5

Dave Wilsey; Glenn Galloway; George Scharffenberger; Claire Reid; Karen Brown; Nina Miller; Katherine Snyder; and Larry Swatuk

Glenn Galloway is the Master’s in Sustainable Development Practice (MDP) Director at University of Florida

George Scharffenberger is the Master’s in Development Practice (MDP) Director at University of California Berkeley

Claire Reid is the Master’s in Development Practice (MDP) in Indigenous Development Director at University of Winnipeg

Karen Brown is an Affiliate Faculty Member and Director of the Interdisciplinary Center for the Study of Global Change at University of Minnesota

Nina Miller is the Master’s in Development Practice (MDP) Director at Regis University

Katherine Snyder is an Associate Professor and Master’s in Development Practice (MDP) Director at University of Arizona

Larry Swatuk is an Associate Professor and Master’s in Development Practice (MDP) Director at University of Waterloo

This chapter presents the origins of a graduate degree program designed for the sustainable development era. The idea for the Master of Development Practice (MDP) program emerged in 2007 and the first students matriculated in 2009. Today, the MDP degree program and the associated MDP Global Association include nearly 40 universities and countless partners among civil society and public and private sectors (Global Association, 2019). What follows details the conditions that led to forming a commission to explore the need for a new educational model and an overview of the key features of the sustainable development education model that resulted. There is then a reflection on the separate and shared experiences of the MDP program, viewed primarily through five programs in the North American region, followed by learning and adaptation that occurred, and how collaboration among programs fostered the evolution of a shared program. The chapter concludes with reflections on the strengths and challenges of the MDP model and the collaborative endeavor.

Recognizing Sustainable Development Education Challenges

In the early years of this millennium, those generally engaged in global sustainable development efforts and, in particular, the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), came to recognize glaring shortcomings in the way that complex global challenges were being conceived, analyzed, and addressed. At that time, John W. McArthur of Columbia’s Earth Institute wrote about a paradox: that the training for a major category of development professionals, though deep, was often quite narrow, and commonly misaligned with the breadth of responsibilities and the far-reaching influence of decisions made (International Commission on Education for Sustainable Development Practice (ICESDP), 2008). In light of this challenge, the MacArthur Foundation supported the creation of the International Commission on Education for Sustainable Development Practice (the Commission) and its mission to investigate current training for development professionals and to identify gaps and opportunities for improvement (ICESDP, 2008). The Commission consisted of a group of experts and practitioners from fields considered to be related to international development. In total, 20 individuals representing six regions participated in the commission, which was co-chaired by John W. McArthur and Jeffrey D. Sachs. The approach was inspired by a report written by Flexner (1910) that revolutionized medical training at a time when medical training was dominated by trade schools typically unaffiliated with institutions of higher learning and lasted only two years. The work of the ICESDP commenced in 2007 and culminated with a comprehensive report (ICESDP, 2008).

Situation Analysis (The “MacArthur Report”)

The Commission conducted a diagnosis of the current state of sustainable development training and practice. Under the guidance of its six regional coordinators, members undertook a series of consultations that engaged a cross-section of practitioners from universities, government and non-government agencies, financial institutions, and other development-focused organizations in Africa, East Asia, Europe, Latin America, North America, and South Asia (ICESDP, 2008). Consultations included interviews, regional conferences, surveys, and questionnaires. Consultations focused on professional education programs and training opportunities within sustainable development-oriented organizations. Throughout the process, commissioners explored training approaches related to problem-solving across disciplines and systematic skill-development for a range of core competencies.

High-level findings

The Commission’s effort highlighted a deficiency of cross-disciplinary knowledge and skills within the field of sustainable development. These findings suggested the need for a new type of “generalist practitioner,” one who understands the complexity of the interactions between areas of specialty (fields) and is capable of coordinating, translating, and implementing insights that emerged from subject experts. The Commission envisioned these individuals taking roles in government; non-governmental organizations; multilateral institutions, such as the United Nations; foundations; and the private sector.

This new cadre of professionals would complement the role of disciplinary specialists by navigating and forging connections between the “intellectual and institutional silos of specialized disciplines to develop integrated policy solutions that are scientifically, politically, and contextually grounded” (ICESDP, 2008, p. 4). In effect, these sustainable development practitioners would serve as the missing link in the professional sustainable development “ecosystem” (see Figure 1).

