21

Joseph M. Stokes and Chris D Craig

Introduction

An over-reliance on surface information and the inherent belief that education, in and of itself, results in a deeper understanding can limit our awareness of reality and our students’ relative success (Hattie, 2008). While memorizing and simplistic insights, or surface learning, are common in society, deep learning requires critical insights to extract meaning from experience (Warburton, 2003). Critical reflection is a cognitive and emotional activity or process associated with improved thinking and learning, but it requires active, careful, and persistent consideration (Rogers, 2001; Smith, 2011). Consider Brookfield’s (1987) four components of critical thinking as you reflect on your practice:

- identify and challenge your assumptions;

- recognize how situational context influences our thoughts and actions;

- consider alternative ways of thinking and teaching; and

- be aware of, but challenge, what experts consider the status quo.

As educators work to build and interpret meaningful curricula for their students, we must consider both the learning within the instructional setting and appropriate ways to reinforce core concepts. If teachers can’t critically challenge what they are doing in the classroom, it ultimately makes it hard to get better. Moreover, a focused evaluation of individual teaching practise can enhance content delivery methods, help us take responsibility for instructional design, and develop purposeful learning experiences (Brookfield, 2017).

This chapter will discuss the concept of critical reflection in education and how educators can use reflective practice to strengthen the consolidation of core learning outcomes within the instructional setting and long-range curriculum.

An Evolving Process

The early work of John Dewey and Donald Schön set the foundation for our current understanding of critical reflection, and engaging with their earlier work can help us contextualize our reflective practice (Farrell, 2012). Reflective practice can ensure that we have an increased awareness of our environment and that we as educators don’t stay on cruise control for too long, stuck in a repetitive cycle (Dewey, 1933).

Dewey (1933) connected reflective thinking to teaching by challenging educators to review what was happening in their learning environments and make adjustments based on the assessment of their observations. The idea may seem simple, and perhaps it’s a prominent part of modern teaching practice to some. But, Dewey’s ideas were unique for their time and started the discussions of how educators can move from routine teaching practices to a more intelligent and informed teaching practice. To help with our ability to be innovative and learn from challenging situations, getting comfortable with disruption is a good first step; we can then mentally restructure challenges as opportunities for growth. Breaking the routine is essential for ensuring good critical reflection, and it can augment teaching and learning in the classroom.

The later work of Donald Schön (1983, 1987) extended Dewey’s thinking, developing the concepts of reflection-on-action and reflection-in-action: the ability of an individual to be reflective in the moment and be actionable on that reflection. Schön (1987) connected the concepts to the idea of knowing-in-action, or the process of an individual’s awareness of their implicit knowledge. In the context of teaching, an educator can rely on their knowing-in-action, or their tacit knowledge, to help guide when reflection-in-action becomes necessary. When a teacher experiences situations outside the norm, Schön (1987) proposes that we move to reflection-in-action, which involves a critical evaluation and actionable outcomes.

Building on Schön’s work in the context of teachers, Farrell (2017) suggests many implications for real-time reflection in the teaching profession. Think about how many times we as educators have been in a situation in which our approach did not work. It is easy to bypass these situations, but they offer opportunities to engage in reflection that can enhance our teaching practice. If we as educators recognize these moments of reflection in action and act on them accordingly, we can refocus our attention and modify our teaching. And, at the very least, we might adjust our teaching to better respond to the circumstances and our learners.

Personal Practice

Some teachers today may be familiar with knowledge consolidation in the classroom. Consolidation exercises help reinforce key concepts in a summative fashion for teachers, reinforcing important information and allowing for clarification and exploration on the part of a student. One of the problems with knowledge consolidation exercises is that teachers may fall into the trap of assuming students’ understanding or perceiving one concept is more important to the class than another concept. In other words, teachers don’t know what they don’t know, and this is especially true of how educators can perceive the classroom environment. For example, it’s easy for an educator to believe that they are providing effective course materials, especially if they haven’t reflected on what they are providing. Critical reflection and good course consolidation meet when we gauge student understanding by asking them and assessing the responses. By building critically reflective consolidation exercises, teachers can create deep learning that is developed thoughtfully in the context of student needs.

