4

Kimberly John; Matthew R. Harsh; and Eric B. Kennedy

Matthew R. Harsh, Assistant Professor, Centre for Engineering in Society, Concordia University

Eric B. Kennedy, Assistant Professor, Disaster and Emergency Management, York University

We cannot solve the sustainability challenges that we face today simply by generating more scientific information and advice and supplying it to decision-makers. Mitigating and adapting to climate change, managing natural resources, and responding to emerging public health needs typify the highly interdisciplinary contemporary issues that require decisive political and corporate action. In all these areas, reliable scientific expertise is needed to support decisions made by governments and industries – but it must be integrated in upstream, nuanced, contextually-appropriate, and relationship-driven ways to solve pressing sustainability problems (see, for instance, the emerging literature on the nuance of science advice including Hoffman, Ottersen, Baral, & Fafard, 2018). Furthermore, a ‘loading-dock’ approach – such as ‘dropping off’ semi-relevant science or having notable misalignments between researcher agendas and practitioner needs – is intrinsically problematic for the scientific community and often results in augmenting value-based controversies rather than solving underlying disagreements (Sarewitz, 2004; Sarewitz & Pielke, 2007). This reality means that there is a need for decision-makers who can straddle the boundaries between science and policy, including both scientists who can provide policy-relevant science and policy makers who are scientifically literate.

But, how can we best train science professionals to work across the science-policy interface? Many research institutions offer in-depth public policy degree programs such as Master of Public Administration (MPA) or specialized, graduate-level courses in policy for students who are training for careers in public service. However, these policy-oriented programs and courses are not always available to students in science, technology, engineering, and math-based (STEM) graduate programs and career tracks, and they do not often include specializations for those who want to focus on science policy and decision-making. Moreover, these opportunities rarely integrate neatly with the structure of STEM programs that focus on lab- or field-driven research while offering few opportunities for studying subjects outside of the specialty area. The academic job market compounds this problem. Science, technology, engineering, and math graduates are less and less likely to find careers in tenure-track roles and are more likely to work outside of academia in contexts which require an understanding of, and skills in, governance and administration.

In this chapter, we outline the role that public policy skills play in supporting sustainability, the growing impetus for graduate students in STEM to broaden their knowledge and experience in public policy, and the need for targeted public policy training for STEM graduates to support sustainability. We then introduce Science Outside the Lab (SOtL) North, an immersion program in science policy, and examine how it addresses the gaps and challenges of providing policy training to STEM graduate students in Canada.

Background

The need for STEM graduates to receive science policy training arises from today’s intractable sustainability challenges which require more than deep, technical expertise in economic, social, or environmental disciplines (Wallimann, 2013). The realm of policy encompasses how decisions are made, how values are incorporated, and how uncertainty is addressed, and scientific information is just one of several factors therein. Whatever forms they take in principle and practice, initiatives that respond to sustainability challenges need sophisticated policy development and support and effective implementation. This requires an “active and urgent process of policy learning” to facilitate the framing of policy and decision-making (Wilks-Heeg, 2015, p. 43).

Science graduates working on increasingly complex challenges, such as climate change or equitable public health systems, cannot assume that their research, once disseminated, will guide public policies. This is because the drivers and effects of sustainability issues transcend geographic boundaries and often span several local and global spheres of influence. Furthermore, as exemplified by climate change, sustainability issues include a multiplicity of social, environmental, and economic dimensions for which there are no integral, technological fixes – only highly contested issues and heterogeneous stakeholder communities. As a result, STEM graduates will need to participate as equal partners in the process of building sustainability in ways that foster and balance strong communities, economic productivity, and environmental ‘stewardship.’ They must understand policy processes, governance, and how to participate in policy making by working and communicating effectively with various stakeholders. Key knowledge and skills in public policy are summarized in Box 1 (Bergerson, 1991).