Recommendations

The Commission generated four, specific recommendations to address the general shortcomings identified through its effort. First, it recognized the need to establish a set of core competencies for sustainable development practitioners. These competencies would feature universal knowledge and skills essential to the integrative role envisioned and would also provide a sound foundation for the life-long learning that was perceived to be essential to ongoing success and relevance in a complex and dynamic world. Second, the Commission recommended the creation of the MDP program that would incorporate the core competencies and, notably, the interdisciplinary and integrative approaches that would distinguish program graduates. Moreover, it was suggested that MDP programs should be affiliated through the creation of a global network that attended to local contexts but also fostered the exchange of ideas and people for a more holistic cross-learning and professional development experience. Third, the Commission advocated for the creation of professional development programs capable of providing ongoing training to graduates of the degree program, as well as to a vastly greater number of professionals who are already in the field and are unlikely to participate in a formal, degree program. Finally, the Commission recommended the creation of a Secretariat responsible for the oversight and coordination of the network for the MDP degree program. The Secretariat would establish curriculum standards, represent the degree at major forums, and facilitate the network’s engagement with academic and professional communities. This chapter focuses on the Commission’s second recommendation, the MDP program, which also embodies and relates to elements of the Commission’s other three recommendations.

Developing a Shared Vision for Sustainable Development Education

The impact of any particular educational intervention relates not only to content and delivery, but also to timing. The decision to develop a masters level degree program focused on sustainable development practice surely factored in the benefits of targeting students who had already completed a university degree with a particular focus. That education, augmented with some early career experience, perfectly positioned prospective students for the objectives of the MDP degree.

The Master of Development Practice (MDP) Program

The Commission provided a template for an MDP degree program designed to “produce highly skilled ‘generalist’ practitioners prepared to confront complex sustainable development challenges” (ICESDP, 2008, p. 24). The vision for both the degree program and other professional development opportunities was shaped by four, guiding principles. Such training should aspire to prioritize:

- Integrated knowledge among health sciences, natural sciences, social sciences, and management;

- Lifelong learning fostered and facilitated through ongoing openness and access to professional training;

- Practical training utilized throughout the program to enhance the curricular experience;

- Partnerships across boundaries (geographic, cultural, etc.).

