12

William Moore

Introduction

Congratulations[1]! You’ve earned your graduate degree and landed a job in academia. This in itself is quite a feat! Your mentors have helped prepare you to conduct your own research, secure extramural funding, and speak publicly about your research. Perhaps you’ve even had teaching experience or better yet, received some formal training in pedagogy. Your new supervisor mentioned in passing that you would be expected to serve as an academic advisor for some of your students. Piece of cake, you thought, all you need is a course catalog and a list of degree requirements, right? How hard can it be?

A couple of weeks prior to the first day of class, you receive a list of advisees and appointment times from the registrar’s office. Reality sets in. You are in the hot seat. Maybe you’re confident. Maybe you’re a nervous wreck as the weight of responsibility rests heavily on your shoulders. If you find yourself even somewhat in the latter category, allow me to remind you of the adversity you’ve already overcome. Your success to this point means that you have a recipe for success in your toolbelt, but perhaps you’ve been too busy writing your dissertation to think about it.

This chapter will discuss…

- Skills and characteristics of effective advisors.

- How to develop and hone your own advising philosophy.

- The merits and drawbacks of various advising techniques and strategies.

The purpose of this chapter is not to provide an exhaustive explanation of advising techniques and sociological defenses for each one, but rather to help bring your recipe for success to the front of your mind; to serve as a companion as you take time to ponder the contents of and begin to articulate your recipe. Finally, I am here to offer some research-based advice, from a “been-there-done-that” standpoint, to help strengthen your advising philosophy and explore the merits of other techniques and strategies as you learn to tweak your recipe for success to meet the needs of an infinitely diverse student population.

Before we dive into the content of this chapter, consider the following questions: What interpersonal skills and styles facilitate great advising? At which of these skills are you particular adept? Which of these skills could admittedly use work? How do you present yourself in such a way that your advisees recognize your warm, caring advisor heart? How do you train your ear to be one that listens and hears your students? Are any of the thoughts that have just crossed your prefrontal cortex more important than others? An entire book could be written on any of these topics. However, the goal not being to provide an exhaustive list, I urge you to consider these questions as you read these next few pages.

Behaviors and Characteristics of an Effective Advisor

While it has been reported that students tend to be most satisfied with the advising administered by an advising center staff compared to that offered by individual faculty (Belcheir, 1999a), it is understood that some readers work at institutes of higher education that do not provide their faculty with such an asset. Before moving on to discuss the various aspects of this section, note that personal experience has so far found it to be true that “you can only lead a horse to water,” so to speak. Research supports this observation in that extraverted students have reported to have perceived higher quality and more satisfying advising experiences than introverted students (Mottarella et al., 2004). The study also found that a majority of students, regardless of their personality, desire to establish warm and supportive relationships (Mottarella et al., 2004). This supports the rationale that advisors should take time to reflect on their own interpersonal skills and relationship-building approach, such that they are best suited to facilitate this warm and supportive environment. Thus, this chapter will focus on things that can be done and should not be done to strengthen the ability to “lead the horse to the water.”

Approachability

The introduction to this chapter mentions the weight of responsibility placed upon advisors. The purpose of its mention is twofold; (1) to strengthen their confidence by serving as a reminder that they’ve already overcome great adversity to get to the position they’re in and (2) to reiterate that advising is not a task to be taken lightly as it is critical for the academic success and personal development of the students (Amenkhienan & Kogan, 2004; Latopolski, 2018). Student success is very much associated with the quality of advising. In a meta-analysis of studies on doctoral student attrition and persistence, the single most frequently occurring finding was that successful program completion is related to the degree and quality of contact between students and advisors (Centra, 2004). Warmth and support from the advisor have also been shown to be important factors in advisee satisfaction (Mottarella et al., 2004). For a warm and supportive interaction to occur, advisors must first position themselves in a way that invites interaction; in other words, advisors should consciously do everything in their power to make themselves approachable.

Age Doesn’t Matter… But If It Does, New Faculty Have an Advantage

While some advising techniques might require extensive time, dedication, and practice to master, rest assured that neither youth nor inexperience hinder approachability. One common misconception about advising is that those who have extensive teaching experience tend to make the best advisors. This can be refuted by noting that freshly minted products of higher education are more likely to be able to empathize with the students compared to more seasoned faculty. A study (Eberdt, 1968) aimed at defining selection criteria for secondary school counselors studied characteristics of secondary teachers who had been rated as most and least approachable by their students. Interestingly, the data indicate that teaching experience and even intellectual ability tend to impede approachability. In fact, personality factors are suggested to be as important, if not more so, than academic ability (Eberdt, 1968). More recently, it has been shown that student satisfaction with an advisor is more likely be dependent on the advisor’s interpersonal skills and style than on their advising approach (Mottarella et al., 2004). Indeed, research has shown that the advising climate is dependent on the extent to which an advisor provides facilitative conditions such as listening and hearing (Whiteley et al., 1975).

Relationship Building Requires a Time Commitment

Regardless of the advising approach, the establishment of a warm and supportive relationship can be foundational (Mottarella et al., 2004). Even an intrusive and/or prescriptive approach to advising (discussed later) does not require cold, unsupportive, uncaring advising (Mottarella et al., 2004). Also, despite it having been reported that students who have previously received academic advising tend to indicate that female advisors are typically more empathetic (Nadler & Nadler, 1993), this may be because female faculty have been shown to devote more time to advising than their male colleagues (Bennett, 1982). Thus, in addition to facilitating a warm and supportive advising environment, it is of paramount importance that an appropriate amount of time is devoted to advising.

This begs the question, what sort of advising tasks should merit a significant time investment? An advising appointment can be likened to an exam. Time should be spent in preparation in order to ensure success; however, regardless of time spent preparing, if the actual process is rushed, it is easy to leave points on the table. In other words, it is important to allow ample time to engage with advisees. During an advising appointment, the advisee should be the focus of the advisor’s undivided attention. The following remarks by John Dewey (Dewey, 1938 p. 79) support this rationale:

Once more, it is part of the educator’s responsibility to see equally two things: First, that the problem grows out of the conditions of the experience being had in the present and that it is within the range of the capacity of students; and, secondly, that it is such that it arouses in the learner an active quest for information and for production of new ideas.

