1 Open Educational Resources Defined

Isaac Mulolani

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this chapter, the reader will be able to:

- Define open educational resources

- List the different Creative Commons licenses

- Describe the 5R framework

Open Educational Resources

In the 1980s Richard Stallman initiated the Gnu Project to write a complete operating system free from constraints on the use of its source code.[1] This led to the Free Software Definition by the Free Software Foundation in 1986:

The definition was further refined to its current modern form to include the following four freedoms (See Wikipedia):

- The freedom to run the program as you wish, for any purpose (freedom 0).

- The freedom to study how the program works, and change it so it does your computing as you wish (freedom 1). Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

- The freedom to redistribute copies so you can help your neighbor (freedom 2).

- The freedom to distribute copies of your modified versions to others (freedom 3). By doing this you can give the whole community a chance to benefit from your changes. Access to the source code is a precondition for this.

The key issue to note is that Freedom 1 and 3 require source code to be available because studying and modifying software without its source code is highly impractical. This is a key element of the open-source movement – providing source code for each project for others to be able to modify as needed. In 1989, the Gnu General Public License was published. Although there is no commonly agreed upon definition of Free and Open Source Software (FOSS), various groups maintain approved lists of licenses (see Wikipedia). From the list provided on Wikipedia, there are over 50 different open source licenses currently available.

This glance at the open-source movement is deliberate because it was a pre-cursor to open educational resources. Under the open-source movement, there were people who were creating educational materials for their courses putting them under an open license (GPL) and sharing them with others in the community.

Open-source doesn’t just mean access to the source code. The distribution terms of open source software must comply with the following criteria:

The open-source software tools commonly used were TeX-based tools in the majority of the cases. TeX user groups (TUG mirrors) sprang up across the globe where people would share code snippets with one another and sometimes links to source code that was downloadable for users. The global sharing that has been occuring in the open-source community since the 1990s forked into the open educational resource movement in the 2000s.

Open Licensing

One of the key issues borrowed by the open education movement from the open-source movement is the idea of open licensing. What sets copyrighted resources apart from open resources is the license placed on open resources. These licenses allow users to remix, rework, adapt, retain redistribute copies of the resource. In short, the open license provides the user of a resource with a set of permissions allowing some or all of these activities. Before describing licensing, a description of the allowable permissions is provided.

The 5R Framework

David Wiley provided this 5 R framework that is key to defining open educational resources.[2] Open Educational Resources refers to any copyrighted work that is either

- in the public domain or

- licensed in a manner that provides everyone with free and perpetual permission to engage in the 5R activities.

These 5 R activities/permissions are:

- Retain – make, own, and control a copy of the resource (e.g., download and keep your own copy)

- Revise – edit, adapt, and modify your copy of the resource (e.g., translate into another language)

- Remix – combine your original or revised copy of the resource with other existing material to create something new (e.g., make a mashup)

- Reuse – use your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource publicly (e.g., on a website, in a presentation, in a class)

- Redistribute – share copies of your original, revised, or remixed copy of the resource with others (e.g., post a copy online or give one to a friend)

It is important to note that not all the open licenses provide all five of these permissions. Some of them carry restrictions that the user needs to be aware of by noting license requirements. For example, some licenses restrict commercial use while others require the adapted resource be released under the same license as the original.

The ALMS framework

As David Wiley explains on the opencontent.org definition page, Creative Commons licenses give us permissions to exercise the 5 R’s (reuse, revise, remix, redistribute, retain), but poor technical choices can make open content less open (and thus, harder to work with).

The ALMS Framework provides a way of thinking about those technical choices and understanding the degree to which they enable or impede a user’s ability to engage in the 5R activities permitted by open licenses. The framework includes four buckets (or whichever your preferred container is) that questions about the technical openness of an OER likely fit into. Here are the descriptions of each bucket.

(This material is based on original writing by David Wiley, which was published freely under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 license at http://opencontent.org/definition/)

Access to Editing Tools

Is the open content published in a format that can only be revised or remixed using tools that are extremely expensive (e.g., 3DS MAX)? Is the open content published in an exotic format that can only be revised or remixed using tools that run on an obscure or discontinued platform (e.g., OS/2)? Is the open content published in a format that can be revised or remixed using tools that are freely available and run on all major platforms (e.g., OpenOffice)?

