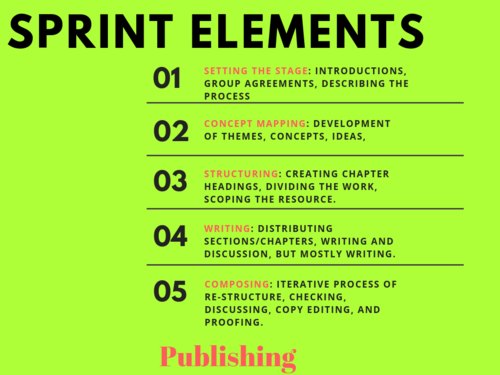

Now that you have gone through the groundwork to plan and set up a successful sprint, let’s take a look at the process for a sprint itself. Depending on the context and goals, there are different stages that you can include in a book or resource sprint. We have adapted the structure framework described by D. Berry and M. Dieter:[1]

- Set the stage.

- Begin concept mapping. Develop themes, concepts, ideas, develop ownership, etc.

- Establish structure. Creating chapter headings, divide the work, scope the book.

- Write. Distribute sections/chapters, writing and discussion, but mostly writing.

- Composition. An iterative process of re-structuring, checking, discussing, copy editing, and proofing.

- Publication.

In the section below, we have unpacked these stages and included activities that can be used to support each stage. Sprint approaches and activities will vary considerably depending on the duration of the sprint and the overall goals.

Set the stage

Sprints will involve participants working together for a long period of time in a situation that can involve personal dynamic and vulnerability as participants are involved in sharing their work and receiving feedback. Setting the stage can help to build trust and connection between participants and ensure that they are able to successfully contribute and provide constructive feedback to one another throughout the sprint.

Icebreakers

Icebreakers can be used at the outset of the sprint to help to build rapport and connection between participants. They also are a way for sprint participants to learn about each other beyond their roles within the sprint. Although it can be tempting to not include an icebreaker, these activities can help ensure the sprint’s success. Use icebreakers that are aligned with the goal and the processes of the sprint.

Introductions

Introductions can be a powerful way to connect the group. Rather than typical introductions, consider questions that move beyond the participants’ roles or titles at work. For example:

- Where did you grow up?

- Why are you participating in this sprint?

- What do you bring to this group?

Superpowers

Everyone gets two to three minutes to share what “superpower” they bring to the team. Other members of the team give examples of how this superpower could contribute to the team’s success over the next few days.

Things we did not know

Each person writes five things about themselves on an index card that the other people in the group will not know. The facilitator collects these cards in a container and then goes around the room and each participant picks a card not their own. Each participant reads the five interesting things on the card and the other participants guess who the person is.

Group agreements

Group agreements, or working agreements, are simply mutually agreed “contracts” for the way a group chooses to interact. They’re often manifested in written lists of behaviours, such as “turn mobile phones off” or “raise a hand if you would like to speak.”

Group agreements can be a very useful facilitation tool. They have the potential to head off the vast majority of “difficult” behaviour and domination in any group processes. This opens up the way for the quieter voices and the least assertive to play a more active role in the group. But it would be a mistake to think that the group agreement does all that on its own. Negotiating an agreement raises the consciousness of the group about issues of group dynamics and participation, but it needs to be supported by a constant flow of reminders, gentle (and some less gentle) challenges, and body language (gestures and facial expressions).

Tips for negotiating a successful agreement:

- Ensure the agreement is proposed in practical terms. For example, “What does this tool do for us as a group?” People need to understand what they’re being asked to commit to. A clear rationale is essential for this.

- Take the time to negotiate the agreement fully at the start. It sends a clear message to the group that you, the facilitator, are serious about participation.

- See every agreement as negotiating space. This is important for those who find the dominant culture difficult to participate in, for whatever reason. Negotiate for full participation. The agreement should answer the question, “How will this behaviour make this meeting accessible for all of its participants?” rather than just reinforcing mainstream norms.

- List specific behaviours, not vague concepts. “Encourage participation” is laudable, but vague. Ask the group what behaviours will encourage participation and list those instead.

- Negotiate a culturally appropriate agreement. Not all cultures share the same behavioural norms. One voice speaking at a time might be polite and sensitive group behaviour in one culture. “No interrupting” might be appropriate for an agreement in that context. However, another culture might find more animated conversation, with several voices speaking and frequent interruption, the norm.

- Go back to the underlying purpose of the agreement – what do we want to achieve? A safe space for everyone to feel able to contribute, have their voice heard, and their point respected? So work from that—it may lead you to behaviours like “No interrupting,” but equally it may not.

- Get full agreement. Don’t simply read through a proposed list of behaviours for agreement and end with an “Is that OK?”, accepting the resulting low murmur as assent.

- Use the negotiation process to cement your mandate to facilitate with the group. It’s a two-step process: “Can you all sign up to these behaviours?” and “Can I have your mandate to support you in behaving this way?”

Concept mapping

The concept-mapping stage of the sprint is a time to come together to map out the process and goals of the sprint. By the end of this section of the sprint, you will have established a shared understanding of what you hope to achieve by the end of the sprint and how you will go about completing the sprint. During this time, the facilitator will need to ensure that there is a group agreement on both the sprint goals and the process.