With less than 20% of Canadian post-bachelor graduates staying in academia (Lypka & Mota, 2017), there is also an oversupply challenge facing the traditional model of transitioning from doctoral research into tenure-track academic positions. Whether because of increased competition or increased demand in non-academic roles, the training of graduate students must increasingly incorporate the skills and competencies required for employment in government, business, and the nonprofit sector (Edge & Munro, 2015; Helm, Campa, & Moretto, 2012). Graduates in the fields of natural science, engineering, and health are even more likely to find employment outside of academic roles than their counterparts in the humanities, education, or social sciences (Edge & Munro, 2015). For these STEM graduates, their in-depth specialized knowledge and research and analytical and information management skills are highly prized by employers who are involved in the creation and implementation of public policy. For example, graduates with Ph.Ds. have the potential to facilitate the adoption of new evidence and the integration of academic research methods in areas as diverse as public health, technological management, and environmental governance.

However, there are gaps in post-graduate training that warrant the attention of graduate programs. In a 2-year investigation of graduate professional development programs at North American universities, the Council of Graduate Studies found that 8-11% of employers in the STEM workforce identified governance and science policy skills as being insufficiently addressed in the professional development of STEM graduates (Denecke, 2017). Edge and Munro (2015) also found that graduate students usually have strong networks and allies within academia, but they often need help building networks outside the academy. Therefore, the challenge is stark: sustainability requires new kinds of policy thinkers and decision-makers from an ever-growing (and potentially over-produced) cadre of graduate students. Yet, these students are often lacking the practical policy knowledge, networks, and skill development necessary to contribute their research talents to doing good outside of academia.

This generation of graduates is also launching their careers at a time when democratic norms are rapidly evolving, described by some as a “post-truth” era (Higgins, 2016). Both scientific information and misinformation are equally available and hyper-partisanship has reshaped public perceptions of science and experts. Society’s expectations of the roles of scientific and other realms of expertise are also changing and becoming polarized (Collins, 2014). Post-graduates who are preparing for careers in STEM are aware of how shifting public values and the changing roles of science in society call for enhanced approaches to sustainability. Many are interested in understanding how public policy decisions are made and how their research can better inform political decision-making and respond to policy (Science & Policy Exchange, 2016).

In addition to the drivers of both the demand for and supply of, science policy skills, Canada finds itself in a unique policy moment with respect to the role of science and evidence in decision-making. According to several public thinkers, the election of Justin Trudeau in 2015 represented an end of a period of contentious relationships between scientists and policy makers that had been present under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, a period sometimes called the “decade of darkness” (Greenwood, 2013; O’Hara, 2010). Having entered a time of less overt conflict, the scientific enterprise in Canada appears to be reinvigorated, improving the relationship with political decision-makers and cultivating the skills scientists need to work well at the interface of science and policy (Quirion, 2017).

Some intra- and inter-institutional initiatives have begun catering to the needs of STEM graduates who need training and exposure to public policy in Canada. For example, since 2008, the Ottawa-based Canadian Science and Policy Centre (CSPC) has provided a key venue for capacity building and networking among science policy leaders through the annual Canadian Science Policy Conference. According to the CSPC, more than 500 graduate students have gained experience at the intersection of science and society; joined policy discussions; and networked with senior scientists, provincial and federal science advisors, and policy makers through the CSPC conference (Canadian Science Policy Centre, 2018). As part of its thematic workshops before and after the conference, CSPC also offers an optional, short (2-3 hour) introduction to the basics of science policy. Since its initiation, the number of graduate students attending the annual CSPC conference has been steadily increasing. By 2017, graduate students and postdocs accounted for 22% of the 677 delegates at the conference, doubling both their numbers and proportion from 2016. Montréal’s student-led Science and Policy Exchange facilitates graduate students advocating for science-policy-relevant issues, exemplifying another example of STEM graduate’s growing interest in science policy learning (Science & Policy Exchange, 2018).

These factors – the demand for a new generation of leadership at the science-policy interface during a time of partisanship and growing distrust of experts, the need to help recent graduates transition into and become prepared for non-academic roles, and the enthusiasm within the country for building scientific capacity – led to the emergence of a leadership development program in Canada called Science Outside the Lab (SOtL) North.

Introduction to Science Outside the Lab (SOtL) North

Science Outside the Lab (SOtL) North is an extracurricular immersion program which offers graduate students from universities across Canada an intensive introduction to science and policy issues in Canada and direct exposure to the realm of governance. Science Outside the Lab North provides a diverse group of graduate students, post-doctoral researchers, and young professionals an opportunity to gain key knowledge and insights into the real world of policy making and the role of science in society.

