10

Stephen Posner

The world needs scientists to discover new knowledge and deepen society’s understanding of grand sustainability challenges. Now, more than ever, society also needs scientists to connect knowledge to action, evaluate solutions, and contribute to sound policy. The ability of society to navigate sustainability challenges depends more on the application and use of scientific evidence than on the accumulation and publication of research (Evans & Cvitanovic, 2018; Sutherland, Pullin, Dolman, & Knight, 2004). Fortunately, today, many scientists are eager to do research that impacts policy. However, there remains a sizeable gap between wanting to impact policy and having the knowledge, skills, and support to effectively engage with policymakers and policy processes.

Below are two short stories that demonstrate how early career scientists can become sustainability leaders who meaningfully impact policy. In 2015, Kathy Zeller was an environmental conservation Ph.D. student at the University of Massachusetts. She attended a policy workshop through her Switzer Fellowship and learned about a potential federal bill to support wildlife corridors. She saw policy relevance in her own research, worked with professionals at the non-profit COMPASS to connect her research with policy conversations, and contributed to an effort to establish a national system of wildlife corridors. Kathy engaged in dialogue with federal policy staff about her science and the proposed bill. In meetings with the office staff of a congressman, Kathy delivered compelling science messages that linked her research with what the policymaker cared about by describing how wildlife corridors are good for biodiversity as well as agricultural productivity and recreational industries. While the ultimate outcome of the proposed legislation is uncertain, Kathy’s efforts shed light on the need to protect broader, interconnected areas of public land rather than only isolated patches.

In the same year, Aerin Jacob was a postdoctoral fellow in geography and environmental studies at the University of Victoria and the Wilburforce Fellowship in Conservation Science. As part of her fellowship, Aerin attended a workshop and set a goal to do something about the lack of attention being paid to science in an upcoming national election in Canada. Aerin planned an all-candidates’ debate and worked with the host of a popular Canadian science radio program to be a guest moderator. Three leading political candidates participated in a unique public discussion that gave science and technology a prominent role in policy. The debate received positive news coverage and included remote listeners and participants from around the world. One year later, Aerin led a national effort that engaged over 1,900 early career researchers and encouraged them to address the government’s environmental assessment law, policy, and practices.

Aerin’s initiative encouraged policymakers to recognize the value of science in public policy and also influenced her fellow citizens’ thinking about science, society, and the environment during an election. Kathy’s awareness of her research’s policy implications and her ability to effectively communicate with policy staff transformed a federal policy dialogue to include broader, more impactful solutions. Yet, neither of them woke up one day and knew how to engage with policy processes. They received training and support in key aspects of connecting science and policy. They took time to develop goals, a sense of whom to engage, and effective action plans.

This chapter focuses on what it takes for emerging leaders to engage with the policy world and impact policy. In doing so, the importance of training, support, and connections between being a good communicator and being a sustainability leader who transforms public dialogue are emphasized. The ideas in this chapter draw from applied work that connects science and policy as well as diverse theoretical perspectives on science communication and the science-policy interface.

This chapter was written with a particular audience in mind: university faculty and staff who support early career scientists and emerging sustainability leaders. A related audience includes leaders themselves. The main goals for these groups are to 1) see policy engagement as an important way for academic scientists to address complex sustainability challenges and 2) understand key factors for successful policy engagement. The aim of the chapter is to encourage graduate students, faculty, and staff to change academic systems and institutional cultures to better support scientists in connecting their research with policy.

While emerging sustainability leaders can play key roles in linking knowledge with action when they take opportunities to engage and receive effective training and support, the incentive systems for higher education professionals do not always align with policy engagement. Thus, cultivating the next generation of sustainability leaders involves developing the capacity of programs to adapt and meet societal needs. Institutions and programs that support emerging leaders’ engagement with policies can become more relevant and integrated with their surrounding social contexts (Cvitanovic, Lof, Norstrom, & Reed, 2018; Posner & Stuart, 2013). Strengthening connections between research and policy will inspire the creation of science that is more relevant to decision making and more responsive to complex societal challenges.

What Is Policy Engagement and Why Is Supporting Emerging Leaders’ Engagement Important?