Takeaway: Can you edit the OER without the need for specialized or expensive tools?

Level of Expertise Required

Is the open content published in a format that requires a significant amount technical expertise to revise or remix (e.g., Blender)? Is the open content published in a format that requires a minimum level of technical expertise to revise or remix (e.g., Word)?

Takeaway: Would most faculty be able to edit the OER at their current skill level?

Meaningfully Editable

Is the open content published in a manner that makes its content essentially impossible to revise or remix (e.g., a scanned image of a handwritten document)? Is the open content published in a manner making its content easy to revise or remix (e.g., a text file)?

Takeaway: Can all parts of the OER be edited?

A word about the ALMS framework is in order with respect to this particular resource. In the remaining chapters of this guide, tools that require different levels of expertise will be described and discussed. Some of the tools that are word processors tend to require lower to medium technical expertise. In the later chapters, the open-source tools tend to require higher technical expertise.

Self-Sourced

Is the format preferred for consuming the open content the same format preferred for revising or remixing the open content (e.g., HTML)? Is the format preferred for consuming the open content different from the format preferred for revising or remixing the open content (e.g. Flash FLA vs SWF)?

Takeaway: Can you edit the OER directly or is a separate editable file needed?

Creative Commons Licenses

For OER, the most widely used open licenses are the Creative Commons (CC) licenses, which make it possible for educators to freely and legally share their work. Creative Commons licenses work with copyright to automatically give users a set of usage rights pertaining to that work. When something is licensed with a Creative Commons license, users know how they are allowed to use it. Since the copyright holder retains copyright, the user may still seek the creator’s permission when they want to reuse the work in a way not permitted by the license.

License Terms

Creators or copyright holders who wish to apply a Creative Commons license to their work can choose the conditions of reuse and modification by selecting one or more of the restrictions listed below. Every Creative Commons license except the Public Domain designation requires users to give attribution to the creator of the work. Other restrictions are optional and may prevent reuse in unintended ways, so care is suggested in selecting a license.

| Icon | Right |

Description |

|

Attribution (BY) |

Licensees may copy, distribute, display, perform and make derivative works and remixes based on it only if they give the author or licensor the credits (attribution) in the manner specified by these. Since version 2.0, all Creative Commons licenses require attribution to the creator and include the BY element. |

|

Non-Commercial (NC) |

Licensees may copy, distribute, display, perform the work and make derivative works and remixes based on it only for non-commercial purposes. |

|

Share Alike (SA) |

Licensees may distribute derivative works only under a license identical to (“not more restrictive than”) the license that governs the original work. (See also copyleft.) Without share-alike, derivative works might be sublicensed with compatible but more restrictive license clauses, e.g. CC BY to CC BY-NC.) |

|

No Derivative Works(ND) |

Licensees may copy, distribute, display and perform only verbatim copies of the work, not derivative works and remixes based on it. Since version 4.0, derivative works are allowed but must not be shared.Note: works licensed with the ND restriction are not considered OER.