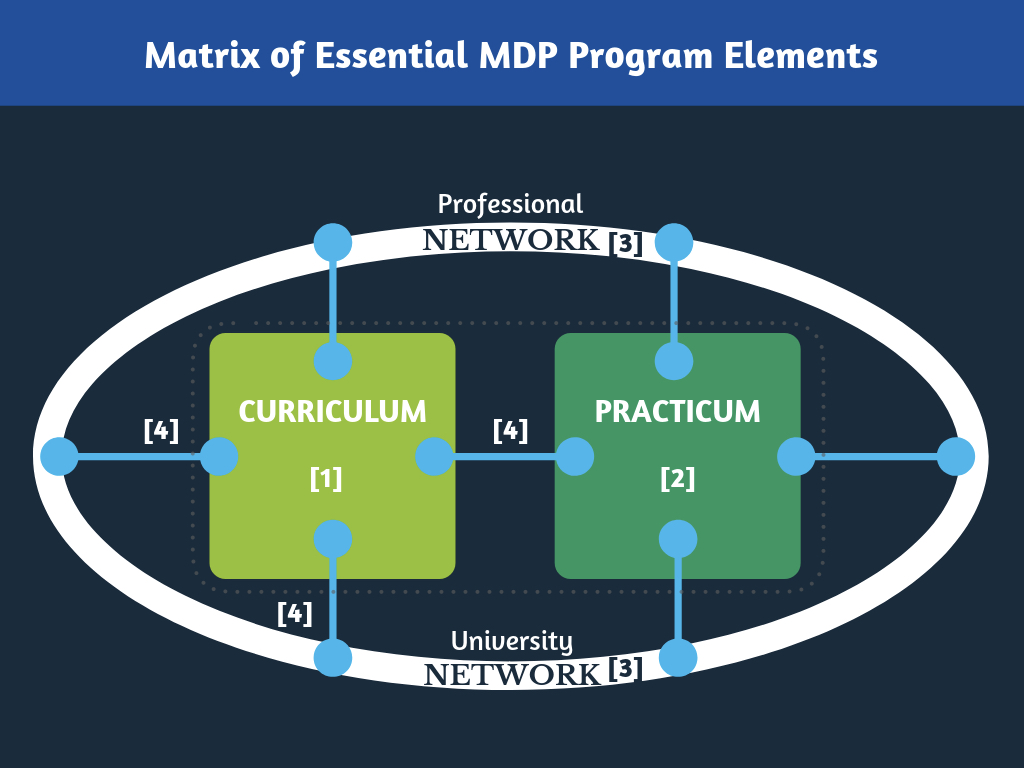

With these principles in mind, the Commission outlined a set of key components that they believed necessary for a master’s program (the MDP) intended to train practitioners to be the “missing link,” of sustainable development practice. Of these components, the following four seem essential to realizing the initial vision: 1) a common and interdisciplinary core curriculum; 2) extended field-based training or apprenticeships; 3) an active global network of programs and partners, and 4) enhanced classroom instruction featuring practical casework. Together, these four essential components of the MDP degree program serve as the building blocks for an innovative program model (see Figure 2) for the education of sustainable development practitioners.

A common, interdisciplinary core curriculum (Figure 2, [1]) is one essential element of the MDP degree program. The core curriculum draws upon the knowledge, skills, and other competencies found across the disciplinary landscape (see Figure 1). Required coursework across the university helps students to traverse this landscape to build a broad knowledge framework and skills toolkit and is an essential part of the MDP curricular experience. Likewise, the MDP core curriculum strives to build student capacity to connect and integrate across disciplines, for this particular competency is the hallmark attribute of the MDP alumnus. The ICESDP (2008) report states that “courses and learning activities [will] be anchored in an understanding of the inter-relationships among fields and course content [will] integrate cross-disciplinary approaches for sustainable development” (p. 25). Exactly how the MDP curriculum fosters disciplinary movement and integration is addressed in the next three program elements.

The MDP field practicum (Figure 2, [2]) represents the second essential element of the degree program. The field practicum complements campus-based learning through long-term placements, typically ranging from eight to twelve weeks, with practitioner organizations. The field practicum focuses on the application of learned knowledge and skills and on contextualizing knowledge and skills in situ, through close collaboration with program partners. The field practicum is a distinguishing and typically transformative experience in the development of MDP students. It draws heavily on cognitive knowledge and professional skills acquired prior to arrival and throughout the experience; it also draws upon and enhances the social-emotional attributes necessary to succeed and thrive as practitioners within complex, adaptive systems (Chan, 2001). Though the field practicum varies considerably by institution, most feature some combination of the following four characteristics:

- One or more practical training experiences in collaboration with partner organizations;

- Field-based academic programming that may include “formal” instruction by local actors and/or periodic engagement with campus faculty that focuses on supplemental knowledge, skill development, and experiential reflection;

- Organized social and cultural programming that may begin as early as the onset of the program and that likely continues through and after the field practicum; and

- A final report and/or set of project-driven deliverables that consolidate the knowledge gained, lessons learned, and implications for the challenge addressed and the work of the partner organization.

Competencies favoring successful classroom learning can differ from those that favor success in the field, resulting in the MDP core curriculum needing to foster student development in both realms. The MDP curriculum and field practicum are, therefore, complementary and mutually reinforcing elements. Individual degree programs may differ in how they address the curricular and logistical challenges associated with these two elements but, in almost all cases, learning opportunities associated with the field practicum extend well beyond the temporal boundaries of the experience itself. Development of these field-based experiences and the campus-based learning that precede and follow them relies heavily on a third essential element of the MDP program: the network.

The Global MDP Network (Figure 2, [3]) is the third essential component of the MDP degree program model. Two types of partners comprise the MDP network. The first is university partnerships which include those within a single institution (i.e., partnerships across disciplines and departments) and second are those between institutions offering the MDP degree. Both partnerships facilitate core operations and continuous improvement through the exchange of ideas, innovations, connections, and opportunities for student and faculty cooperation. University partnerships foster opportunities for both students and faculty to connect with other students and faculty across or between institutions. These linkages provide important opportunities for faculty to exchange relevant content and pedagogy within the network. Professional partnerships with sustainable development organizations complement university partnerships within the MDP network. Professional relationships can initiate from within the network (outreach by a program) as well as from the field (“inreach” by an organization) and can be short- or long-term.

This diverse and vibrant MDP network enlivens an educational model that depends on meaningful, field-based experiences with institutional and community partners. It facilitates the identification and movement of knowledge and skills central to the evolving practice of sustainable development and it fosters pedagogical exchange among MDP faculty. Finally, the network serves as a prospective employment network as students transition into their professional lives. The network’s multifaceted role in creating new linkages that foster the movement of knowledge, skills, and approaches to pedagogy make it an indispensable asset for the operationalization of the fourth and final essential component, the infusion of practical experience into the classroom.