What does policy engagement mean? Any institution or program that supports emerging leaders’ engagement would benefit from defining key terms and building a common vocabulary. This chapter uses the following terms in the following manner:

- Policy means the “sum total of government action, from signals of intent to the final outcomes” (following Cairney, 2016, p. 19).

- Engage means to participate and interact in a deliberate, meaningful way that opens and advances dialogue and facilitates mutual learning between scientists and policy actors.

- Pathway describes an opportunity for scientists to engage.

- In combination, a policy engagement pathway refers to an approach or opportunity available to scientists who aim to impact policy.

- The term ‘policymaker’ is used in a general sense to refer to the official, elected policymakers, as well as other actors who ‘make policy happen.’ This includes policy staff, such as schedulers and legislative assistants, and others who influence policymakers, such as directors and senior advisors.

In general, an important quality of a sustainability leader is the ability to connect with diverse audiences beyond their peers. Leaders who are more advanced in their careers often have well-developed networks. Emerging leaders may have an appetite for broader impact, but often need support to skillfully navigate subtle aspects of the policy world. Such support could have an enduring, positive influence in the early stage of their professional careers.

Policy engagement can fundamentally affect how emerging leaders view and conduct their science. When scientists develop the ability to interact with policymakers in meaningful ways, they learn to create a more inclusive, iterative knowledge exchange (Bednarek et al., 2018). Creating more dynamic relationships between scientists and policymakers throughout the research process can foster opportunities for scientific evidence to be useful in decision making (Alberts, Gold, Martin, & Maxon, 2018; American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), 2017; Posner, McKenzie, & Ricketts, 2016). Scientists can benefit from engaging with policymakers by being informed about the very research questions they ask. Ultimately, policy engagement can lead to scientists and policymakers co-producing knowledge and research and further alignment of the knowledge that scientists produce and the knowledge that policymakers need (Smith et al., 2013).

Emerging leaders may have concerns about engaging with policy, such as how policy-related activities could affect their scientific objectivity. As described later in this chapter, there are many different roles for scientists to play in policy processes. Some roles involve advocating for particular solutions while others hinge on remaining more neutral. With support and guidance, individuals can thoughtfully define a role for themselves that aligns with their own personal interests, beliefs, and comfort.

Other legitimate concerns include whether engaging with policies would distract from scientific career progress or cause tension with supervisors or colleagues who have different views on policy engagement. However, many scientists agree that people with a strong science perspective are important contributors to solving societal challenges. In addition, engaging with the public sphere can improve scientific skills such as explaining complex ideas or analyzing data to answer a specific question. Policy engagement can also unlock exciting career opportunities beyond academia. For emerging leaders, a discussion with colleagues about broader impacts and the difference they would like to make in the world could demonstrate how policy engagement contributes to professional and personal goals.

While there is no guarantee that engaging with policymakers will result in better or more informed policy decisions, it could be the difference between science being part of a decision or being left out of consideration (Rowe & Lee, 2012). Cultivating the next generation of sustainability leaders to link knowledge to action is critical for the inclusion of sound science in decision making.

Planning for Policy Impact

It is not always clear to emerging leaders how to effectively work across the professional, cultural, and institutional boundaries between academia and the policy world (Bernstein, Reifschneider, Bennett, & Wetmore, 2017). Engaging with policy processes often means navigating new and unfamiliar terrain. Emerging leaders would benefit from a supportive framework for policy engagement.

