Working with Information

Rowena McGregor and Robyn Tweedale

Introduction

Working effectively with information is key to successful study and research. The effective and ethical use of information, and especially scholarly information will form the basis for writing essays, assignments, reports and examinations, and constructing visual and oral presentations. It is important to learn how to find information that ‘matters’ and why it matters. Information and information literacy will provide a link between your life experiences as a student, the wider academic world of scholarship, and the post-academic, real world, and professional applications of learning.

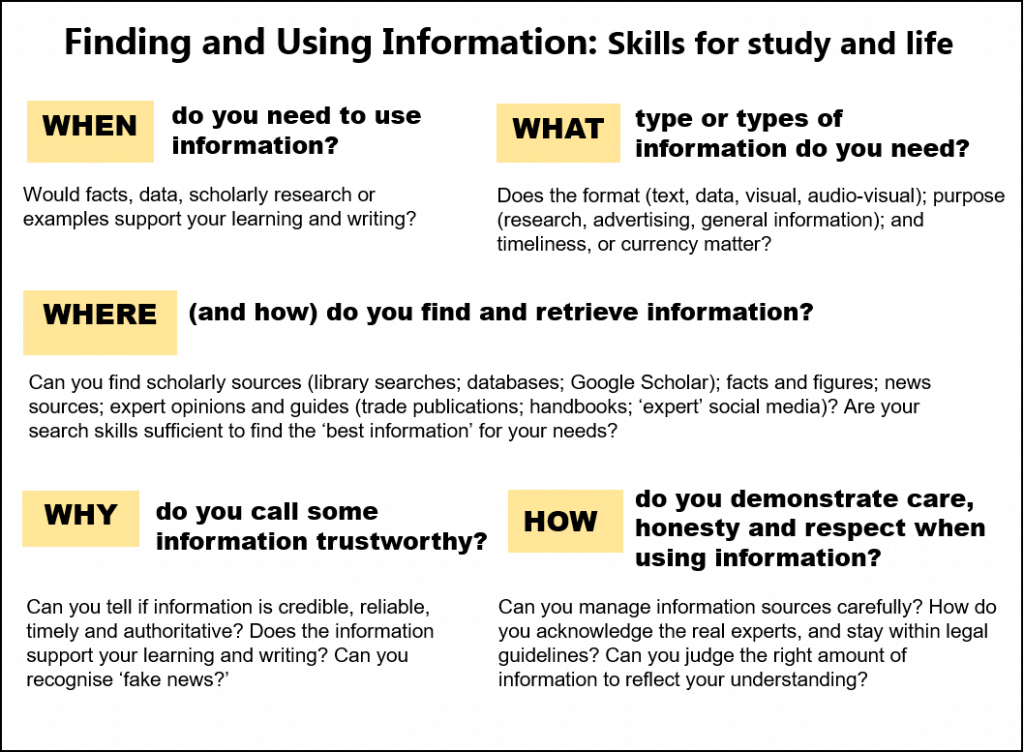

This chapter will help you develop your Information Literacy, or the knowledge, skills, and understanding underpinning the when, what, where, why, and how of finding, using, and referring to information. As an information-literate person, you will be able to:

- Understand your information needs (When do I need information? What type(s) of information do I need?)

- Determine where information is kept (Where is the best place to find this? Where should I search for the information?)

- Develop the skills to find the information where it is stored (What tools are available to help me find the information? How do I use these tools?)

- Evaluate information, to identify the ‘right’ kind of information, and discard the non-useful or irrelevant information (Why is this information useful? Why do I trust this source of information?)

- Record, manage, and reference information effectively (How will I use the information? How will I reference the source?)

Figure 5.2 outlines the importance of information and information skills for study and for life.

While working with information, it will be helpful if you are willing to develop critical thinking or questioning. This critical approach is the core of developing critical information literacy skills, not just during academic study, but for the rest of your life. Please see the chapter Thinking for more discussion on critical thinking.

