7

Shanda L. Demorest and Teddie M. Potter

Teddie M. Potter, PhD, RN, FAAN, is a Clinical Professor at the University of Minnesota’s School of Nursing

For many, the word crisis connotes a negative or despair-inducing scenario, whether referring to human or environmental health. Curiously, the Oxford Dictionary (2018) defines a crisis as “the turning point of a disease when an important change takes place, indicating either recovery or death.” Guided by Oxford’s definition, it follows that recovery from planet Earth’s “disease” of climate change is possible. The Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change (2015) maintains that climate change is both the world’s largest public health threat and a grand opportunity for humanity to overcome a colossal challenge by working together toward necessary societal change. Given the right leadership, crises can indeed prompt growth and bursts of creative solutions.

Framing language is imperative in developing the next generation of sustainability leaders and changemakers. Given that the Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change (2015) views climate change as both a danger and an opportunity, it follows that climate change education, in the context of public health, should be similarly approached. However, there is evidence that suggests that, when people are faced with a challenge as daunting as the planetary health crisis of climate change, it is not unusual for them to feel confused about where to begin, too paralyzed to take action, or—worst of all—overwhelmed by despair (Heald, 2017). Thus, while the authors of this chapter recognize the urgent human, animal, and planetary health threats that climate change poses, this chapter is primarily written through the lens of opportunity. Approaching climate change via hopeful interdisciplinary partnerships prepares and positions emerging sustainability leaders for long-term success.

What follows in this chapter is an account of an interprofessional team of health educators at the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center who had a mutual understanding of the Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change’s (2015) model; namely, that climate change is simultaneously a dangerous health threat and a unique opportunity for partnership, innovation, and joined forces.

The Connection Between Climate Change and Sustainability

First, it is necessary to clearly delineate the relationship between climate change and sustainability. According to the World Meteorological Society (WMO, 2017), climate change is defined as changes in the “average weather,” which include “temperature, precipitation, and wind” (para. 1). While weather changes continuously, climate change involves unpredictable, widespread regional or global fluctuations in weather over an extended period – usually over about three decades (WMO, 2017).

Furthermore, it is important to highlight that the greatest notable changes within the global climate have occurred since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution when there was a widespread introduction of fossil fuel-based energy use. This mode of energy production has resulted in a steep increase in global emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC], 2013). Based on the direct positive correlation of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions and global temperature increase resulting in climate variability, climate change has widely been accepted as human-caused. In fact, in a recent survey of authors of nearly 70,000 published, peer-reviewed, scientific articles, there was over a 99.99% consensus that climate change is caused by human activity (Powell, 2016).

Globally, the unpredictable fluctuations in climate over the last few decades have contributed to extreme high and low temperatures, more frequent and more powerful precipitation and storms, a rising sea level, and ocean acidification. These changes have had both direct and indirect impacts on Earth’s living organisms (IPCC, 2013). Bluntly stated, climate change endangers the sustainability of life on planet Earth. Moreover, given that climate change is primarily human-caused, it follows that sustainability on Earth is directly threatened by human actions. If we are serious about supporting future life on this planet, sustainability leadership is non-negotiable.

There are many strategies to address climate change through the sustainability lens, which is based on the principle that “everything we [humans] need for our survival and well-being depends, either directly or indirectly, on our natural environment” (Environmental Protection Agency [EPA], 2016). This same premise applies to all non-human life on Earth. Sustainability, therefore, is relevant and necessary in every discipline, for every scholar, and for every change agent. The EPA’s definition of sustainability involves “survival” and “well-being” – both of which are deeply interwoven with health. Thus, by including sustainability and climate change efforts in their scholarship and practice, health professionals, in particular, have the opportunity – and responsibility – to lead.

‘One Health’ Impacts of Climate Change

In recent years, the term ‘One Health’ has been used to describe the connection between the health of living organisms and the health of the environment (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2018). The One Health framework expands upon the definition of sustainability shared earlier through the inclusion of non-human animals. Based on this relationship, it follows that if climate change threatens sustainability, it also threatens ‘One Health’ – the health of the environment, animals, and humans.