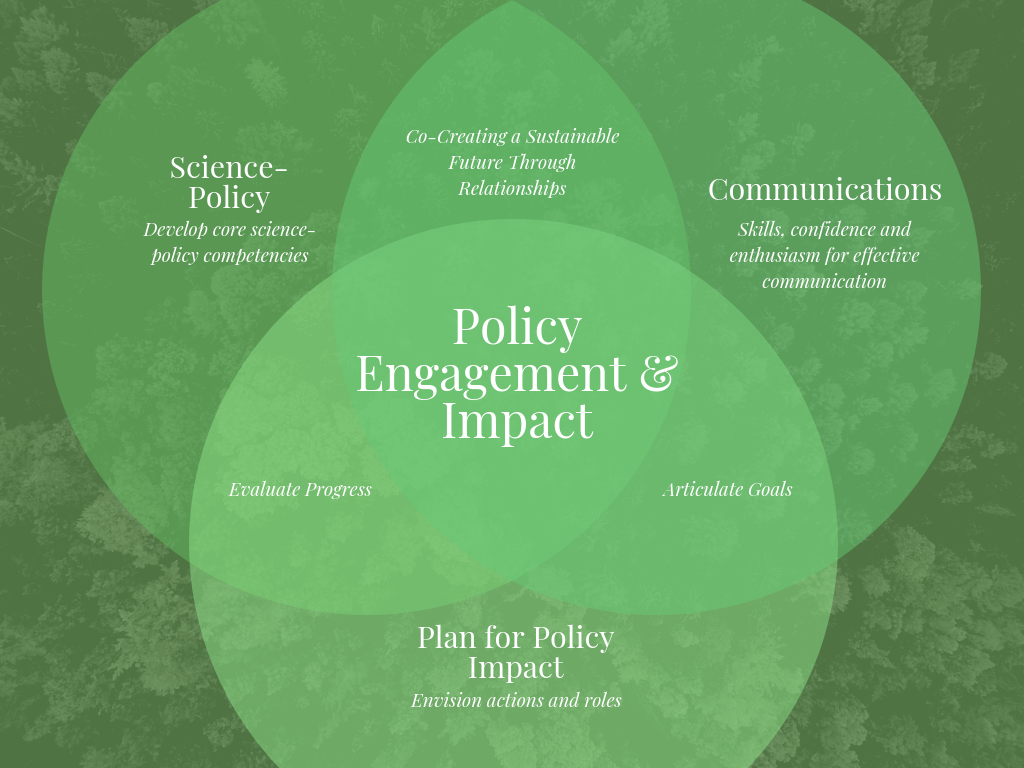

A framework for institutions that value broader impacts would support emerging leaders in 1) articulating their policy goals, 2) evaluating progress toward their goals, and 3) envisioning specific actions they could take and roles they could play. In this section, these components are described in more detail. In the following sections, the importance of institutions and programs providing opportunities for emerging leaders to develop the civic competencies and communication skills that are essential to effectively engaging in policy conversation is also emphasized.

Articulating policy engagement goals lays the groundwork for success. As Aerin from the beginning of this chapter put it: “I set a goal to get Canadian political candidates to publicly discuss science, which metamorphosed into Canada’s first all-candidates’ debate on science.” Her goal of having political candidates publicly discuss science was ambitious, yet doable. Achieving her goal provided something important that the world needed: a more public debate about the role of science in society. A key dimension of the Wilburforce Fellowship that Aerin received was supporting emerging leaders in articulating and refining their goals. Unfortunately, some academic programs do not support emerging leaders in aiming for ambitious goals that have a broader impact, in part because they deem broader impacts as tangential to, or distracting from, academic research. Programs’ lack of support for setting policy impact goals leads to missed opportunities for institutions and scientists to affirm their relevance to society. A co-production model of science, whereby scientists and policymakers (or other stakeholders) jointly define goals, research questions, methods, and actionable outputs is one promising way to link research knowledge with action (Beier, Hansen, Helbrecht, & Behar, 2017).

The second component of planning for policy impact, measuring progress toward goals, is essential but often overlooked. Supporting emerging leaders in identifying indicators of successful policy engagement and evaluating their efforts helps leaders sharpen their thinking about goals. Evaluating progress requires leaders to be specific and strategic about their objectives and facilitates continuous learning (Posner & Cvitanovic, in review). Programs can provide guidance that aligns measures of individual progress with measures of institutional or program-level success.

The third component, envisioning actions and roles, is an exciting aspect of implementing policy engagement plans that deserves special attention. In the case of Aerin, she noticed a window of opportunity in an upcoming election cycle and strategically thought about pathways to accomplishing her goal. Her willingness to engage motivated her to have conversations with key people, who in turn, helped her to come up with the idea of holding a debate. She put together a team of like-minded individuals that helped do the work necessary to see the vision through. She drew support from different sources, including peer relationships that were strengthened in workshops provided by her fellowship.

In many cases, the actions of an emerging leader will define their role in a policy system. A scientist who organizes a group of people to raise awareness of an issue (such as public debate about science) serves in a convener role. A scientist who shares research findings that suggest new solutions can fill a role as a technical expert. A technical expert can also help policymakers navigate the scope of expertise that exists for an issue and point out others with relevant expertise. A scientist who analyzes possible solutions or describes what would likely occur if a particular solution were implemented plays an important evaluator role. In these ways, scientists can empower decision makers by clarifying choices, accessing expertise, and framing the scope of possible solutions.