Sprints often include activities that facilitate the development of shared goals for the textbook, resources, or case studies that you are creating. By creating a set of shared goals, you can ensure that the group is developing a cohesive resource. Examples of approaches to goal setting could include a conversation, a facilitated activity that has participants brainstorm goals and cluster goals on sticky notes, or even using dot voting to determine the goals to focus on.

Brainstorming and clustering

Ask participants, individually or in pairs, to come up with key goals for the sprint based on your overall sprint goals, and write these on post-it notes. For example, a goal could be to develop the first three modules of a resource or to create a prototype for a book. Then have everyone stick these goals up on a whiteboard or flip chart and group them by theme. The facilitator then works through the goals with the group, asking questions such as, “Is this goal possible within this time? Does this work for the audience who will be using the resource? How might these goals be connected/aligned? What is missing?”

Mapping the process

Collaboratively working together to map out or draw out the process for the sprint helps the facilitator ensure that all participants are aware of the sprint process that you will be following. This activity also allows the process to be changed to fit the participants’ goals and can be referred to throughout sprint checkpoints to ensure that everyone is on task and helps to revise the process as needed as it progresses. One approach to this activity is to start with the end point in mind for the sprint, i.e., we will have created a textbook draft. During the UBC Case Study, one of the facilitators began with the endpoint: “By the end of the sprint, we will have created at least one case study per discipline, written about three case-studies from each of our perspectives,” and asked participants, “What will it take to get there?” From there, the group mapped out the checkpoints for each of the two days and used these throughout the sprint to ensure that everyone was on task adapting these as needed.

Structuring

The next step in a sprint is to start working together to structure the content or resource together. This is an important sprint element because the group can work together to develop a shared structure for the content and collaborate to create an approach and a way of envisioning the overall resource. It also provides the group information about what resources will be required to complete the text or resource. An approach to this often used in textbook sprints is to work to develop a textbook table of contents for the text.

In the case study sprint, the facilitator stuck one piece of flip chart paper on the wall for each case study heading that were determined together before the sprint. Participants worked individually and wrote down on post-it notes and brainstormed how their case study would include each of these elements. Through this activity, participants were able to see what each other was planning for their case study. As a debrief, the participants were asked what sections they wanted to revise, remove, or add to the case study template, and they decided to add a learning objective section.

By structuring the content, the facilitators have a content blueprint/plan that they can refer back to during the writing process, and this can also help to create consistency and a shared understanding of the content structure. The facilitator can also use this to create headings, sections, or groupings in the final product.

Creating a shared table of contents

The facilitator puts the goals for the resource/book on a whiteboard. Each participant works on their own using small post-its and writes down specific topics that they feel should be included in the resource. They add each of these post-its to the board, and as they do this, they begin to cluster them. The facilitator has the group cluster the post-it notes together. When the group is satisfied with a particular cluster of post-it notes, the facilitator places a large post-it note above the small cluster of topics and works with the groups to come up with a chapter title for the topics. The facilitator continues this process until the group has come up with a table of contents and chapter titles for the resource.

Drafting/storyboarding

In design sprints and boot camps, there is typically an ideation stage during which participants brainstorm and begin to draft ideas for their chapter or case. Approaches to this can include having participants create a storyboard, write a simple outline, or do a quick-write activity. As a debrief, the facilitator can lead a short feedback session with the group to provide suggestions for early revisions.

Writing

At the heart of the sprint process is focused writing time. Once the creators have set goals and completed the initial structuring, they can start writing their section of the case study, textbook, or resource. In some sprints, the creators can work in small groups and collaboratively write. In other contexts, each creator works individually to create a section of the content. During the UBC Case Study sprint, each participant worked individually in short 1.5- to 2-hour intensive writing blocks to create their case studies.

Composing

Feedback and revision cycles

Although lots of writing time is essential in sprints, this needs to be balanced with time for feedback and revisions. This can be set up as a series of checkpoints during the writing process where creators can share what they have completed so far, gather feedback from the group, and work on revisions. Finding creative ways of having the participants share and respond to each other’s work can maintain energy and momentum and encourage sharing.

Approaches to sharing include lighting talks, short presentations (three to five minutes) by each participant going over their main points, and open-discussion time for feedback. During the Sustainability Case Study Sprint, each of the participants wrote a case study about sustainability for their discipline. As a way to develop their case further and receive feedback, they had students read their case study and give feedback. They also shared their case study with a faculty member from another discipline who added a section to the case about how an economist, legal expert, etc., would respond to this case through their disciplinary lens. This provided feedback to the original creator and expanded the overall case study itself.

Publication and sharing

Arthur Gill Green, a geography instructor who participated in the geography textbook sprint, suggests that the text or resource that you develop should be viewed as always in a perpetual draft state. The resource will continue to be adapted and revised after the end of the sprint. With open textbooks and other OER, there is often a continuous development process. Reminding the writers that the content does not have to be perfect can ease stress about creating a final perfect project and allow them to focus on completing the goal of the sprint.

Attributions

- “Group agreements” from Facilitating Group Agreements [PDF] by Rhizome.coop. Adapted by the authors. © CC BY-NC-SA (Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike)

- David M. Berry and Michael Dieter, "Everything you wanted to know...," BookSprints, https://www.booksprints.net/2012/09/10/everything-you-wanted-to-know/ (accessed February 28, 2019). ↵