires manipulation of equipment and a ‘feel’ for how equipment works, or similar skills that require tactile sense. (The same could be said of skills that require taste or smell). In our hematology example, some of the skills that need to be taught might include the ability to analyse analytes or particular components of blood, such as insulin or glucose, to interpret results, and to suggest treatment. The aim here would be to see if there are ways these skills can also be taught effectively online. This would mean identifying the skills needed, working out how to develop such skills (including opportunities for practice) online, and how to assess such skills online.

Let’s call Steps 2 and 3 the key learning objectives for the course.

11.4.1.5 Step 4: Analyse the most appropriate mode for each learning objective

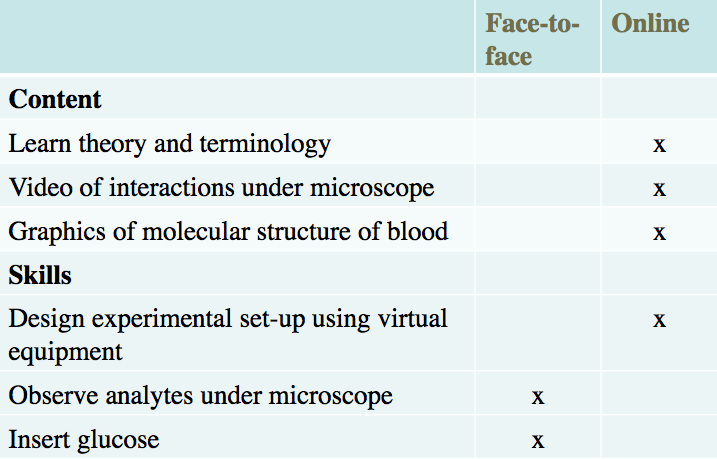

Then create a table as in Figure 11.4.4:

In this example, the instructor is keen to move as much as possible online, so she can spend as much time as possible with students, dealing with laboratory work and answering questions about theory and practice. She was able to find some excellent online videos of several of the key interactions between blood and other factors, and she was also able to find some suitable graphics and simple animations of the molecular structure of blood which she could adapt, as well as creating with the help of a graphics designer her own graphics. Indeed, she found she had to create relatively little new material or content herself.

The instructional designer also found some software that enabled students to design their own laboratory set-up for certain elements of blood testing which involved combining virtual equipment, entering data values and running an experiment. However, there were still some skills that needed to be done hands-on in the laboratory, such as inserting glucose and using a ‘real’ microscope to analyse the chemical components of blood. However, the online material enabled the instructor to spend more time in the lab with students.

It can be seen in this example that most of the content can be delivered online, together with a critically important skill of designing an experiment, but some activities still need to be done ‘hands-on’. This might require one or more evening or weekend sessions in a lab for hands-on work, thus delivering most of the course online, or there may be so much hands-on work that the course may have to be a hybrid of 50 per cent hands-on lab work and 50 per cent online learning.

With the development of animations, simulations and online remote labs, where actual equipment can be remotely manipulated, it is becoming increasingly possible to move even traditional lab work online. At the same time, it is not always possible to find exactly what one needs online, although this will improve over time. In other subject areas such as humanities, social sciences, and business, it is much easier to move the teaching online.

This is a crude method of determining the balance between face-to-face teaching and online learning for a blended learning course, but at least it’s a start. It can be seen that these decisions have to be relatively intuitive, based on instructors’ knowledge of the subject area and their ability to think creatively about how to achieve learning outcomes online. However, we have enough experience now of teaching online to know that in most subject areas, a great deal of the skills and content needed to achieve quality learning outcomes can be taught online. It is no longer possible to argue that the default decision must always be to do the teaching in a face-to-face manner.

Thus every instructor now needs to ask the question: if I can move most of my teaching online, what are the unique benefits of the campus experience that I need to bring into my face-to-face teaching? Why do students have to be here in front of me, and when they are here, am I using the time to best advantage?

11.4.2 Analyse the resources available

There is one more consideration besides the type of learners, the overall teaching method, and making decisions based on pedagogical grounds, and that is to consider the resources available.

11.4.2.1 The time of the teacher or instructor

In particular, the key resource is the time of the teacher or instructor. Careful consideration is needed about how best to spend the limited time available. It may be all very well to identify a series of videos as the best way to capture some of the procedures for blood testing, but if these videos do not already exist in a format that can be freely used, shooting video specially for this one course may not be justified, in terms of either the time the teacher or instructor would need to spend on video production, or the costs of making the videos with a professional crew.

Time to learn how to do online teaching is especially important. There is a steep learning curve and the first time will take much longer than subsequent online courses. Some form of training or professional development for teachers or instructors thinking of moving online or into blended learning is needed before they embark on blended or online learning. Sometimes in post-secondary education instructors can get some release time (up to one semester from one class) in order to do the design and preparation for an online course, or a re-designed hybrid course. This however is not always possible, but one thing we do know. Teacher or instructor workload is a function of course design. Well designed online courses should require less rather than more work from an instructor.