To put Dewey’s remarks in the context of advising, students/advisees exist in a certain social environment, and time should be taken to be cognizant of this in anticipation of the advising interaction. Further, it would be beneficial to spend a few minutes allowing the student to engage in a dialogue with the advisor about this context. Advisors must also take the time to ensure that any prescriptive tasks are within their advisees’ capacity to succeed. Finally, time should be spent helping students see the relationships between their academic milieu as well as the relationships that exist between this milieu and their goals. Such attention contributes to the intellectual growth of the student by pushing them to strive to be active learners and productive scholars in a broader context.

If the reader is anything like the author of this chapter, this seems a daunting task. This work is being written from the perspective of a person of admittedly poor memory, especially pertaining to faces, names, and details about the lives of other people. Further, the author’s office epitomizes disorder. These personal flaws require extra steps to ensure that the approach to advising is organized so that time allocated for advising can be maximally invested in the advisee.

First, I recommend that advising files/folders have a distinct color. It is helpful to only use this color folder for advising. There should also be a special place for advising folders and for all things advising. The contents of advising folders don’t have to be anything extraordinary. Keep it simple. Academic records, an updated program of study, and some minute profile information (i.e. career goals, extracurricular activities, likes/dislikes) is generally sufficient. However, a typically disorganized person might find it helpful to have a place in the folder to take notes that can be used to interact with the student both personally and academically. For example, seeing a student’s name in a school publication about some meritorious endeavor could be noted so that congratulations can be extended. If a student discloses any likes/dislikes (e.g., they hate art), make note of that. Further, interview notes regarding students’ career goals (this likely will be updated multiple times for most students) can be recorded here. This information can be used to build a personal relationship with each student, serving as a cornerstone for the Deweyan-inspired approach to guiding student learning during advising.

Certainly, these things require an initial time investment, but they are incredibly valuable. Before every advising appointment, time should be spent reading through these notes, and jotting down any thoughts/concerns that should be discussed during the next appointment. Regardless of the method(s) used, it is imperative that enough time is allowed in the advising appointment to be able to engage with the student personally, allow the advisee to discuss their concerns and reason for the appointment, allow the advisor to discuss their concerns with the advisee, and emphasize how everything that has been discussed points towards the greater goal of the advisee’s calling.

Disposition/Demeanor: “Why don’t you smile?”

The word “approachable” is a descriptor for someone who is friendly, welcoming, and pleasant. What are some features of people who are “approachable”?

Research in behavioral psychology has shown that there is a fundamental motivation to approach environmental aspects that apparently confer benefit and a fundamental motivation to withdraw from those that are apparently harmful (Schneirla, 1959). Rotteveel & Phaf (2004) showed that the perception of happy expressions resulted in arm flexion, which has been associated with positive information (Rotteveel & Phaf, 2004). In layman’s terms, this literature can be summarized with a common interrogative from a wise great aunt, often directed at her great nephew as a child; In her thick Southern accent, she’d ask “Honey, why don’t you smile?”

The tendency to gravitate toward and away from certain facial demeanors is deeply ingrained in human nature. Even infants have been shown to gravitate toward their mothers when they are smiling, but not when they are frowning (Sorce et al., 1985). Assuming this primitive tendency is continuous throughout the human lifespan, it is certainly a worthwhile topic to cover in the pursuit of becoming more approachable to postsecondary students. Indeed, it has been suggested that smiles are useful in establishing and maintaining effective interpersonal relationships as they are indicators of trustworthiness and cooperative intent (Owren & Bachorowski, 2001). A more recent study showed that movement toward an approaching target was more likely when the target displayed a positive emotional state (Miles, 2009), thus supporting the rationale that there is an active primitive tendency to gravitate toward facial expressions perceived as positive.

Though initiating contact with a certain demeanor is a good starting point, please note that this is NOT a suggestion to always smile or put on any one set of “approachable” facades, but to rather consider them during interactions with people. For one, it is not inherent in everyone’s personality to always be cheerful or otherwise able to put themselves in a good mood on command. A cheerful demeanor can be forced to some extent, but human biochemistry is simply often not conducive to being in a good mood 24/7/365. Further, it could be perceived as “fake” by students. Worse, this might inadvertently lead a student to pursue academia under the false pretense that such a career is all positive.

As important as all of these things are, it must be recognized that cultural differences must also be considered and accounted for. What is perceived as “approachable” may very well differ from person to person based on their background. For example, one study showed that Chinese participants relied more on the eyes to represent facial expressions while Western Caucasians tended to rely more on the mouth and eyebrows, suggesting that cultural distinctions might indeed cause a misinterpretation of an emotional portrayal during cross-cultural communication (Jack et al., 2011). In short, advisors should take time to get to their students in order to put themselves in the position to facilitate an environment that best supports their educational pursuits.

Availability

A study cited earlier in this chapter noted that students tend to prefer advising centers over peer counselors largely because the students perceived peer counselors as not being either proactive or available when needed (Belcheir, 1999b). It has been further shown that committed, purposeful communication with an advisor is associated with increased student motivation and involvement (Astin, 1999). Fielstein (1987) showed that 28.9% of students, when interviewed about their advising experiences, noted that their advisor’s personal acquaintance with them was a high priority (Fielstein, 1987). Not surprisingly, research collectively suggests that students tend to be most pleased with faculty advisors who are available and accessible (Alexitch, 1997).