What is information?

Information takes many forms. We tend to think of information as being published in books, journals, magazines and newspapers. However, there are many other types of information – pictures, photographs, videos, cartoons, podcasts, tweets, social media posts, web pages, blog posts, and… the list is endless. Not all information is written text, and not all information is ‘officially’ published.

It is important to note, however, that all information is considered the property of the owner or publisher, whether it is your course textbook, a blog post you found on Google, or a cartoon you found in Pinterest. Therefore, academic integrity, or the honest, respectful, and ethical use of information sources applies equally to all information.

While you are studying, you may need to draw on many different types of information, depending on what you are creating, and how you will use it. Your lecturers will expect you to find relevant information sources, but they will also expect you to be careful and discerning to avoid ‘fake’ or invalid information in an academic context. It is important to recognise not only what types of information sources are, but also which ones are most appropriate for your needs. Following are some information types you will use in the university environment.

Scholarly information

Scholarly information is written by qualified experts (often academics) within a university setting for scholars in a particular field of study. The author is identified, and credentials are available. Sources are documented, and technical language is often used. Understanding this language requires some prior experience with the topic. Attending your lectures and tutorials and completing any assigned readings will help you to develop this understanding. Scholarly information has many forms. These forms include:

Books

Also known as a monograph, scholarly monograph, research monograph, or scholarly book, a book is written by one or more authors and published by a scholarly publisher. The book will discuss a specific topic and even if it was written by a small team, it will read as one cohesive text.

What about textbooks?

Strictly speaking, a textbook is a scholarly publication. However, textbooks tend to give a broad, general, and introductory overview of a topic rather than the specific information you will need to respond to your assessment tasks. It is best to use your textbooks to develop your understanding and familiarity with the discipline-specific language, and use and cite other forms of scholarly literature in your work.

Book chapter

Also known as a scholarly chapter, or scholarly book chapter, a book chapter appears in a book edited and written by many academics. A book chapter is a discrete entity. This means that although the book will discuss a shared topic, the chapters may present conflicting arguments and perspectives on that topic within the same book.

Peer-reviewed journal article

Also known as a peer-reviewed article, scholarly article, or research article, a peer-reviewed journal article is rigorously reviewed by one or more academics before publication. The review process ensures published articles are factually accurate, report scientifically validated results, and that biases or limitations are noted in the text. For these reasons, peer-reviewed articles are highly regarded by academics. You may sometimes be required to refer to peer-reviewed articles only when writing an assignment. There are two variants of peer-reviewed journal article.

Empirical article

Sometimes referred to as a primary article, an empirical article is a peer-reviewed journal article that reports the finding of a research project.

Literature Review

The literature review is a peer-reviewed journal article that collates and reports on the research in the field. Some literature reviews attempt to include all of the relevant research that addresses a specific question or area of interest. These literature reviews are called: systematic reviews or systematic literature reviews.

Conference paper

Conference papers may be presented at academic or professional conferences. Although some conference papers are reviewed, the process is rarely as rigorous as that required for peer-reviewed journal articles.

Tip: If you find a relevant conference paper, check whether the authors also published the results in a peer-reviewed journal, as an article will generally be viewed by your markers as being more credible than a conference paper.

Note: However, in fast changing disciplines such as Information and Communication Technology, conferences are highly regarded as the time taken to publish other forms of scholarly information may make them obsolete before they are available to read.

Professional information

Professional information sources are written for professionals in a field. The author is most often identified, however, sources are not always documented by citations and a reference list. The language may or may not be technical. A trade magazine is a professional information source.

Popular literature

Popular information sources communicate a broad range of information to the general public. The author is often not identified and may not be an expert. Sources are often undocumented. It is therefore difficult to assess whether a popular source is reliable. The language used is not technical. Popular information may also be commercial; aimed at selling something (advertising) or persuading to a viewpoint (political or propaganda). Examples of popular information sources include news reports, social media posts, and websites.