11.4.2.2. Learning technology support staff.

If your institution has a service unit for faculty development and training, instructional designers and web designers for supporting teaching, use them. Such staff are often qualified in both educational sciences and computer technology. They have unique knowledge and skills that can make your life much easier when teaching online. (This will be discussed further in Chapter 14.)

The availability and skill level of learning technology support from the institution or school board is a critical factor. Can you get the support of an instructional designer and media producers? If not, it is likely that much more will be done face-to-face than online, unless you are already very experienced in online learning.

11.4.2.3 Readily available technology

Most institutions and increasingly most school districts now have a learning management system such as Brightspace or Moodle, or a video-conferencing system for transmitting or recording lessons. But increasingly, instructors in post-secondary education will need access to media producers who can create videos, digital graphics, animations, simulations, web sites, and access to blog and wiki software. Without access to such technology support, instructors are more likely to fall back on tried and true classroom teaching.

11.4.2.4 Colleagues experienced in blended and online learning

It really helps if there are experienced colleagues in the school or department who understand the subject discipline and have done some online teaching. They will perhaps even have some materials already developed, such as graphics, that they will be willing to share.

11.4.2.5 Money

Are there resources available to buy you out for one semester to spend time on course design? Many post-secondary institutions have development funds for innovative teaching and learning, and there may be external grants for creating new open educational resources, for instance. This will increase the practicality and hence the likelihood of more of the teaching moving online.

We shall see that as more and more learning material becomes available as open educational resources, teachers and instructors will be freed up from mainly content presentation to focusing on more interaction with students, both online and face to face. However, although open educational resources are becoming increasingly available, they may not exist in the topics required or they may not be of adequate quality in terms of either content or production standards (see Chapter 12.2 for more on OERs).

The extent to which these resources are available will help inform you on the extent to which you will be able to go online and meet quality standards. In particular, you should think twice about going online if none of the resources listed above is going to be available to you.

11.4.3 The case for multiple modes

Increasingly, it is becoming difficult to separate markets for particular courses or programs. Although the majority of students taking a first year university course are likely to be coming straight from high school, some will not. There may be a minority of students who left high school directly for work, or went to a two year college to get vocational training, but now find they need a degree. Especially in professional graduate programs, students may be a mix of those who have just completed their bachelor’s course and are still full-time students, and those that are already in the work-force but need the specialist qualification. There will be a mix of students in third and fourth year undergraduate courses, some of whom will be working over 15 hours a week, and others who are studying more or less full time. In theory, then, it may be possible to identify a particular market for mainly face-to-face, blended or fully online learning, but in practice most courses are likely to have a mix of students with different needs.

If, though, as seems likely, more and more courses will end up as blended learning, then it is worth thinking about how courses could be designed to serve multiple markets. For instance, if we take our hematology course, it could be offered to full-time third year undergraduate students studying biology, or it could also be offered either on its own or with other related courses as a certificate in blood management for nurses working in hospitals. It might also be useful for students studying medicine who have not taken this particular course as an undergraduate, or even for patients with conditions related to their blood levels, such as diabetes.

If for instance our instructor developed a course where students spent approximately 50 per cent of their time online and the rest on campus, it may eventually be possible to design this for other markets as well, with perhaps practical work for nurses being done in the hospital under supervision, or just the online part being offered as a short MOOC for patients. For some courses (perhaps not hematology), it may be possible to offer the course wholly online, in blended format or wholly face-to-face. This would allow the same course to reach several different markets.

11.4.4 Questions for consideration in choosing modes of delivery

In summary, here are some questions to consider, when designing a course from scratch:

1. What kind of learners are likely to take this course? What are their needs? Which mode(s) of delivery will be most appropriate to these kinds of learners? Could I reach more or different types of learners by choosing a particular mode of delivery?

2. What is my view of how learners can best learn on this course? What is my preferred method(s) of teaching to facilitate that kind of learning on this course?

3. What is the main content (facts, theory, data, processes) that needs to be covered on this course? How will I assess understanding of this content?

4. What are the main skills that learners will need to develop on this course? What are the ways in which they can develop/practice these skills? How will I assess these skills?

5. How can technology help with the presentation of content on this course?

6. How can technology help with the development of skills on this course?

7. When I list the content and skills to be taught, which of these could be taught:

- fully online

- partly online and partly face-to-face

- can only be taught face-to-face?

8. What resources do I have available for this course in terms of:

- professional help from instructional designers and media producers;

- possible sources of funding for release time and media production;

- good quality open educational resources.

9. What kind of classroom space will I need to teach the way I wish? Can I adapt existing spaces or will I need to press for major changes to be made before I can teach the way I want to?

10. In the light of the answers to all these questions, which mode of delivery makes most sense?

References

Kennepohl, D. and Shaw, L. (eds.) (2010) Accessible Elements: Teaching Science Online and at a Distance Athabasca AB: Athabasca University Press

Schmidt, S. and Shea, P. (2015) NANSLO Web-based Labs: Real Equipment, Real Data, Real People! WCET Frontiers

Activity 11.4 Deciding on the mode of delivery

1. Try following the process above for a possible new course that you would like to teach or for revising a course you are already teaching.

There is no feedback on this activity.