1.4 Basic Concepts

Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN)

When performing a general survey assessment, nurses use all of their senses to carefully observe the patient. They look at a patient and ask themselves, what are they seeing? They listen to a patient and ask themselves, what are they hearing, both verbally and nonverbally? They smell a patient’s odors and ask themselves, is there anything unusual we need to further assess? They observe a patient’s behaviors and make notes about their functioning and ability to complete daily activities according to their developmental level.

Before performing a general survey assessment, it is important to first ensure the patient is medically stable by completing a brief primary survey. After ensuring the patient is medically stable, a general survey assessment is an overall observation of a patient’s general appearance, behavior, mobility, communication, nutritional, and fluid status. A general survey assessment also includes analyzing height, weight, and vital signs for values that are out of range and require additional follow-up.

Primary Survey

At the beginning of every shift or patient visit, nurses perform a brief primary survey to ensure their patient is medically stable. If any signs indicate patient distress, the provider is notified and emergency care is initiated. For example, changes in level of consciousness or abnormal vital signs often provide early warning signs that a patient’s condition is deteriorating and prompt medical treatment is needed.[1] Mental status, airway, breathing, and circulation are also quickly assessed and emergency actions taken as needed.[2]

In a clinic setting, the patient is observed from the time they are called from the waiting room. Nurses observe a patient’s gait and balance as they walk to the exam room and assess their verbal and nonverbal communication while interacting. If signs of distress are occurring, the nurse follows agency policy and either immediately calls a provider into the room or initiates emergency assistance.

Mental Status

When assessing a patient’s overall mental status, it is important to compare findings to their known baseline if this information is known or available. Initially determine if a patient is responsive or unresponsive. Can you awaken them and are they responding to your questions? Are they oriented to person, place, and time, meaning can they tell you their name, location, and the day of the week? If you are concerned about a sudden change in a patient’s mental status, obtain emergency assistance according to agency policy.

Airway and Breathing

Determine if the patient’s airway is open and if they are breathing adequately. Institute emergency care for respiratory distress as needed. See Figure 1.20[3] for an illustration of checking a patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs).

Circulation

If a patient is not responsive, try to awaken them using a sternal rub. A sternal rub is performed by firmly rubbing one’s knuckles on a patient’s sternum to try to elicit a response. If they do not respond, check the carotid pulse and obtain emergency assistance as needed. Briefly observe the color and moisture of their skin. Abnormal findings such as cool, moist, pale, or bluish skin can indicate signs of shock that require emergency care.

General Appearance

After ensuring your patient is medically stable by completing a primary survey, a general survey consists of using your senses to observe a patient’s general appearance, behavior, mobility, and communication. Items to consider when assessing general appearance include the following:

- Signs of pain or distress: Patients may exhibit signs of pain or distress that should be reported to the provider such as grimacing, moaning, or increased anxiety. Set the priorities for your focused assessments based on any signs of distress demonstrated by your patient.

- Age: Observe if the patient appears their stated age. Chronic disease can cause a patient to appear older than their age. Factors can occur with older adults that may influence how well the patient can participate in the assessment, such as hearing, vision, or mobility impairments.

- Body type: No patient is exactly the same; some patients are in good physical shape and others are not. Body type can reflect nutritional status and lifestyle choices.

- Hygiene, grooming, and dress: Observe the overall cleanliness of the patient’s hair, face, and nails and note any odors. Odors can indicate poor hygiene or various disease states. Validate odors by performing additional focused assessments as needed. Note the appearance of the patient’s clothing; is it clean and appropriate for the season? If not, findings can reflect on a patient’s cognitive abilities, emotional state, and ability to complete daily activities.

Behavior

While observing the patient, note their behaviors during your interaction. Consider the following items:

- Affect and mood: People express their mood through facial expressions, eye contact, what they do, and what they say. Eye contact is commonly used to judge a person’s mood because people who are feeling down or depressed commonly avoid eye contact. However, be aware that cultural beliefs may also affect the use of eye contact. Affect refers to the outward display of one’s emotional state. For example, a patient with a “flat affect” refers to very few facial expressions being displayed to indicate emotion, which is often associated with depression. If the patient’s mood or behavior seems inappropriate for their current situation, make a note of that as well. For example, a patient in an usually elated mood in a situation when most people would be seriously concerned can be a symptom of mental illness.

- Family dynamics: If other family members are accompanying the patient, note the characteristics of their interactions. Family dynamics are the patterns of interactions between family members that influence family structure, hierarchy, roles, values, and behaviors. Family dynamics have a strong impact on the way children see themselves, others, and their world. They can also impact the lifestyles of older adults who rely on their children for assistance in activities of daily living and health care.