Climate Change and the Environment

Fundamentally, the increase in the consumption of fossil fuels has altered the composition of greenhouse gases in the Earth’s atmosphere (IPCC, 2013). Earth’s oceans, which absorb carbon dioxide, have warmed and become more acidic over time due to a greater ability to absorb gases (IPCC, 2013). This global oceanic warming has resulted in an average sea level rise of about ⅓ of a centimeter per year. This rate is expected to increase dramatically in the coming century (IPCC, 2013). In fact, experts estimate an average sea level rise of 28-98 centimeters by 2100, depending on future greenhouse gas emissions (IPCC, 2013). Severe precipitation and storms cause massive damage to forests, bodies of freshwater, and soils. Oceanic changes and precipitation are not the only climate change effects that impact the environment; extreme heat has contributed to widespread droughts on all landmass continents, as well as an increase in forest fires (IPCC, 2013). Plant species are unable to migrate or adapt quickly enough, via seed dispersal and other methods of propagation, to outpace these geographic changes. Nearly 70% of plant species in the Amazon Rainforest are at risk of extinction by 2100 (World Wildlife Foundation [WWF], 2018). Furthermore, the plant adaptation challenges at hand have major implications for food security across the globe. Climate change has harmful effects on the very ecosystems that all living things rely upon.

Climate Change and Animal Health

Within the One Health framework, humans are considered separate from all other animals. However, non-human animal (including insect) health is drastically impacted by climate change in a myriad of ways. Based on a widespread literature review, Dr. Elizabeth Kolbert (2015) estimates a 20 to 50% reduction in all species on the planet by the end of the 21st century – citing climate change as one of the premier causes. The World Wildlife Foundation (2018) shares similar estimates, with even more specific and disturbing figures, such as 96% of tiger breeding grounds in the Sundarbans being submerged by rising sea levels and 60% of all species in Madagascar facing local extinction. Rising temperatures and fluctuating precipitation patterns lead to the emergence, re-emergence, and spread of bacterial, viral, fungal, and other diseases, both non-vector- and vector-borne, that animals have little or no protection against. In addition, ocean acidification results in physiological assaults to animals whose bodies cannot adapt quickly enough. One only needs to momentarily think about the circle of life to understand the vast global implications of animal species extinction.

Climate Change and Human Health

Throughout the Anthropocene, humans have driven massive climate and environmental change. Over the past few decades, a quickly expanding body of research supports the premise that the relationship between humans and the environment is a two-way street (CDC, 2016; Kolbert, 2015; National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [NIEHS], 2017; Planetary Health Alliance, 2018). Humans are harming the climate – and now the climate is responding. Local, regional, national, and global health agencies have identified a multitude of ways climate change is deleteriously impacting human health. Specifically, weather fluctuations due to climate change exacerbate chronic conditions such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases (CDC, 2016; Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, 2017; NIEHS, 2017; World Health Organization [WHO], 2018). Climate change endangers human health via extreme heat, vector-borne diseases such as Lyme disease and Zika virus, extreme weather-related injuries and deaths, and changes in food and water supply (CDC, 2016; Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, 2017; NIEHS, 2017; WHO, 2018). In addition, the projected sea level rise does not bode well for nearly 50% of the U.S. population expected to live in high-density coastal areas by 2020 (National Ocean Service, 2018). Furthermore, indirect impacts such as mental health challenges, forced migration, and civil conflict are increasing in frequency (CDC, 2016). As with most other “health” issues, impacts of climate change are not felt proportionally across the human spectrum (WHO, 2018). The most vulnerable among us — the impoverished, the homeless, and the elderly, as well as children, women (Halton, 2018), and some communities of color — experience greater negative health effects of climate change (WHO, 2018).

It is known that health providers are widely viewed as trusted professionals. According to Gallup (2018), nurses have been ranked as the most trusted professionals in the U.S. for the last 16 years, with other members of health care teams not far behind. Therefore, educating health professionals about the health impacts of climate change so they can, in turn, share the information with their clients may be the most effective way to inspire individuals to take action.

As the authors of this chapter have argued in this section, climate change impacts all aspects of sustainability and ‘One Health.’ While it is critical for health professionals to engage in climate leadership, it is not enough to address climate change in a disparate fashion. When it comes to the health of the environment, animals, and humans, it is essential that multiple disciplines work together to collectively rewrite the climate change narrative and innovate solutions to address this global challenge.