|

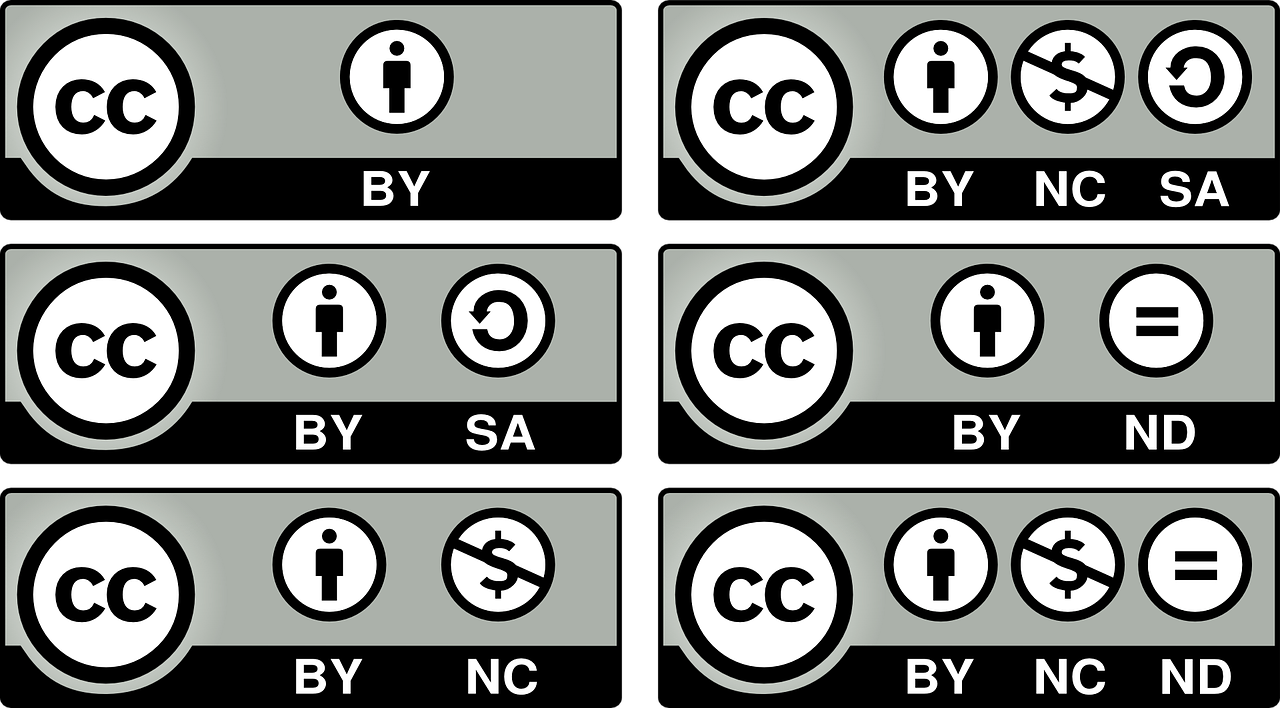

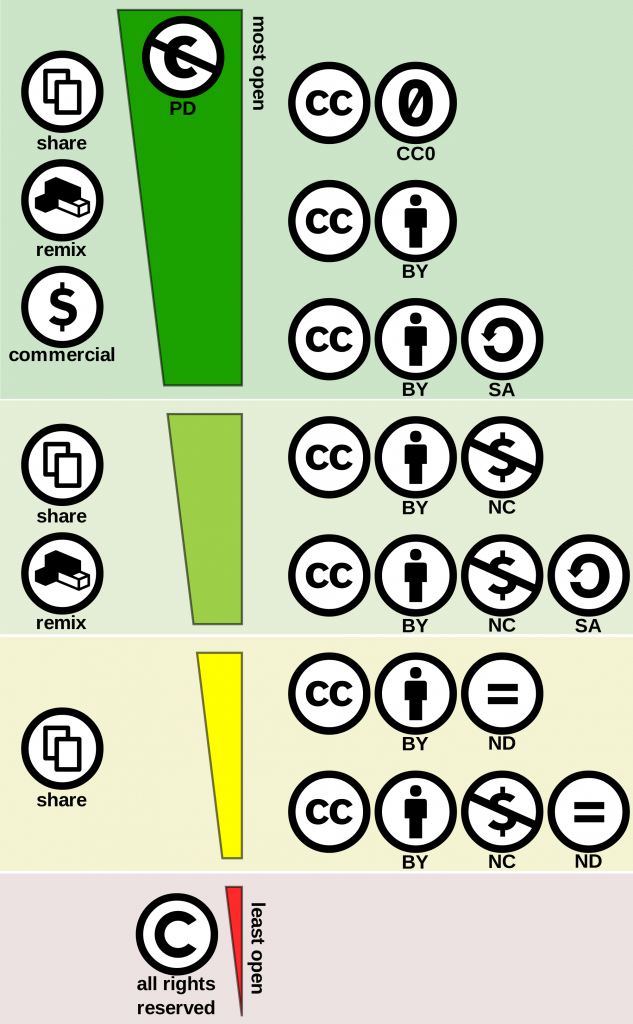

License Types

There are six possible licenses that can be derived from combining the license terms described above and assigned to materials by the original creator or author. To learn more about the license designs, rationale, and structure of Creative Commons licenses, please read About the licenses by Creative Commons.

