Ch. 8 Bloom’s Taxonomy

Mary Forehand (The University of Georgia)

Bloom’s Taxonomy is a classification system used to define and distinguish different levels of human cognition—i.e., thinking, learning, and understanding.

Educators have typically used Bloom’s taxonomy to inform or guide the development of assessments (tests and other evaluations of student learning), curriculum (units, lessons, projects, and other learning activities), and instructional methods such as questioning strategies. (Bloom’s Taxonomy, 2014)

Caption: Photograph of Benjamin Bloom’ Image Source: http://redie.uabc.mx/contenido/vol6no2/art-104-spa/bloom.png

Biography

Benjamin Samuel Bloom, one of the greatest minds to influence the field of education, was born on February 21, 1913 in Lansford, Pennsylvania. As a young man, he was already an avid reader and curious researcher. Bloom received both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Pennsylvania State University in 1935. He went on to earn a doctorate’s degree from the University of Chicago in 1942, where he acted as first a staff member of the Board of Examinations (1940-43), then a University Examiner (1943-59), as well as an instructor in the Department of Education, beginning in 1944. In 1970, Bloom was honored with becoming a Charles H. Swift Distinguished Professor at the University of Chicago.

Bloom’s most recognized and highly regarded initial work spawned from his collaboration with his mentor and fellow examiner Ralph W. Tyler and came to be known as Bloom’s Taxonomy. These ideas are highlighted in his third publication, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: Handbook I, The Cognitive Domain. He later wrote a second handbook for the taxonomy in 1964, which focuses on the affective domain. Bloom’s research in early childhood education, published in his 1964 Stability and Change in Human Characteristics sparked widespread interest in children and learning and eventually and directly led to the formation of the Head Start program in America. In all, Bloom wrote or collaborated on eighteen publications from 1948-1993.

Aside from his scholarly contributions to the field of education, Benjamin Bloom was an international activist and educational consultant. In 1957, he traveled to India to conduct workshops on evaluation, which led to great changes in the Indian educational system. He helped create the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement, the IEA, and organized the International Seminar for Advanced Training in Curriculum Development. He developed the Measurement, Evaluation, and Statistical Analysis (MESA) program at eh University of Chicago. He was chairman of both the research and development committees of the College Entrance Examination Board and the president of the American Educational Research Association.

Introduction

One of the basic questions facing educators has always been “Where do we begin in seeking to improve human thinking?” (Houghton, 2004). Fortunately, we do not have to begin from scratch in searching for answers to this complicated question. The Communities Resolving Our Problems (CROP) recommends, “One place to begin is in defining the nature of thinking.

Before we can make it better, we need to know more of what it is” (Houghton, 2004). Benjamin S. Bloom extensively contemplated the nature of thinking, eventually authoring or co-authoring 18 books. According to a biography of Bloom, written by former student Elliot W Eisner, “It was clear that he was in love with the process of finding out, and finding out is what I think he did best. One of Bloom’s great talents was having a nose for what is significant” (2002).

Although it received little attention when first published, Bloom’s Taxonomy has since been translated into 22 languages and is one of the most widely applied and most often cited references in education. (Anderson & Sosniak, 1994, preface), (Houghton, 2004), (Krathwohl, 2002), (oz-TeacherNet, 2001). As of this writing, three other chapters in this e-book make reference to Bloom’s Taxonomy, yet another testament to its relevance.

History

In 1780, Abigail Adams stated, “Learning is not attained by chance; it must be sought for with ardor and attended to with diligence” (quotationspage.com, 2005).

- Learning, teaching, identifying educational goals, and thinking are all complicated concepts interwoven in an intricate web.

Bloom was arduous, diligent, and patient while seeking to demystify these concepts and untangle this web. He made “the improvement of student learning” (Bloom 1971, Preface) the central focus of his life’s work.