Interprofessional Leadership in Addressing Climate Change

As previously mentioned, complex problems require complex solutions. One discipline alone will not be able to create viable climate change solutions. Instead, society needs to shift its understanding from old patterns of siloed research and fieldwork to new patterns of collaboration. ‘One Health’ is a start on this path, but even the aspirations of ‘One Health’ can be thwarted when adherents practice from a multidisciplinary, rather than a transdisciplinary, mindset.

Disciplinary, Multidisciplinary, Interdisciplinary, and Transdisciplinary Thinking

Disciplinary thinking has been the traditional approach to teach and scholarship within the academy. Each discipline obtains its own grants and funding, conducts its own research, and disseminates research findings through journals, conferences, books, and curriculum specific to that field. A multidisciplinary approach invites disciplines to apply knowledge from other fields to their own discipline. Essentially, one or more disciplines work to advance knowledge in a shared field, but they still apply knowledge gained from other disciplines within their own disciplinary boundaries (Choi & Pak, 2006). An interdisciplinary approach deepens levels of collaboration. One might see teams from various disciplines working on the same research project or co-authoring publications. There is a growing number of interdisciplinary journals such as the Journal of Interprofessional Education and Practice (JIEP) as well as interdisciplinary conferences such as the International Conference on One Medicine One Science (iCOMOS).

Ultimately, the most advanced form of collaborative practice is transdisciplinarity. “Transdisciplinarity integrates the natural, social and health sciences in a humanities context, and transcends their traditional boundaries” (Choi & Pak, 2006, p. 351). The World Health Organization underscores the potential of this form of collaboration:

Many health workers believe themselves to be practicing collaboratively, simply because they work together with other health workers. In reality, they may simply be working within a group where each individual has agreed to use their own skills to achieve a common goal. Collaboration, however, is not only about agreement and communication but about creation and synergy. Collaboration occurs when two or more individuals from different backgrounds with complementary skills interact to create a shared understanding that none had previously possessed or could have come to on their own. (WHO, 2010, p. 36).

Effective climate change mitigation and adaptation initiatives require educators to think beyond not only disciplinary boundaries but also geographical, political, economic, and social boundaries. The planetary health crisis calls for an “all hands on deck” approach, but change agents that adopt this level of collaboration and partnership will indeed “create a shared understanding that none had previously possessed or could have come to on their own” (WHO, 2010, p. 36).

The following case study illustrates a transdisciplinary approach to interprofessional climate change education. The result is that all health professional students at the Academic Health Center (ACH) graduate with a basic understanding of their role in climate change prevention and care for impacted populations.

1Health at the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center

For nearly half a century, the AHC at the University of Minnesota has been a significant leader of interprofessional education in the United States. In 2009, the AHC developed a 1Health vision and plan. 1Health is not to be confused with One Health – although they both promote interdisciplinary collaboration. The 1Health initiative at the University of Minnesota:

Prepares students in allied health, dentistry, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, public health, veterinary medicine and other related programs, such as social work, to develop the skills needed for success in interprofessional collaborative practice. 1Health challenges students throughout their academic careers to understand and value the importance of teamwork, communication, and collaborative care as they grow into their roles as health professionals. (University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Office of Education, n.d.).

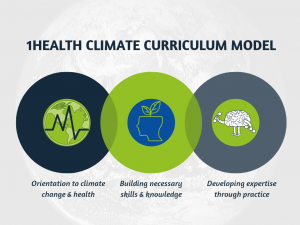

There are three phases of 1Health:

- Phase I – Orientation: The Foundations of Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration (FIPCC) course provides students across the AHC with an introduction to interprofessional education concepts and teamwork skills.

- Phase II – Necessary Skills: This prepares students for rotations in the practice setting by providing them with additional skills and experiences.

- Phase III – Expertise in Practice: Real-world learning through authentic experiences builds on students’ knowledge and ability to contribute to team-based care.

