Goals and Priorities

Kristen Lovric and Debi Howarth

Introduction

Every day holds limitless choices for how you can spend your time. Whether consciously or not, those decisions are guided by goals and priorities. Selecting purposeful goals and priorities has the power to put you on track and on time in your journey to academic success. This chapter holds valuable tools for knowing how to get the best out of every day, every week and every year at university. It can move you from floating along with limitless choices, to flying with a focused, intentional direction towards where you want to go.

The chapter begins by explaining the link between goals and motivation. It then shows you how to construct SMART goals and how to use grit to “stick” with them. It also points out the difference between long-term and short-term goals. Next, the chapter explores how to determine priorities, and what to do when you have priority conflicts. This is followed by a helpful discussion of how to complete tasks by breaking them down into the components you need. The chapter finishes with a reminder of how having both deadlines and flexibility can assist you.

Goals Give Motivation

Motivation often means the difference between success and failure. That applies to school, to specific tasks, and to life in general. One of the most effective ways to keep motivated is to set goals. Goals can be big or small. A goal can range from I am going to write one extra page tonight, to I am going to work to get an A in this course, and all the way to I am going to graduate in the top of my class so I can start my career with a really good position. The great thing about goals is that they can include and influence several other things that all work towards a much bigger picture. For example, if your goal is to get an A in a certain course, all the reading, studying, and every assignment you do for that course contributes to the larger goal. You are motivated to do each of those things and to do them well. Setting goals is something that is frequently talked about, but it is often treated as something abstract. Goal setting is best done with careful thought and planning. This next section will explain how you can apply tested techniques to goal setting and what the benefits of each can be.

SMART Goals

Goals need to be specific and represent an end result. They should also be SMART. SMART is an acronym that stands for Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound. When constructed carefully, a SMART goal will help you achieve an end result and support your decision making. Each of the components of a SMART goal will now be described in more detail below.

- Specific—For a goal to be specific, it must be carefully defined. A goal of get a good job when I graduate is too general. It doesn’t define what a good job is. A more specific goal would be something like identify a hospital that recruits graduate nurses and has clear career paths.

- Measurable—To show effect, and report progress, goals need to be measured. What this means is that the goal should have clearly defined outcomes with enough detail to measure them. For example, setting a goal of doing well at university is a bit undefined, but making a goal of graduating with a grade point average (GPA) above 4.0 at university is measurable and something you can work with.

- Attainable—Attainable or achievable goals means they are reasonable and within your ability to accomplish. While a goal to complete six subjects in a semester and work part time is something that would be nice to achieve, the odds that you could make that happen in a semester are not very realistic for most students. However, if you plan to complete three subjects this semester and work part time it may well be more achievable.

- Relevant—For goal setting, relevant means it applies to the situation. In relation to university, a goal of buying a horse to ride to for pleasure on weekends is unlikely to be relevant to your student goals, particularly if you live 100km from campus, but getting dependable transportation to the campus is something that would contribute to your success at university.

- Time-bound—Time-bound means you set a specific time frame to achieve the goal. I will get my paper written by Wednesday is time-bound. You know when you must meet the goal. I will get my paper written sometime soon does not help you plan how and when you will accomplish the goal.

In the following table you can see some examples of goals that do and do not follow the SMART system (see Table 6.1). As you read each one, think about what elements make them SMART or how you might change those that are not.

Table 6.1 Examples of goals that do and do not follow the SMART system

| Goal | Is it SMART? | Comments |

| I am going to be rich someday

|

No | There is nothing specific, measurable, or time-bound in this goal. |

| I will graduate with a GPA of 4.0 by the end of next year. | Yes | The statement calls out specific, measurable, and time-bound details. The other attributes of attainable and relevant are implied. This goal can also be broken down to create smaller, semester or even weekly goals. |

| I will walk for 30 mins each day to help me relieve stress. | Yes | All SMART attributes are covered in this goal, explicitly or implied. |

| I would like to do well in all my courses next semester. | No | While this is clearly time-bound and meets most of the SMART goal attributes, it is not specific or measurable without defining what “do well” means. |

| I will earn at least a 4.0 GPA in all my courses next semester by seeking help from the Learning Advisor (Maths). | Yes | All the SMART attributes are present in this goal. |

| I am going to start being more organised. | No | While most of the SMART attributes are implied, there is nothing really measurable in this goal. |

The most important thing to do when goal setting is to write down the goals, then keep them visible, and revisit each one every couple of weeks to make sure you are on track. Another useful approach to goal setting is to discuss your goals with a critical friend who will help you to be realistic and encourage you to achieve the goals.