Enhancing classroom learning with practical cases and experiences (Figure 2, [4]) provides a fourth and final fundamental program component, one that specifically targets the curriculum (Figure 2, [1]) but is substantially influenced by the field practicum (Figure 2, [1]) and network (Figure 2, [1]). Here, the emphasis lies in blurring the boundaries between classroom learning and practical experience through known and novel approaches. General examples include the use of prepared study cases; the use of real-world challenges as the focus for course work, often in close collaboration with professional partners; development of courses that specifically serve to interface with clients through real-world challenges; and the use of group-based training (or project teams) to mimic the multidisciplinary teams encountered in sustainable development-related fields. Moreover, the Commission emphasized that each individual course should, whenever possible, endeavor to link disciplinary knowledge and skills to practical policy, management, and other contemporary sustainable development challenges.

Master of Development Practice program affiliation is defined and determined by attributes and features held in common, aspects largely covered by the principles and essential components highlighted above and below. Each MDP program, however, is unique. Individual programs reside within different departments within their respective academic institutions. Each academic institution is, likewise, situated within a distinct context. The Commission report recognized and valued this complex reality, stating that programs may “modify the [program] to incorporate regional focus, to include a discipline-based specialization, or to provide complementary skills training within a specialized program of study. Any variation, however, should be anchored in the core competencies” (ICESDP, 2008, p. 36) and should adhere to the “essential components,” described above and represented in Figure 2. In other words, variation among MDP programs is both a necessary aspect of program design across place and time and an important part of the original vision.

Current State of the MDP Network

In the wake of the 2008 Commission report, an MDP degree program was established at three universities in 2009. This number quickly expanded to 15 programs in 2010 (see Table 1). Much of the initial delay in establishing programs stemmed from challenges associated with degree program approval at participating universities. Most of the pioneer programs were established with the financial support of a three-year startup grant from the MacArthur Foundation which supported program design, development, and staffing. Within three years, the global MDP network boasted 21 programs and, in 2018, 36 programs planned to offer the MDP degree. Annual enrollment has grown from roughly 300 students in 2010 to more than 500 in recent years. Growth in overall degree program enrollment tracks network growth, but individual programs with the capacity to expand have also seen notable growth in enrollment.

[table id=3 /]

Master of Development Practice Program Differentiation, Innovation, and Adaptation

This section highlights three important program dynamics that influence the characteristics of the individual programs as well as the overall network. Program differentiation refers to the ways that individual programs uniquely feature attributes specific to context and focus. Innovation and adaptation refer respectively to proactive and reactive responses to changes in context, focus, and experience that may affect differentiation through program divergence or convergence. All three dynamics represent important considerations for a network of programs seeking to retain a shared identity.

Program Differentiation

Productive tension between curricular standardization and differentiation across the network represents a central tenet within the MDP program vision. As indicated above, institutional differences – both intrinsic and contextual – make differentiation advantageous to adoption and survival. Over time, differentiation and differential adaptation present challenges to the overall integrity of the MDP degree; these issues will be addressed later in this chapter. From the outset, individual MDP programs took the model advanced by the Commission and MDP Secretariat and adapted it to local conditions, interests, and priorities. The result was a global network of differentiated programs espousing common guiding principles and essential components, such as the field practicum, and offering a curriculum that largely targeted common core competencies through different course configurations and pedagogical strategies. Additionally, many programs developed a unique focus within the broader realm of sustainable development. To showcase this differentiation, this section highlights a subset of MDP programs in the North American region.

[table id=4 /]

Program Innovation and Adaptation

This section showcases examples of program innovation and adaptation in two realms: the curriculum (on campus) and the field practicum (off campus). Each learning context presents unique and often complementary opportunities and challenges for practitioner development and both are essential. The former tends toward relatively higher levels of structure, control, and predictability whereas the latter tends toward substantially lower levels.

Within the curriculum

Though all organized learning experiences within the MDP program comprise the curriculum, this section refers primarily to classroom learning experiences, including both on and off campus components (i.e., community engaged learning). It includes curriculum focus – thematic lenses that bound or focus the MDP learning experience – as well as curriculum extensions – additional knowledge or skill sets that augment or complement the MDP curriculum. A third section, pedagogical innovations, focuses on course design and delivery.

