84

In Chapters 7 to 10, the use of media incorporated into a particular course or program was explored. In Chapter 12 the focus will be on deciding when and how to adopt an approach that incorporates ‘open-ness’ in its design and delivery. In this chapter, the focus is on deciding whether a whole course or program should be offered partly or wholly online.

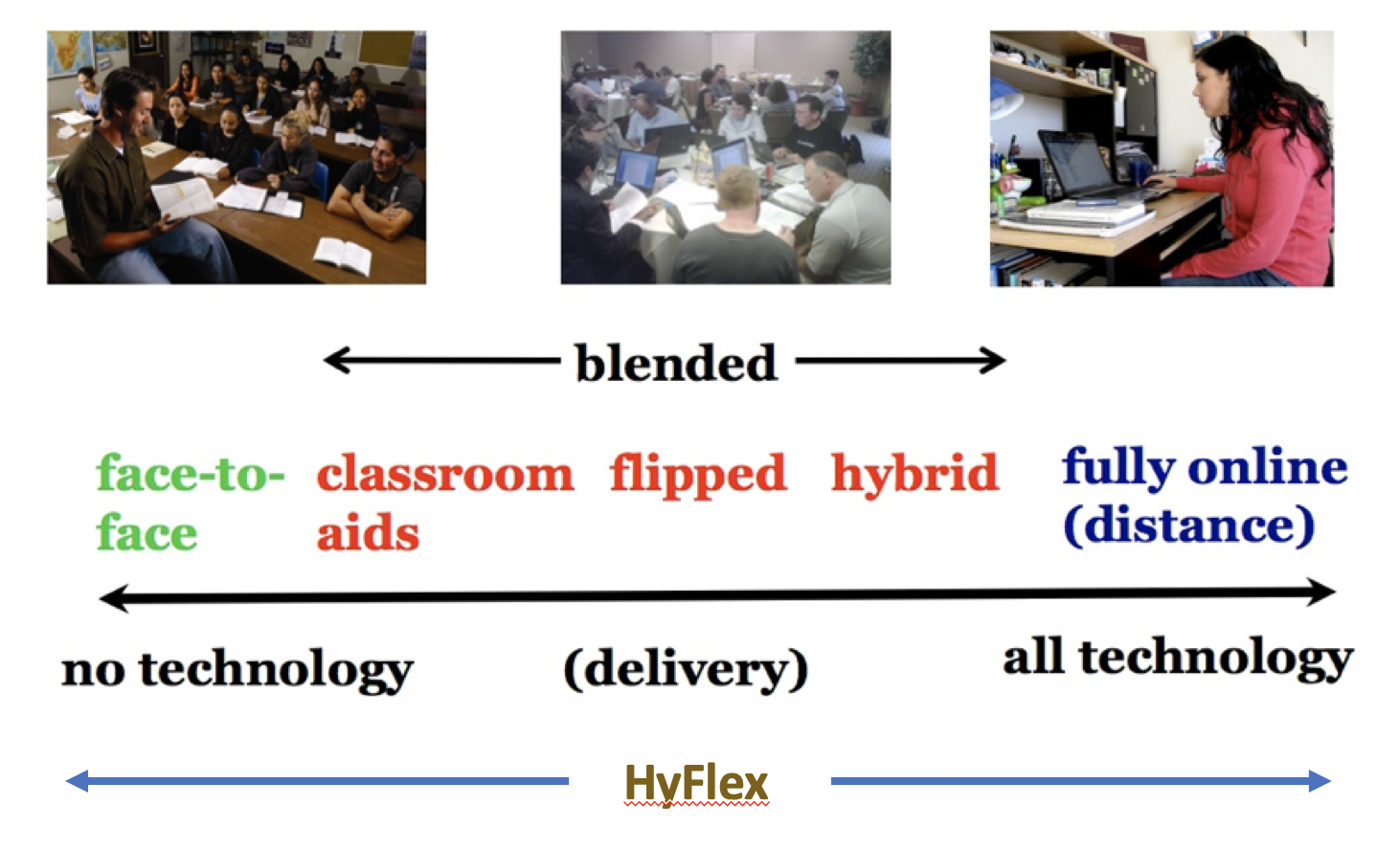

11.1.1 The continuum of digital learning

Until quite recently, there were two distinct methods of delivering educational courses:

- in-person, on-campus teaching, in both schools and post-secondary educational institutions

- fully distance, where students did not come to campus but studied generally at home.