Access to and availability of faculty advisors is an area of concern as advising is an additional item on a plate already filled with quality teaching, research, committee work, outreach, and so on (Gnepp et al., 1980; Habley & Others, 1988). Complicating the issue is the fact that advising tends to be of low priority in tenure and promotion consideration processes (Habley & Others, 1988; Spencer et al., 1982). All of these things understandably culminate in reasonable faculty members simply NOT placing advising at the top of their priority lists. A 1987 ACT survey indicated that most faculty spent 1-5% of their time advising and that most faculty have contact with their advisees two or fewer times in an academic term (Habley & Others, 1988). Sadly, this is a disservice to the students, resulting in many institutes of higher learning falling short of student expectations. Admittedly, one of the reasons for mentioning this seemingly obvious characteristic is based on personal conversations with students regarding their description of an ideal advisor. Almost all of them note some variation of “the advisor must be available” as the number one factor of importance in their assessment of advising.

A student whose advisor is not accessible is missing out on the wealth of information and experience that the faculty advisor could provide if they were available/accessible. For example, a faculty member can usually provide detailed information about courses, programs, and (cough cough) other professors. They can also provide a rationale for a requirement and point students toward otherwise unknown career opportunities (Habley & Others, 1988).

Education would be a far greater experience for students if only advisors who wanted to advise were allowed to serve in that capacity, and if those advisors were given some sort of relief of other duties to provide reasonable incentive for diligently serving in this highly important capacity.

An individual tasked with academic advising is highly encouraged to recall their importance in the students’ success and to do everything they can to take an interest in their students. This includes taking the time to strengthen their advising skills. Perhaps the most simple thing that can be done is to BE AVAILABLE. This is not saying that every hour outside of the classroom has to be spent in the office, but that there is merit in being proactive about this. Advisors should post and keep office hours, and bend over backward to make sure their advisees (and their students for that matter) know the schedule or can easily find it. Advisors should encourage advisees to drop by for an informal chat. One method I use is to keep a single-serve coffee maker in the office that students are always free to use; if the advisor isn’t available in person, they should provide some means for student access. If nothing else, simply checking email once an hour during regular business hours is helpful. Social media accounts can also be employed, for example by having a page set aside where students can interact with their advisor.

To take availability a step further, active mental availability should be considered in addition to physical availability. A former chemistry professor would literally sit in his office chair, facing the door, during office hours and do nothing else (maybe twiddle his thumbs) but wait for students to stop by. His students knew that he was there to actively listen, understand, and to provide feedback based on their needs because the sole purpose of his office hours was not to catch up on work, watch videos on YouTube, or read a book for leisure, but to provide them help. The intention of this example is not to suggest that such extreme measures are necessary for everyone, but if a student is to be helped, their needs must be understood. If advisors are to understand the needs of their students, they must actively listen—listen in such a way that the student isn’t just heard, but that they also feel heard, seen, and understood (Ranglund et al., 2017).

When a student visits an advisor in their office, that student should have the advisor’s undivided attention until they can confidently leave with a solution or a plan for whatever the concern might have been.

Adaptability

Generally speaking, most approaches to teaching and advising can be categorized as “teacher-centered,” “student-centered,” or some combination of the two. This section will give some examples of advising strategies. As the shift is made to those descriptions, it is important to understand that all of these ideas (as well as others) should be in the “advising tool-belt” to be used or neglected as each occasion calls for it. However, the most important tool in the belt should be an adaptor that allows for the ability to adjust to the individual needs of the students.

A purist approach, in most any field, is likely to end in disaster. This will be a recurring theme in the coming sections. As highly adored as student-centered teaching (and advising) is, it is obvious that even these approaches require some aspect of teacher-centered guidance. If that were not so, teachers would be overpriced and obsolete relics of antiquity. Indeed, Dewey was somewhat critical of this approach in isolation (Dewey, 1938) as is a more recent article arguing that allowing students the absolute freedom to learn in an unguided environment is antithetical to the psychological principles encompassing working memory (Kirschener et al., 2006). This brings to memory an inspirational quotation: “The best teachers are those who show you where to look, but don’t tell you what to see.” This quotation beautifully encompasses both sides of the teacher-/student-centered paradigm by serving as a reminder that teachers and advisors should be guides—coaches on the sidelines, but that as coaches, must be flexible enough to know not only where to look, but how to inspire students to look until they’ve found the answer. If every student is unique in terms of experience, personality, and level of academic achievement (most are), this implies that an advisor must be limitlessly and existentially adaptable in order to inspire and motivate each individual student to press on towards the goal.

What Advisors Can Learn From Other Disciplines

Ascertaining and Admitting a Circle of Competence

The ability of a person to know what they don’t know is arguably as important, if not more so, than what they do know. Being able to honestly divulge personal strengths and limitations falls under the category of personal competency and integrity. To some extent, this defines who a person is (Ranglund et al., 2017). Students are incredibly perceptive. With respect to advising, a former department chair at Averett University gave a piece of simple yet wise advice. He said, “If you don’t know something, don’t act like you do; they can see right through that. Tell them that you will find the answer and get back to them.” This advice nicely parallels the concept of “circle of competence,” which was originally intended as a principle of investing developed by Warren Buffet and Charlie Munger (Chairman/CEO and Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, respectively). The crux of the model is that everyone has the ability to make intelligent decisions in some area(s), but no one is an expert on everything (Parrish, 2013), and only people who are arrogant, foolish, or purposely deceptive pretend to be. As Charlie Munger put it, “A money manager with an IQ of 160 and thinks it’s 180 will kill you. Going with a money manager with an IQ of 130 who thinks it is 125 could serve you well.”

Munger’s words could be adapted to derive an equally wise advising principle by replacing “money manager” with “academic advisor.” This is true for several reasons, the most obvious being the plethora of elective courses (even at small liberal arts universities). Students have quite a bit of agency in exploring fringe interests as they pursue their primary goals (Thelin & Hirschy, 2009). This is great for students, and given the personal opportunity to impart change, more choices would be advocated for. However, so many options pose a challenge for advisors. At some point advisors will need to be guided as they guide their students. Advising does not afford the option to quarantine in a niche circle of competence; advisors don’t have the luxury of picking pitches; in fact, doing so would be antithetical to adaptability. However, they do have the responsibility to be open with their pupils about what they do and do not know. This is of paramount importance because transparent humility will foster trust in the advisor/advisee relationship. It is essential to develop a pattern of giving advice that advisees find to be trustworthy as this will foster the expectation that the given advice is always from an informed position. Because advisors do have a circle of competence, it is critical that advisees trust their advisors enough to know that professional remarks with respect to advice, feedback, criticism, commendations, etc., are credible and trustworthy.