Discussions during the 1948 Convention of the American Psychological Association led Bloom to spearhead a group of educators who eventually undertook the ambitious task of classifying educational goals and objectives. Their intent was to develop a method of classification for thinking behaviors that were believed to be important in the processes of learning. Eventually, this framework became a taxonomy of three domains:

|

• The cognitive – knowledge based domain, consisting of six levels • The affective – attitudinal based domain, consisting of five levels, and • The psychomotor – skills based domain, consisting of six levels. |

In 1956, eight years after the group first began, work on the cognitive domain was completed and a handbook commonly referred to as “Bloom’s Taxonomy” was published. This chapter focuses its attention on the cognitive domain.

While Bloom pushed for the use of the term “taxonomy,” others in the group resisted because of the unfamiliarity of the term within educational circles.

Eventually, Bloom prevailed, forever linking his name and the term. The small volume intended for university examiners “has been transformed into a basic reference for all educators worldwide. Unexpectedly, it has been used by curriculum planners, administrators, researchers, and classroom teachers at all levels of education” (Anderson & Sosniak, 1994, p. 1). While it should be noted that other educational taxonomies and hierarchical systems have been developed, it is Bloom’s Taxonomy which remains, even after nearly fifty years, the de facto standard.

What is Bloom’s Taxonomy?

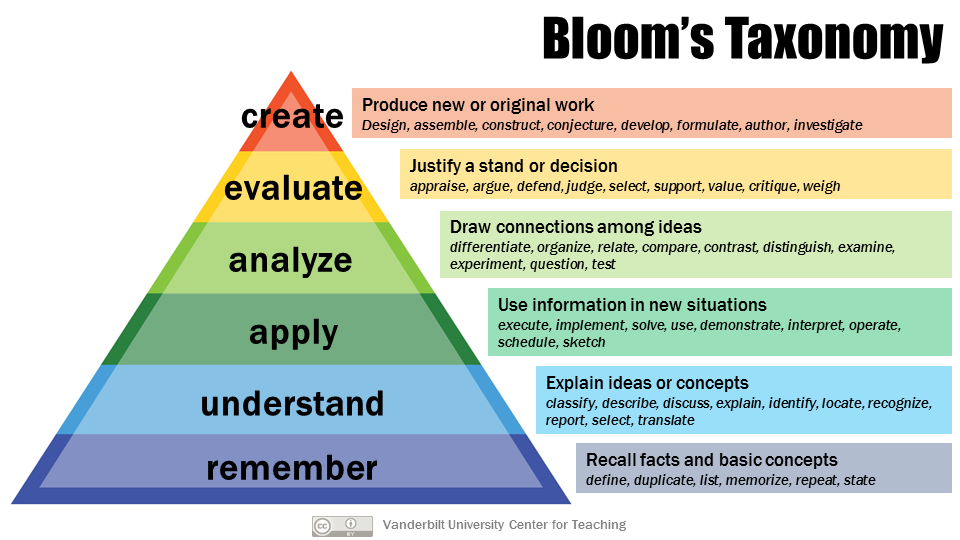

Understanding that “taxonomy” and “classification” are synonymous helps dispel uneasiness with the term. Bloom’s Taxonomy is a multi-tiered model of classifying thinking according to six cognitive levels of complexity. Throughout the years, the levels have often been depicted as a stairway, leading many teachers to encourage their students to “climb to a higher (level of) thought”.

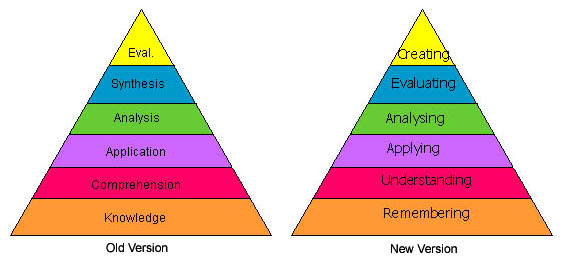

The lowest three levels are: knowledge, comprehension, and application. The highest three levels are: analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. “The taxonomy is hierarchical; [in that] each level is subsumed by the higher levels. In other words, a student functioning at the ‘application’ level has also mastered the material at the ‘knowledge’ and ‘comprehension’ levels.” (UW Teaching Academy, 2003). One can easily see how this arrangement led to natural divisions of lower and higher level thinking.