Stick With It!

As with anything else, the key to reaching goals is to stick with them, keep yourself motivated, and overcome any obstacles along the way. In the following graphic you will find seven methods that highly successful people use to accomplish their goals (see Figure 6.2).

Keeping focused and motivated can be difficult at university. There are so many other things to do, lots of temptations, and procrastination can be a problem with complex study commitments. How well we persevere towards goal or task completion is sometimes called “grit”. Grit drives us to succeed and to get back up when things seem too hard. Grit is not about how clever you are. It is about how much you keep going until something is finished or accomplished.

This personality trait was defined as grit by the psychologist Angela Duckworth and colleagues (Duckworth et al., 2007). In their study, they found that individuals with high grit were able to maintain motivation in learning tasks despite failures. What the results showed was that grit and perseverance were better predictors of academic success and achievement than talent or IQ. The New York Times best-selling author Paul G. Stoltz has since taken the grit concept and turned it into an acronym (GRIT) to help people remember and use the attributes of a grit mindset (Stoltz, 2015). His acronym is Growth, Resilience, Instinct, and Tenacity. Each element is explained in the table below (see Table 6.2).

Table 6.2 The GRIT acronym

| Growth | Your inclination to seek and consider new ideas, alternatives, different approaches, and fresh perspectives |

| Resilience | Your capacity to respond constructively and to manage all kinds of adversity |

| Instinct | Your capacity to pursue the right goals in the best and smartest ways |

| Tenacity | The degree to which you persist, commit to, stick with, and achieve your goals |

The first step in applying grit is to adopt an attitude that focuses on the end goal as the only acceptable outcome. With this attitude comes an acceptance that you may not succeed on the first attempt—or the nineteenth attempt. Failed attempts are viewed as merely part of the process and seen as a very useful way to gain knowledge that moves you towards success. Sometimes we need to look at how we are doing something to find out why we are unsuccessful. When we are honest about the reasons why, we can then start to manage the situation and set goals. We get back up and start again.

Long-Term Goals and Short-Term Goals

Long-term goals are future goals that often take years to complete. An example of a long-term goal might be to complete a Bachelor of Arts degree within four years. Another example might be purchasing a home or running a marathon. While this chapter focuses on your academic planning, long-term goals are not exclusive to these areas of your life. You might set long-term goals related to fitness, wellness, spirituality, and relationships, among many others. When you set a long-term goal in any aspect of your life, you are demonstrating a commitment to dedicate time and effort towards making progress in that area. Because of this commitment, it is important that your long-term goals are aligned with your values.

Setting short-term goals helps you consider the necessary steps you’ll need to take, but it also helps to chunk a larger effort into smaller, more manageable tasks. Even when your long-term goals are SMART, it’s easier to stay focused and you’ll become less overwhelmed in the process of completing short-term goals.

You might assume that short-term and long-term goals are different goals that vary in the length of time they take to complete. Given this assumption, you might give the example of a long-term goal of learning how to create an app and a short-term goal of remembering to pay your mobile phone bill this weekend. These are valid goals, but they don’t exactly demonstrate the intention of short and long-term goals for the purposes of effective planning.

Instead of just being bound by the difference of time, short-term goals are the action steps that take less time to complete than a long-term goal, but that help you work towards your long-term goals. If you recall that short-term goal of paying your mobile phone bill this weekend, perhaps this short-term goal is related to a longer-term goal of learning how to better manage your budgeting and finances.

Prioritisation

A key component in goal setting and time management is that of prioritisation. Prioritisation can be thought of as ordering tasks and allotting time for them based on their identified needs or value. This next section provides some insight into not only helping prioritise tasks and actions based on need and value, but also how to better understand the factors that contribute to prioritisation.

The enemy of good prioritisation is panic, or at least making decisions based on strictly emotional reactions. It can be all too easy to immediately respond to a problem as soon as it pops up without thinking of the consequences of your reaction and how it might impact other priorities. It is natural for us to want to remove a stressful situation as soon as we can. We want the adverse emotions out of the way as quickly as possible. But when it comes to juggling multiple problems or tasks to complete, prioritising them first may mean the difference between completing everything satisfactorily and completing nothing at all.

One of the best ways to make good decisions about the prioritisation of tasks is to understand the requirements of each. If you have multiple assignments to complete and you assume one of those assignments will only take an hour, you may decide to put it off until the others are finished. Your assumption could be disastrous if you find, once you begin the assignment, that there are several extra components that you did not account for and the time to complete will be four times as long as you estimated. Because of situations like this, it is critically important to understand exactly what needs to be done to complete a task before you determine its priority.