- Signs of patient abuse: Abuse occurs in many different forms such as physical, emotional, mental, verbal, sexual, economic, or financial. Most states mandate nurses and other health care professionals to report suspected child and elder abuse to the proper authorities. Observe if your patient seems fearful, excessively quiet, or has physical signs of abuse, such as bruising or burn marks. If you suspect abuse, attempt to interview the patient alone. Promptly report your concerns according to agency policy and state mandates.

- Substance use disorder: Approach your patient in a caring and nonjudgmental way, but be aware that unusual signs or behaviors can be indicators of substance use disorder. For example, if a patient’s pupils are unusually dilated or constricted, this can be a sign of substance use disorder. Contact the provider with concerns about substance use disorder.

See Figure 1.21[4] of an image of a man with poor hygiene and nonverbal behavior requiring further assessment, such as disease management, medication management, and ability to complete activities of daily living.

Mobility

Observe your patient’s body movements, noting posture, gait, and range of motion.

- Posture: Patients with normal sitting and standing posture are upright and have a parallel alignment from the shoulders to the hips. Note if the patient is hunched, slumped, contracted, or rigid. See Figure 1.22[5] for an image of a patient with a type of slumped posture called kyphosis.

-

- Gait and balance: Observe how the patient walks or stands. Are the movements organized, coordinated, or uncoordinated? Are they able to maintain balance while standing without leaning on or touching anything? Healthy people walk with a smooth gait and arms moving freely at their sides and are able to stand unassisted. A change in gait or balance often signifies underlying health conditions and increases the risk of falling. See Figure 1.23[6] of a patient learning how to use an assistive device for an altered gait.

Figure 1.23 Altered Gait with Assistive Device

- Gait and balance: Observe how the patient walks or stands. Are the movements organized, coordinated, or uncoordinated? Are they able to maintain balance while standing without leaning on or touching anything? Healthy people walk with a smooth gait and arms moving freely at their sides and are able to stand unassisted. A change in gait or balance often signifies underlying health conditions and increases the risk of falling. See Figure 1.23[6] of a patient learning how to use an assistive device for an altered gait.

Range of motion and mobility: Observe the patient moving their extremities. Do extremities on the right and left sides move equally? Note any tremors or movements that are not purposeful. Are the patient’s abilities appropriate for their age? Is the patient moving normally or do they have specific limitations? Does the patient use any assistive devices such as a cane or walker? Mobility is an important component in being able to care for oneself independently, so note any potential concerns for adults that may impact their ability to complete activities of daily living.

Communication

- Speech: Observe how your patient is speaking during your interaction. Are they speaking in an understandable tone and even pace, or is it garbled or difficult to understand? Neurological disorders can cause speech to be slow, slurred, and hard to understand. Is there an emotional component to their words? Is there a language barrier requiring an interpreter?

- Response to commands: Does the patient follow instructions you are providing during your assessment, or do they have difficulty in understanding or cooperating?

Nutritional Status

Visually observing the patient’s overall nutritional status can provide cues for additional focused assessments related to appetite, diet, food intake, or exercise. Many factors can influence a patient’s nutritional status such as financial or transportation issues, swallowing difficulties, missing teeth, or poorly fitting dentures.

Fluid Status

Observe overall fluid status. Dehydration can be indicated by dry skin, dry mucous membranes, or sunken eyes. Conversely, patients with excess fluid often have swelling or edema in their extremities and may exhibit signs of difficulty breathing.

Height, Weight, and BMI

Height and weight can be used as a guide to reflect the patient’s general health. Weight is routinely assessed during all health care visits. Infants and children are measured to assess their growth and development. Hospitalized patients often have daily weights assessed to monitor for changes in their medical condition. Document findings based on agency policy. For example, in some agencies, height is documented in centimeters and weight is documented in kilograms. Recall that one inch is equivalent to 2.5 centimeters and 1 kilogram is equivalent to 2.2 pounds.