Critical reflection in course consolidation can be a powerful tool for teachers who want to build solid lessons and a longer-range curriculum tailored to their students’ needs (Brookfield, 2017). The following general guidelines and activities illustrate how reflective practice can enhance knowledge consolidation activities in the physical or digital classroom.

General Guidelines

More recent work on critical reflection has built on earlier ideas and concepts. Brookfield (2017) recognized that critical reflection in the classroom needs to be an intentional process in which teachers continually evaluate and reevaluate the validity of their assumptions. The process can apply to various situations such as classroom dynamic and composition, content delivery tactics, and in-course activities.

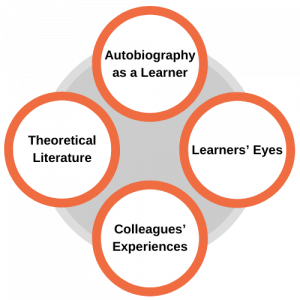

We, as educators, need to take the time to work the reflective process into our professional practice as the intentionality of the reflective process is critical for success. While it may be easy to recommend that teachers become reflective practitioners (Schön, 1987), we concur that the tactical approach of incorporating critical reflection is challenging. Most teachers would likely feel that they reflect on their teaching at some point in their day, but there are some interesting and practical ways to be truly intentional about the process. We suggest Brookfield’s (1998) Lenses (Figure 1) as a concise framework and offer further opportunities in the activities section following.

Figure 1.

Brookfield’s (1998) Lenses

Lens 1: Our Autobiography as a Learner of Practice

Reflecting on our learning history can add context to what we feel strongly about and why we gravitate towards it, casting light onto something we consider instinctual. The process can help us understand personal biases along with strengths.

Lens 2: Our Learners’ Eyes

Understanding how our students perceive us and our teaching practices can be surprising. Interpretations can be diverse and guide insight into how personal backgrounds shape individual learning. While live student conversations can offer some insight, blinded feedback is critical for enhanced honesty.

Lens 3: Our Colleagues’ Experiences

Conversations with our colleagues can help us reflect on and broaden our perspectives on experiences and practice. Further, diverse perspectives (ex. talk with a physical sciences and arts educator about the same topic) can also help build awareness, and a feeling of connection, recognizing our experience might not be unique.

Lens 4: Theoretical Literature

Considering and reflecting on the theory and psychology underpinning our learning approach helps us understand strengths and gaps in our practices. The resulting understanding can help us recognize weaknesses and stimulate a process to help address such a gap.

Potential Limitations or Issues

- Reflection can recall profound experiences that might not always be comfortable (Brookfield, 1998).

- Students may find blatant honesty challenging, even in anonymous situations, and might fear reprisal if the educators’ feedback might not be considered desirable (Brookfield, 1998).

- Critical reflection might not be immediately rewarding (Watson & Kenny, 2014).

- Vague or limited reflection may relate to superficial learning (Ash, 2004).

- We might not always like what we hear or receive.

- Seeking peer insights from like-minded individuals may enhance bias and inhibit personal growth.

Activities

Activity 1: Reflective Journaling

Overview

Reflection journaling can be helpful as teachers become more actively reflective of their practice in the classroom. A recent study by Zulfiker and Mujiburrahman (2018) found that teachers perceived an increase in their overall performance when engaging in reflective journal writing. Journaling can be easily facilitated in our digital world through blogs, websites, or other digital tools that allow for reflective process (Cheng et al., 2015). Also, the process can be private or shared with peers and students, depending on intent.

Description

- Limit friction by considering a platform you are motivated to learn about or find easy to use. Ensuring ease can help build the habit of reflecting (Fogg, 2019).

- Schedule a time or trigger activity to enhance active engagement following existing life patterns (Fogg, 2019). An example for scheduling a time could be inputting journaling into your digital calendar as an event, while a trigger could be journaling while you drink your morning [insert beverage of your choice here].

- Manage expectations. Clearly outline manageable expectations for what you need to achieve each time you create a reflection, so there is no reason that you can’t engage in the reflection process (Fogg, 2019). Examples include one paragraph, five bullet points, or five minutes.