Interprofessional Climate Change Curriculum: A 1Health Initiative

The three-phase approach to interprofessional education highlighted above is an exemplary model used to respond to student-driven change and to transcend disciplinary boundaries related to climate change education. For instance, at the University of Minnesota, graduate and health professional students are leading the way in interprofessional action on climate change.

Background. In 2016, eight nursing and medical students learned of each other’s passion for climate action. Borrowing from the vision and mission of Health Professionals for a Healthy Climate [HPHC, 2018], a community-based interdisciplinary health professional organization, the students formed their own official student group at the university entitled, Health Students for a Healthy Climate [HSHC]. Over the course of two years, HSHC burgeoned into a robust group consisting of health students from the schools of nursing, medicine, dentistry, public health, and veterinary medicine. Examples of HSHC activism include legislative letter writing, lobbying, and marching to support science and protest fossil fuel-based energy, as well as hosting monthly social “Climate Conversations” and student and public lectures.

While the interprofessional approach and climate focus of HSHC were both unique for health student groups at the university, the students believed they had the capacity to make a greater impact. In the spring of 2017, through the guidance of nursing and medical faculty, HSHC crafted a survey to inquire about students’:

- Knowledge about the health impacts of climate change;

- Beliefs about the direct impacts of climate change on patient health;

- Experiences with health curricula including climate change content; and

- Levels of desire to see climate change content in health curricula.

One hundred and thirty-nine students from six health professions (nursing, medicine, dentistry, public health, veterinary medicine, and pharmacy) responded to HSHC’s survey. Students reported that they knew “only a little” (32%) or “a moderate amount” (47%) about the health impacts of climate change. However, the survey respondents also indicated that they believe climate change directly impacts patient health “a great deal” (53%) or “a moderate amount” (34%). Forty-six percent of respondents reported that only “a few” of their courses in their health program included content about the connections between climate change and health, whereas 53% of respondents reported that “none” of their courses included climate and health content. Finally, 43% of those surveyed indicated they had a desire for their curricula to address the health impacts of climate change “a great deal,” while 40% indicated they had “a moderate amount” of desire for climate curricula within their health programming (Demorest, n.d.).

The survey illuminated a major opportunity for University of Minnesota health programming. The consumers of health professional education had spoken – interprofessional health students wanted to learn about the health impacts of climate change. In a strategic effort led by HSHC and nursing and medical faculty advisers, the survey results were presented at an executive leadership council made up of the Associate Deans of each health program at the university. Following a discussion of the opportunities that climate change curriculum offered for innovation and leadership, the executive leaders unanimously agreed to authorize a team to use a phased 1Health approach to address the gap in climate change education (see Figure 1).

Phase I: Orientation. The goal of Phase I is to orient or introduce all AHC health profession students to climate change as a health issue. The preexisting FIPCC course is the ideal vehicle. The FIPCC course brings students from all the health care disciplines together for a series of six facilitated classes during the first semester of their professional education. The students are assigned to small groups with representation from each discipline. Discussions are designed to promote learning from anFd about each other so students will be better prepared for interprofessional practice. Topics include roles and responsibilities, health systems, teamwork, ethics, leadership, and other health system concepts shared across the disciplines.

Climate change content was specifically designed to be incorporated into the health systems module. One objective was modified to, “Use the complex health impacts of climate change as a case study to demonstrate the intersection of health and education,” (University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Office of Education, 2017) in order to address climate change content.

Facilitators prepared in advance by watching three short videos on climate change and reading four short summaries from climate change literature (see Table 1).

[table id=1 /]

Foundations of Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration students were asked to prepare for the module by watching the video APHA’s Year of Climate Change and Health. They were asked to come prepared to discuss, “How can your profession impact climate change mitigation (prevention) and adaptation (treatment of consequences)” (University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Office of Education, 2017)?

On the actual day of the course, interprofessional student groups were asked to watch two videos then take part in an activity (see Table 2).

[table id=2 /]

Foundations of Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration proved to be a very effective vehicle for orienting all the health professional students to the topic of climate change and health. Over 40 facilitators and 1,100 health profession students from 17 health programs on five different campuses learned basic facts about climate change and health.