Curriculum focus. While the preceding section highlights some program differentiations in North America, it is illuminating to take a closer look at one program that has uniquely adapted its focus to leverage and honor local resources and priorities. The University of Winnipeg’s MDP (UW-MDP) program focuses on Indigenous thoughts and worldviews and showcases the adaptability of the general MDP program model. First-year UW-MDP students take an integral, foundational course entitled Indigenous Thoughts and Worldviews. This full-year course brings the student into ceremonies, discussions, research, and conceptualization exercises that enable them to begin understanding Indigenous thoughts and worldviews from the perspective of an Anishinaabe Elder, his Anishinaabe colleagues, and those from other Indigenous traditions. Lectures and experiences help students gain insight into the core concepts of sustainable development, global sustainability, earth stewardship, and self-determination through Indigenous perspectives. Students carry the shared teachings beyond the classroom and many remark on how the course has transformed their way of thinking and being. The program is inherently interdisciplinary, not just because the specific course content intersects with the complexity of development topics but also because the course gives students the opportunity to learn from different learning traditions and knowledge systems; something that is absolutely vital to effective development work.

Curriculum extension. Most MDP programs encourage students to extend their curricular training through graduate minors and certificate programs focused on specific content areas or skills. The addition of a graduate minor or certificate allows students to signal interest and ability in a specific realm. Popular areas for additional training include public health, natural resource sciences and management, non-profit leadership and management, and program evaluation. Likewise, some MDP programs offer minors and certificates in development practice with the goal of attracting students from other programs and/or working professionals to core MDP courses. Master of Development Practice minors and certificates serve to extend the reach of the program principles, knowledge, and skills. Finally, some MDP programs offer joint degree options, allowing students to complete the full MDP curriculum and take a degree in some other area of interest. One example is the University of Florida’s joint MDP-Law degree, a program in which students simultaneously enroll in the Law and MDP programs. These students are particularly interested in the space where legal and development issues converge. Other programs have supported joint-degrees in public health, business, and various natural resource sciences.

Pedagogical innovation. Columbia University’s MDP program, situated within the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) developed a novel pedagogical format to address the challenge of teaching practical skills through engagement with development industry actors. The Development Practice (DP) Lab is a two-semester requirement in the first-year curriculum that focuses on a different set of competencies each semester (SIPA, 2013). The lab consists of 10 workshops, taught by guest practitioners from the field who use cases drawn from or related to core courses, to train students in skills and techniques required for problem appraisal and program design. Students learn how to use the key tools, techniques, and approaches employed by development organizations when diagnosing complex problems. Among the skills that are taught are stakeholder and institutional analysis; problem mapping and causal analysis; geographic information systems; logical framework analysis; and social media, advocacy, and agenda setting. The DP Lab began as a series of ad-hoc skills workshops and evolved into a full-year, required course, because of the perceived value. In addition to analyzing real-world cases, students have to complete exercises and work in teams to apply these skills to an integrated, country-level diagnosis for an actual campaign. The DP Lab has proven to be particularly effective in integrating concepts and skills from across different disciplines and in integrating MDP network partners with the campus curriculum. Other programs in the network have adopted the DP Lab model or certain key features.

Within the field practicum

The field practicum is perhaps the one aspect of the MDP program with the greatest variability. Adaptations and innovations to the relatively straightforward and somewhat undeveloped original idea of field-based training can be found across the MDP network. One innovation to the typical student summer experience is the differentiation between internships and student consultancies, with the latter generally favored by most programs. Consultancy-style placements mirror the type of professional engagements typically encountered by development practitioners upon graduation. Consultancy-style placements favor the development of the client and project management skills and greater familiarity with project scoping and related negotiations.

Taking a team approach to the field practicum is another innovation and adaptation. Several programs require team placements. These placements mirror the professional project environment and foster the development of interpersonal professional competencies. Team placements are also an adaptive strategy, in that they permit teams with members having varied skills (e.g., language, evaluation) and experience (e.g., topical, geographic) to collaborate on a project that might be otherwise beyond the capacity of a single student. Moreover, team projects foster collaboration across programs; several schools have formed project teams using students from multiple MDP programs. Since the inception of the MDP program, the sustainable development focus has shifted from an international focus (e.g., MDGs) to a global focus (e.g., Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the latter serving to better recognize the universality of sustainable development challenges and to balance the international and domestic considerations. The MDP field practicum requirement reflects this evolution. Programs increasingly encourage domestic placements to complement international ones. For example, both Winnipeg and Arizona encourage students to do one international and one domestic placement, often with nearby Indigenous nations. Likewise, many programs pair the in-situ field practicum requirement with an ex-situ capstone project, with the latter retaining a client-focused structure without an extended travel commitment. Additionally, most MDP programs partner with local organizations to enrich classroom-based learning experiences, bringing local challenges into conversations about global development and recognizing that the boundaries between local and global have blurred. Though the shift from MDGs to SDGs did not instigate this shift, it has certainly catalyzed it.