Possible Challenges

- It’s easy to forget a commitment to ourselves when concerned about others and their learning outcomes.

- Consistency. Some form of consistency is paramount for developing insights over time.

- Tech changes. Digital technology and our access to it can change over time.

Resources

- 14 Reasons Teachers Should Keep a Reflective Journal

- Use of Reflective Journals in Development of Teachers’ Leadership and Teaching Skills*[PDF]

Activity 2: Learner Critical Reflection Questionnaire

Overview

By using a Forms platform that easily integrates with the learning environment, an educator can develop a class reflection log that affords for blinded and meaningful reflection on class activities. The resulting record can guide an understanding of student challenges, experiences, and perceptions for immediate and future reflection.

Description

Consider what information you would like to reflect on, and develop consistent questions throughout the course. Inspired by Brookfield’s (1989) Classroom Critical Incident Questionnaire, we offer the following sample questions:

- At what moment in our session today did you feel most engaged?

- At what moment in our session today did you feel least engaged?

- What event did you find the most affirming or helpful?

- What event or insight surprised you the most during the session?

Guidelines

- Be concise, making the intent clear but open for interpretation.

- Anonymize or blind the feedback process to enhance honesty and avoid embarrassment.

- Repeat the questions throughout the term to provide consistent landmarks for student reflection. The repetition reduces your time requirements and may increase students’ comfort as they know what is coming.

- Limit questions. Use a limited number of questions, three to five, to reduce perceived overload.

- Give time in the class. The built-in time is already in student schedules, requiring little extra effort on their part (= greater chance of participation).

- Review insights by linking a linked spreadsheet to collect responses for personal reflection. The spreadsheet also affords chunking by date, formatting, and filtering particular insights.

Possible Challenges

- Honest feedback. Students might be nervous about providing honest feedback for fear of reprisal, even in an anonymized process.

- Blinding presents challenges related to consistency as we cannot narrow evolving individual student perceptions or even determine if the same students are responding.

- Students might have limited motivation to engage and respond.

Resources

- Critical Incident Questionnaire — Stephen D. Brookfield

- Full article: Using student feedback to improve teaching

- Improving practice through student feedback

Activity 3: Connect on Social Media

Overview

Using social media can help educators with the reflective process (Brookfield, 2017), as we can use online platforms to connect with their peers and students to achieve desired outcomes. We can communicate on specific topics and connect with people outside our traditional circle of influence by connecting with online peers. With students, we can communicate in an environment that they are often used to, offering unique opportunities to understand student comprehension and attitudes toward course material. Also, we can engage in or foster collaborative experiences that standard education technologies might not afford.

Description

- Consider the primary intent and purpose of using social media. We can consider demographics (e.g., students or peers), desired outcomes, and time-related actions or activities.

- Pick a platform that aligns with your intent (e.g., Twitter is often associated with textual content, Instagram is primarily image-based, and Facebook skews to an older demographic).

- Review institutional or departmental guidelines regarding branding, sharing, and privacy.

- Develop a personal plan for the critical reflection of the experiences and how they impact your practice.

Possible Challenges

- International peers or students may have limitations related to specific platforms.

- We extend our presence beyond the traditional confines of the institution.

- Digital technologies can be fashionable, and their reach may change with time (consider the story of MySpace as a case study).

- We may require time to learn about platform function, reach, and privacy.

Resources

- Social Media for Teachers: Guides, Resources, and Ideas | Edutopia

- Educator’s Guide to Social Media – ConnectSafely

- Social Media for Educators: Strategies and Best Practices [Book]

- Social Media in Education: Resource Toolkit | Edutopia

Activity 4: Consolidation Through Design Thinking

Overview

While the process of critical reflection is informative, it requires implementation. Building on the concept of design thinking, we offer a framework to implement the insight(s) gained from critical reflection. Design thinking can guide the development and implementation of new ideas through a context-dependent framework (Black et al., 2019; Leifer & Meinel, 2016). Building on the Stanford model (Plattner et al., 2011), we offer a framework for consolidating insights.