Grey literature, also gray literature

Grey literature is authoritative information, often published by government bodies and non-government organisations (NGOs). Grey literature is usually published and made available on an organisation’s website. The authors may be individual experts or a panel or committee. Reports, including research reports, literature reviews (not published elsewhere in a journal), policy documents, and standards are common forms of grey literature.

Primary sources

A primary source provides information collected and reported verbatim. Primary sources are often discipline-specific. In Law, primary sources include court reports and legislation. Historians may work with ancient texts. Sociologists may study policy documents. Social scientists in all disciplines often work with interview recordings and transcripts. Other scientists work with raw data and statistics collected in the field, such as weather recordings, or from national repositories: population statistics. A primary source is usually analysed, critiqued, or directly discussed in your work.

Finding print and online information resources

You will need to find a variety of information to complete your study and assessment tasks. It is tempting to read a task and immediately dive into searching. However, a strategic approach will save time and enable you to access the highest quality resources in your discipline. Clarifying the content you are looking for, the appropriate genre/format/type of information for the task, and the best place to look for this information will inform and power your search.

Identify what you need

Before you search, read an assignment task or question carefully. Take note of or highlight all words that indicate the topic of your search. These words will form the beginning of your list of keywords. Also note any instructions around the type of information recommended – or required – to complete the search. This may be general (e.g., scholarly sources) or specific (e.g., peer-reviewed journal articles published within the last five years). If you are unsure of any of the terms used to describe what you need to find, ask your tutor or relevant course contact person before you begin your search.

Identify where to search

Knowing what you are looking for will help you to decide where to search. Scholarly information, grey literature and primary sources are located in a variety of online collections and sites. Some of the places you can find these information sources are provided below.

Searching for scholarly information

Scholarly information is best found via a library search, a direct search of your university database, or via use of the search tool: Google Scholar. Library search and database searches have several advantages. These advantages are:

- Subscriptions to journals and other electronic items allow you to access and download most of the information you discover

- Powerful filters and tools to focus your search and reduce the number of unwanted materials in the search results

Google Scholar, a Google tool that returns scholarly information, certainly has a place in your search strategy. Google Scholar will give an indication of what has been published on a topic. It can also be used to find additional keywords and phrases for your searches. Google Scholar can also be linked to your university library so you can directly access the resources available to you via your library subscription.

Note: Scholarly information is the most often required information for university study, therefore, the search techniques described later will focus on finding and retrieving scholarly information.

Searching for grey literature

Your library will likely have databases holding grey literature. These databases can usually be found by using the same techniques used to search for scholarly information. However, some specialist information is best accessed online via a Google Advanced search.

The Google Advanced search tool allows you to focus your search and restrict it to specific domains or websites. It is a two-part online search form. The top part of the form allows you to construct a search. Look carefully at the descriptors to each side of the various search boxes to create the most effective search. The bottom half of a Google Advanced search allows you to restrict your search by language, geographical region, date of last update, and via site or domain to search a specific website or for a publication available only on government websites. Please speak to a librarian for guidance on searching for grey literature.

Searching for primary sources

Primary sources are found in different places, according to genre/format/type of resource. Please speak to a librarian for guidance on searching for primary sources.

Newspapers

- Current and recent newspaper articles may be available via electronic databases from your university or national library

- Older newspaper articles may be available via national repositories provided by your national library. For instance, Australian newspapers can be accessed in the ‘TROVE’ collection.

Legal sources: Legislation and law

-

Figure 5.6 Legislation and law reports are primary sources. Image by cottonbro used under CC0 license. Legal databases are provided by all university law libraries

- National and international legislation and laws can be found on the World Legal Information Institute (WorldLII) website

- Australia Legislation and law can be accessed on the Australasian Legal Information Institute (AustLII) website.

