Influences on Parenting

Diana Lang and Marissa Diener

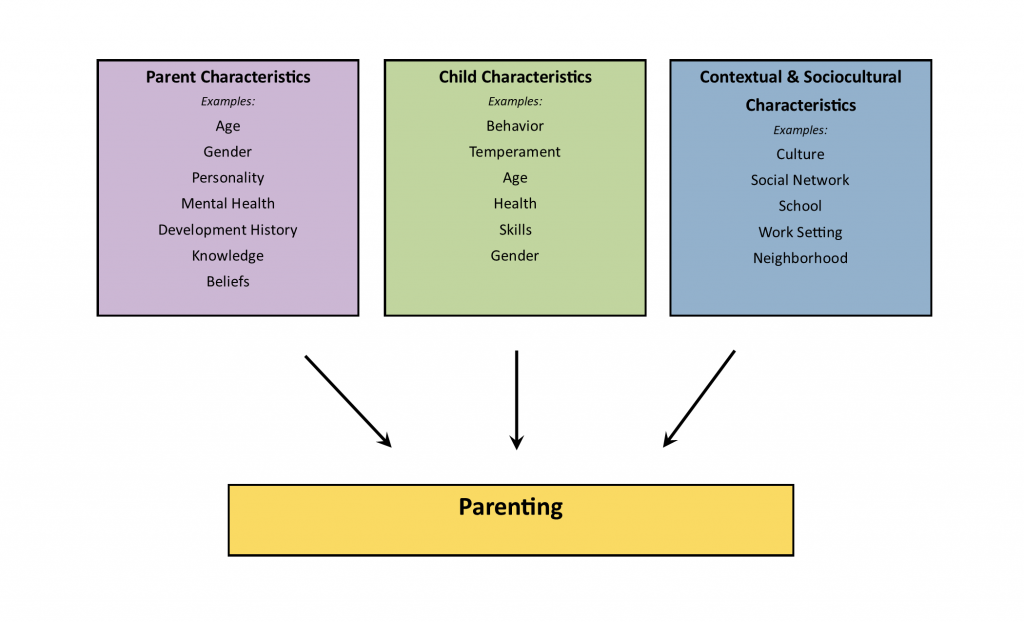

Parenting is a complex process in which parents and children both impact one another. There are many reasons that parents behave the way they do. The multiple influences on parenting are still being explored. Proposed influences on parental behavior include:

- parent characteristics,

- child characteristics, and

- contextual and sociocultural characteristics.[1] [2]

Parent Characteristics

Parents bring unique traits and qualities to the parenting relationship that affect their decisions as parents. These characteristics include a parent’s age, gender identity, personality, developmental history, beliefs, knowledge about parenting and child development, and mental and physical health. Parents’ personalities also affect parenting behaviors. Parents who are more agreeable, conscientious, and outgoing are warmer and provide more structure to their children. Parents who are more agreeable, less anxious, and less negative also support their children’s autonomy more than parents who are anxious and less agreeable.[3] Parents who have these personality traits appear to be better able to respond to their children positively and provide a more consistent, structured environment for their children.

Parents’ developmental histories, or their experiences as children, can also affect their parenting strategies. Parents may learn parenting practices from their own parents. Fathers whose own parents provided monitoring, consistent and age-appropriate discipline, and warmth are more likely to provide this constructive parenting to their own children.[4] Patterns of negative parenting and ineffective discipline also appear from one generation to the next. However, parents who are dissatisfied with their primary caregivers’ approach may be more likely to change their parenting methods when they have children.

Child Characteristics

Parenting is bidirectional. Not only do parents affect their children, but children influence their parents as well.[5] Child characteristics, such as gender identity, birth order, temperament, and health status, can affect parenting behaviors and roles. For example, an infant with an easy temperament may enable parents to feel more effective, as they are easily able to soothe the child and elicit smiling and cooing. On the other hand, a cranky or fussy infant can elicit fewer positive reactions from parents and may result in parents feeling less effective in the parenting role.[6] Over time, parents of more difficult children may become more punitive and less patient with their children.[7] [8] Parents who have a fussy, difficult child tend to be less satisfied with their marriages and have greater challenges in balancing work and family roles.[9] Thus, child temperament is one of the child characteristics that influences how parents behave with their children.