Science Outside the Lab North ran its first program in 2016. It was developed by a small team comprised of authors Kennedy (York University, then at Arizona State University), Harsh (California Polytechnic State University, then at Concordia University), and Dr. Heather Douglas (Michigan State University, then at the University of Waterloo). From its inception, close partnerships were formed with both the University of Ottawa (specifically the Institute for Science, Society, and Policy, via its director Monica Gattinger) and the Centre for Engineering in Society at Concordia University for program space and logistics in Ottawa and Montréal, respectively.

Initially, support for the program came from generous contributions and donations, like administrative and financial support from Concordia University and the University of Waterloo, and from program fees paid by participants. In 2018, to make the program more sustainable in the long-term, Kennedy founded the Forum on Science, Policy, and Society (FSPS) as a Canadian federal not-for-profit organization to house SOtL North and other training initiatives at the science-policy interface. The not-for-profit provides administrative capacity for running the program and increased flexibility for efficiently using limited financial resources while allowing for the maintenance of strong partnerships with universities to access classroom space and support student recruitment efforts.

This Canadian program, SOtL North, was initially inspired by a program of the same name, run by Arizona State University’s Consortium for Science, Policy, and Outcomes (CSPO) in Washington, D.C., that started in 2007 (Bernstein, Reifschneider, Bennett, & Wetmore, 2017; Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes, 2018). The Canadian version of the program differs, however, in a number of respects. The American program recruits some of its cohorts from large US National Science Foundation-funded projects where principal investigators support the students because they see the benefits that providing training to members of their labs have on the ‘broader impacts” of science. Other US cohorts are associated with specific graduate programs, research networks, or policy themes. The Canadian program, on the other hand, currently runs a single, competitively selected admissions process across the country. The Canadian program is also slightly shorter (6.5 instructional days versus 10 instructional days in America), in large part to make the program more accessible to students with academic and employment obligations and to reduce the cost borne by students. Finally, as will be later discussed, the Canadian program emphasizes speaker participation from experts in all career stages (ranging from junior policy analysts to chief scientists) while the American program focuses on early-career speakers.

Program Structure

Science Outside the Lab North is an eight-day, intensive, in-person course split between Ottawa and Montréal. Participants interact directly with a wide spectrum of policy practitioners including government scientists, research funding agency officers, science-focused interest groups, science communicators, academics, and science advocates. Science Outside the Lab North organizers moderate the interactions using a modified version of the Chatham House rule (described later), which provides speaker anonymity and ensures that students receive authentic policy experiences from the guests.

Each SOtL North cohort consists of twelve to fifteen graduate students and junior researchers (at the Masters, Ph.D., and postdoctoral levels), as well as two faculty mentors who facilitate the program and live in residence with the program participants. The participants come from a variety of different countries. Past participants have come from Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States. During the first 36 hours, participants are introduced to the basic structures of provincial and federal governance and decision-making that affect science in Canada. Throughout the five days that follow, the participants learn directly from a wide range of invited decision-makers, ranging from junior policy analysts to provincial and agency chief scientists. Under the guidance of the faculty mentors, the participants lead informal, 90-minute, group interviews with guest speakers. These sessions begin with speakers giving very short overviews of their career trajectory and duties of their current job. They then proceed through a participant-led Q&A format that covers a broad range of topics including the policy making process, the science/policy interface, career opportunities outside of academia, and personal challenges in working on science-related topics in a political or public service setting. Speakers are discouraged from using PowerPoint or giving formal presentations so that the interaction can be driven by participants and focus on lived realities of science policy in Canada. These sessions often occur at the offices where speakers work so that participants can see the working environments and get to know the geography of science policy organizations in Ottawa and Montreal.

In addition to the sessions with decision-makers, interspersed throughout the program, participants engage in guided group reflection sessions where they are encouraged to examine their learning experiences. Additionally, SOtL participants informally meet with speakers and alumni from past programs at mixers, in Ottawa and Montréal, that facilitate more in-depth discussions and networking opportunities outside of the sessions.