Phase II: Necessary Skills – Development of Climate Change and Human Health Interprofessional Content (see Figure 1). The first step of Phase II involved recruiting ‘Climate Champions’ from every school and college in the AHC. Recommendations came from the Associate Deans, as well as the Director of Education, for the AHC. The ‘Climate Champions’ represented the following disciplines and departments:

- School of Nursing

- School of Medicine

- College of Pharmacy

- Veterinary Medicine

- Occupational Therapy, Center for Allied Health

- Public Health

- Medical Laboratory Sciences

- Dentistry

- The Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility

- AHC Office of Education

‘Climate Champions’ are respected thought leaders in their units. Their primary responsibilities are to assess the curriculum for their unit to determine the best place(s) for the addition of climate change content, to co-create climate change curriculum and provide advice on the learning needs of their students, to disseminate the climate curriculum in their schools once it has been created, and to be a resource to faculty and staff as the climate change curriculum is implemented.

Within a year, the curriculum was created, reviewed, revised, copy-edited, and approved for dissemination. The final product is entitled Climate change and health: An interprofessional response (University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Office of Education, 2018). It consists of an introductory slide deck and eight focused slide decks on climate-related issues and their associated health impacts. Some of the focused slide decks include increasing severe weather, increasing allergens and air pollution, and the rise of extreme heat, all of which impact safety, exacerbate cardiopulmonary illnesses, and threaten food and water quality. These decks are designed to be implemented throughout the AHC by the ‘Climate Champions.’ The decks are also available to the general public through the University of Minnesota Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility under a Creative Commons license.

Phase III: Planning and Project Examples. Orienting and teaching health professional students about the health impacts of climate change are important steps in increasing awareness. However, knowledge alone is not enough. Without actions to adapt to or mitigate the health effects of climate change, change cannot occur. At the University of Minnesota AHC, the goal is to prepare students to lead climate change action which requires students to develop the skills needed to implement climate change-related projects while they are in their health programs. This implementation occurs in Phase III of the 1Health climate change curriculum, which is currently in the development-pilot stage (see Figure 1).

One approach health professional students can use to address climate change is to focus on reducing the carbon footprint of health care and health education. Formalized student environmental sustainability projects involve a deeper level of collaboration, one beyond the University AHC. ‘Climate Champions’ leading the Phase III initiative connect students who self-identify as having an interest in environmental projects with environmental leaders in local health organizations at a community level. Typically, environmental sustainability in health organizations falls within the scope of directors or managers who were trained in traditional health profession roles or otherwise. Therefore, students who participate in sustainability or climate action projects have the opportunity to learn from leaders in their own fields or outside their health disciplines – many of whom are not currently practicing health professionals. Thus far, students have participated in Phase III pilot projects that have focused on implementing the following environmental sustainability initiatives:

- Forming Green Teams in health care and health education settings

- Reducing the use of fossil fuels in health care and health education settings

- Developing carbon footprinting protocols for hospitals and clinics

- Reducing waste in patient care, organizational, and educational settings via increasing re-using, recycling, and composting rates

- Reducing unnecessary use of anesthetic gases with high global warming potentials

- Educating staff and leadership about regional impacts of climate change

- Developing patient education on climate change and health in Minnesota

Over time, the aim of Phase III is to support community-based projects for students who present a penchant for environmental or climate action in each health program. By carrying out these real-life projects in interprofessional teams comprised of health students and current health professionals, students learn the value of cross-sector collaboration. Connecting students and practicing health professionals around the issues of climate and health has the unique advantage of preparing students to transition to professional practice with a holistic understanding of the health impacts of climate change along with their disciplinary knowledge. Furthermore, students who work on projects with the goal of adapting to or mitigating climate change contribute to the ultimate global goal of reducing the effects of climate change.

Lessons Learned

To date, the team has only received student evaluations regarding Phase I work. Of the over 1,100 students who participated in the orientation about the health impacts of climate change and the relevance to interprofessional collaboration, nearly 800 responded. It is important to recognize that the delivery of the orientation’s content varied and was impacted by the skill levels of 40 different facilitators. A student in public health nutrition commented, “This session was my favorite because in some way we were able to relate every professional role to having a part in climate change” (Sick, n.d.). Additionally, a speech-language pathology student shared, “I had never really considered the effects of climate change on health before, and I thought our discussions in small and large group were really informative” (Sick, n.d.).