It is helpful to point out that the two Creative Commons licenses at the bottom of the second stack in the image (CC-BY-ND and CC-BY-NC-ND) are not open educational resources. For open educational resources in education, the power comes from being able to revise, remix and redistribute. When the resources can only be used as they are then we are almost back to using copyrighted content. The following graphic depicts this fact.

Technical Expertise

Before moving on to describing the technologies and platforms that can be used to create open resources, it will be useful to provide categories of technical expertise needed for prospective tools. This will be useful in helping OER authors determine which tools would be most appropriate for their level of technology expertise. The following are the three categories of skills required:

- Low-tech Skills: The simplest way to create educational resources is by using familiar word processing tools such as Microsoft Word, Google Docs, or Libre Office. This software includes most of the features needed for standard content, and the file can be easily exported as a PDF or printed.

- Medium-tech Skills: Another common way to create or edit educational resources is to create a website or hosted resource. This could be in the form of a blog, a static website, or a wiki. WordPress can be a great tool for these sorts of medium-tech projects.

- High-tech Skills: There are a number of platforms that provide professional tools for authoring content, and some are very easy to use. A common tool used by OER projects is Pressbooks (in which this text is published), a publishing software that makes it easy to produce interactive e-books and other text-based content

These levels will be used to categorise all the tools that will be discussed in the remaining chapters of this guide. Table G 1.1 in Appendix G summarises the technology skills required for each of the tools discussed in this guide.

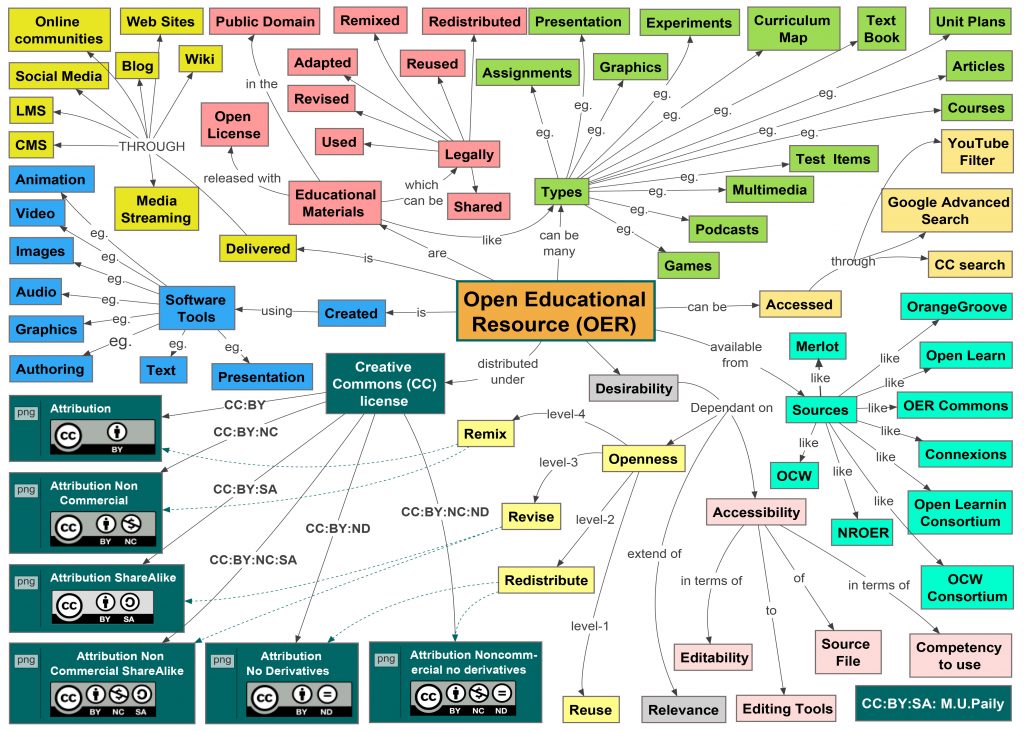

To summarise this chapter, it seems fitting to end with the following OER Concept Map.

For the remainder of this resource, the focus will be on technology tools that can be used to create open educational resources. Both commercial and open platforms will be briefly described along with key features. A useful crowd-sourced tool was created by Abbey Elder in 2018 under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. This tool has a list of additional platforms particularly with a focus on those useful for assessment purposes.