Now, however, with the development of online and digital learning, there is a wide variety of ways in which to study. Indeed there is a continuum of technology-based learning:

Online learning, blended learning, flipped learning, hybrid learning, flexible learning, hyflex learning, open learning and distance education are all terms that are often used interchangeably, but there are significant differences in meaning. At the time of writing it is possible to identify at least the following modes of delivery:

11.1.2 Classroom teaching

This is teaching where no technology at all is used, which is very rare these days. Indeed it could be argued that desks, blackboards, and classrooms are just one form of technology. However, that technology was pre-digital.

11.1.2.1 Digital classroom aids

This is technology used as classroom aids; typical examples are the use of an overhead projector or a video shown in a classroom, or Powerpoint slides and/or clickers in a lecture. These digital technologies enhance the traditional teaching method but do not change it (substitution or augmentation, in the SAMR model).

11.1.3 Blended learning

Blended learning encompasses a wide variety of designs:

- the use of a learning management system to support classroom teaching, for storing learning materials, providing a course schedule of topics, for online discussion, and for submitting student assignments, but teaching is still delivered mainly through classroom sessions;

- the use of lecture capture for flipped classrooms, where students watch the lecture via streamed video then come to class for discussion or other work; see for instance a calculus course offered at Queen’s University, Canada;

- alternating or parallel modes: one semester face-to-face on campus and two semesters online (one model at Royal Roads University); in the school system, most courses are on campus but students take can take some courses online;

- hybrid or flexible learning requiring the redesign of teaching so that students can do the majority of their learning online, coming to campus only for very specific face-to-face teaching, such as labs or hands-on practical work, that cannot be done satisfactorily online (for examples, see 11.1.3.1 below);

- hyflex learning: students are given choice in how they participate in the course and engage with material in the mode that works best for them over the course and from session to session (see 11.1.3.2 below).

in 2018, instructors in nearly three–quarters of all Canadian post-secondary institutions and almost 90% of universities were integrating online with classroom teaching. Of the institutions that responded that they were not yet offering blended/hybrid courses, the majority reported that they planned to in the future (Johnson, 2019). Barbour et al. (2021) reported that the vast majority of school jurisdictions in Canada do not formally track participation in blended learning programs.

11.1.3.1 Hybrid learning

There is an important development within blended learning that deserves special mention, and that is the total re-design of campus-based classes that takes greater advantage of the potential of technology, which I call hybrid learning, with online learning combined with focused small group face-to-face interactions or mixing online and physical lab experiences. In such designs, the amount of face-to-face contact time is usually reduced, for instance from three classes a week to one, to allow more time for students to study online, or the time instructors spend in class presenting material is reduced, with the content available online and instructors using their time supporting students’ learning in class.

In hybrid learning the whole learning experience is re-designed, with a transformation of teaching on campus built around the use of technology. For instance:

- Virginia Tech many years ago created a successful program for first and second year math teaching called the Math Emporium, built around 24 x 7 computer-assisted learning supported by ‘roving’ instructors and teaching assistants (Robinson and Moore, 2006). The Math Emporium is still going strong today;

- The University of British Columbia launched in 2013 what it calls a flexible learning initiative focused on developing, delivering, and evaluating learning experiences that promote effective and dramatic improvements in student achievement. Flexible learning enables pedagogical and logistical flexibility so that students have more choice in their learning opportunities, including when, where, and what they want to learn

- the use of lecture capture for flipped classrooms, where students watch the lecture via streamed video then come to class for discussion or other work; see for instance a calculus course offered at Queen’s University, Canada;

- in the school (k-12) system, there are pockets of schools and teachers who have integrated online learning with their classroom teaching (Arnett, 2021). One model is to replace most class lectures and teacher-led direct instruction with online lessons. Students then work through the lessons primarily in class with their teachers on hand to provide support. These schools measure students’ mastery of specific learning objectives to give the students a clearer picture of both their strengths and their areas for growth. It is students’ individual progress, not the semester calendar, that determines when they move on to new material. Teachers allow and encourage students to revise work and repeat assessments until they reach mastery. At the same time, students can outpace the semester calendar if they work hard or if certain concepts come easily to them. This is a hybrid learning version of competency-based learning (see Chapter 4, Section 5).