More Than an Advisor: A Coach

To build on the coaching analogy, we will use pieces of a previously published coaching model for advising (McClellan & Moser, 2011). Thus far the importance of being available (physically and mentally), adaptable, and transparent about a circle of competence has been discussed. Together, application of these ideas builds rapport and assists the student to begin to both identify their own path to success and to devise a plan to achieve it. A good coach doesn’t stop there, but intently watches so as to be able to evaluate the success (or lack thereof) of the plan. The coach offers feedback regarding the mishaps and helps to identify steps that aid the future direction towards success.

Evaluation of the success of the plan requires the advisor to pose questions that allow the students to reflect on their efforts (McClellan & Moser, 2011). Such questions help the advisor become more aware of the student’s thought process; the answers might identify details of the situation of which the advisor might not have been previously aware, and should be considered as future directions are proposed (McClellan & Moser, 2011). Questions also serve as a means of assessment of the student’s problem-solving ability (McClellan & Moser, 2011) thus directing the advisor to move toward a more “hands-on” or “hands-off” advising approach (Intrusive/Proactive Advising).

Considering future directions from which to attack a problem involves brainstorming. The advisor should be prepared to ask questions that encourage the activity. Though there are a number of questions that could be useful, one of particular personal appeal is, “If our positions were reversed, and you were offering me advice, what would you tell me?” Follow-up questions may similarly draw from what the student anticipates another involved party might recommend (McClellan & Moser, 2011). It is perfectly acceptable for the advisor to offer ideas as well, however, it is best to do so after the student has had an opportunity to think, so as to avoid intrusive advising. This is also to be done with humility: An advisor should not arrogantly insist or imply that their ideas are better than any others, but rather offer them as additional ideas that might be of value (McClellan & Moser, 2011).

Once several viable ideas have been presented, the coaching model of advising suggests that the advisor help the student evaluate and choose an approach to be molded into a plan with which to address the problems (McClellan & Moser, 2011). Finally, advising as a coach requires seeing the plan through. The student must be encouraged to stick to the plan and to give an account of their progress (McClellan & Moser, 2011).

More Than an Advisor: A Counselor

This chapter has alluded to the fact that advising entails much more than the academic milieu. With the personal development of students being dependent on advising to some extent, part of the time used to prepare for advising sessions should be spent considering that an advisor may be called upon to assist students with interpersonal relationships, personal challenges, work/life balance, co-curricular activities, and so on (Kuhn et al., 2006). Having served as an advisor for only a few years, I will attest to what more experienced advisors have noted for decades: Students often have complicated personal issues that, if left on their own, will be barriers to success (Kuhn et al., 2006). Any barrier to the success of the students is a barrier to the success of an advisor. Thus, the academic component of advising must happen in the context of advisees’ personal needs, values, goals, and circumstances (Kuhn et al., 2006).

Discernment can be aided by active listening skills, however, such challenges call for advisors to demonstrate empathy. That is, compassion must be shown in times of stress, the cause of which can vary greatly in its range of severity. Placing a high value on education tends to be accompanied by an innate concern about students, and as previously noted, active listening is an exemplary fruit of empathy. Actively listening to students’ concerns (big or small) lends emotional support (Hybels & Weaver, n.d.). Emotional support as it pertains to extracurricular affairs can move perilously close to the line of most academic advisors’ competency circles. While crossing the boundaries of certain competencies may not be particularly harmful, crossing this boundary can be. Most advisors are not mental health counselors. However, psychology literature suggests that empathy is associated with positive prognoses in therapeutic environments (Laska et al., 2014). Therefore, it stands to reason that empathetic listening, as the best source of outside help is deductively determined, can be helpful.