A scientist who promotes a particular policy solution or encourages a decision maker to take a specific course of action assumes the role of advocate. Advocacy can be impactful, and the degree to which one advocates for a particular solution is a personal choice. It is important for scientists to be aware of the risks (e.g., risks to one’s reputation as a more neutral stakeholder), rewards (e.g., a goal might be to sway policy outcomes), and constraints (e.g., university rules about lobbying) involved in advocacy or efforts to directly influence decision-making outcomes.

Much has been written about the roles of scientists in policy processes (Baron, 2016; Cairney, 2016; Pielke, 2003). Some feel that scientists should contribute policy-neutral information and avoid advocating personal positions (Lackey, 2006). Emerging leaders benefit from reflecting on how they would like to show up. Programmatic support that provides opportunities for self-reflection through facilitated group discussion, writing prompts, or individual advising can help leaders appreciate their own growth and evolution as they plan for impact and engage with public issues. After organizing the public debate, Aerin reflected on how, “More broadly, I see my contributions now more as part of long-term processes and less as one-off events.”

Self-reflection can also help emerging leaders understand how their personal preferences, values, and strengths shape whether they are a good fit for any given opportunity. While planning for policy impact, reflective processes can also help leaders overcome barriers that may limit access to opportunities. For example, an engagement pathway may be more or less accessible depending on career stage (i.e., early career, mid-level, senior) or individual or social characteristics (i.e., gender, race, or other forms of diversity). Supportive institutional cultures based on inclusion and representation of diverse populations enrich the scientific enterprise and make it easier for individuals to navigate social barriers to policy engagement (Puritty et al., 2017).

Core Competencies

A framework that supports sustainability leaders in articulating goals, evaluating progress, and envisioning actions and roles is a useful start but is incomplete. To deliberately impact policy, an emerging leader needs to understand key aspects of government, policy, and politics. Scientists who know how policy is made can identify opportunities for change and effectively engage with influencers, partners, and decision makers. The following suggested topics help graduate students, faculty, and staff develop the core competencies necessary to successfully engage.

Civics 101

Leaders who understand the fundamentals of government and how it works at different levels (e.g., federal, state, county, municipal) are more prepared to impact policy, navigate policy systems, and work in whatever levels are most appropriate for their goals. Each country has its own government structure that has a significant bearing on how a government functions. For example, in the U.S., at the federal level, it is important to be familiar with the three branches of government (executive, legislative, and judicial), what happens within each branch, and how the different branches interact. These insights allow a leader to navigate the system to find levers of change. An institution or program can train emerging leaders to be able to make sense of the networks, hierarchies, and “rules of the system.” Understanding authority and jurisdiction in terms of who can do what, in which order, and why, empowers emerging leaders to effect change. It is important to note that there are also many pathways to impacting policy that are beyond government. These involve working with non-governmental organizations, civil society groups, and others to engage with policy processes.

The Role of Scientific Evidence in Policy

Policy processes are complex and messy. Scientific evidence is just one of many different types of information that policymakers acquire, scrutinize, debate, and use (or not) as a basis for decisions. Emerging leaders who appreciate how and why policymakers use scientific evidence will be less surprised by the realities of policymaking and more skillful in how they engage (Akerloff, 2018; Bipartisan Policy Center, 2018; Kenny, Rose, Hobbs, Tyler, & Blackstock, 2017). Generally speaking, policymakers often use scientific evidence to frame ideas and shape the way people see issues, build support for ideas or plans, and provide a basis for specific decisions or courses of action (McKenzie et al., 2014). Timing is a key determinant of the role that scientific evidence plays in policies. A policymaker may use scientific evidence differently throughout policy processes depending on whether people are identifying a problem, considering options for what to do about it, or implementing solutions.

The Role of Scientists in Policy

Earlier, the importance of individual leaders reflecting on the roles they can play in working towards a policy engagement goal was described. In this section, the general roles that scientists can play in policy processes are elaborated upon. A program that supports policy engagement makes it easier for emerging leaders to:

- Frame the dialogue and find out which questions policymakers are asking and seeking answers to;

- Define a problem and signal the need for action (for example, the distribution of a species is shifting, there are follow-on impacts to people, and current management tools are inadequate to address the situation);

- Raise awareness and expand the range of options for policymakers or managers to consider; and

- Clarify specific options that meet policy, management, and stakeholder needs as policy conversations shift to exploring solutions that can be implemented.