Market Positioning

Although the early vision for MDP graduates in the workforce was broad – reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of the program – it specifically focused on the integrative role of the professionals situated between policymakers and development actors in “the field.” This professional realm remains an important target for program alumni, but the experience of the previous eight years highlights the broader value of MDP training. The vision for program alumni has vertically expanded to include employees from the diffuse local to the (institutionally) more concentrated global. This expansion reflects two insights. First, over the last decade, sustainable development professionals have increasingly recognized that development is not a supply chain with ideas, finances, and effort emanating from central suppliers to dispersed consumers. So long as good work occurs at all points in the system, MDP practitioners have the potential to make valuable contributions everywhere. The graduates have discovered and shared that the integration of knowledge, skills, and professional behavior positions them well to take on a wide variety of professional challenges in the development field. Some graduates have opted to pursue work at the grassroots level with local community organizations and non-governmental organizations, while others have assumed the role of program officers in international organizations. To highlight the second insight, many MDP alumni have found opportunities in the private sector and at academic institutions. As private sector businesses have come to embrace sustainability and additional “bottom lines,” the skills acquired through MDP training have become increasingly valued by private industries, particularly those in partnership with public ventures. Likewise, as academic inquiry comes to focus more on complex, sustainable development challenges, the interdisciplinary, integrative skills found in the MDP program become assets to research teams. Increasingly, MDP alumni follow a path to doctoral research focused on complex, sustainable development challenges.

Fostering Strategic Evolution

With programs originating in different contexts and then innovating and adapting in response to different assets, opportunities, and challenges, the initial Commission report recognized the potential for programs to diverge to the extent that they do not retain functional commonality or compatibility. Several structures and systems were recommended to minimize this possibility and to strategically foster program co-evolution.

Mechanisms fostering strategic evolution

Since the inception of the MDP degree, programs in the network have had the option to meet annually, via the Global Summit. The venue for the Summit changes annually to encourage participation and representation. The Summit is the principal mechanism for establishing and strengthening cross-program relationships and partnerships, sharing of program successes and challenges, and introducing new institutions to the program and network. In 2013, the Global MDP Network became a co-sponsor of the inaugural International Conference on Sustainable Development (ICSD). Broadly, the ICSD provides a forum for academia, government, civil society, UN agencies, and the private sector to come together to share practical experiences and potential solutions to achieve the SDGs. For MDP programs, the ICSD provides another opportunity to connect across programs and regions and to share research completed by program faculty and students. Master of Development Practice faculty develop and moderate many of the ICSD research sessions. These events provide the principal means to operationalize the Global Network, via direct interaction between people and ideas. The MDP Secretariat plans and facilitates the Summit and ICSD meetings. The Secretariat also manages the process of recruiting new programs to the network and reviewing applications to ensure that they align with the MDP program’s shared principles and essential elements outlined in the Commission report.

More recently, a desire to increase the sharing of resources and cross-program learning led to the emergence of regional meetings within the Global Network. Programs in the North American region have met annually since 2016 to discuss successes, challenges, innovations, and opportunities for collaboration. These regional meetings have driven strategic program evolution within the region and across the network as regional insights get shared through the annual summit meetings and the ICSD.

Examples of strategic evolution

This section highlights examples of intentional actions taken by MDP programs – working collaboratively – to retain functional compatibility. The first section showcases the benefit of communication and engagement for the purpose of sharing (or disseminating) innovations and adaptations across the network. The subsequent section provides examples of co-creation of innovations and adaptations resulting from the intentional creation of proximity, time and opportunity.

Sharing Innovations and Adaptations

The Development Practice Lab. Columbia University’s presentation of its DP Lab (see above) at the 2016 Summit led to its adoption by the University of Minnesota in 2017. The DP Lab includes two important curricular pedagogical innovations. One is the pairing of real-world cases and guest practitioners to demonstrate the exploration of sustainable development concepts and methods. The other is the breakdown of the traditional course format into discrete, extended lab sessions, or workshops, that permit extended engagement and, when appropriate, community-engaged research. Both innovations present logistical challenges in the traditional university setting, but the sharing of ideas and experiences within and across programs has fostered the development of a successful, new course format.

Co-creation.