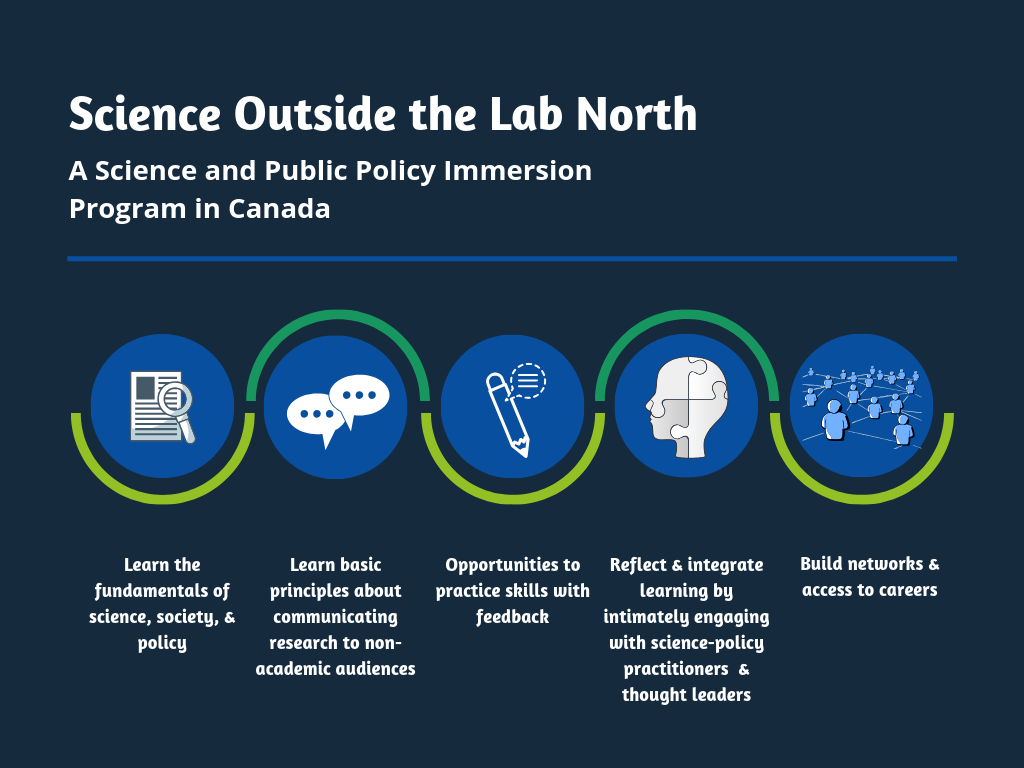

As a program, SOtL North has three primary pedagogical goals related to helping participants: 1) learn key knowledge about policy, 2) acquire skills related to real-world policy making, and 3) build networks and develop careers. In terms of skill development and knowledge acquisition, participants are (a) introduced to the basics of policy mechanisms and science policy and (b) taught basic principles about communicating their research to non-academic audiences and given opportunities to practice these skills with feedback. Key knowledge includes the relationship between Canadian ‘policy for science’ (i.e., the funding, directives, and goals for publicly funded scientific enterprise) and ‘science for policy’ (research geared to decision-making), the organization of government departments, and the theory and practice of the Canadian legislative process. There is also an explicit pedagogical focus on contextualizing these abilities to help students reflect on how real-world decision-making differs from textbook models as well as some of the limitations of science and how they can be accounted for in policy-relevant settings. The third goal, that of network development, includes facilitating connections between the participants and the roughly 15-20 visiting experts who participate in the program, helping the participants refine their networking skills and increase their confidence in building these connections. Exposure to the visiting experts also helps participants expand their sense of the opportunities to engage in policy, be it through continuing in academic roles, entering the public sector, quasi-research, advocacy, or activist organizations.

Overall, through SOtL North, students are asked to consider some of the more intractable challenges of working at the science-policy interface including the difficulty and complexity involved in developing science and technology policy; how these complexities impact relationships among science, engineering, and society; the roles of science and engineering expertise in science policy; and the limitations of scientific information in resolving values-based policy debates.