Again, timing can be a key factor. “Policy windows” are discrete windows of time that offer an opportunity to influence policy. Policy windows are frequently unpredictable, and scientists need to be able to act on short notice to take advantage of strategic opportunities to engage with decision makers. Institutions and programs can help emerging leaders respond to policy windows by foreseeing opportunities, supporting communication and framing that aligns with appropriate windows and creating new windows (Rose et al., 2017).

How Policymakers Perceive Scientists and Scientific Evidence

Science is most effective in shaping discourse and informing decisions when policymakers see it as credible (based on rigorous technical expertise), legitimate (fair, unbiased, and representative of different viewpoints), and salient (timely and relevant to the issues at hand; Cash et al., 2003; Posner, McKenzie, & Ricketts, 2016). The reputation and skill of a researcher contribute to the perceived credibility, legitimacy, and salience of the scientific evidence they produce. Personal relationships, apparent motivations, and other social and political factors also affect how a policymaker perceives scientists and scientific evidence. Effective policy engagement requires trust among science ‘producers’ and ‘users’ (Lacey, Howden, Cvitanovic, & Colvin, 2017). Institutions and programs can encourage emerging leaders to become trusted resources that policymakers turn to for information and analyses.

Long-term, Trusting Relationships

Sound, scientific evidence is necessary for policy impact but is insufficient by itself. Impact arises from people’s relationship with scientific evidence. Thus, it’s important for programs to support strategic thinking about whom to engage with and how. Beyond policymakers themselves, it is essential for scientists to build relationships with policy staff and entrepreneurs who track conversations and facilitate policymaking because these people can help navigate new networks, anticipate trajectories, and provide on-the-ground insights and guidance. Building relationships with people who make policy happen helps align research with policy needs, increase trust, and increase the likelihood of policymakers using sustainability research in their decision making. In this way, emerging leaders who engage with policy people can build a richer and more effective community of practice while working on complex sustainability issues.

Focus on Communication

An emerging sustainability leader will be well-equipped to make changes if they have a policy engagement plan and a solid understanding of core science-policy concepts. Adding communication skills, confidence and enthusiasm will significantly boost their capacity to impact policy. Thus, a central aspect of support for sustainability leaders is cultivating good communication.

Communication is not an add-on to science; it is central to the enterprise (Baron, 2010a; Smith et al., 2013). Effective communication enhances knowledge exchange between scientists and policymakers (Cvitanovic, McDonald, & Hobday, 2016). Honing communication skills improves an emerging leader’s ability to engage with diverse audiences, articulate a vision, and “talk about their science in ways that make people sit up, take notice, and care” (Baron, 2010b, p. 1032).

Institutions and programs play an important role in cultivating good communicators. They can provide opportunities for emerging leaders to practice and hone their ability to communicate sustainability-related research to audiences beyond academia. They can also facilitate productive dialogue among faculty, staff, and graduate students about which audiences are most important to engage. Better communication of sustainability topics across traditional disciplinary boundaries in academia (including between social and natural sciences) can increase the impact of research by making it more accessible to people of all backgrounds.

The following five practical guidelines can help sustainability leaders develop top-flight communication skills. These tips and insights draw from decades of organizations such as COMPASS studying, developing, and testing science communication approaches. While these guidelines are primarily based on communicating a message to an audience, it is important to emphasize the value of two-way communication. Simply providing information to policymakers in a “linear transaction” does not necessarily lead to it being used (Beier et al., 2016). Listening to policy audiences is vital for relationships that strengthen, expand, and diversify the networks of people that emerging leaders work with to advance sustainability and coproduce solutions.

Know the Audience. Understand what the audience cares about. What matters to the policymaker that is being engaged? What is most important to them? What do they value? What are they concerned or worried about? Who are their constituents?

Frame the Message. Align and connect the message with what the audience cares about (COMPASS Science Communication, Inc., 2017). For a policymaker, this could be their agenda, their policy priorities, or the interests of their constituents. Build common ground, get to the point, and make it clear why the audience should want to pay attention. Learn to effectively frame how research can advance a particular policy conversation.