References

- The Four Freedoms. 23 January 2014. “I [Matt Mullenweg] originally thought Stallman started counting with zero instead of one because he’s a geek. He is, but that wasn’t the reason. Freedoms one, two and three came first, but later he wanted to add something to supersede all of them. So: Freedom zero. The geekness is a happy accident.”

- Free Software Foundation (2018-07-21). “What is free software? Gnu Project – Free Software Foundation (Footnote).” “The reason they are numbered 0, 1, 2 and 3 is historical. Around 1990 there were three freedoms, numbered 1, 2, and 3. Then we realized that the freedom to run the program needed to be mentioned explicitly. It was clearly more basic than the other three, so it properly should precede them. Rather than renumber the others, we made it freedom 0.”

- Hilton, John L. III; Johnson, Aaron; Stein, Jared; and Wiley, David. (2010). The Four R’s of Openness and ALMS Analysis: Frameworks for Open Educational Resources. Faculty Publications. 822. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/822/.

- Menke, William (2018). UH OER Training, https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/oertraining2018/. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- OpenLearn Create, About Creative Commons Licenses.

- Open Source Initiative, The Open Source Definition, https://opensource.org/osd. Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Stallman, Richard. “FLOSS and FOSS.” www.gnu.org. Archived from the original on 2018-09-16. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- Stallman, Richard. “The Free Software Definition.” Free Software Foundation. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- Stallman, Richard (February 1986). “Gnu’s Bulletin, Volume 1 Number 1.” Gnu.org P.8. Retrieved on 2022-01-07.

- Vetter, G. (2009). “Commercial Free and Open Source Software: Knowledge Production,Hybrid Appropriability, and Patents.” Fordham Law Review. 77(5):2087-2141.

- Wheeler, David A. (May 8, 2014). “Why Open Source Software/Free Software (OSS/FS, or FOSS)? Look at the numbers!” dwheeler.com. Retrieved 2022-01-07.

- See Wikipedia. ↵

- See Open Content Definition. ↵

denoting software for which the original source code is made freely available and may be redistributed and modified.

A code Snippet is a programming term that refers to a small portion of re-usable source code, machine code, or text. Snippets help programmers reduce the time it takes to type in repetitive information while coding. Code Snippets are a feature on most text editors, code editors, and IDEs.

Source code is generally understood to mean programming statements that are created by a programmer with a text editor or a visual programming tool and then saved in a file.

A licence is a document that specifies what can and cannot be done with a work (whether sound, text, image or multimedia). It grants permissions and states restrictions. Broadly speaking, an open licence is one which grants permission to access, re-use and redistribute a work with few or no restrictions. (A full set of conditions which must be met in order for a licence to be open is available in the Open Knowledge Definition 1.0.). For example, a piece of writing on a website made available under an open licence would be free for anyone to: print out and share, publish on another website or in print, make alterations or additions, incorporate, in part or in whole, into another piece of writing, use as the basis for a work in another medium – such as an audio recording or a film, and do many other things …

Openly licensed works are hence free to be shared, improved and built upon! The exact permissions granted depend on the full text of the open license that is applied.

Free educational materials that are openly licensed to enable reuse and redistribution by users.

a mixture or fusion of disparate elements.

"the movie becomes a weird mash-up of 1950s western and 1970s TV cop show"

a recording created by digitally combining and synchronizing instrumental tracks with vocal tracks from two or more different songs.

"a classic dancefloor mash-up"

Computing

a web page or application created by combining data or functionality from different sources.

"a mash-up that mixes CNN news with links to Wikipedia articles"

A Creative Commons (CC) license is one of several public copyright licenses that enable the free distribution of an otherwise copyrighted "work". A CC license is used when an author wants to give other people the right to share, use, and build upon a work that the author has created. CC provides an author flexibility (for example, they might choose to allow only non-commercial uses of a given work) and protects the people who use or redistribute an author's work from concerns of copyright infringement as long as they abide by the conditions that are specified in the license by which the author distributes the work.

The ALMS Framework provides a way of thinking about those technical choices and understanding the degree to which they enable or impede a user's ability to engage in the 5R activities permitted by open licenses.