Clearly, Bloom’s Taxonomy has stood the test of time. Due to its long history and popularity, it has been condensed, expanded, and reinterpreted in a variety of ways. Research findings have led to the discovery of a veritable smörgåsbord of interpretations and applications falling on a continuum ranging from tight overviews to expanded explanations. Nonetheless, one recent revision (designed by one of the co-editors of the original taxonomy along with a former Bloom student) merits particular attention.

Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy (RBT)

During the 1990’s, a former student of Bloom’s, Lorin Anderson, led a new assembly which met for the purpose of updating the taxonomy, hoping to add relevance for 21st century students and teachers. This time “representatives of three groups [were present]: cognitive psychologists, curriculum theorists and instructional researchers, and testing and assessment specialists” (Anderson, & Krathwohl, 2001, p. xxviii).

Like the original group, they were also arduous and diligent in their pursuit of learning, spending six years to finalize their work. Published in 2001, the revision includes several seemingly minor yet actually quite significant changes. Several excellent sources are available which detail the revisions and reasons for the changes. A more concise summary appears here. The changes occur in three broad categories: terminology, structure, and emphasis.

Terminology changes

Changes in terminology between the two versions are perhaps the most obvious differences and can also cause the most confusion. Basically, Bloom’s six major categories were changed from noun to verb forms. Additionally, the lowest level of the original, knowledge was renamed and became remembering. Finally, comprehension and synthesis were retitled to understanding and creating. In an effort to minimize the confusion, comparison images appear below.

Exhibit 4: Terminology changes “The graphic is a representation of the NEW verbiage associated with the long familiar Bloom’s Taxonomy. Note the change from Nouns to Verbs [e.g., Application to Applying] to describe the different levels of the taxonomy. Note that the top two levels are essentially exchanged from the Old to the New version.” (Schultz, 2005) (Evaluation moved from the top to Evaluating in the second from the top, Synthesis moved from second on top to the top as Creating.)

Source: http://www.odu.edu/educ/roverbau/Bloom/blooms_taxonomy.htm

The new terms are defined as:

- Remembering: Retrieving, recognizing, and recalling relevant knowledge from long-term memory.

- Understanding: Constructing meaning from oral, written, and graphic messages through interpreting, exemplifying, classifying, summarizing, inferring, comparing, and explaining.

- Applying: Carrying out or using a procedure through executing, or implementing.

- Analyzing: Breaking material into constituent parts, determining how the parts relate to one another and to an overall structure or purpose through differentiating, organizing, and attributing.

- Evaluating: Making judgments based on criteria and standards through checking and critiquing.

- Creating: Putting elements together to form a coherent or functional whole; reorganizing elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning, or producing.

(Anderson & Krathwohl, 2001, pp. 67-68)

Structural changes

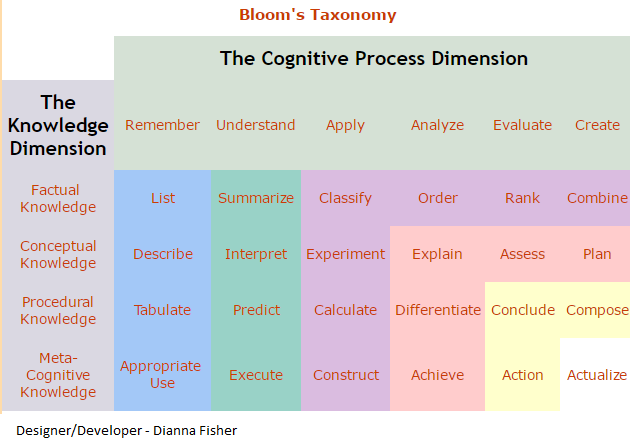

Structural changes seem dramatic at first, yet are quite logical when closely examined. Bloom’s original cognitive taxonomy was a one-dimensional form. With the addition of products, the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy takes the form of a two-dimensional table.