- The laws of your country, state, or territory are also available online on Court and Government websites

Data and statistics

- Discipline-specific databases, provided by your library are a good source of statistics

- ‘World Statistics’: free and easy access to data provided by International Organisations, such as the World Bank, the United Nations and Eurostat

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) provides official statistics on economic, social, population and environmental matters of importance to Australia

Search strategies

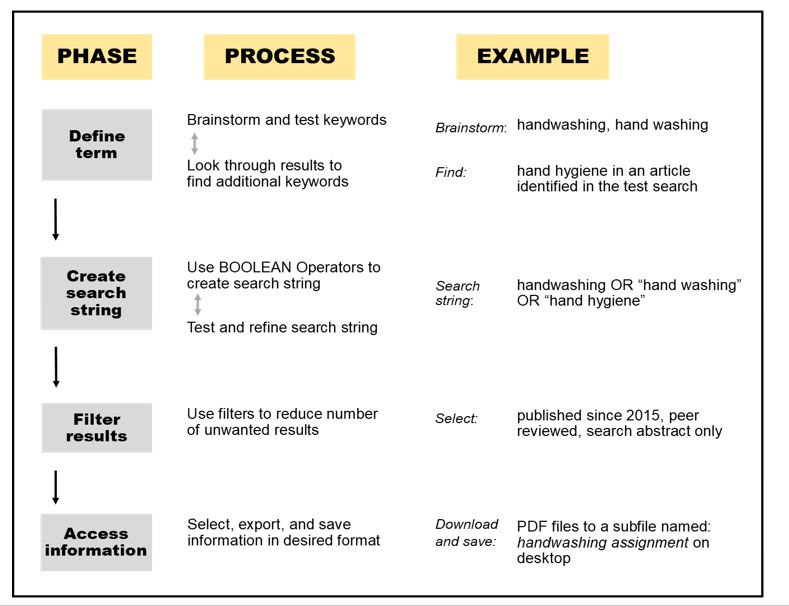

The search techniques described here focus on finding and retrieving scholarly information. Once you have established what you are looking for and where to look, you are ready to create a search. Your goal now is to locate the information you need while keeping the number of irrelevant results to a minimum. To achieve this, you will need to create a list of keywords and combine these appropriately for your search. You will then apply filters to discard many irrelevant results. The final task is to export and save the resources you identify as being most suitable for your need. Some of the steps may need to be repeated as you develop your search strategy. Figure 5.7: Search flow chart illustrates the steps. A more detailed description of the steps follows.

The first step is to define your terms. First look carefully at your task and highlight the content words – the words that describe the topic. Then brainstorm to create a list of all the synonyms, similar words and phrases that you think may be used to describe the topic in the scholarly literature. Test your list by searching in library search, a database, or Google Scholar. Add any additional words and phrases you discover to your list. In the example provided in Figure 5.7, I added the phrase “hand hygiene” as I saw this in an article retrieved in a test search. You may need to remove words bringing unwanted results. Keep track of your work in a table or list to avoid wasting time by repeating failed searches or losing effective searches.

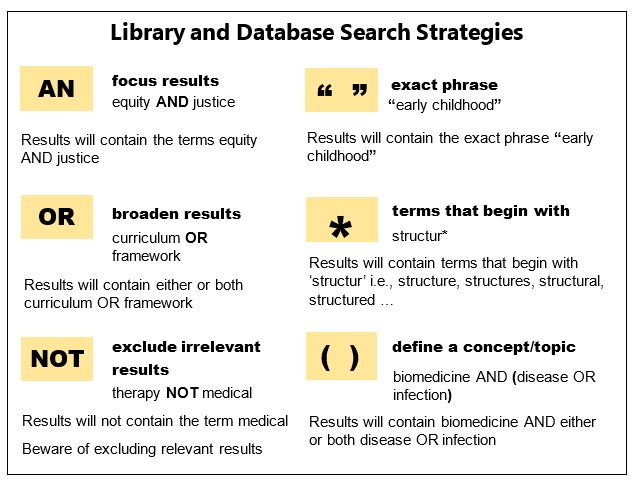

The second step is to create a ‘search string.’ A search string lists the keywords in a way the databases or other resources you are searching will be able to ‘understand.’ Library search and most scholarly databases require you use language in a precise way. Figure 5.8: Library and database search strategies explains this in detail.