On the other hand, there are further opportunities for ‘Climate Champions’ to refine the work, such as preparing facilitators to be more inclusive of all health professions. One audiology student commented that the climate change case was “not related to [their] field. What impact does climate change have on the auditory or vestibular system?” (Sick, n.d.). Furthermore, the debate of the existence of anthropogenic climate change remains. As one medical student stated, “Incorporating climate change, while important, seemed forced to certain students who deny the process or fail to recognize the severity” (Sick, n.d.).

While the survey results will inform work moving forward, this process is generalizable for multiple contexts. The following lessons learned from this experience may help inform others implementing similar initiatives:

- Never underestimate the power of students’ voices. When students mobilize and coordinate their requests, they can drive change. Therefore, working with student leaders to measure their interest in an initiative is an essential first step.

- Once students see a need for change, it is important that they directly work with leaders who have the authority to authorize that change.

- The next step is to create a diverse team to design the initiative. Effective change is not mandated nor does it thrive in hierarchies. Effective change occurs when people from diverse disciplines with diverse knowledge and experiences work in partnership to co-create solutions to our grand challenges.

- Effective change also requires a commitment to iterate. The first model is bound to require modifications based on feedback. Each new iteration can improve the effectiveness of the model.

- Be sure to keep stakeholders (i.e., students and administrators) informed of progress on the initiative. People want to see movement so they can support movement.

- Keep things as simple as possible. Layers of complexity are rarely necessary for an initiative to succeed.

- Share! Climate change is an “all hands-on-deck” issue. If you develop a best practice or create an effective model, pass the knowledge on to others.

This interprofessional climate work presented new challenges and opportunities that the faculty had not previously encountered. It required a great deal of patience and commitment to find dates and times when representatives from all the professions could meet. However, once ‘Climate Champions’ had been designated, one of the greatest take-aways was the sheer joy of working across boundaries. Not only did educators walk away with a better understanding of the incredible work being done across the AHC; they also came to recognize that transdisciplinary interprofessional collaboration makes things that previously seemed impossible possible. When leaders collaborate on transdisciplinary projects, siloed and hierarchical thinking is no longer palatable.

Next Steps

Knowing that during development and implementation of the curriculum challenges would be encountered, the ‘Climate Champion’ team deliberately incorporated the two I’s: Innovation and Iteration. In fact, innovation and iteration are the two primary components of design thinking (Brown & Wyatt, 2010). Specifically, “design thinking taps into capacities we all have but that are overlooked by more conventional problem-solving practices” (Brown & Wyatt, 2010, p. 33). Thus, the authors of this chapter used the design thinking approach during each of the three climate change curriculum phases to foster an unconventional and flexible process with valuable results. All three phases will continue to undergo further iterations in response to emerging trends and new climate change mitigation and adaptation knowledge.

In addition, the authors plan to use this experience to move closer to true transdisciplinary collaboration. While the value of sharing this story in academic journals of respective professions is understood, the authors aim to find dissemination opportunities that challenge disciplinary thinking. The authors hope to stretch, or even break, traditional boundaries that have, thus far, thwarted progress on climate change. They aim to weave the health sciences together in the context of humanity and nature (Choi & Pak, 2006). Support for transdisciplinary collaboration on climate work is steadily growing as evidenced by organizations such as WHO (2010) and the Planetary Health Alliance (2018). Through the dual lens of hope and opportunity, the ultimate aim is to transcend disciplinary boundaries to find effective and sustainable solutions for climate change.

References

American Public Health Association [APHA]. (2017, Mar 9). APHA’s year of climate change and health [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/6NRQshz3iAQ

Brown, T., & Wyatt, J. (2010). Design thinking for social innovation. Stanford Social Innovation Review, Winter 2010, 31-35.

Centers for Disease Control [CDC]. (2016). Climate effects on health. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/climateandhealth/effects/default.htm

Centers for Disease Control [CDC]. (2018). One Health basics. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/basics/index.html

Choi, B., & Pak, A. (2006). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: Definitions, objectives, and evidence of effectiveness. Clinical and Investigative Medicine, 29(6), 351-364.