One of the dimensions, identifies The Knowledge Dimension (or the kind of knowledge to be learned) while the second identifies The Cognitive Process Dimension (or the process used to learn).

Each of the four Knowledge Dimension levels is subdivided into either three or four categories (e.g. Factual is divided into Factual, Knowledge of Terminology, and Knowledge of Specific Details and Elements). The Cognitive Process Dimension levels are also subdivided with the number of sectors in each level ranging from a low of three to a high of eight categories. For example, Remember is subdivided into the three categories of Remember, Recognizing, and Recalling while the Understanding level is divided into eight separate categories.

The resulting grid, containing 19 subcategories is most helpful to teachers in both writing objectives and aligning standards with curricular. The “Why” and “How” sections of this chapter further discuss use of the Taxonomy Table as well as provide specific examples of applications.

Table 1. Bloom’s Taxonomy

Copyright (c) 2005 Extended Campus — Oregon State University

Go to this following website and click on the verbs and see examples of learning objectives

http://oregonstate.edu/instruct/coursedev/models/id/taxonomy/#table

Changes in emphasis

Emphasis is the third and final category of changes. As noted earlier, Bloom himself recognized that the taxonomy was being “unexpectedly” used by countless groups never considered an audience for the original publication. The revised version of the taxonomy is intended for a much broader audience. Emphasis is placed upon its use as a “more authentic tool for curriculum planning, instructional delivery and assessment” (oz-TeacherNet, 2001).

Why use Bloom’s Taxonomy?

As history has shown, this well known, widely applied scheme filled a void and provided educators with one of the first systematic classifications of the processes of thinking and learning. The cumulative hierarchical framework consisting of six categories, each requiring achievement of the prior skill or ability before the next, more complex, one, remains easy to understand. Out of necessity, teachers must measure their students’ ability. Accurately doing so requires a classification of levels of intellectual behavior important in learning. Bloom’s Taxonomy provided the measurement tool for thinking.

With the dramatic changes in society over the last five decades, the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy provides an even more powerful tool to fit today’s teachers’ needs. The structure of the Revised Taxonomy Table matrix “provides a clear, concise visual representation” (Krathwohl, 2002) of the alignment between standards and educational goals, objectives, products, and activities.

- Today’s teachers must make tough decisions about how to spend their classroom time. Clear alignment of educational objectives with local, state, and national standards is a necessity.

Like pieces of a huge puzzle, everything must fit properly. The Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy Table clarifies the fit of each lesson plan’s purpose, “essential question,” goal or objective. The twenty-four-cell grid from Oregon State University that is shown above along with the printable taxonomy table examples can easily be used in conjunction with a chart. When used in this manner the “Essential Question” or the lesson objective becomes clearly defined.

How can Bloom’s Taxonomy be used?

A search of the World Wide Web will yield clear evidence that Bloom’s Taxonomy has been applied to a variety of situations. Current results include a broad spectrum of applications represented by articles and websites describing everything from corrosion training to medical preparation. In almost all circumstances when an instructor desires to move a group of students through a learning process utilizing an organized framework, Bloom’s Taxonomy can prove helpful. Yet the educational setting (K-graduate) remains the most often used application. A brief explanation of one example is described below.

The educational journal Theory into Practice published an entire issue on the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy.

Included is an article entitled, “Using the Revised Taxonomy to Plan and Deliver Team-Taught, Integrated, Thematic Units” (Ferguson, 2002).

The writer describes the use of the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy to plan and deliver an integrated English and history course entitled “Western Culture.” The taxonomy provided the team-teachers with a common language with which to translate and discuss state standards from two different subject areas. Moreover, it helped them to understand how their subjects overlapped and how they could develop conceptual and procedural knowledge concurrently. Furthermore, the taxonomy table in the revised taxonomy provided the history and English teachers with a new outlook on assessment and enabled them to create assignments and projects that required students to operate at more complex levels of thinking (Abstract, Ferguson, 2002).