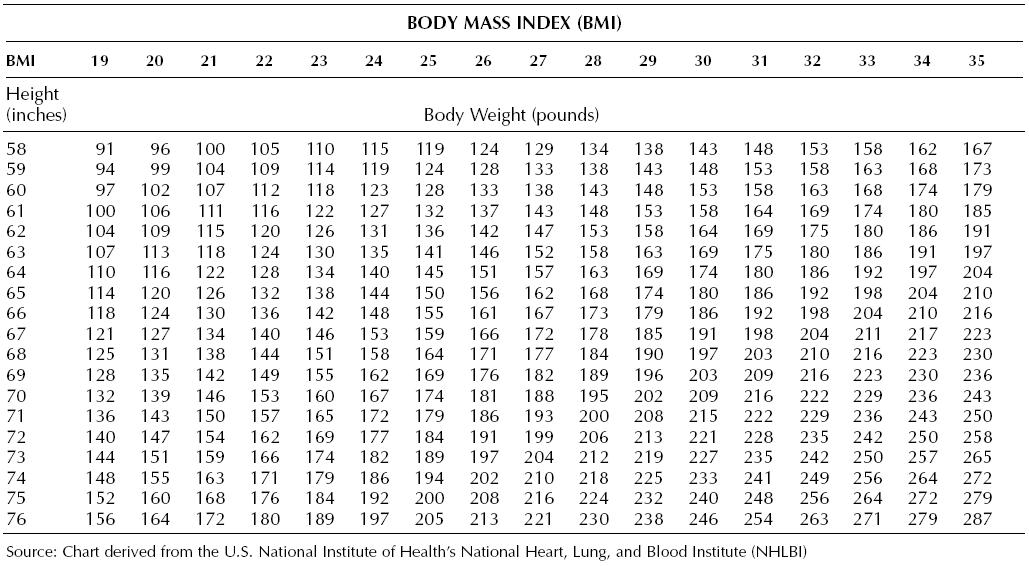

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a standardized reference range that is used to analyze a patient’s weight status and provides a representation of body fat. However, it is important to note that BMI may not be accurate for athletes with increased muscle mass, people with edema or dehydration, or older adults who have lost a significant amount of muscle mass. See a BMI table in Figure 1.24.[7] To use the BMI table, find the height in inches in the left column, move across the row to closest weight, and then read the BMI where the column and row intersect. For example, a person who is 5′ 9″ tall is 69 inches. If the patient weighs 155 pounds, the BMI is 23. BMI indicating a healthy weight is between 18.5 to 24.9.

BMI can also be calculated using the formula of BMI = kg/m2 (weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared).

The following classifications are used based on a person’s BMI:

Underweight: Below 18.5 kg/m2

Healthy weight: 18.6 to 24.9 kg/m2

Overweight: 25 to 29.9 kg/m2

Obesity: Over 30 kg/m2 to 34.9 kg/m2

Extreme obesity: Over 35 kg/m2

Life Span Considerations During a General Survey Assessment

Children

When performing a general survey on a child, be aware of their developmental stages to establish expectations for normal findings. Use a calm and gentle tone to establish trust. Demonstrations on dolls or stuffed animals before performing procedures are often helpful. Be aware that the parents of toddlers and school-aged children will likely provide most of the information during an assessment.

Adolescents

Adolescents may refrain from sharing important information related to their care in front of their parents, especially regarding high-risk behaviors such as smoking, alcohol or drug use, sexual activity, or suicidal thoughts. It is often helpful to allow time to interview the adolescent privately, in addition to gathering information when the parent is present.

Older Adults

Recognize normal changes associated with aging when performing a general survey. If your patient wears glasses or hearing aids, be sure they are in place before asking questions. You may need to allow for extra time for your assessment, depending on the abilities of your patient. If an older adult is unable to communicate effectively, nurses may also consult a variety of sources such as family members and electronic medical records for more information.

Cultural Adaptations During a General Survey Assessment

Adapt your communication during a general survey assessment to your patient’s cultural beliefs and values. For example, some individuals believe that direct eye contact with authorities is considered disrespectful and avoid eye contact. Other individuals may nod to indicate they are listening but this does not mean they are in agreement with what you are saying. Some patients prefer that a same sex individual perform care. For additional details about caring for diverse patients, see the “Diverse Patients” chapter in the Open RN Nursing Fundamentals textbook.

- This work is a derivative of StatPearls by Toney-Butler and Unison-Pace licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Chemical Hazards Emergency Medical Management. (2020, April 17). Primary and secondary survey. National Institutes of Health. https://chemm.nlm.nih.gov/appendix8.htm ↵

- “Checking respiratory.png” by User:Rama licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 FR ↵

- “Homeless man in Los Angeles(7618018076).jpg” by Alex Proimos licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- “Posturalkyphosis” by Lab Science Career licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 ↵

- “US_Navy_071015-N-5086M-202_Retired_Marine_Corps_Cpl._Timothy_Jeffers_walks_on_his_prosthetic_legs_while_using_the_hands-free_harness_walking_gait_training_device_during_a_therapy_session_in_the_new_Comprehensive_Combat_and_Com.jpg” by U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Greg Mitchell is in the Public Domain ↵

- This work is a derivative of U.S. National Institutes of Health’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), https://www.wikidoc.org/index.php/File:BMIReferenceChart.jpg licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

A brief observation at the start of a shift or visit to verify the patient is stable by assessing mental status, airway, breathing, and circulation.

Outward display of one’s emotional state. A “flat” affect with little display of emotion is associated with depression.

Patterns of interactions between family members that influence family structure, hierarchy, roles, values, and behaviors.

A standardized reference range to gauge a patient’s weight status.