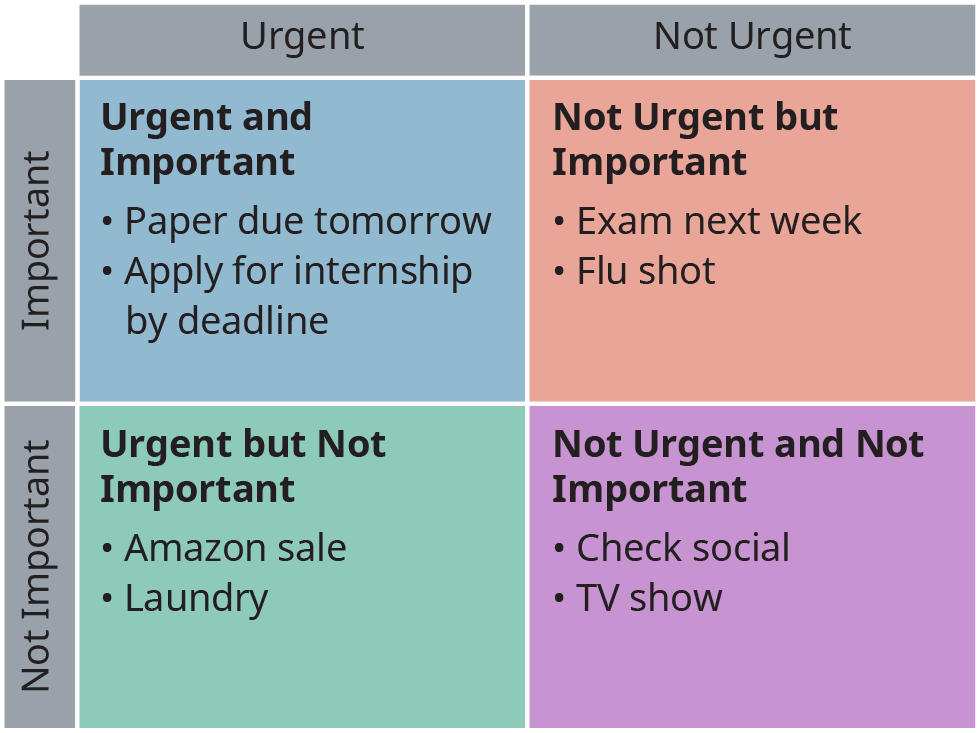

To better see how things may need to be prioritised, some people make a list of the tasks they need to complete and then arrange them in a quadrant map based on importance and urgency. Traditionally this is called the Eisenhower Decision Matrix. Before becoming the 34th president of the United States, Dwight Eisenhower served as the Allied forces supreme commander during World War II and said he used this technique to better prioritise the things he needed to get done.

In this activity, begin by making a list of things you need or want to do today and then draw your own version of the grid below. Write each item in one of the four squares. Choose the square that best describes it based on its urgency and its importance. When you have completed writing each of the tasks in its appropriate square, you will see a prioritisation order of your tasks. Obviously, those listed in the Important and Urgent square will be the things you need to finish first. After that will come things that are “important but not urgent,” followed by “not important, but urgent,” and finally “not urgent and not important” (see Figure 6.4).

Another thing to keep in mind when approaching time management is that while you may have greater autonomy in managing your own time, many of your tasks are being driven by a few different individuals. In some cases, keeping others informed about your priorities may help avert possible conflicts (e.g., letting your boss know you will need time on a certain evening to study; letting your friends know you plan to do a journal project on Saturday but can do something on Sunday, etc.). It will be important to be aware of how others can drive your priorities and for you to listen to your own good judgment. Time management in university is as much about managing all the elements of your life as it is about managing time for class and to complete assignments.

Occasionally, regardless of how much you have planned or how well you have managed your time, events arise where it becomes almost impossible to accomplish everything you need to by the time required. While this is very unfortunate, it simply cannot be helped. As the saying goes, “things happen.” Finding yourself in this kind of situation is when prioritisation becomes most important. When this occurs with university assignments, the dilemma can be extremely stressful, but it is important to not feel overwhelmed by the anxiety of the situation so that you can make a carefully calculated decision based on the value and impact of your choice.

Priority Conflicts

As an illustration, imagine a situation where you think you can only complete one of two assignments that are both important and urgent, and you must make a choice of which one you will finish and which one you will not. This is when it becomes critical to understand all the factors involved. While it may seem that whichever assignment is worth the most points to your grade is how you make the choice, there are actually a number of other attributes that can influence your decision in order to make the most of a bad situation. For example, one of the assignments may only be worth a minimal number of points towards your total grade, but it may be foundational to the rest of the course. Not finishing it, or finishing it late, may put other future assignments in jeopardy as well. Or the instructor for one of the courses might have a “late assignment” policy that is more forgiving—something that would allow you to turn in the work a little late without too much of a penalty.