Program evaluation. University of Florida’s MDP program provided early leadership within the North American region in the area of program evaluation. University of Florida’s evaluation toolkit has been shared across the region and with the MDP Secretariat. Regional programs have used, adapted, and recirculated these tools and the results of individual program evaluations with the aim of improving overall degree quality through individual and shared program learning. In 2018, the North American region led an appreciative inquiry process (Cooperrider & Whitney, 2005) with members of the global network that focused on enhancing collaboration and affecting positive change. These efforts aim to facilitate the continued improvement of the degree program through intentional investments in collaboration across the network.

Professional competencies. Over the last few years, North America’s MDP programs have endeavored to better understand the general and specific competencies necessary for success in sustainable development. While a set of competencies was presented in the original Commission report, nearly a decade of program implementation, plus a changing global context, provide ample reason to revisit those initial assumptions. Ongoing engagement on this topic has led to an evolution from the early understanding that successful development practice requires diverse knowledge and skills plus practical experience to a more sophisticated conceptualization of essential competencies. Figure 3 presents the integrated MDP competencies framework used by the Minnesota MDP program, one version of a core competency framework that has emerged through this shared dialogue. This, and related efforts within the network foster continuous learning and curricular adjustments that ensure the MDP degree remains relevant and on the forefront of sustainable development education.

Collaborations around field practice. Field practice collaboration has been another important way that programs in the network maintain linkages and common strategies. There are several examples that demonstrate the ways that programs have collaborated in the field. In 2013, MDP program student teams from Minnesota and Université Cheikh Anta Diop de Dakar (Senegal) collaborated to explore capacity building strategies for local sustainable development organizations in Senegal. In 2015, MDP program students from the University of Florida, Emory University, and Columbia University formed a team to work with a SABMiller subsidiary, Bavaria S.A., in Colombia. The project explored corporate social responsibility. In 2016, MDP program students from the University of Minnesota and Emory University formed a team to work with Rainforest Alliance in Guatemala. The project explored global markets and value chains for non-timber forest products from the Maya Biosphere Reserve. In addition to specific project collaborations, each year the MDP Secretariat supports the development of an interactive map of field practicum projects across the program network, a resource that fosters countless faculty and student interactions.

From program to network partner. In 2016, the Berkeley MDP program hosted a visiting professor from the Institute for Food and Agricultural Development (IFAD). This partnership fostered IFAD’s exposure to the MDP program model and, in particular, the field practicum, ultimately leading to an opportunity to fund MDP program students across the global network to work on projects that supported IFAD projects around the globe.

Advancing the Common Vision for Sustainable Development Education

Nearly a decade of experience with the MDP program model and network provides the necessary experience and perspective for reflection on strengths and challenges. While the five programs highlighted in this chapter are but a small subset of the total, nearly all have been engaged members of the Global Association since its inception. Most of the strengths and challenges highlighted below were identified or endorsed by all of these programs and discussed extensively by a larger program subset at regional and international meetings.

Strengths of the Model

Perhaps the most universally acknowledged strength of the MDP program is the broad and integrated competencies framework that supports development of the whole professional, one capable of leading toward and through complex, dynamic contexts. The program model fosters investments in learning-across-disciplines and prioritizes engaged, experiential learning for effectiveness, adaptability, and resilience. Curricular and field-based experiences developed to support this framework and approach generate graduates with a breadth of understanding and the ability to work within and between areas of expertise, with a commitment to learning through practice. Similarly, MDP program graduates are capable of and comfortable with engagement and leadership from the grassroots to multinational organizations and have the capacity to move up and down this development “value chain.” Finally, the MDP Global Association and its member programs invest heavily in continuous organizational learning, investments that foster the very innovations and adaptations highlighted in this chapter.

Challenges of the Model

The MDP program model is not without its inherent challenges. As an interdisciplinary, practice-oriented degree, MDP programs sometimes struggle to develop and maintain broad institutional support, as the programs do not fit neatly into the disciplinary organization and incentive structure of the typical university (i.e., departments, faculty incentives, etc.). Similarly, programs within graduate schools that are principally organized around research often struggle to retain a focus on practice. Both of the preceding challenges also relate to a third concern for many programs: financial considerations associated with operating as a professional degree program, which typically cost more than graduate school tuition while at the same time making students less eligible or ineligible for opportunities commonly used to support costs (i.e., teaching and research assistantships). This issue is of particular importance for new and/or small programs, where enrollment volatility can easily push programs in and out of financial feasibility. Finally, for all the curricular and competency merits highlighted in the preceding paragraph, the degree sometimes seems more geared toward succeeding in a job than toward finding one. Graduates encounter challenges engaging a job market that values interdisciplinary and integration skills but maintains human resources systems that fail to recognize interdisciplinary degree programs.