SOtL North’s Approach to Training Leaders

Since 2016, 67 graduate students and junior researchers have participated in SOtL North. These participants have come from universities across Canada and represented a wide range of both STEM (including medical sciences, natural sciences, and engineering) and non-STEM fields (such as social sciences, humanities, communications, and languages). In turn, the invited speakers have also come from different disciplines (food, health, defense, etc.), federal and provincial governments, and non-profits and industries, where they deal with politics and expertise in different ways.

For early to mid-career scientists, SOtL North serves to enhance their preparedness for work in sustainability at the interface of science and public policy. The program (see Figure 1) also helps meet the individual and societal needs for knowledge and awareness of governance processes, the reinforcement of leadership skills, and the creation of broader professional networks that would support STEM graduates’ careers outside of academia. The program begins with a one-day boot camp on the basics of policy and science policy in Canada. This is the only session that does not involve outside speakers since faculty mentors facilitate it. The session distills fundamental understanding about what science is and about basic civics – how the Canadian government is structured at the federal, provincial, territorial, and municipal levels – before introducing key interactions between science and policy in Canada.

Deep and nuanced awareness of science policy issues is built through unfiltered contact with diverse practitioners who funnel decades of experience into the participants. The critical leadership skills of self-directed learning, communication, and networking are strengthened as participants lead discussions with the speakers and many follow up with speakers after the program. Finally, in the debriefing session, participants synthesize what they have learned and provide critical and constructive feedback of the program’s effectiveness in meeting their needs. The qualitative and quantitative information that emerges from this session has been used to continuously refine the structure and content of SOtL North (see Harsh, Kennedy, Bernstein, & Reifschneider (2016) for a detailed description of program evaluation methods and results).

Former SOtL North participant and author Kimberly John described her experience in the program as a rare exposure to the technical, personal, professional, ethical, and political realities and trade-offs that science graduates and professionals face at different life stages. The program fostered integrated perspectives as participants and guests alike shared and examined information at the local, provincial, national, and global scales and charted their careers through various public and private institutions including academia, government agencies, think tanks, museums, funding agencies, consultancies, and non-profit groups.

Because of the complicated value trade-offs and complex institutional networks that characterize the science-policy interface, almost all of the speakers discussed how their career trajectories were non-linear and the unique mix of skills that supports their career. For example, one guest was a trained biologist who, after completing a Ph.D., found that in today’s political climate, they derived more value in advocating for science than in working as a pure scientist. Other guests spoke of the tensions between science advocacy and providing science advice in their everyday work. Some guests shared the struggle of maintaining one’s sense of identity as a scientist when no longer working closely with the scientific community, the challenge of navigating the public service’s rigid hierarchy, and the hard-won satisfaction of ushering scientifically sound trade deals or legislation through the Canadian Parliament.

At the end of SOtL North, there was a noticeable improvement in participants’ competence and confidence in communicating the relevance of their scientific work to various audiences, as seen in the evolution in how participants introduced themselves to speakers and the way they spoke about their research at the beginning of the program compared to the end of the program. However, simply communicating research may not be a priority training gap as many universities already offer science communication training for graduate students. As such, SOtL North is increasingly focusing on introducing participants to specific science-policy skills that are not addressed in their home institutions such as non-academic technical writing of memoranda, policy briefs, or op-eds. All the same, the program helped participants to identify the skills they would need and training opportunities for real-world policy development. More importantly, participants left the program significantly less convinced that scientific research is the most important factor in shaping policy (Harsh et al., 2016). This represents a major attitudinal shift and suggests the development of a more nuanced understanding of the relationship between science and policy.

Successes, Growth, and Challenges

As with any emerging educational program, SOtL North has had both success stories and issues that continue to need development. In the remainder of this chapter, we highlight four points of success, challenge, and reflection. The first point has largely been a success: building a trusted space for authentic dialogue between participants and visiting experts that has led to the emergence of a system of ‘SOtL House Rules.’ The next three points – increasing diversity among speakers and participants, scaling to meet demand, and placement and alumni networks – have included both success and challenges.