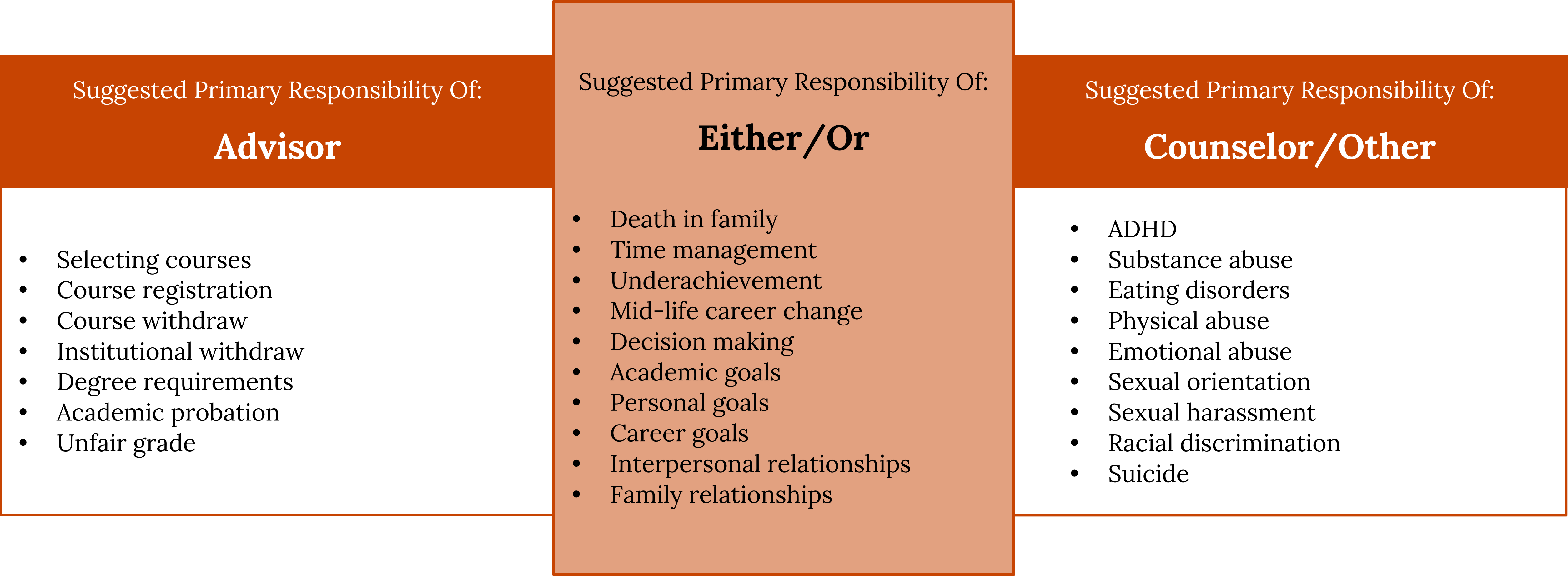

The focus of this section is clearly not as enjoyable as the rest of the chapter. However, the responsibility to help early career faculty brace themselves for an occasional encounter with a student who has a need in which they are unable and/or unqualified to intervene must be acknowledged. Indeed, there are scenarios that may very well surface in an advising meeting that should be referred to other campus resource offices including student success and/or counseling. The reader is encouraged to introduce themself to the folks who work in these offices so that they are prepared to turn to them when situations arise that call for their expertise. Seeking help from another office (or another faculty member) is the advisor’s responsibility. By seeking help, the discipline required of the advisor to admit her/his circle of competence is demonstrated as part of the fulfillment of duty to ensure that the students’ personal and academic success is as attainable as it possibly can be. Kuhn et al. (2006) presents an excellent list of issues with which an advisor might be confronted along with an indicator that generally indicates whether the issue is addressable by most academic advisors (Figure 12.1).

General Approaches to Advising

The purpose of this section is to describe some practical approaches to advising. To preface, it has been argued since the 1960s, by those conducting psychotherapy research, that the nature of the professional relationship, as opposed to any specific approach or technique, is most contributive to client satisfaction (Beutler et al., 1994; Rogers, 1992; Truax & Carkhuff, 1967). Thus, any of the following approaches to advising might be beneficial at some point. However, it suggested that these ideas be kept as tools in a toolkit to be deployed when the situation calls for it, and further, that these ideas be considered to exist on a sliding scale—that is, there are varying degrees of implementation. The approach taken and the degree to which it is taken will differ depending on the individual needs of the student. For instance, students may prefer aspects of either a developmental or prescriptive approach to advising so far as certain relational elements are demonstrated by the advisor (Mottarella et al., 2004).

Developmental Advising

Many advisees in science departments approach their advisors with an interest in pursuing careers in medicine. Thus, from this perspective, it would be remiss if the concept of osteopathic medicine weren’t mentioned somewhere in this chapter. A short justification clause for developmental advising seems to be the perfect place. Many people are not aware that there are two doctoral degrees in the United States that allow for full licensure to practice as a physician in any area of medicine. A Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO) is trained to practice medicine from the perspective that the human body is a three-part being—an integrated whole comprised of mind, body, and spirit. It is often noted that a broken spirit can be every bit as painful as a broken bone. Further, a DO recognizes the paramount importance of the reciprocal relationship between structure and function and that wellbeing is often affected by factors outside of what is purely physical. This holistic approach to medicine is somewhat analogous to a holistic approach to advising that is developmental in nature. Developmental advising recognizes that the academic pursuits of the student can’t be completely understood without seeing the whole student.

Together, developmental and prescriptive advising have historically dominated the field of advising (Barbuto et al., 2011; Crookston, 1972). Developmental advising is a controversial topic as the literature defines it in several different ways. Further, it has been criticized as aiming toward goals that are outside the realm of the traditionally held outcomes of higher education (Bloland et al., 1994; Hemwall & Trachte, 1999). Indeed, developmental advising is typically depicted as a model of counseling to the end of personal growth (Hemwall & Trachte, 2005). Though some academics are critical of such an approach, as this chapter has noted, this author believes that academic advising is far more than an occupation that promotes mere intellectual growth, but that intellectual growth is only achievable so long as personal growth is the cornerstone that supports the intellectual pursuit. Developmental advising supports this rationale as it allows advisors to embrace advising as a practice that recognizes students as multidimensional and should be supported emotionally, physically, morally, economically, and vocationally as well as intellectually (Boyle et al., 2012). Thus, despite criticism of the approach, developmental advising has been shown to be the ideal advising approach for university students (Gordon, 1994; Winston & Sandor, 1984).

To advise a student with such a goal, the student-advisor relationship should allow the advisor to pose questions whose answers will reveal the students’ goals. To approach advising with a developmental focus, awareness of the students’ current state is necessary (Grites, 2013). As mentioned earlier, it is helpful to note these goals on the inside of advising files so that time can be taken to discuss progress during each meeting. These goals include those directly related to education, but also include career and personal goals (Winston et al., 1982). These broader goals might require a student to acquire a skill or seek professional experience outside of the institution.

Once those goals have been noted, advisors should help their students put together a plan of action that aims to accomplish these goals while promoting both intellectual and personal development. Keep in mind that the students may need the advisor to help find and use institutional, community, and perhaps personal resources to realize those goals (Winston & Sandor, 1984). It should also be understood by both parties that this is a shared commitment (Grites, 2013). The student must be honest and direct; the advisor must be tolerant and able to inspire; both student and advisor must be trustworthy, adaptable, and dependable (Grites, 2013).

The argument that developmental advising involves extracurricular factors, and falls outside the scope of most job descriptions is well taken. However, most educators have an intrinsic understanding of human dignity and the fact that their brothers and sisters of humanity are far from cookie-cutter and are incredibly complex. It is thus natural that a developmental approach would be at the core of every other practical or theoretical approach to academic advising.

Prescriptive Advising

Prescriptive advising is somewhat of a contrasting approach to developmental advising. While the latter recognizes the art of advising as a broad discipline that requires some degree of care for aspects of student life that go beyond academics, prescriptive advising mostly limits advising to matters that are directly related to academics. The advisor-advisee relationship in prescriptive advising has been compared to the physician-patient relationship in that the patient/student is given information necessary for progression of health/intellect (Barbuto et al., 2011). Such an approach uses advising sessions explicitly for course selection, registration, degree requirements, discussions of curriculum, and so on (Drake, 2011).