Note: Library search and most databases do not understand natural language, so we need to use a logical framework to structure the search. All letters in the words AND, OR, and NOT must be capitalised or they will often be ignored or replaced with ‘AND.’ Exact phrases must be contained in double quotation marks. To find all associated words starting with the same ‘root’ add an asterisk after the root of the word. Finally, to search for a list of likely words, place the list within parentheses and separate them with OR. Test your search string and make any additions – or remove items – until you are satisfied that your search has captured the relevant resources.

The third step is to use filters to refine your search and remove unwanted results. Filters are a list of options you can select to remove results that are not suitable for your purpose. Filters vary according to the database but often include publication date, type of resource, and whether the resources are peer-reviewed. Filters are located to the left of the screen in most databases.

The fourth and final step is to access the information. Library search and databases will have a few options for exporting your search results. Select one or more items from the list and either save the list to your computer or email the list to yourself. A saved list is useful should you wish to retrieve the documents at a later time or collect the details you need for referencing from the list.

When you are ready to download and read the information you have retrieved, look for a PDF icon. Where available, the PDF will be the official version of the article, book, or book chapter. It will have the correct pagination and publication details (required for referencing) and will be the fully edited and finished version of the work.

Evaluating information

The American Library Association notes the need to “recognise when information is needed and have the ability to locate, evaluate, and use effectively the needed information” (Association of College and Research Libraries, 1989). We need information almost all the time, and with practise, you’ll become more and more efficient at knowing where to look for answers on certain topics. As information is increasingly available in multiple formats, not only in print and online versions but also through audio and visual means, users of this information must employ critical thinking skills to sift through it all.

You likely know how to find some sources when you conduct research. And remember—we think and research all the time, not just in school or on the job. If you’re out with friends and someone asks where to find the best Italian food, someone will probably consult a phone app to present choices. This quick phone search may suffice to provide an address, hours, and possibly even menu choices, but you’ll have to dig more deeply if you want to evaluate the restaurant by finding reviews, negative press, or personal testimonies.

Why is it important to verify sources? The words we write (or speak) and the sources we use to back up our ideas need to be true and honest, or we would not have any basis for distinguishing facts from opinions that may be, at the least damaging level, only uninformed musings but, at the worst level, intentionally misleading and distorted versions of the truth. Maintaining a strict adherence to verifiable facts is a hallmark of a strong thinker.

Many universities may use some kind of framework to help you evaluate the information you use. These frameworks focus on evaluation techniques and strategies, such as:

- The credibility or credentials of the author, and whether they are an expert on the topic;

- Looking for biases on why or how the information was published, for persuasive or propaganda purposes;

- The validity and reliability of the publisher, and how information is presented and packaged;

- The timeliness of the information, or whether it is still regarded as current; and

- The reliance on verifiable facts and evidence to support any claims or statistics.

This type of framework is a good place to start, especially when thinking about traditional published sources such as books, e-books, journal articles, and resources from library databases. Two examples of these frameworks are called C.R.A.A.P. (Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose) and R.E.V.I.E.W. (Relevance, Expertise, Viewpoint, Intended audience, Evidence and When published).

Although these frameworks provide you with a way to think carefully and evaluate information, they are not perfect, especially for web-based information sources which operate on different rules from traditional published sources (Wineburg et al., 2020). As Johnson (2018, p. 35) states “No universal formula or checklist can replace the critical thinking needed to determine if information is credible, but checklists and formulas can be a starting point for many students”. You probably see information presented as fact on social media daily, but as a critical thinker, you must practise validating facts, especially if something you see or read in a post conveniently fits your perception. It is important to remember that the internet is also renowned for spreading rumors, fake news and scams. Digital misinformation has even been recognised as a threat to society (Del Vicario et al., 2016). Be diligent in your critical thinking to avoid misinformation!