Limit the Number of Ideas. People’s working memory stores a limited amount of information. Thus, any audience is likely to only remember a small number of key points that are made. Bombarding them with evidence or data can distract from the core message. Communication about complex sustainability topics is more impactful if the number of ideas focused on is limited to three to five key points.

Avoid Jargon and Distill Complexity. The message will be more impactful if the audience understands what is being said. This is especially true for written policy briefs that may only receive seconds of a policymaker’s time and attention (Balian et al., 2016). Communicate at the level of expertise of the other person. Make things easy to understand for the audience. Share ideas with language that is clear, jargon-free, and simple (but not simplistic).

Tell a Story. This story would preferably be one that features people who live at an address within the jurisdiction of the policymaker. Stories can define issues, provide evidence, and describe solutions in compelling ways (Cairney & Kwiatkowski, 2017). A well-crafted story can add rich layers of meaning to data and research. For example, a story can show how the spread of an invasive plant species impacts people in surprising ways and has implications for issues a policymaker might care about such as increasing tourism, growing food, or hunting and fishing. Stories can also cultivate trust and signal positive intentions by allowing the leader to share why they do what they do.

A Supportive Framework for Policy Engagement

The emerging leaders featured at the beginning of this chapter received key support that helped them develop clear policy engagement plans, science-policy know-how, and effective communication. Institutions and programs that provide such support will foster sustainability leaders who are well-equipped to create change. Leaders can be successful in policy engagement without having a supportive framework, but they are more likely to realize broader impacts on the world if institutions provide scaffolding for policy engagement planning, science-policy proficiency, and strong science communication.

Institutions can provide practical leadership development opportunities by partnering with organizations that specialize in this field such as COMPASS, The Alda Center for Communicating Science, The American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS), and professional societies. These groups provide hands-on communication and policy workshops that enable scientists to learn new approaches and hone their skills. Such experiences can provide peer support and mentorship opportunities with other leaders outside the typical academic system. Organizations such as COMPASS also work on the ground to span boundaries between science and decision making and facilitate knowledge exchange (Bednarek et al., 2018). In addition to partnerships with external organizations, many universities have robust legislative affairs offices or institutes that can provide opportunities for policy engagement at the local, state, and federal levels.

Programs that build a framework (see Figure 1) for early career scientists to engage with policymakers and policy processes show that they value public engagement and that it is important for students, faculty, and staff to think more broadly about the impacts of their research. Identifying, challenging, and supporting students who have strong qualities for successful policy engagement could, in turn, help shift the institutional culture around what is valued and supported. With better and more deliberate support for policy engagement, emerging leaders will advance both the knowledge and the action needed to overcome today’s grand sustainability challenges.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the entire COMPASS team, especially Estelle Robichaux, Meg Nakahara, Karen McLeod, Nancy Baron, and Erica Goldman for helping to shape ideas about this chapter. Also, thanks to Deb Markowitz and Taylor Ricketts for insightful comments on an earlier draft, Kristi Kremers for her deft editorial leadership, and Aerin Jacob and Kathy Zeller for sharing their stories of policy impact.

References

Akerlof, K. (2018). Congress’s use of science. Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Alberts, B., Gold, B. D., Martin, L. L., & Maxon, M. E. (2018). How to bring science and technology expertise to state governments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 115, 1952-1955.

American Association for the Advancement of Science. (2017). Connecting scientists to policy around the world: Landscape analysis of mechanisms around the world engaging scientists and engineers in Policy. Washington, D.C.

Balian, E. V., Drius, L., Eggermont H., Livoreil, B., Vanderwalle, M., Vandewoestjine, S., … Young, J. (2016). Supporting evidence-based policy on biodiversity and ecosystem services: Recommendations for effective policy briefs. Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice, 12(3), 431–451.

Baron, N. (2010a). Escape from the Ivory Tower. A guide to making your science matter. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Baron, N. (2010b). Stand up for science. Nature, 468, 1032-1033.

Baron, N. (2016). So you want to change the world? Nature, 540, 517-519.

Bednarek, A. T., Wyborn, C., Cvitanovic, C., Meyer, R., Colvin, R. M., Addison, P. F. E., … & Leith, P. (2018). Boundary spanning at the science– policy interface: The practitioners’ perspectives. Sustainability Science, 1–9.