It has been noted that prescriptive advising is only a theoretical concept (Crookston, 1972). When considering the physician-patient relationship, it is nearly impossible to imagine the field of medicine without compassion, which by definition comes from some degree of personal concern. Regardless of whether it is ever practiced in the purest sense, the philosophy of prescriptive advising is incredibly important as the academic pursuits of students are at the heart of the student-advisor relationship. Service as an advisor requires accurate knowledge of the degree requirements (Crosbie, 2005) or at the very least, where to find them. While it is not typically in the nature of a teacher’s heart to default to prescriptive advising, there are students who frankly want, and in some sense demand, prescriptive advising. Indeed, a recent study showed that 17 out of 429 surveyed students preferred prescriptive advising (Hale et al., 2009). While prescriptive advising is obviously not the most commonly preferred approach, it should always be kept in mind that different students find value in different advising techniques, and advisors should be ready to employ the technique that is most conducive to each student’s success.

Burn Crookston’s work (1972) provides an accurate depiction of prescriptive advising. Personal experience has shown that students who prefer this approach view their academic advisors as a source of information about the university. They want a cut-and-dried answer or plan to answer a question about an academic topic. A prescriptive advisor would hypothetically answer the specific questions, but would not address more comprehensive concerns (Crookston, 1972). To reiterate, such an approach is not the personal default, and the literature supports the rationale that pure prescriptive advising is not a viable option in the modern era (White, 2020).

Even students who seem to seek a prescriptive advising session should be challenged to at least be inwardly inquisitive about their own questions, and should be pressed to consider their rationale for certain questions. For example, if a student were to inquire about the process of adding a minor, changing a major, or enrolling in an elective that is outside of their field, the inquiry could be justifiably met with a question that is on the cutting-edge of advising: “Why?” While there is often solid reasoning for students to ask such questions, occasionally, a student has simply made a rash and/or illogical decision, and they need to be protected from themself.

In this respect, while prescriptive advising might be the elemental approach for some students, it might be more appropriate to view such an advisor-advisee relationship as that between a client and a financial advisor. Dave Ramsey, who is a radio personality specializing in personal finance, often says with respect to investing that “the only way to get hurt on a roller coaster is to jump off.” All three of the professions mentioned in this section (physician, financial advisor, academic advisor) call for a compassionate professional with genuine care for the success and well-being of those who are dependent on their advice. It would be next to impossible to ask a compassionate person to be so emotionally withdrawn as to allow someone under their care to jump off the metaphorical roller coaster without at least trying to prevent such a catastrophe. Thus, despite being mostly theoretical, this section addresses prescriptive advising as it entails some fundamental concepts at least and handful students will likely be encountered during the career of an advisor who need or prefer prescriptive direction. However, both the literature and personal experience suggest that it would be unwise (perhaps careless) to become a prescriptive purest.

Intrusive/Proactive Advising

Regardless of whether an approach is developmental, instructive, or a combination of the two, students might also be well-served by varying degrees of intrusiveness. Touted as a means of reaching at-risk students (Heisserer & Parette, 2002), intrusive advising involves proactively anticipating problems before they arise (Varney, 2007).

Natural inclination would be to divide this section into two by labeling one “hands-on advising” and the other “hands-off advising.” However, there is little to no literature discussing the effects of a purely “hands-off” approach to academic advising. And, to be clear, it is also well noted that intrusive/proactive advising should not be construed as “hand-holding” (Upcraft & Kramer, 1995). In fact, it is based on the idea that the advisor and student have shared responsibility for success. Thus, my personal contention is that most students require some balance of “hands-on” and “hands-off” advising; or as will be considered here, some degree of intrusiveness.

Truly “hands-on” advising would in essence be “hand-holding” as it would point out every possible roadblock, offer a set of instructions describing how to avoid/get around the roadblocks, and not allow a student to make a move that is likely to result in failure of any sort. Such an approach would likely be disadvantageous because it devalues the learning process by withholding valuable teachable moments that strengthen character and discipline. In fact, being too intrusive can negatively affect a student’s attitude toward advising, causing them to eschew help (Herget, 2017). The opposite extreme of this sort of advising would allow a student to encounter every problem on their own without any warning and then perhaps work with the student to solve the issues once they arise. This “hands-off” approach would also be problematic because there are some situations that are not so easily remedied.

Intrusive advising nicely balances these two ideas. That is, advisors should aim to be inviting, friendly, and warm while still implementing the touch of tough love that students need for optimal growth (Cannon, 2013). For example, as obvious as it might seem to you, many new college students aren’t inclined to contact their advisors. Being aware of this common pitfall allows the advisor to avoid it by proactively making the initial contact with the students. This can be as simple as providing a personal introduction, briefly noting what is expected from the advisees and what the advisees should expect from their advisor (Cannon, 2013). The students might also be encouraged to reply with their own introduction (Cannon, 2013). It is also appropriate to ask the students if there is anything that the advisor should know about them and whether there is anything that they would like to know about the advisor.

To give an example of the balance between “hands-on” and “hands-off” advising that intrusive advising offers, consider advising a student with respect to course load. First, regardless of the ratio of “hands-on” to “hands-off” used, the importance of being prepared for advising appointments has already been noted. To reiterate, it is wise to use the prior afternoon to review any notes about the student and their grades, extracurricular activities, and personal situations. With that, the advisor should be prepared to pose questions that allow for some degree of intrusiveness. It is well-known that there is a bit of finesse to class scheduling, and varying degrees of intrusiveness can be used to help students avoid potential pitfalls.

Generally, a full-time course load can range from 12-18 credit hours. Information gathered from these intrusive questions can be used to offer students advice based on experience. For example, a student who holds a full-time job outside of school and has historically struggled academically might benefit more from a course load of about 12 hours whereas someone who has a history of academic excellence and has no job outside of school might be able to handle a heavier course load. Perhaps it is also typical for students who take course X along with course Y to perform better or worse compared to those who take them separately.