Trust and the ‘SOtL House Rules’

Because the program is so heavily focused on learning directly from experts in the field, it is crucial to be able to establish an environment of trust where all participants can be authentic, open, and honest. Lines of questioning can vary significantly, ranging from discussion of roles and responsibilities to detailed conversations about current issues and program roll-outs to very individualized and personal questions about achieving work/life balance or dealing with awkward or discriminatory situations in the workplace.

As such, trust is important throughout multiple timescales. During the session itself, establishing a culture of trust is crucial for obtaining authentic answers. This trust is also critical on a year-to-year basis, in terms of recruiting speakers to return and them recommending their colleagues to the program. This means achieving both qualitative feelings of trust and a dependable system to prevent participants from sharing sensitive information post-program. During the 2016 and 2017 versions of the program, SOtL North adopted the Chatham House Rule to meet these aims. In its original formulation, the Rule states that:

“When a meeting, or part thereof, is held under the Chatham House Rule, participants are free to use the information received, but neither the identity nor the affiliation of the speaker(s), nor that of any other participant, may be revealed” (Chatham House, 2019).

The modified ‘SOtL House Rule’ gives speakers an option for organizers to use their names in promoting the program and for participants to use their names after the program, as long as specific information relayed during the program is still not attributed to an individual or an organization. This has largely been deemed a successful modification to the Chatham House Rule based on the number of speakers who have been willing to participate in the program year after year.

Diversity

While the program has seen significant success in attracting participants from diverse disciplinarily backgrounds, there are other dimensions of diversity that remain more challenging to fulfill. Interestingly, both the applicant pools and selected cohorts (a blinded process) skew heavily female: only 22% of program participants have been male. Yet, other forms of diversity are more elusive. For instance. because of the disproportionate number of universities, program participants often lean heavily toward being Quebec and Ontario-based. More attention also needs to be given to recruiting from under-represented groups (especially Indigenous participants). More substantial program funding would also make a significant difference in supporting increased participation from those a greater distance from Ottawa and Montréal (those who face higher travel costs).

Similarly, the program has had a mix of successes and challenges in terms of the diversity of speakers. The program has been successful in recruiting a mix of male and female speakers and speakers that represent great diversity in terms of disciplinary training, area of work, sector of work (government, industry, and non-profit), and level of government. However, we have had more federal employees serve as speakers compared to industry and nonprofit sector speakers and more federal speakers compared to those working on policy at the international, provincial, and local levels. Recruiting a more racially diverse group of speakers also remains a challenge.

Science Outside the Lab North organizers are also developing ways of scaling to meet the demand for the program which now far exceeds participation. With the establishment of an alumni community (including a listserv, online community, and regional meet-ups), there are also increased opportunities for ongoing mentorship, networking, and training. The success of the alumni community has been significant, including alumni winning both the 2017 and 2018 CSPC Youth Science Policy Awards of Excellence. Science Outside the Lab North alumni have also been involved in the creation of a student science policy network at the University of Toronto and have had successful career placement into public service positions (such as the Natural Resources Canada recruitment program and the Government of Quebec foreign service). Also, author Kimberly John, is supporting the Trottier Institute for Science and Public Policy’s proposal for a Program Option in Public Policy at McGill University. This program option would be available to graduate students who want to understand how public policy works but are not enrolled in the Public Policy program.

Conclusion

We have shown that the current sustainability challenges and societal changes require improved approaches to integrating science into public policy. Science Outside the Lab North is a unique training program for STEM graduates across Canada that directly facilitates critical thinking about science, society, and public policy in the Canadian context. The program offers participants an opportunity to 1) learn and reflect on the fundamentals of science, society, and public policy while 2) intimately engaging with science-policy practitioners, thinkers, and real-world issues; and 3) developing their careers. This program addresses the needs and realities graduate students who have limited time and funding for full-blown courses and programs face yet provides depth and breadth for deep learning.

It would be easy to recommend the replication of SOtL’s approach to developing leaders in sustainability. However, any replication at the municipal, provincial, or national levels must consider the factors that have contributed to the program’s growth and effectiveness over the last few years. These factors include SOtL’s relatively low cost (due in part to the small, nimble organizing team) and short duration; the trust cultivated between instructors, guests, and participants through the SOtL House Rules, and the overall Canadian context where a (small) majority of the population holds science in high regard.