Strengths and Challenges of Strategic Evolution

Just as there are strengths and challenges associated with the program model, there are also strengths and challenges associated with collaboration that is oriented toward innovation, adaptation, and exchange. The network effect is the most notable strength of the associated-program model. With each new, or newly engaged, MDP program, the number of opportunities for connection, exchange, and collaboration increases. In most cases, new institutions, programs, and faculty complement rather than compete with existing resources due to the interdisciplinary nature of sustainable development. Finally, the associated-program model fosters development of connections and relationships which generate positive social effects such as trust and mutual support. Nevertheless, the tension between collaboration and competition remains an important challenge, especially for smaller programs struggling to attract sufficient numbers of qualified candidates. While all programs struggle in some way or another to overcome time and other resource constraints associated with in-person collaboration, these costs can be disproportionately higher for smaller or newer programs. This chapter highlights some of the advantages of program differentiation but, in some cases, differentiation relates to meaningful resource disparities that can limit the innovation, adaptation, and exchange necessary for strategic evolution. Finally, structural differences between programs and their host institutions limit the attractiveness and feasibility of adopting ideas and innovations or even collaboration. These include differences in admissions requirements, academic calendars, tuition, and other practical realities that govern higher education. Often, such barriers can be overcome in specific instances but prove difficult to fully remove for recurring activities.

Looking to the Future

Since 2009, the MDP experience has been characterized by learning at the program level and cooperation and co-evolution at the network level. The original Commission report led to the development of an educational model and global network to support the success and growth of that model. While much has been learned from the experience, the MDP program remains relatively young. As the network and its member programs look to the future, it will become increasingly important to remain engaged with professional organizations that employ MDP program graduates and with the rapidly growing community of MDP alumni, a group rapidly approaching a critical mass in the sustainable development professional sector. Likewise, the educational “ecosystem” has changed since the publication of the Commission report. Other new degrees and degree variants feature attributes that once made the MDP degree novel. Retaining the focus on what happens outside the MDP degree and network is as important as focusing on what happens within. Just as we aspire to learn from and grow with our network partners, our network should aspire to do the same with other proponents of sustainable development education.

Over the first decade, it has been discovered that membership in an engaged, learning-oriented network confers benefits on individual programs and on the network as a whole. As new sustainable development programs emerge, established networks should strive to attract new members. Similarly, new programs should consider affiliation with existing networks or the creation of new alliances. Either way, the adaptations and innovations driven by unique program context and focus provide much needed insight in a field characterized by rapid and accelerating change in a complex world.

References

Chan, S. (2001). Complex adaptive systems. ESD 83, Research Seminar in Engineering Systems. October 31, 2001/November 6, 2001. Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA.

Cooperrider, D. and Whitney, D. (2005). Appreciative inquiry: A positive revolution in change. San Francisco, California: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Flexner, A. (1910). Medical education in the United States and Canada: A report to the Carnegie Foundation for the advancement of teaching. Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin No. 4. 364 pages.

Global Association of the Masters in Development Practice. (2019). Global MDP Association Partner MDP Institutions. Retrieved from http://www.mdpglobal.org/.

International Commission on Education for Sustainable Development Practice. (2008). Report from the International Commission on education for sustainable development practice. New York, New York: Earth Institute at Columbia University. 100 pages.

Miyamoto, K., Huerta, M. C., and Kubaka, K. (2015). Fostering social and emotional skills for well-being and social progress. European Journal of Education, 50(2), 147-159. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12118

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2015). Skills for social progress: the power of social and emotional skills. Paris: OECD Publishing. 142 pages. DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264226159-en

School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA) (2013). New MPA-DP lab enhances learning environments. Retrieved from https://sipa.columbia.edu/news/new-mpa-dp-lab-enhances-learning-environments.

University of Arizona. (2019). Master of Development Practice. Retrieved from https://geography.arizona.edu/masters_development_practice

University of California-Berkeley. (2019). Berkeley MDP. Retrieved from https://mdp.berkeley.edu/

University of Florida. (2019). Master of Sustainable Development Practice. Retrieved from https://www.mdp.africa.ufl.edu

University of Minnesota. (2019). Master of Development Practice. Retrieved from https://www.hhh.umn.edu/masters-degrees/master-development-practice

University of Winnipeg. (2019). Master of Development Practice in Indigenous Development. Retrieved from https://www.uwinnipeg.ca/mdp/