If you find yourself in a similar predicament, the first step is to try to find a way to get everything finished, regardless of the challenges. If that simply cannot happen, the next immediate step would be to communicate with your instructors to let them know about the situation. They may be able to help you decide on a course of action, or they may have options you had not considered. Only then can you make effective choices about prioritising in a tough situation. The key here is to make certain you are aware of and understand all the ramifications to help make the best decision when the situation dictates you make a hard choice among priorities.

Completing Tasks

Another important part of time management is to develop approaches that will help you complete tasks in a manner that is efficient and works for you. Most of this comes down to a little planning and being as informed about the specifics of each task as you can be.

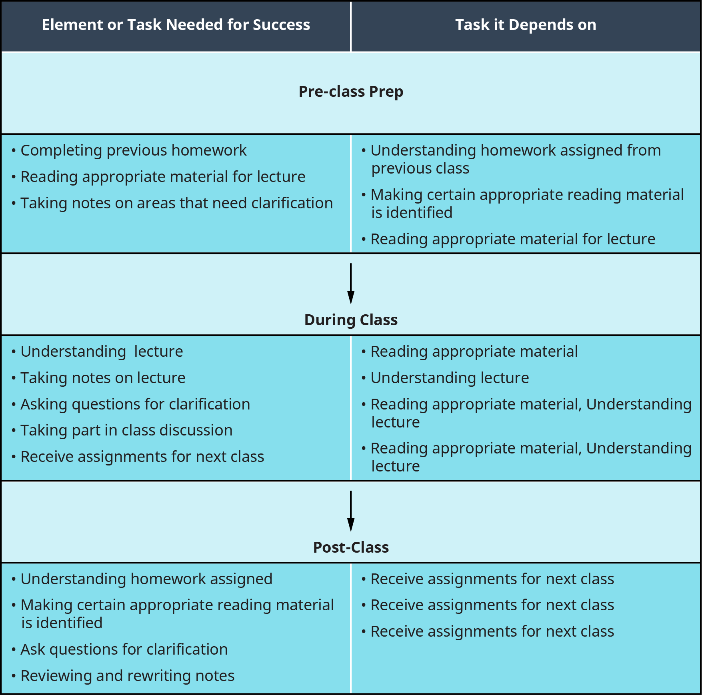

Knowing what you need to do

As discussed in previous parts of this chapter, many learning activities have multiple components, and sometimes they must occur in a specific order. Additionally, some elements may not only be dependent on the order they are completed, but can also be dependent on how they are completed. To illustrate this we will analyse a task that is usually considered to be a simple one: attending a class session. In this analysis we will look at not only what must be accomplished to get the most out of the experience, but also at how each element is dependent upon others and must be done in a specific order. The graphic below shows the interrelationship between the different activities, many of which might not initially seem significant enough to warrant mention, but it becomes obvious that other elements depend upon them when they are listed this way (see Figure 6.5).

As you can see from the graphic above, even a task as simple as “going to class” can be broken down into a number of different elements that have a good deal of dependency on other tasks. One example of this is preparing for the class lecture by reading materials ahead of time in order to make the lecture and any complex concepts easier to follow. If you did it the other way around, you might miss opportunities to ask questions or receive clarification on the information presented during the lecture.

Understanding what you need to do and when you need to do it can be applied to any task, no matter how simple or how complex. Knowing what you need to do and planning for it can go a long way towards success and preventing unpleasant surprises.

Knowing how you will get it done

After you have a clear understanding of what needs to be done to complete a task (or the component parts of a task), the next step is to create a plan for completing everything. This may not be as easy or as simple as declaring that you will finish part one, then move on to part two, and so on. Each component may need different resources or skills to complete, and it is in your best interest to identify those ahead of time and include them as part of your plan.

A good analogy for this sort of planning is to think about it in much the same way you would as preparing for a lengthy trip. With a long journey you probably would not walk out the front door and then decide how you were going to get where you were going. There are too many other decisions to be made and tasks to be completed around each choice. If you decided you were going by plane, you would need to purchase tickets, and you would have to schedule your trip around flight times. If you decided to travel by car, you would need petrol money and possibly a map or GPS device. What about clothes? The clothes you will need are dependent on how long will you be gone and what the climate will be like. If it is far enough away that you will need to speak another language, you may need to either acquire that skill or at least come with something or someone to help you translate. What follows is a planning list that can help you think about and prepare for the tasks you are about to begin.