A “hands-off” approach to advising would tell the students where to find the degree requirements, perhaps show them a sample 4-year schedule leading to degree completion, and have them select and enroll in classes on their own. The only intervention that a “hands-off” advisor might make would be to keep a student from taking a course for which they have not met a prerequisite. On the other hand, an exclusively intrusive advisor might go so far as to not approve a schedule that they believe to be less than optimal.

A perfect balance of intrusive advising as it is intended would provide students with all the information and warnings of historical areas of struggle, but still allow them to make their own decisions. With this approach, both the advisor and the student share the responsibility for success.

Concluding Remarks

I hope that you are now keenly aware that academic advising is a multifaceted art. Unfortunately, there is no one right way to advise students. There is no one right way to advise any “category” of students because every student has a unique set of life experiences, needs, priorities, and goals. If you are ever (un)fortunate enough to advise students at more than one institution, you’ll also find that advising differs quite drastically depending on the structure of the institution (e.g., community college, liberal arts schools, technological institutes).

Regardless of where you are in preparation for your first/next advising appointment, my advice to you is to be prepared to show your students how much you care. Take some time to get to know your advisees. Students have argued that interest in students’ personalities, recognition of their merits, and trust in them tend to contribute to the improvement of the advisor-advisee relationship, which translates to increased student satisfaction and subsequently to improvement in academic performance (Fielstein, 1989). Regardless of how well you know your advisees, observe them as multidimensional human beings (they are). Approaching advising with this mindset will push you to be adaptable regarding the needs of your students. Perhaps most importantly, remember to be available to your students both physically and mentally.

I suggest that you spend some time in mental preparation for the fact that you will inevitably be called upon to coach students through problems—some of which are emotionally taxing to say the least. Regardless of the circumstances that arise in your world of advising, I hope that this work has encouraged you to reflect on your advising persona. Further, I hope that it has given you some ideas/tools that might be useful as you begin to master the exhilarating art of advising.

Finally, I implore you to not be afraid of advising. With confidence and a spirit of humility, embrace it, enjoy it, and rest assured that you are very much up to the task.

Reflection Questions

- What personal changes could you make to improve advising quality?

- Does the physical and emotional environment in which you advise inspire trust in the advisor/advisee relationship? What steps can you take to improve this?

- Without considering any particular student, what advising approach(es) are you most likely to implement?

- Despite your tendency to gravitate towards certain approaches to advising, what steps might you take to embrace methods that are outside your comfort zone?

References

Alexitch, L. R. (1997). Students’ educational orientation and preferences for advising from university professors. Journal of College Student Development, 38, 333–342.

Amenkhienan, C., & Kogan, L. (2004). Engineering students’ perceptions of academic activities and support services: Factors that influence their academic performance. College Student Journal, 38, 18.

Astin, A. W. (1999). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education. Journal of College Student Development, 40(5), 518–529.

Barbuto, J., Story, J., Fritz, S., & Schinstock, J. (2011). Full range advising: Transforming the advisor-advisee experience. Journal of College Student Development, 52, 656–670. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2011.0079

Belcheir, M. (1999a). ERIC – ED433772—Student Satisfaction and Academic Advising. AIR 1999 Annual Forum Paper, 1999-Jun. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED433772

Belcheir, M. (1999b). Student Satisfaction and Academic Advising. AIR 1999 Annual Forum Paper. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED433772

Bennett, S. K. (1982). Student perceptions of and expectations for male and female instructors: Evidence relating to the question of gender bias in teaching evaluation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 74, 170–179.

Beutler, L. E., Machado, P. P., & Neufeldt, S. A. (1994). Therapist variables. In A. E. Bergin & S. L. Garfield (Eds.), Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavioral Change (4th ed.). Wiley.

Bloland, P., Stamatakos, L., & Rogers, R. (1994). Reform in student affairs: A critique of student development. ERIC Counseling and Student Services Clearinghouse.

Boyle, K. M., Lowery, J., & Mueller, J. (2012). Reflections on the 75th Anniversary of the Student Personnel Point of View (Vol. 1). ACPA — College Student Educators International.

Cannon, J. (2013). Intrusive advising 101: How to be intrusive without intruding. Academic Advising Today, 36(1). https://nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Academic-Advising-Today/View-Articles/Intrusive-Advising-101-How-to-be-Intrusive-Without-Intruding.aspx

Centra, J. A. (2004). Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research (vol. 19). Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Crookston, B. (1972). A developmental view of academic advising as teaching. NACADA Journal, 29(1), 78–82.

Crosbie, R. (2005). Learning the soft skills of leadership. Industrial and Commercial Training, 37(1), 45–51.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience & Education (First Touchstone Ed. 1997). Kappa Delta Pi. http://www.schoolofeducators.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/EXPERIENCE-EDUCATION-JOHN-DEWEY.pdf

Drake, J. (2011). The role of academic advising in student retention and persistence. About Campus, 16(3), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.20062

Eberdt, M. (1968). A study of most approachable and least approachable teachers as rated by high school students. The School Counselor, 15(3), 209–214.

Fielstein, L. L. (1987). Student preferences for personal contact in a student-faculty advising relationship. NACADA Journal, 7(2), 34–40.

Fielstein, L. L. (1989). Student priorities for academic advising. Do they want a personal relationship? NACADA Journal, 9(1), 33–38.

Gnepp, J., Keating, D. P., & Masters, I. C. (1980). A peer system for academic advising. Journal of College Student Personnel, 21.

Gordon, V. (1994). Developmental advising: The elusive ideal. NACADA Journal, 14(2), 71–75.

Grites, T. J. (2013). Developmental academic advising: A 40-year context. NACADA Journal, 33(1), 5–15. https://meridian.allenpress.com/nacada-journal/article/33/1/5/139404/Developmental-Academic-Advising-A-40-Year-Context

Habley, W. R., & Others. (1988). The Status and Future of Academic Advising: Problems and Promise (p. 275) [RIE]. American Coll. Testing Program. National Center for the Advancement of Educational Practices.