Demorest, S. (n.d.). Survey of health professional students regarding climate change curriculum. Unpublished manuscript. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

ecoAmerica. (2016). Let’s talk health and climate: Communication guidance for health professionals. Climate for Health, Washington, D.C. Retrieved from https://ecoamerica.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/3_letstalk_health_and_climate.pdf

Environmental Protection Agency [EPA]. (2016). Learn about sustainability. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/sustainability/learn-about-sustainability

Gallup. (2018). Nurses again outpace other professions for honesty, ethics. Retrieved from https://news.gallup.com/poll/245597/nurses-again-outpace-professions-honesty-ethics.aspx

Global Climate and Health Alliance. (2014, Apr 3). Climate change: Our greatest health threat, or our greatest opportunity for better health? [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/ZrwqwuNNX4I

Halton, M. (2018). Climate change impacts women more than men. Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-43294221

Heald, S. (2017). Climate silence, moral disengagement, and self-efficacy: How Albert Bandura’s theories inform our climate-change predicament. Environment: Science and Policy for Sustainable Development, 59(6), 4-15, https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00139157.2017.1374792

Health Professionals for a Healthy Climate [HPHC]. (2018). Our vision. Retrieved from https://www.hpforhc.org/vision–mission.html

Hellerstedt, W. L. (2017, Dec). What’s bad for the planet is bad for people: The health consequences of climate change. Healthy Generations, Spring 2017, 26-33.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [IPCC]. (2013). Climate change 2013: The physical science basis. Retrieved from http://www.climatechange2013.org/images/report/WG1AR5_ALL_FINAL.pdf

Kolbert, E. (2015). The sixth extinction: An unnatural history. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company.

Lancet Commission on Health and Climate Change. (2015). Briefing for the global health community. Retrieved from http://www.lancetcountdown.org/media/1057/briefing-for-the-global-health-community.pdf

The Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health. (2017). Medical alert! Climate change is harming our health. Retrieved from https://medsocietiesforclimatehealth.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/gmu_medical_alert_updated_082417.pdf

Minnesota Department of Health. (2014). Minnesota climate change vulnerability assessment 2014 executive summary. Retrieved from https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/environment/climate/docs/ccva_execsum.pdf

National Geographic. (2015, Dec 2). Climate change 101 with Bill Nye [Video File]. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/EtW2rrLHs08

National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences [NIEHS]. (2017). Climate and human health. Retrieved from https://www.niehs.nih.gov/research/programs/geh/climatechange/index.cfm

National Ocean Service. (2018). What percentage of the American population lives near the coast? Retrieved from https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/population.html

Oxford University Press. (2018). Crisis. Retrieved from https://www.lexico.com/en/definition/crisis

Planetary Health Alliance. (2018). Our mission. Retrieved from https://planetaryhealthalliance.org/mission

Powell, J. L. (2016). Climate scientists virtually unanimous: Anthropogenic global warming is true. Bulletin of Science, Technology, and Society, 35(5-6), 121-124. https://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0270467616634958

Sick, B. (n.d.). Overall foundations in interprofessional communication & collaboration student ratings 2017-2018. Unpublished manuscript. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN.

University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Office of Education [AHC]. (n.d.). 1Health: UMN interprofessional education program. Retrieved from https://www.ahceducation.umn.edu/1health-setting-new-standard-interprofessional-education

University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Office of Education [AHC]. (2017). FIPCC 2017 Facilitator Guidebook. Twin Cities, MN: University of Minnesota.

University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Office of Education [AHC]. (2018). Climate change and health: An interprofessional response. Retrieved from https://globalhealthcenter.umn.edu/education/climatehealth

World Health Organization [WHO]. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education and collaborative practice. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. [WHO]. (2018). Climate change and health. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

World Meteorological Society [WMO]. (2017). Frequently asked questions. Retrieved from http://www.wmo.int/pages/prog/wcp/ccl/faq/faq_doc_en.html

World Wildlife Foundation [WWF]. (2018). Half of plant and animal species at risk from climate change in world’s most important natural places. Retrieved from https://www.worldwildlife.org/press-releases/half-of-plant-and-animal-species-at-risk-from-climate-change-in-world-s-most-important-natural-places