11.1.3.2 HyFlex learning

This is a recent development (Milman et al., 2020). A HyFlex class makes class meetings and materials available so that students can access them online or in-person, during or after class sessions. All students, regardless of the path taken, should achieve the same learning objectives. In HyFlex courses, students can choose from one of three participation paths:

- participate in face-to-face synchronous class sessions in-person (in a classroom)

- participate in face-to-face class sessions via video conference (e.g., Zoom)

- participate fully asynchronously via an LMS or other asynchronous technology (Columbia University Centre for Teaching and Learning).

11.1.3.3 Summary

Thus ‘blended learning’ can mean minimal rethinking or redesign of classroom teaching, such as the use of classroom aids, or complete redesign as in flexibly designed courses, which aim to identify the unique pedagogical characteristics of face-to-face teaching, with online learning providing flexible access for the rest of the learning.

11.1.4 (Fully) online learning

Fully online learning, with no classroom or on-campus teaching, is one form of distance education, including:

- courses for credit, which will usually cover the same content, skills and assessment as a campus-based version, but are available only to students admitted to a program;

- non-credit courses offered only online, such as courses for continuing professional education;

- fully open courses, such as MOOCs.

More than one third of higher education students in the USA now take at least one fully online course for credit, and about 15 per cent of students are taking only online courses (Seaman et al., 2018). In Canadian post-secondary institutions, approximately eight per cent of all credit course registrations were fully online in 2017 (Donovan et. al., 2018). Enrolments in fully online courses for credit were increasing steadily in both Canada and the USA at a rate between five to ten per cent per annum over the ten years previous to Covid-19.

Based on actual and estimated enrolment data, the number of students engaged in K–12 distance and online learning in 2020-2021 in Canada was 7.3% of the overall K–12 student population (Barbour et al., 2021, p.7), although this varied from province/territory to province/territory, from Alberta with 13.3% to Nunavut with 0.1%.

11.1.5 A rapidly evolving phenomenon

These forms of education, once considered somewhat esoteric and out of the mainstream of conventional education, were increasingly taking on greater significance and in some cases becoming mainstream themselves, before the Covid-19 pandemic hit. The pandemic has merely accelerated these trends (see, for instance, Fayed and Cummings, 2021).

As teachers and instructors become more familiar and confident with online learning and new technologies, there will be more innovation in integrating online and face-to-face teaching. New forms of blended, hybrid and online learning will emerge over time, as instructors, teachers and institutional managers continue to experiment to increase enrolments, improve learning outcomes, and provide greater flexibility for students and instructors. However, what is clear is that the introduction of digital technologies is having a profound effect on not only the delivery but also the design of teaching and learning.

11.1.6 Decisions, decisions!

These developments open up a whole new range of decisions for instructors. Every instructor now needs to decide:

- what kind of course or program should I be offering?

- how do I design or implement such courses?

- what factors should influence this decision?

- what is the role of classroom teaching when students can now increasingly study most things online?

This chapter aims to help you answer these questions.

References

Arnett, T. (2021) A better way to do online learning, Boston Globe, January 13

Barbour, M., LaBonte, R. and Nagle, J. (2021) State of the Nation: K-12 e-Learning in Canada, 2021 edition Halfmoon Bay, BC: The Canadian eLearning Network

Donovan, T. et al. (2018) Tracking Online and Distance Education in Canadian Universities and Colleges: 2018 Halifax NS: Canadian Digital Learning Research Association

Fayed, I. and Cummings, J. (2021) Teaching in the Post Covid 19 Era Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 764 pp

Johnson, N. (2019)Tracking Online Education in Canadian Universities and Colleges: National Survey of Online and Digital Learning 2019 National Report Halifax NS: Canadian Digital Learning Research Association

Milman, N. et al. (2020) 7 things you should know about the HyFlex course model, EDUCAUSE Review, July 7

Robinson, B. and Moore, A. (2006) ‘Chapter 42: Virginia Tech: the Math Emporium’ in Oblinger, D. (ed.), Learning Spaces Boulder CO: EDUCAUSE

Seaman, J., Allen, I., and Seaman, J. (2018) Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States Wellesley MA: The Babson Survey Research Group

Activity 11.1 Where on the continuum are your courses?

1. If you are currently teaching, where on the continuum is each of your courses? How easy is it to decide? Are there factors that make it difficult to decide where on the continuum any of your courses should fit?

2. How was it decided what the mode of delivery would be for the courses you teach? If you decided, what were the reasons for the location of each course on the continuum?

3. Are you happy with the decision(s)?

3. What kind of students do you have in each type of course?

There is no feedback provided on this activity