Description

- Critically reflect on your practice from insights you’ve gained through activities one-three (or from your personal process).

- Define what you plan to implement. In this stage, create a concise and communicable issue that you plan to address.

- Ideate (idea generation) different strategies that you could implement to address the issue. Examples include mind maps, collaborative discussion, and the 5 W’s (who, what, where, why, when, how). Try not to limit yourself in this stage; create as many ideas as possible.

- Prototype your solution(s). You start to expand on a particular idea and create a skeleton of your solution in this stage. Consider your students at this stage, building on your reflection to see if the concept can enhance your desired outcome.

- Test your prototype to gain insights into its effectiveness. You may elect to let it sit for a time to approach it with a fresh focus, ask your colleagues for feedback, do a trial with a small group, or even implement it live in a course.

- Critically reflect on how your idea was received, start the process again if required, or move on to the next task.

Possible Challenges

- The timing might be challenging. Depending on your approach and experience, the design thinking process can take time.

- Students change, and what might work for one group may not work for another.

- If our new idea isn’t successful, we might experience disruptive emotions that challenge our desire to adapt.

Resources

- Design Thinking in Education | HGSE Teaching and Learning Lab

- An Introduction to Design Thinking PROCESS GUIDE [PDF]

- The world is poorly designed. But copying nature helps [6:49].

- Abstract: The Art of Design | Tinker Hatfield: Footwear Design | FULL EPISODE | Netflix [41:46]

- Tools for taking action. — Stanford d.school

General Resources

- Keynote: Assessing Our Impact on Students’ Learning: Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher

- Becoming a Critically Reflective Teacher, 2nd Edition | Wiley

- Reflecting on Reflection: A Habit of Mind | Edutopia

References

Ash, S. L., & Clayton, P. H. (2004). The articulated learning: An approach to guided reflection and assessment. Innovative Higher Education, 29(2), 137–154. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:IHIE.0000048795.84634.4a

Black, S., Gardner, D. G., Pierce, J. L., & Steers, R. (2019). Design thinking. In, Organizational behavior. OpenStax. https://opentextbc.ca/organizationalbehavioropenstax/

Brookfield, S. D. (1987). Developing critical thinkers: Challenging adults to explore alternative ways of thinking and acting. Jossey-Bass.

Brookfield, S. D. (1998). Critically reflective practice. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 18(4), 197-205. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.1340180402

Brookfield, S. D. (2017). Becoming a critically reflective teacher. John Wiley & Sons.

Cheng, M., Pringle Barnes, G., Edwards, C., Valyrakis, M., & Corduneanu, R. (2015). Transition skills and strategies-critical self-reflection. The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. https://www.enhancementthemes.ac.uk/docs/ethemes/student-transitions/critical-self-reflection.pdf

Farrell, T. S. (2012). Reflecting on reflective practice: (Re) visiting Dewey and Schon. Tesol Journal, 3(1), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.10

Fogg, B. J. (2019). Tiny habits: The small changes that change everything. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Hattie, J. (2008). Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

Leifer L., Meinel C. (2016) Manifesto: Design thinking becomes foundational. In H. Plattner, C. Meinel, & L. Leifer (Eds.), Design thinking research. Understanding innovation (pp. 1-4) Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19641-1_1

Plattner, H., Meinel, C., & Leifer, L. [Eds.]. (2011). Design thinking: Understand – improve – apply. Springer.

Rogers, R. R. (2001). Reflection in higher education: A concept analysis. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1), 37–57. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010986404527

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Towards a new design for teaching and learning in the profession. Jossey-Bass.

Smith, E. (2011). Teaching critical reflection. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(2), 211–223. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.515022

Warburton, K. (2003). Deep learning and education for sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 4(1), 44-56. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370310455332

Watson, G. P. L., & Kenny, N. (2014). Teaching critical reflection to graduate students. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 7(1), 56-61. https://doi.org/10.22329/celt.v7i1.3966

Zulfikar, T., & Mujiburrahman. (2018). Understanding own teaching: becoming reflective teachers through reflective journals. Reflective Practice, 19(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2017.1295933