References

Bergerson, P. J. (1991). Teaching public policy: Theory, research, and practice. New York, NY: Greenwood Press.

Bernstein, M. J., Reifschneider, K., Bennett, I., & Wetmore, J. M. (2017). Science outside the lab: helping graduate students in science and engineering understand the complexities of science policy. Science and Engineering Ethics, 23(3), 861-882.

Canadian Science Policy Centre. (2017). CSPC 2017 Youth Science Policy Award of Excellence. Retrieved from https://sciencepolicy.ca/cspc-2017-science-policy-award-excellence-youth-category

Canadian Science Policy Centre. (2018). About the Canadian Science Policy Centre. Retrieved from https://sciencepolicy.ca/about

Collins, H. (2014). Are we all scientific experts now? Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

Consortium for Science, Policy & Outcomes. (2018). Science Outside the Lab. Retrieved from https://cspo.org/program/science-outside-the-lab/

Denecke, D., Feaster, K., & Stone, K. (2017). Professional development: Shaping effective programs for STEM graduate students. Retrieved from: https://cgsnet.org/ckfinder/userfiles/files/CGS_ProfDev_STEMGrads16_web.pdf

Edge, J., & Munro, D. (2015). Inside and outside the academy valuing and preparing PhDs for careers. Retrieved from: https://ucarecdn.com/630eb528-90d0-49c4-bfe9-5eacea7440b7/

Greenwood, C. (2013). Muzzling civil servants: A threat to democracy? Retrieved from: http://www.elc.uvic.ca/publications/muzzling-civil-servants-a-threat-to-democracy/

Harsh, M., Kennedy, E. B., Bernstein, M. J., & Reifschneider, K. (2016). Immersive policy education & Science Outside the Lab: Preparing scientists and engineers to guide technological development in transdisciplinary and cross-sectoral environments. Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Engineering Education for Sustainable Development. 284-391.

Helm, M., Campa III, H., & Moretto, K. (2012). Professional socialization for the Ph.D.: An exploration of career and professional development preparedness and readiness for Ph.D. candidates. The Journal of Faculty Development, 26(2), 5-23.

Higgins, K. (2016). Post-truth: A guide for the perplexed. Nature, 540(7631), 9. https://dx.doi.org/10.1038/540009a

Hoffman, S. J., Ottersen, T., Baral, P., & Fafard, P. (2018). Designing scientific advisory committees for a complex world. Global Challenges, 2(9), 1800075.

Lypka, C., & Mota, M. (2017). Graduate professional development: Towards a national strategy. Retrieved from http://www.ca.cags.ca/gdps/documents/Phase1_English.FINAL.pdf

O’Hara, K. (2010). Canada must free scientists to talk to journalists. Nature, 467(7315), 501-501.

Quirion, R. (2017). 10 tips for making researchers’ voices heard by politicians. Retrieved from: https://www.universityaffairs.ca/career-advice/career-advice-article/ten-tips-making-researchers-voices-heard-politicians/

Sarewitz, D. (2004). How science makes environmental controversies worse. Environmental Science and Policy, 7(5), 385-403. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2004.06.001

Sarewitz, D., & Pielke, R. A. (2007). The neglected heart of science policy: Reconciling supply of and demand for science. Environmental Science & Policy, 10(1), 5-16. https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2006.10.001

Science & Policy Exchange. (2016). Student perspective of STEM education in Canada: Strategies and solutions from an expert-led working group. Retrieved from: http://sp-exchange.ca/images/reports/Student%20perspective%20of%20STEM%20education%20in%20Canada%2C%20SPE%20white%20paper.pdf

Science & Policy Exchange. (2018). Science and policy exchange. Retrieved from http://www.sp-exchange.ca/about-us/

Wallimann, I. (2013). Environmental policy is social policy — social policy is environmental policy: Toward sustainability policy. Retrieved from: https://link.springer.com/openurl?genre=book&isbn=978-1-4614-6722-9

Wilks-Heeg, S. (2015). The challenge of sustainability: Linking politics, education and learning. In H. Atkinson & R. Wade (Eds.), The Politics of sustainability: Democracy and the limits of policy action. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/j.ctt1t894qh