An example of a contentious information source at university is Wikipedia. Wikipedia is a source that many of us use every week for quick and simple information. However, most lecturers will not appreciate if you rely on Wikipedia for your research, and some may even explicitly forbid it. Why? Wikipedia is widely regarded as being of questionable reliability, because it is a freely available source to which anyone can contribute and the authors cannot be identified (Angell & Tewell, 2017). So any facts presented in Wikipedia need to be explicitly verified in other sources before you can rely on them for academic research. In general, it may be better to rely on other sources for your academic research. A professional, government, or academic organisation that does not sell items related to the topic and provides its ethics policy for review is worthy of more consideration and research. This level of critical thinking and examined consideration is the only way to ensure you have all the information you need to make decisions.

Other social media and news sources can be equally unreliable. We have all heard of ‘fake news’. When someone publishes an opinion or rumor, a lot of people will read it, and may even believe it without evidence. People tend to rely more on information that reinforces their own beliefs, values and opinions, and will tend to form communities with like-minded others (Del Vicario et al., 2016). This may cause a phenomenon known as ‘confirmation bias’, where people will look for this information to bolster their own perceptions and ignore any information that may discredit them. Part of critical thinking is striving to be objective and this is very important when it comes to recognising digital misinformation.

Some more strategies to help you evaluate web-based and digital information include:

- Who is responsible for the site (i.e., who is the author)? Look up the author, and see if they have written anything else and if there are any obvious biases present in that writing. Is the topic within the expertise of the person offering the information?

- Where does the site’s information come from (e.g., opinions, facts, documents, quotes, excerpts)? What are the key concepts, issues, and ‘facts’ on the site?

- Can the key elements of the site be verified by another site or source? In other words, if you want to find some information online, you shouldn’t just Google the topic and then depend on the first website that pops up.

- Can you find evidence that disputes what you are reading? If so, use this information. It is always useful to mention opposing ideas, and it may even strengthen your argument.

- Take into account the funding behind a website. You can check the ‘About’ section of a website, but remember that this is written by the people who are responsible for the website, so it may be somewhat biased.

- You may choose to trust information more when it is published on a government (.gov) or academic (.edu/.ac) website, but be careful about commercial (.com/.co) and non-profit (.org) websites, since these are mostly unregulated.

Managing information and resources

Once you have constructed a search and retrieved the appropriate and relevant information, you will want to manage the information so that it is easy to find, access and retrieve whenever you may need it. If you don’t keep records of the information sources you find and use, it can be very difficult to find them again. At a minimum, you will need to record the referencing details and links to digital information. It is also important to manage a backup system, either on the cloud, or separate physical storage, so you don’t lose all your own hard work.

Academic integrity

In the context of working with information, academic integrity refers to the honest, respectful, and ethical use of information sources in your assignment. You must be honest and indicate where and how often you used information created by others. You must be respectful of the work of others and communicate these ideas correctly. You must be ethical and not claim the work of others as your own, or present work that is merely a list of what others have said on the topic with no added critical or intellectual work of your own. Academic integrity is demonstrated by the accurate attribution of any ideas, direct and indirect quotes, images, or other information you used in your work to the correct information source. Directions on how to attribute correctly are provided by the referencing style guide (or guides) recommended by your university.

Referencing

Referencing is the consistent and structured attribution of all ideas, words, images, statistics, and other information to the source. There are thousands of referencing styles, most falling within the author-date or numbered families. Check your university website for guidance on the style to use and how to reference in that style. Following is a description of the two referencing ‘families.’

Author-date referencing styles

In these styles, the name of the author (or authors) and the year of publication must be provided as an in-text citation whenever you use someone’s words, ideas, images, or other works. Often this means several sentences within a paragraph will contain an in-text citation. The author name and date may be written as part of the sentence, for example: ‘Wang (2017) discovered…’ In-text citations can also be provided in brackets at the end of the sentence. This may look like ‘… (Wang, 2017).’