Bloom’s group initially met hoping to reduce the duplication of effort by faculty at various universities. In the beginning, the scope of their purpose was limited to facilitating the exchange of test items measuring the same educational objectives. Intending the Taxonomy “as a method of classifying educational objectives, educational experiences, learning processes, and evaluation questions and problems” (Paul, 1985 p. 39), numerous examples of test items (mostly multiple choice) were included. This led to a natural linkage of specific verbs and products with each level of the taxonomy. Thus, when designing effective lesson plans, teachers often look to Bloom’s Taxonomy for guidance.

Likewise the Revised Taxonomy includes specific verb and product linkage with each of the levels of the Cognitive Process Dimension. However, due to its 19 subcategories and two-dimensional organization, there is more clarity and less confusion about the fit of a specific verb or product to a given level. Thus the Revised Taxonomy offers teachers an even more powerful tool to help design their lesson plans.

As touched upon earlier, through the years, Bloom’s Taxonomy has given rise to educational concepts, including terms such as high and low level thinking. It has also been closely linked with multiple intelligences (Noble, 2004) problem solving skills, creative and critical thinking, and more recently, technology integration.

Using the Revised Taxonomy in an adaptation from the Omaha Public Schools Teacher’s Corner, a lesson objective based upon the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears is presented for each of the six levels of the Cognitive Process as shown on the Revised Taxonomy Table.

- Remember: Describe where Goldilocks lived.

- Understand: Summarize what the Goldilocks story was about.

- Apply: Construct a theory as to why Goldilocks went into the house.

- Analyze: Differentiate between how Goldilocks reacted and how you would react in each story event.

- Evaluate: Assess whether or not you think this really happened to Goldilocks.

- Create: Compose a song, skit, poem, or rap to convey the Goldilocks story in a new form.

Although this is a very simple example of the application of Bloom’s taxonomy the author is hopeful that it will demonstrate both the ease and the usefulness of the Revised Taxonomy Table.

Conclusion

Countless people know, love and are comfortable with the original Bloom’s Taxonomy and are understandably hesitant to change. After all, change is difficult for most people. The original Bloom’s Taxonomy was and is a superb tool for educators. Yet, even “the original group always considered the [Taxonomy] framework a work in progress, neither finished nor final” (Anderson & Krathwohl 2001 p. xxvii). The new century has brought us the Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy which really is new and improved.

Media

Watch this video from ITC Publications: “Bloom’s Taxonomy of the Cognitive Domain Explained”

[ITCPublications]. (2013, Dec. 3). Bloom’s Taxonomy of Cognitive Domain Explained. [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/g1lc-GWtGII

https://youtu.be/g1lc-GWtGII

Extended Campus- Oregon State University has an interactive Bloom’s Taxonomy chart of the six Cognitive Process dimensions (Remember, Understand, Apply, Analyze, Evaluate, and Create) with the four Knowledge Dimensions (defined as Factual, Conceptual, Procedural, and Meta-Cognitive) forming a grid with twenty-four separate cells as represented.

Each of the cells contains a hyperlinked verb that launches a pop-up window containing definitions and examples. Check it out and use these types of verbs in your lesson objectives. Use this table in conjunction with Printable Taxonomy Table Examples to clearly define the “Essential Question” or lesson objectives.

Online resources on Bloom’s Taxonomy

Keep these resources on hand as a guide when you are writing lesson plans, developing learning objectives, student tasks, questions, and assessments.

Sample Question Stems Based on Revised Bloom’s Taxonomy

Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy: Mathematics

Kathy Schrock has organized apps across the six levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy-“Bloomin Apps”

References

Forehand, M. . (2010) Emerging Perspectives on Learning, Teaching, and Technology, Global Text, Michael Orey. (Chapter 3). Retrieved from https://textbookequity.org/Textbooks/Orey_Emergin_Perspectives_Learning.pdf