Hale, M., Graham, D., & Johnson, D. (2009). Are students more satisfied with academic advising when there is congruence between current and preferred advising styles? College Student Journal, 43, 313–324.

Heisserer, D., & Parette, P. (2002). Advising at-risk students in college and university settings. College Student Journal, 36(1), 69–84.

Hemwall, M. K., & Trachte, K. C. (1999). Learning at the core: Toward a new understanding of academic advising. NACADA Journal, 19(1), 5–11.

Hemwall, M. K., & Trachte, K. C. (2005). Academic advising as learning: 10 organizing principles. NACADA Journal, 25(2), 74–83.

Herget, A. (2017, January 9). Intrusive academic advising: A proactive approach to student success. HigherEd Jobs.

Hybels, S., & Weaver, R. L. (n.d.). Communicating Effectively (11th ed.). McGraw Hill Education.

Jack, R. E., Caldara, R., & Schyns, P. G. (2011). Internal representations reveal cultural diversity in expectations of facial expressions of emotion. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 141(1), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023463

Kirschener, P., Sweller, J., & Clark, R. (2006). Why minimal guidance during instruction does not work: An analysis of the failure of constructivist, discovery, problem-based, experiential, and inquiry-based teaching. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep4102_1

Kuhn, T., Gordon, V. N., & Webber, J. (2006). The advising and counseling continuum: Triggers for referral. NACADA Journal, 26(1), 24–31.

Laska, K. M., Gurman, A. S., & Wampold, B. E. (2014). Expanding the lens of evidence-based practice in psychotherapy: A common factors perspective. Psychotherapy, 51, 467–481. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034332

Latopolski, K. S. (2018). Students’ Experiences of Mattering in Academic Advising Settings [Doctoral dissertation]. The University of Alabama.

McClellan, J., & Moser, C. (2011). A practical approach to advising as coaching. NACADA Clearinghouse of Academic Advising Resources Website. http://www.nacada.ksu.edu/Resources/Clearinghouse/View-Articles/Advising-as-coaching.aspx

Miles, L. K. (2009). Who is approachable? Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(1), 262–266.

Mottarella, K. E., Fritzsche, B. A., & Cerabino, K. C. (2004). What do students want in advising? A policy capturing study. NACADA Journal, 24(1 & 2), 48–61.

Nadler, M. K., & Nadler, L. B. (1993). The influence of student sex and instructor sex on academic advising communication. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 4, 119–130.

Owren, M. J., & Bachorowski, J.-A. (2001). The evolution of emotional experience: A “selfish-gene” account of smiling and laughter in early hominids and humans. In Emotions: Current Issues and Future Directions. T.J. Mayne and G.A. Bonanno (Eds.) (pp. 152–191). Guilford Press.

Parrish, S. (2013). The “Circle Of Competence” theory will help you make vastly smarter decisions. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/the-circle-of-competence-theory-2013-12

Ranglund, O. J. S., Danielsen, A., Kionig, L., & Vold, T. (2017). Securing trust, roles and communication in e-advising—Theoretical inputs. Electronic Journal of E-Learning, 5(3), 211–219.

Rogers, C. R. (1992). The necessary and sufficient conditions of therapeutic personality change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 827–832.

Rotteveel, M., & Phaf, R. H. (2004). Automatic affective evaluation does not automatically predispose for arm flexion and extension. Emotion, 4(2), 156–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1528-3542.4.2.156

Schneirla, T. C. (1959). An evolutionary and developmental theory of biphasic processes underlying approach and withdrawal. In Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, M.R. Jones (Ed.), 1–42. University of Nebraska Press.

Sorce, J. F., Emde, R. N., Campos, J. J., & Klinnert, M. D. (1985). Maternal emotional signaling: Its effect on the visual cliff behavior of 1-year-olds. Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 195–200. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.1.195

Spencer, R. W., Peterson, E. D., & Kramer, G. L. (1982). Utilizing college advising centers to facilitate and revitalize academic advising. NACADA Journal, 2(1).

Thelin, J. R., & Hirschy, A. S. (2009). College students and the curriculum: The fantastic voyage of higher education, 1636 to the present. NACADA Journal, 29(2), 9–17.

Truax, B. B., & Carkhuff, R. R. (1967). Toward Effective Counseling and Psychotherapy. Aldine Atherton.

Upcraft, M., & Kramer, G. (1995). Intrusive advising as discussed in the first-year academic advising: Patterns in the present, pathways to the future. Academic Advising and Barton College, 1–2.

Varney, J. (2007). Intrusive advising. Academic Advising Today, 30(3).

White, E. R. (2020). The professionalization of academic advising: A structured literature review—A professional advisor’s response. NACADA Journal, 40(1), 5–9.

Whiteley, J. M., Brukhart, M. Q., Harway-Herman, M., & Whiteley, R. M. (1975). Counseling and student development. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 26, 337–366.

Winston, R. B., Ender, S. C., & Miller, T. K. (1982). Developmental Approaches to Academic Advising. New Directions for Student Services. Jossey-Bass.

Winston, R. B., & Sandor, J. A. (1984). Developmental academic advising: What do students want? NACADA Journal, 4(1), 5–13.

Figure and Table Attributions

- Figure 12.1 Adapted under fair use from Kuhn, T., Gordon, V. N., & Webber, J. (2006). The advising and counseling continuum: Triggers for referral. NACADA Journal, 26(1), 24–31. Graphic by Kindred Grey.

- How to cite this book chapter: Moore, W. 2022. Personalized Advising that Is Purposely Inconsistent: The Constants of Great Advisors and the Variability that Demands Adaptability. In: Westfall-Rudd, D., Vengrin, C., and Elliott-Engel, J. (eds.) Teaching in the University: Learning from Graduate Students and Early-Career Faculty. Blacksburg: Virginia Tech College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. https://doi.org/10.21061/universityteaching License: CC BY-NC 4.0. ↵