Author-date styles also include a reference list, usually on a separate page at the end of the assessment. The reference list contains everything mentioned as an in-text citation – and nothing else. Each entry in the reference list provides the name of the author/s or creator/s, the date of publication, the title of the work and where it was produced or available online. APA and Harvard are author-date referencing styles.

Numbered referencing styles

Numbered referencing styles require a number in each sentence where someone’s words, ideas, images, or other works have been used. The details of the work – names, dates, title, and location – are provided in footnotes (listed in numerical order at the bottom of every page) or endnotes (listed in numerical order at the end of your work). AGLC and Vancouver are numbered referencing styles.

Text matching software

Your university may subscribe to text matching (also called plagiarism detection) software. These tools search the internet and university assessment repositories to find any text in your assignment that matches to other sources, including websites, scholarly literature, grey literature, and other student assignments. If you have the opportunity to submit a draft assignment to such software before you submit your final assignment, please do so. Use of this software will generate a report and alert you to any matches. This will allow you to use your referencing (from this chapter) and paraphrasing (from Writing Assignments chapter) skills to correctly attribute all the ideas in your work and avoid plagiarism. You may need to check with your university contact person for help interpreting the report. Turnitin and iThenticate are examples of software that match text to detect – and help students avoid plagiarism.

Bibliographic software

Your university may make bibliographic software such as EndNote, Mendeley, RefWorks, Paperly, or others available to students to download to their personal computers and devices. Such software can assist you with referencing. If you would like to use a bibliographic software program, please note that it takes time to learn to use this software effectively. Please be aware that until you are fluent in your referencing style, you will not be able to recognise and correct any referencing errors these programs can create.

Conclusion

Working with information is a skill that can be developed. Information literacy is an important skill for study and also for later professional life. Remember that good information sources will always help you to demonstrate your understanding. However, information should always be used to support and enhance (not to replace) your own learning and ideas.

Key points

- Working effectively with information is key to academic success

- There are many types of information including scholarly literature, and grey literature

- Scholarly information is written by academics and is valued at university

- Identify what kind of information you need for a task

- Identify where best to search for that kind of information for the task

- Employ specific search strategies to find the most appropriate information and limit irrelevant sources.

- Evaluate information and think critically about whether it is the ‘right’ kind of information, and discard the non-useful or irrelevant information

- Manage your information sources so you can use them appropriately, and not be overwhelmed by the huge amount of information available to you

- Use information honestly, respectfully and ethically

- Cite and reference your information sources appropriately

References

Angell, K., & Tewell, E. (2017). Teaching and un-teaching source evaluation: Questioning authority in information literacy instruction. Communications in Information Literacy, 11 (1), 95-121. https://doi.org/10.15760/comminfolit.2017.11.1.37

Association of College and Research Libraries. (1989). Presidential Committee on Information Literacy: Final report. http://www.ala.org/acrl/publications/whitepapers/presidential

Del Vicario, M., Bessi, A., Zollo, F., Petroni, F., Scala, A., Caldarelli, G., Stanley, H. E., & Quattrociocchi, W. (2016). The spreading of misinformation online. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 113(3), 554–559. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1517441113

Johnson, M. (2018). Fighting “fake news”: How we overhauled our website evaluation lessons. Knowledge Quest, 47(1), 32–36. https://knowledgequest.aasl.org/

Wineburg, S., Breakstone, J., Ziv, N., & Smith, MM. (2020). Educating for misunderstanding: how approaches to teaching digital literacy make students susceptible to scammers, rogues, bad actors, and hate mongers (Working Paper A-21322). Stanford History Education Group. https://purl.stanford.edu/mf412bt5333

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our colleague, Tahnya Bella for her contribution to the three diagrams in this chapter.