Another child characteristic is the child’s gender identity. Some parents assign different household chores to their children based on their child’s gender identity. For example, older research has shown girls are more often responsible for caring for younger siblings and household chores, whereas boys are more likely to be asked to perform chores outside the home, such as mowing the lawn.[10] Research has also demonstrated that some parents talk differently with their children based on their child’s gender identity, such as providing more scientific explanations to their sons and using more emotion words with their daughters.[11]

Contextual Factors and Sociocultural Characteristics

The parent-child relationship does not occur in isolation. Sociocultural characteristics, including economic hardship, religion, politics, neighborhoods, schools, and social support, can also influence parenting. Parents who experience economic hardship tend to be more easily frustrated, depressed, and sad, and these emotional characteristics can affect their parenting skills.[12] Culture can also impact parenting behaviors in fundamental ways. Although promoting the development of skills necessary to function effectively in one’s community, to the best of one’s abilities, is a universal goal of parenting, the specific skills necessary vary widely from culture to culture. Thus, parents have different goals for their children that partially depend on their culture.[13] For example, parents vary in how much they emphasize goals for independence and individual achievements and goals involving maintaining harmonious relationships and being embedded in a strong network of social relationships.

These differences in parental goals can also be influenced by culture and immigration status. Other important contextual characteristics, such as the neighborhood, school, and social networks, can affect parenting, even though these settings do not always include both the child and the parent.[14] For example, Latina mothers who perceived their neighborhood as more dangerous showed less warmth with their children, perhaps because of the greater stress associated with living in a threatening environment.[15]

Summary: Many Factors Can Influence Parenting and Child Outcomes

Parenting factors include characteristics of the primary caregiver, such as gender identity and personality, as well as characteristics of the child, such as age and temperament. Parenting styles provide reliable indicators of parenting functioning that predicts child well-being across a wide spectrum of environments and diverse communities. Caregivers who consistently engage in high responsiveness and appropriate demandingness with children are linked to more “quality” outcomes for youth.

The interaction among all these factors creates many different patterns of parenting behaviors. For instance, parenting influences a child’s development as well as the development of the parent or primary caregiver. And, as parents face new challenges, they change their parenting strategies and construct new aspects of their identities. Furthermore, the goals and tasks of parents may change over time as their children develop.[16] [17] However, the next page outlines typical parenting tasks, roles, goals, and responsibilities that extend across cultures and time.

- Belsky, J. (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83-96. ↵

- Demick, J. (1999). Parental development: Problem, theory, method, and practice. In Mosher, R. L., Youngman D. J., & Day J. M. (Eds.), Human development across the life span: Educational and psychological applications (pp. 177-199). Praeger. ↵

- Prinzie, P., Stams, G. J., Dekovic, M., Reijntjes, A. H., & Belsky, J. (2009). The relations between parents’ Big Five personality factors and parenting: A meta-review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(1), 351–362. ↵

- Kerr, D. C. R., Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., & Owen, L. D. (2009). A prospective three generational study of fathers’ constructive parenting: Influences from family of origin, adolescent adjustment, and offspring temperament. Developmental Psychology, 45(1), 1257-1275. ↵

- Child Characteristics is adapted from "The Developing Parent" by Marisa Diener, licensed CC BY NC SA. ↵

- Eisenberg, N., Hofer, C., Spinrad, T., Gershoff, E., Valiente, C., Losoya, S. L., Zhou, Q., Cumberland, A., Liew, J., Reiser, M., & Maxon, E. (2008). Understanding parent-adolescent conflict discussions: Concurrent and across-time prediction from youths’ dispositions and parenting. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 73(2), 1-160. ↵

- Clark, L. A., Kochanska, G., & Ready, R. (2000). Mothers’ personality and its interaction with child temperament as predictors of parenting behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 274-285. ↵

- Kiff, C. J., Lengua, L. J., & Zalewski, M. (2011). Nature and nurturing: Parenting in the context of child temperament. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 251–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567011-0093-4 ↵

- Hyde, J. S., Else-Quest, N. M., Goldsmith, H. H., & Biesanz, J. C. (2004). Children's temperament and behavior problems predict their employed mothers' work functioning. Child Development, 75(2), 580-594. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00694.x ↵

- Grusec, J. E., Goodnow, J. J., & Cohen, L. (1996). Household work and the development of concern for others. Developmental Psychology, 32(6), 999-1007. ↵

- Crowley, K., Callanan, M. A., Tenenbaum, H. R., & Allen, E. (2001). Parents explain more often to boys than to girls during shared scientific thinking. Psychological Science, 12(3), 258-261. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.00347 ↵

- Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2004). Resilience in Midwestern families: Selected findings from the first decade of a prospective, longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64(2): 361-373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00361.x ↵

- Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. (2007). Parents' goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17(1), 183-209. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00419.x ↵

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. Annals of Child Development, 6(1), 187-249. ↵

- Gonzalez-Backen, M. A., Updegraff, K. A., & Umaña-Taylor, A. J. (2011). Mexican-origin adolescent mothers’ stressors and psychosocial functioning: Examining ethnic identity affirmation and familism as moderators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40(2), 140-157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9511-z ↵

- Baumrind, D. (1991). The influence of parenting style on adolescent competence and substance use. Journal of Early Adolescence, 11, 56–95. 10.1177/0272431691111004 ↵

- Barber, B. K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296-3319. doi:10.2307/1131780 ↵