Knowing what resources will you need

Make a list of the resources you will need to complete a task. The first part of this list may appear to be so obvious that it should go without mention, but it is by far one of the most critical and one of the most overlooked. Have you ever planned a trip but forgotten your most comfortable pair of shoes or neglected to book a hotel room? If a missing resource is important, the entire project can come to a complete halt. Even if the missing resource is a minor component, it may still dramatically alter the end result. Learning activities are much the same in this way. List everything you need.

It is also important to keep in mind that resources may not be limited to physical objects such as paper or ink. Information can be a critical resource as well. In fact, one of the most often overlooked aspects in planning by new university students is just how much research, reading, and information they will need to complete assignments.

Knowing what skills will you need

Poor planning or a bad assumption in this area can be disastrous, especially if some part of the task has a steep learning curve. No matter how well you planned the other parts of the project, if there is some skill needed that you do not have and you have no idea how long it will take to learn, it can be a bad situation.

Imagine a scenario where one of your class projects is to create a poster. It is your intent to use some kind of imaging software to produce professional-looking graphics and charts for the poster, but you have never used the software in that way before. It seems easy enough, but once you begin, you find the charts keep printing out in the wrong resolution. You search online for a solution, but the only thing you can find requires you to recreate them all over again in a different setting. Unfortunately, that part of the project will now take twice as long.

It can be extremely difficult to recover from a situation like that, and it could have been prevented by taking the time to learn how to do it correctly before you began or by at least including in your schedule some time to learn and practise.

Set Deadlines

Of course, the best way to approach time management is to set realistic deadlines that take into account which elements are dependent on which others and the order in which they should be completed. Giving yourself two days to write a 20-page work of fiction is not very realistic when even many professional authors average only six pages per day. Your intentions may be well founded, but your use of unrealistic deadlines will not be very successful. Setting appropriate deadlines and sticking to them is very important.

Be Flexible

It is ironic that the item on this list that comes just after a strong encouragement to make deadlines and stick to them is the suggestion to be flexible. The reason that “be flexible” has made this list is because even the best-laid plans and most accurate time management efforts can take an unexpected turn. The idea behind being flexible is to readjust your plans and deadlines when something does happen to throw things off. The worst thing you could do in such a situation is panic or just stop working because the next step in your careful planning has suddenly become a roadblock. The moment when you see that something in your plan may become an issue is when to begin readjusting your plan.

Adjusting a plan along the way is incredibly common. In fact, many professional project managers have learned that it seems something always happens or there is always some delay, and they have developed an approach to deal with the inevitable need for some flexibility. In essence, you could say that they are even planning for problems, mistakes, or delays from the very beginning, and they will often add a little extra time for each task to help ensure an issue does not derail the entire project or that the completion of the project does not miss the final due date. As you work through tasks, make certain you are always monitoring and adapting to ensure you complete them.

Conclusion

Goal setting and prioritisation are essential in the first year of university and beyond. Learning effective approaches to goal setting and managing priority conflicts takes time, but the steps covered in this chapter provide a strong foundation to get students started. Using a structured approach to identifying achievable goals that are personally meaningful allows you to plan for both short and long-term success. Overtime, prioritisation may also become easier as you gain experience. Keep the key points in mind to help maintain your motivation as you transition into university life.

Key points

- One of the most effective ways to keep motivated is to set goals.

- SMART Goals are a useful structured approach to plan, write down, commit to, and achieve meaningful goals.

- The key to reaching goals is to keep at it, keep yourself motivated, and overcome any obstacles along the way.

- Apply grit and adopt an attitude that looks directly to the end goal as the only acceptable outcome.

- Setting short-term goals helps you consider the necessary steps you’ll need to take to achieve your long-term goals, but it also helps to chunk a larger effort into smaller, more manageable tasks.

- Prioritisation is a key component of goal setting and time-management which involves ordering tasks, and allotting time for them based on their identified needs or value.

- If you find that you have a priority conflict, make certain you are aware of and understand all the ramifications to help make the best decision.

- Knowing what you need to do and planning for it can go a long way towards successfully completing tasks. You might need specific resources or skills.

References

Duckworth, A.L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M.D., & Kelly, D.R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92 (6), 1087–1101. https://doi:10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087.

Stoltz, P. G. (2015). Leadership Grit. Leader to Leader, 78, 49–55. https://doi-org.ezproxy.usq.edu.au/10.1002/ltl.20205