Beier, P., Hansen, L. J., Helbrecht, L., & Behar, D. (2017). A how-to guide for co-production of actionable science. Conservation Letters, 10(3), 288-296.

Bernstein, M. J., Reifschneider, K., Bennett, I., & Wetmore, J. M. (2017). Science outside the lab: Helping graduate students in science and engineering understand the complexities of science policy. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(3), 861– 882.

Bipartisan Policy Center. (2018). Evidence use in congress. Washington, D.C.

Cairney, P. (2016). The politics of evidence-based policy making. 1st ed. New York, NY: Palgrave.

Cairney, P., & Kwiatkowski, R. (2017). How to communicate effectively with policymakers: Combine insights from psychology and policy studies. Palgrave Communications, 3(1), 37.

Cash, D. W., Clark, W. C., Alcock, F., Dickson, N. M., Eckley, N., Guston, D. H., … Mitchell, R. B. (2003). Knowledge systems for sustainable development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 100(14), 8086-8091.

COMPASS Science Communication, Inc. (2017). The message box workbook. Retrieved July 11, 2018 from https://www.COMPASSscicomm.org/

Cvitanovic, C., McDonald, J., & Hobday, A. J. (2016). From science to action: Principles for undertaking environmental research that enables knowledge exchange and evidence- based decision-making. Journal of Environmental Management, 183(3), 864–874.

Cvitanovic, C., Lof, M. E., Norstrom, A. V., & Reed, M. S. (2018). Building university-based boundary organisations that facilitate impacts on environmental policy and practice. PLOS ONE, 13(9), e0203752.

Evans, M., & Cvitanovic, C. (2018). An introduction to achieving policy impact for early career researchers. Palgrave Communications, 4, 88.

Kenny, C., Rose, D. C., Hobbs, A., Tyler, C., & Blackstock, J. (2017). The role of research in the UK Parliament, volume one. London: UK Houses of Parliament.

Lackey, R. T. (2006). Science, scientists, and policy advocacy. Conservation Biology, 21(1), 12-17.

Lacey, J., Howden, M., Cvitanovic, C., & Colvin, R. M. (2018). Understanding and managing trust at the climate science-policy interface. Nature Climate Change, 8(1), 22–28.

McKenzie, E., Posner, S. M., Tillmann, P., Bernhardt, J. R., Howard, K., & Rosenthal, A. (2014). Understanding the use of ecosystem service knowledge in decision making: Lessons from international experiences of spatial planning. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 32, 320–340.

Pielke, R. (2003). The honest broker. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Posner, S. M., McKenzie, E., & Ricketts, T. H. (2016). Policy impacts of ecosystem services knowledge. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113, 201502452.

Posner, S. M., & Stuart, R. (2013). Understanding and advancing campus sustainability using a systems framework. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 14(3), 264-277.

Posner, S. M., & Cvitanovic, C. (In Review). Evaluating the impacts of boundary-spanning activities at the interface of environmental science and policy: A review of progress and future research needs. Environmental Science and Policy.

Puritty, C., Strickland, L. R., Alia, E., Blonder, B., Klein, E., Kohl, M. T., … Gerber, L. R. (2017). Without inclusion, diversity initiatives may not be enough. Science, 357(6356), 1101-1102.

Rose, D. C., Mukherjee, N., Simmons, B. I., Tew, E. R., Robertson, R. J., Vadrot, A. B. M., … Sutherland, W. J. (2017). Policy windows for the environment: Tips for improving the uptake of scientific knowledge. Environmental Science & Policy.

Rowe, A., & Lee, K. L. (2012). Linking knowledge with action: An approach to philanthropic funding of science for conservation. Retrieved July 11, 2018 from https://www.packard.org/insights/resource/linking-knowledge-with-action-an-approach-to-philanthropic-funding-of-science-for-conservation/

Smith, B., Baron, N., English, C., Galindo, H., Goldman, E., McLeod, K., … Neeley, E. (2013). COMPASS: Navigating the rules of scientific engagement. PLOS Biology 11(4), e1001552.

Sutherland, W. J., Pullin, A. S., Dolman, P. M., & Knight, T. M. (2004). The need for evidence-based conservation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19(6), 305–308.